Our success as a nation depends on whether all people, regardless of race or ethnicity, have the opportunity to thrive. Economic security programs such as Social Security, food assistance, tax credits, and housing assistance can help provide opportunity by ameliorating short-term poverty and hardship and, by doing so, improving children’s long-term outcomes. Over the last half-century, these assistance programs have reduced poverty for millions of people — including children, who are highly susceptible to poverty’s ill effects.

At the same time, barriers to opportunity, including discrimination and disparities in access to employment, education, and health care, remain enormous and keep poverty rates much higher for some racial and ethnic groups than others. While government programs have done much to narrow these disparities in poverty, further progress will require stronger government efforts to reduce poverty and discrimination and build opportunity for all.

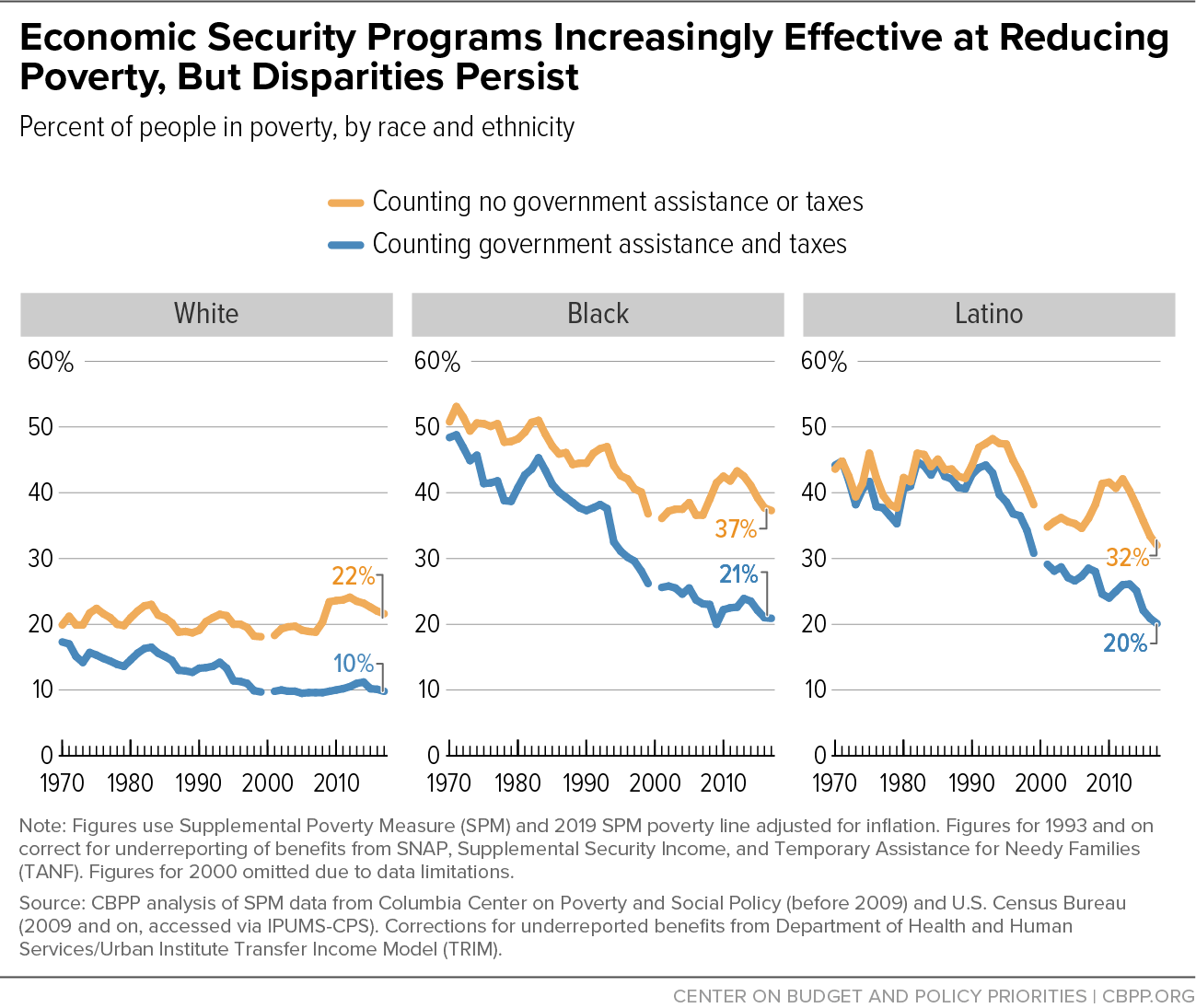

Between 1970 and 2017 the poverty rate fell for all groups, but it fell even more for Black and Latino people: by 27 and 24 percentage points, respectively, compared to 8 percentage points for white non-Latino people, we calculate.[1] Even with this reduction, poverty rates for Black and Latino people remained far above the white poverty rate.[2] Our series begins in 1970, the first year that data on Latino ethnicity are available, and ends in 2017, the latest year that data on underreporting of key government benefits are available. (Rather than the official poverty measure, this report uses a variant of the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which among other advantages incorporates the value of non-cash and tax-based benefits, as we detail below.)

Economic security programs have become more effective at reducing poverty and racial disparities over the last five decades. In 1970, families’ government benefits and the taxes they paid lowered the white poverty rate by 3 percentage points and the Black poverty rate by 2 percentage points, and left the Latino poverty rate unchanged. In contrast, in 2017, accounting for government benefits and taxes lowered the white poverty rate by 12 percentage points, Black poverty by 16 percentage points, and Latino poverty by 12 percentage points. (See Figure 1.)

