Recovery Legislation Provides Historic Opportunity to Advance Racial Equity

End Notes

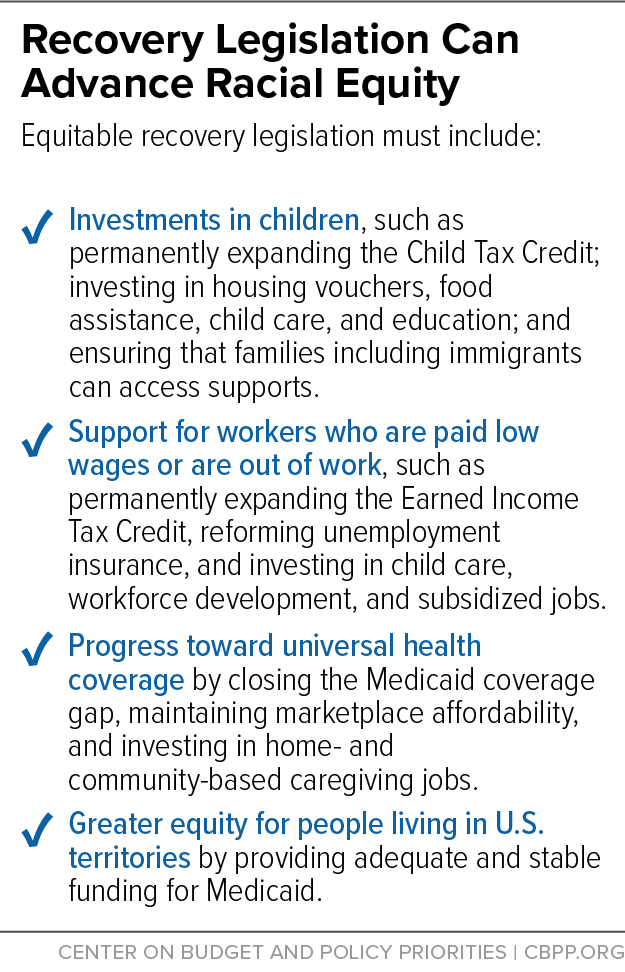

[1] For more details on why building an equitable recovery requires investing in these three areas, see Sharon Parrott et al., “Building an Equitable Recovery Requires Investing in Children, Supporting Workers, and Expanding Health Coverage,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 24, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/building-an-equitable-recovery-requires-investing-in-children.

[2] According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey public use microdata sample, the poverty rate for people who identify as American Indian and Alaska Native alone or in combination, regardless of Latino ethnicity, was 20.4 percent. By comparison, the poverty rate for people who identify as Black only and not Latino was 21.1 percent.

[3] Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo, “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians,” Pew Research Center, July 12, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/; AAPI Data, “Poverty by Detailed Group (National),” http://aapidata.com/stats/national/national-poverty-aa-aj/.

[4] Asian Americans Advancing Justice, “A Community of Contrasts: Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the West,” 2015, https://www.advancingjustice-la.org/sites/default/files/A_Community_of_Contrasts_AANHPI_West_2015.pdf.

[5] CBPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey public use microdata sample.

[6] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, National Academies Press, 2019, https://www.nap.edu/read/25246.

[7] Arloc Sherman and Tazra Mitchell, “Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long Term, Many Studies Find,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-succeed-over.

[8] Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Economic Security Programs Reduce Overall Poverty, Racial and Ethnic Inequities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 28, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-reduce-overall-poverty-racial-and-ethnic.

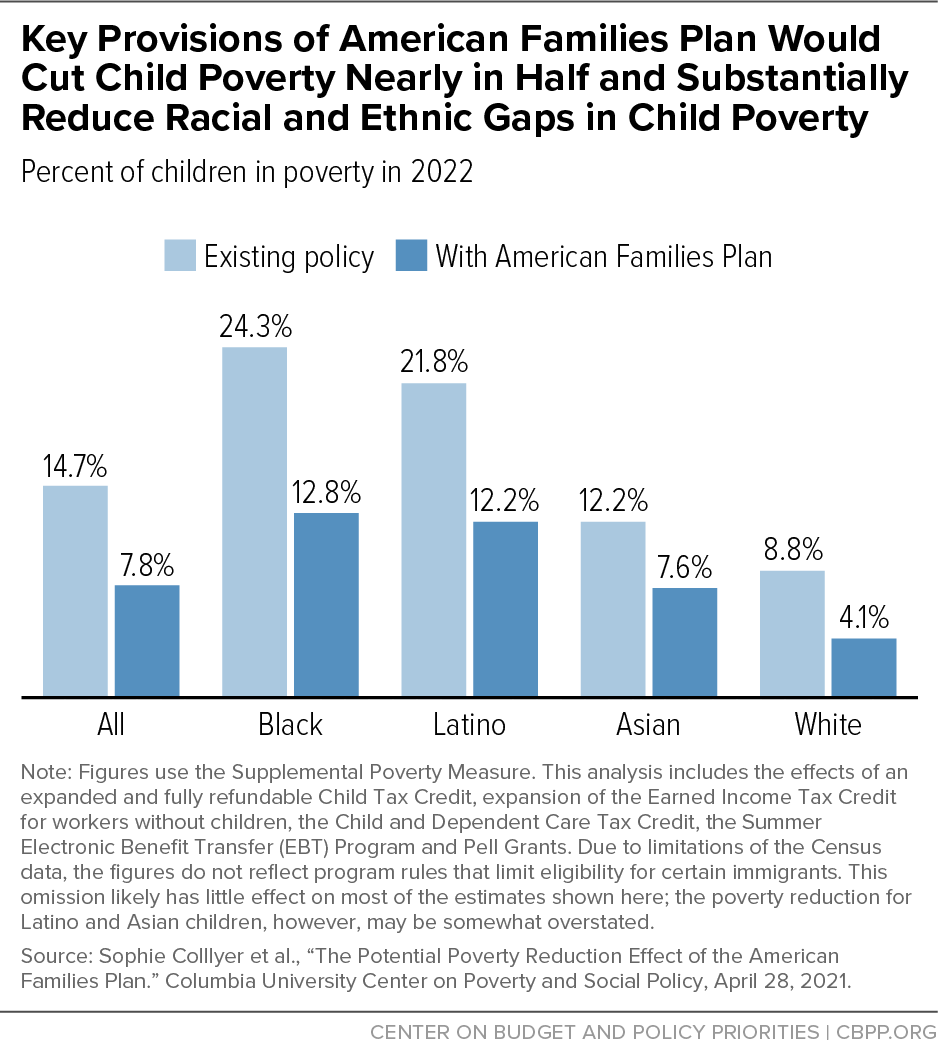

[9] Sophie Collyer et al., “The Potential Poverty Reduction Effect of the American Families Plan,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, April 28, 2021, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/6089abfe510bad33dcecc4c9/1619635200067/Poverty-Reduction-Analysis-American-Families-Plan-CPSP-2021.pdf. Due to limitations of the Census data, the figures do not reflect program rules that limit eligibility for the Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, SNAP, and other benefits for certain immigrants. This omission likely has little effect on most of the estimates shown here; the poverty reduction for Latino and Asian children, however, may be somewhat overstated.

[10] Arthur J. Rolnick and Rob Grunewald, “Early Childhood Development: Economic Development with a High Public Return,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, March 1, 2003, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2003/early-childhood-development-economic-development-with-a-high-public-return.

[11] Cortney Sanders, “Research Note: Combining Early Education and K-12 Investments Has Powerful Positive Effects,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 28, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/research-note-combining-early-education-and-k-12-investments-has.

[12] Jacob Goldin and Katherine Michelmore, “Who Benefits From the Child Tax Credit?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 27940, October 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27940.

[13] About a quarter of rural residents identify as Black, Latino, Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander, or identify with more than one race. Chuck Marr et al., “Expanding Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit Would Benefit More Than 10 Million Rural Residents, Strongly Help Rural Areas,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 6, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/expanding-child-tax-credit-and-earned-income-tax-credit-would-benefit-more.

[14] Figures for children identified as American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) are particularly sensitive to how the racial category is defined. Among the roughly 1.6 million children identified as AIAN alone or in combination, regardless of Latino ethnicity, 124,000 would be lifted above the poverty line by a permanent Child Tax Credit expansion and about 1.5 million would benefit from the expansion in total. (If we apply the non-overlapping categories this report uses for other groups, only 555,000 children are considered AIAN alone, not Latino; 50,000 of them would be lifted above the poverty line by this Child Tax Credit expansion and about 524,000 would benefit from this expansion in total.) CBPP analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2019 Current Population Survey (for national total) allocated by race or ethnicity based on CBPP analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) data for 2016-2018, using 2021 tax parameters and incomes adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars. These calculations use the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which counts more forms of income than the “official” poverty measure (among other differences). Chuck Marr et al., “Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 24, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/congress-should-adopt-american-families-plans-permanent-expansions-of-child.