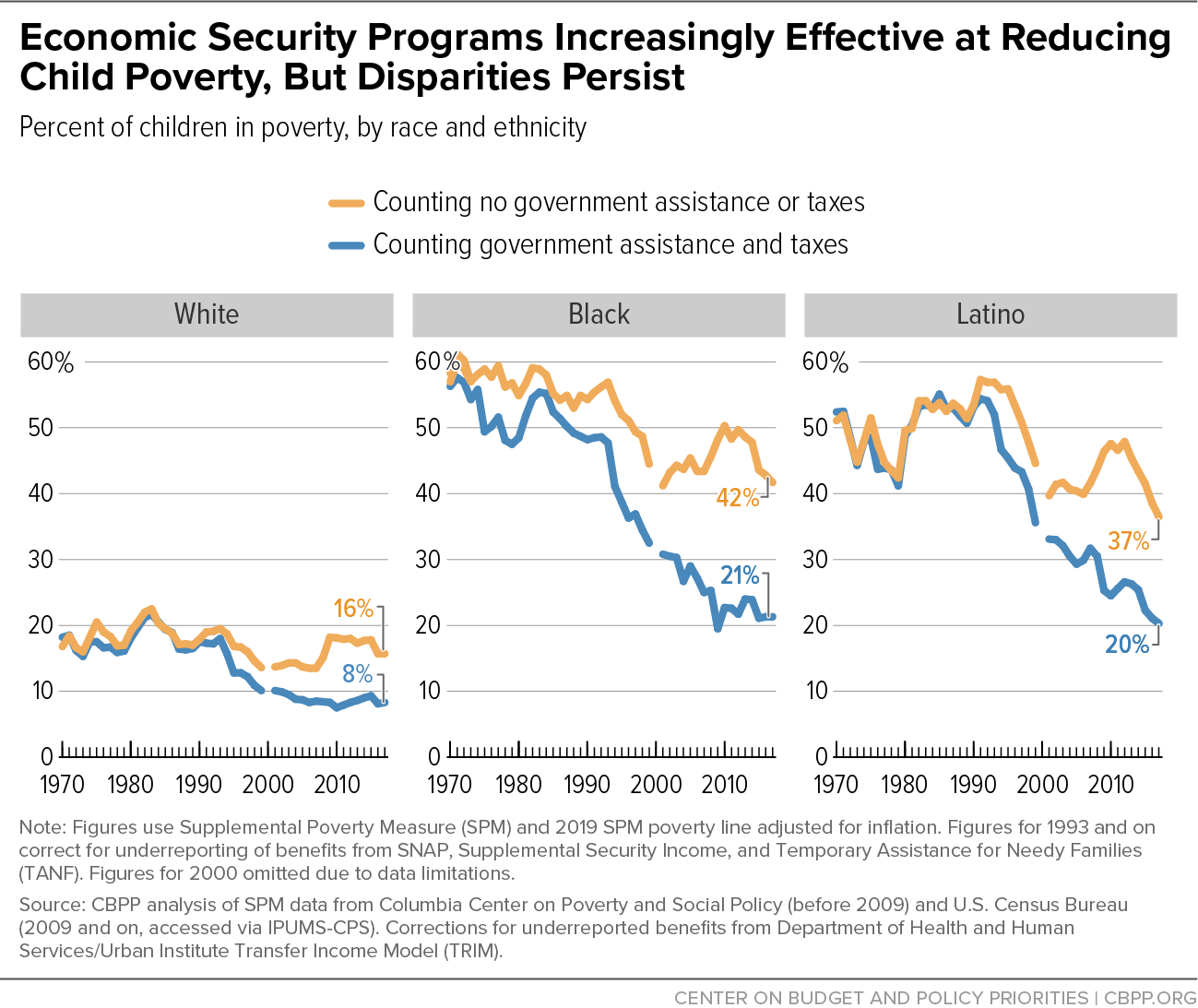

For children, government programs played an even larger role in lowering poverty and narrowing racial and ethnic disparities. Between 1970 and 2017, the Black child poverty rate fell by 35 percentage points, the Latino child poverty rate by 32 percentage points, and the white child poverty rate by 10 percentage points (but, again, poverty remains far lower among white children than Black and Latino children). More than half of these declines were driven by the increasing poverty-reducing effectiveness of government assistance at lifting families’ incomes above the poverty line. (See Figure 2.)

Moreover, many studies have found that assistance programs like nutrition aid and health coverage improve children’s long-term trajectories; some of the poverty reduction stemming from, for example, improved educational attainment is due to investments in nutrition and health care years earlier when adults were children.[3]

Despite this progress, past and present discrimination in both private markets and public policies left poverty rates in 2017 more than twice as high among Black (20.9 percent) and Latino (20.1 percent) people than among white people (9.8 percent). Child poverty reflected the same dynamic, with Black and Latino child poverty rates at 21.3 and 20.3 percent, respectively, compared to 8.3 percent among white children.

Even in the relatively strong pre-pandemic economy, many households struggled to afford rent and other necessities.[4] In 2016, 1 in 3 Black (33 percent) and Latino (34 percent) workers earned below-poverty wages,[5] as did nearly 1 in 5 white workers (19 percent), according to the Economic Policy Institute.[6] These figures are not much lower than they were in 1973 (38 percent for Black, 37 percent for Latino, and 23 percent for white workers).

What’s more, the economy of 2017 bears little resemblance to today’s, and early evidence suggests that the pandemic and downturn have worsened longstanding economic disparities by race and ethnicity. Jobs in low-paying industries — disproportionately held by people of color — were down more than twice as much between February and December 2020 as jobs in medium-wage industries and nearly four times as much as in high-wage industries.[7] Women of color have experienced especially sharp losses.[8]