[15] Sonya Acosta, “Rental Assistance in Recovery Legislation Needed to Protect Children From Hardship and Help Build a More Equitable Future,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 26, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/rental-assistance-in-recovery-legislation-needed-to-protect-children-from-hardship-and-help.

[16] Michele Wood, Jennifer Turnham, and Gregory Mills, “Housing Affordability and Family Well-Being: Results from the Housing Voucher Evaluation,” Housing Policy Debate, Vol. 19, No. 2, January 2008, pp. 367-412.

[17] Will Fischer, Sonya Acosta, and Erik Gartland, “More Housing Vouchers: Most Important Step to Help More People Afford Stable Homes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated May 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/more-housing-vouchers-most-important-step-to-help-more-people-afford-stable-homes.

[18] Sophie Collyer et al., “Housing Vouchers and Tax Credits: Pairing the Proposal to Transform Section 8 with Expansions to the EITC and Child Tax Credit Could Cut the National Poverty Rate by Half,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, October 7, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/5f7dd00e12dfe51e169a7e83/1602080783936/Housing-Vouchers-Proposal-Poverty-Impacts-CPSP-2020.pdf.

[19] Alicia Mazzara, “Expanding Housing Vouchers Would Cut Poverty and Reduce Racial Disparities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 11, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/expanding-housing-vouchers-would-cut-poverty-and-reduce-racial-disparities.

[20] Christine Johnson-Staub, “Equity Starts Early: Addressing Racial Inequities in Child Care and Early Education Policy,” Center for Law and Social Policy, December 2017, https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2017/12/2017_EquityStartsEarly_0.pdf.

[21] Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “The Long-Term Effects of Universal Preschool in Boston,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 28756, May 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w28756.

[22] Caitlin McLean et al. “Early Childhood Workforce Index 2020,” Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, 2021, https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2020/.

[23] Brynne Keith-Jennings, Catlin Nchako, and Joseph Llobrera, “Number of Families Struggling to Afford Food Rose Steeply in Pandemic and Remains High, Especially Among Children and Households of Color,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/number-of-families-struggling-to-afford-food-rose-steeply-in-pandemic-and.

[24] Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2019,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, September 2020, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=99281.

[25] Keith-Jennings, Nchako, and Llobrera, op. cit.

[26] CBPP analysis of Census Bureau’s March 2020 Current Population Survey (accessed via IPUMS-CPS).

[27] CBPP analysis of March 2020 Current Population Survey using the Supplemental Poverty Measure.

[28] CBPP estimates based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2019 Current Population Survey, using 2021 tax parameters and incomes adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars. The estimates count all workers aged 19 to 65 (excluding full-time students aged 19 to 23) who are pushed below the Census poverty thresholds — or further below them — by their federal income tax liability (if any) and the employee share of the payroll tax. The estimate excludes full-time students aged 19 to 23 because, under current law, their parents can claim them as qualifying children for the larger EITC for families with children. Poverty status is determined at the level of the tax filing unit. We use the 2020 Census official poverty threshold that is appropriate for the tax unit based on the number and age of the tax unit members, inflated to 2021 dollars.

[29] Among the roughly 1.4 million workers aged 19 and over without children (excluding students under age 24 attending school at least part time) who identify as AIAN alone or in combination, regardless of Latino ethnicity, 365,000 would benefit from the EITC expansion in the American Families Plan. (If we apply the non-overlapping categories that this report uses for other groups, only 530,000 workers aged 19 and over without children, excluding students under age 24 attending school at least part time, identify as AIAN alone, not Latino; 140,000 of them would benefit from the Families Plan’s EITC expansion.) CBPP analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2019 Current Population Survey (for national total) allocated by race or ethnicity based on CBPP analysis of ACS data for 2016-2018, using 2021 tax parameters and incomes adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars. Marr et al., “Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent,” op. cit.

[30] Austin Nichols and Margaret Simms, “Racial and Ethnic Differences in Receipt of Unemployment Insurance Benefits during the Great Recession,” Urban Institute, June 2012, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/25541/412596-Racial-and-Ethnic-Differences-in-Receipt-of-Unemployment-Insurance-Benefits-During-the-Great-Recession.PDF.

[31] Nzingha Hooker and Alexa Tapia, “Slashing Unemployment Benefit Weeks Based on Jobless Rates Hurts Workers of Color,” National Employment Law Project, May 14, 2021, https://www.nelp.org/publication/slashing-unemployment-benefit-weeks-on-jobless-rates-hurts-workers-of-color.

[32] Chad Stone, “Congress Should Heed President Biden’s Call for Fundamental UI Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 5, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/congress-should-heed-president-bidens-call-for-fundamental-ui-reform

[33] Joseph Zeballos-Roig and Juliana Kaplan, “GOP-led states are cutting $300 weekly federal unemployment benefits. Here are the 24 states making the cut this summer,” Business Insider, May 25, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/republican-states-cutting-unemployment-benefits-expanded-300-weekly-biden-stimulus-2021-5.

[34] Maura Baldiga et al., “Data-for-Equity Research Brief: Child Care Affordability for Working Parents,” diversitydatakids, November 2018, https://www.diversitydatakids.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/child-care_update.pdf; Rasheed Malik et al., ”America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018,” Center for American Progress, December 6, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2018/12/06/461643/americas-child-care-deserts-2018/.

[35] Rebecca Ullrich, Stephanie Schmit, and Ruth Cosse, “Inequitable Access to Child Care Subsidies,” Center for Law and Social Policy, April 2019, https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/04/2019_inequitableaccess.pdf.

[36] Joseph Llobrera, Catlin Nchako, and Lauren Hall, “SNAP Restricts Nutrition Assistance for Low-Income Non-Elderly Adults Not Living With Minor Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 28, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-frayed-and-fragmented-system-of-supports-for-low-income-adults#SNAP.

[37] LaDonna Pavetti, “TANF Studies Show Work Requirement Proposals for Other Programs Would Harm Millions, Do Little to Increase Work,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 13, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-studies-show-work-requirement-proposals-for-other-programs

[38] Erin Brantley, Drishti Pillai, and Leighton Ku, “Association of Work Requirements with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation by Race/Ethnicity and Disability Status, 2013-2017,” JAMA Network Open, June 26, 2020, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2767673.

[39] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Federal Rental Assistance Fact Sheets,” updated June 1, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/federal-rental-assistance-fact-sheets#US.

[40] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Federal Rental Assistance,” updated November 15, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/federal-rental-assistance.

[41] Meghan Henry et al., “The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, January 2021, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

[42] Will Fischer, Sonya Acosta, and Anna Bailey, “An Agenda for the Future of Public Housing,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 11, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/an-agenda-for-the-future-of-public-housing.

[43] Laura Meyer, “Subsidized Employment: A Proven Strategy to Aid an Equitable Economic Recovery,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated April 1, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/subsidized-employment-a-proven-strategy-to-aid-an-equitable-economic.

[44] Chad Stone, “Robust Unemployment Insurance, Other Relief Needed to Mitigate Racial and Ethnic Unemployment Disparities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 5, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/robust-unemployment-insurance-other-relief-needed-to-mitigate-racial-and-ethnic.

[45] For additional details on subsidized jobs, see Caitlin C. Schnur, Chris Warland, and Melissa Young, “Framework for an Equity-Centered National Subsidized Employment Program,” Heartland Alliance, January 12, 2021, https://nationalinitiatives.issuelab.org/resource/framework-for-an-equity-centered-national-subsidized-employment-program.html. For additional details on training and career navigation, see Larry Good and Earl Buford, “Modernizing and Investing in Workforce Development,” Corporation for a Skilled Workforce, March 2021, https://skilledwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Modernizing-and-Investing-in-Workforce-Development.pdf.

[46] Laura Meyer and LaDonna Pavetti, ”TANF Improvements Needed to Help Parents Find Better Work and Benefit From an Equitable Recovery,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 28, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-improvements-needed-to-help-parents-find-better-work-and.

[47] Johanna Lacoe et al., “Supporting Reentry Employment and Success: A Summary of the Evidence for Adults and Young Adults,” Mathematica, September 2019, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/REOSupportingReentryEmploymentRB090319.pdf.

[48] Pronita Gupta et al., “Paid Family and Medical Leave is Critical for Low-wage Workers and Their Families,” Center for Law and Social Policy, December 19, 2018, https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact-sheet/paid-family-and-medical-leave-critical-low-wage-workers-and-their-families.

[49] Kathleen Romig and Kathleen Bryant, “A National Paid Leave Program Would Help Workers, Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/a-national-paid-leave-program-would-help-workers-families.

[50] Robin A. Cohen et al., “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2018,” National Center for Health Statistics, May 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201905.pdf.

[51] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Chart Book: Accomplishments of Affordable Care Act,” March 19, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/chart-book-accomplishments-of-affordable-care-act; Jacob Goldin, Ithai Z. Lurie, and Janet McCubbin, “Health Insurance and Mortality: Experimental Evidence from Taxpayer Outreach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 2021, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/136/1/1/5911132.

[52] Jesse C. Baumgartner et al., “How the Affordable Care Act Has Narrowed Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Health Care,” Commonwealth Fund, January 16, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/jan/how-ACA-narrowed-racial-ethnic-disparities-access.

[53] Jennifer Tolbert, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 6, 2020, https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

[54] See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity,” updated May 26, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html; and Kaiser Family Foundation “COVID-19 Deaths by Race/Ethnicity,” https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/covid-19-deaths-by-race-ethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[55] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Employer-Sponsored Coverage Rates for the Nonelderly by Race/Ethnicity,” accessed May 2021, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/nonelderly-employer-coverage-rate-by-raceethnicity/.

[56] Judith Solomon, “Federal Action Needed to Close Medicaid ‘Coverage Gap,’ Extend Coverage to 2.2 Million People,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 6, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/federal-action-needed-to-close-medicaid-coverage-gap-extend-coverage-to-22-million.

[57] Tara Straw et al., “Health Provisions in American Rescue Plan Act Improve Access to Health Coverage During COVID Crisis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 11, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/health-provisions-in-american-rescue-plan-act-improve-access-to-health-coverage.

[58] Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 21, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/.

[59] Jennifer Wagner and Judith Solomon, “Continuous Eligibility Keeps People Insured and Reduces Costs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/continuous-eligibility-keeps-people-insured-and-reduces-costs.

[60] Sarah Lueck and Tara Straw, “Recovery Legislation Should Build on ACA Successes to Expand Health Coverage, Improve Affordability,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 8, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/recovery-legislation-should-build-on-aca-successes-to-expand-health-coverage.

[61] Daniel McDermott and Cynthia Cox, “A Closer Look at the Uninsured Marketplace Eligible Population Following the American Rescue Plan Act,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 27, 2021, https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/a-closer-look-at-the-uninsured-marketplace-eligible-population-following-the-american-rescue-plan-act/.

[62] Sarah Lueck, “Recovery Legislation Should Reduce Marketplace Deductibles, Other Cost Sharing,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 19, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/recovery-legislation-should-reduce-marketplace-deductibles-other-cost-sharing.

[63] Tara Straw, “Trapped by the Firewall: Policy Changes Are Needed to Improve Health Coverage for Low-Income Workers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 3, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/trapped-by-the-firewall-policy-changes-are-needed-to-improve-health-coverage-for.

[64] Anna Bailey, “An Equitable Recovery Needs Investments in Connecting People Leaving Jail or Prison to Health Care,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 14, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/an-equitable-recovery-needs-investments-in-connecting-people-leaving-jail-or-prison-to-health.

[65] Heidi Hartmann et al., “The Shifting Supply and Demand of Care Work: The Growing Role of People of Color and Immigrants,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, June 2018, https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/C470_Shifting-Supply-of-Care-Work-Immigrants-and-POC.pdf.

[66] Chye-Ching Huang, “Fundamentally Flawed 2017 Tax Law Largely Leaves Low- and Moderate-Income Americans Behind,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 27, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/fundamentally-flawed-2017-tax-law-largely-leaves-low-and-moderate-income.

[67] Roderick Taylor, “ITEP-Prosperity Now: 2017 Tax Law Gives White Households in Top 1% More Than All Races in Bottom 60%,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 11, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/itep-prosperity-now-2017-tax-law-gives-white-households-in-top-1-more-than-all-races-in-bottom.

[68] Chuck Marr et al., “Biden Proposals Would Reduce Large Tax Advantages for Those at the Top, Address Tax Gap,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 11, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/biden-proposals-would-reduce-large-tax-advantages-for-those-at-the-top-address.

[69] Chuck Marr et al., “Asking Wealthiest Households to Pay Fairer Amount in Tax Would Help Fund a More Equitable Recovery,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 22, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/asking-wealthiest-households-to-pay-fairer-amount-in-tax-would-help-fund-a.