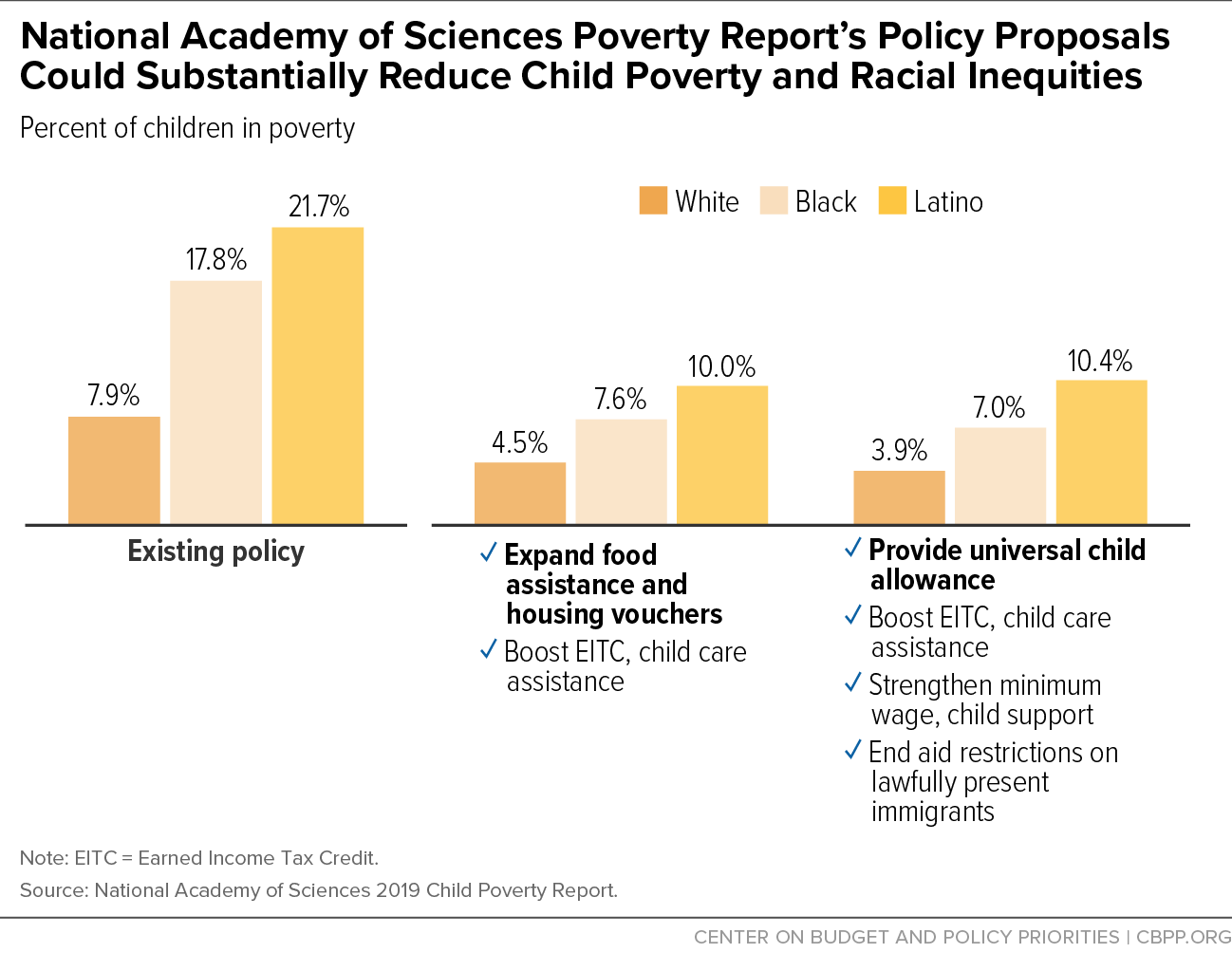

Policymakers could make substantial progress in reducing the gaping racial disparities in poverty and access to opportunity by expanding the scope and reach of effective policies, such as housing vouchers, tax credits, and food assistance. The Biden Administration’s emergency relief proposal could cut child poverty in half and cut Black and Latino poverty by a third.[9] Two policy packages that a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) panel recently evaluated would cut in half both the child poverty rate and the gap in poverty rates between white children and Black and Latino children.[10] A proposal to make housing vouchers available to all eligible families put forward by President Biden during his campaign would reduce the white-Black poverty gap by up to a third and the white-Latino poverty gap by up to half. That proposal, combined with two tax credit proposals that Vice President Kamala Harris endorsed during the campaign, would reduce racial and ethnic poverty gaps by even more.[11]

Many other wealthy nations such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Nordic countries have similar (or even higher) poverty rates than the United States before factoring in the impact of economic security programs. But these countries have lower poverty rates — sometimes much lower — after counting benefits from government programs because they have stronger policies to shore up incomes of households that don’t earn enough to make ends meet.[12] The United States can well afford to adopt stronger policies to lower poverty both overall and for children.

To provide a full picture of the public income support system for low-income families, this analysis blends the Supplemental Poverty Measure or SPM — which counts more forms of income than the “official” poverty measure (among other differences) and therefore more accurately reflects the resources available to low-income households — with corrections for underreporting of key government benefits in survey data.[13]

The SPM counts income from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), rental subsidies, and other federal non-cash benefits and refundable tax credits, which the official poverty measure omits. The SPM also subtracts federal and state income taxes,[14] federal payroll taxes, and certain expenses (such as child care and out-of-pocket medical expenses) from income when calculating a family’s available income for basics such as food, clothing, and shelter. A family is considered to be in poverty if its resources are below a poverty threshold that accounts for differences in family composition and geographic differences in housing costs.

We created a poverty series merging data files from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) with historical SPM data produced by the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy[15] and corrections for underreporting created by the Urban Institute. We use the Census Bureau’s SPM data for 2009 through 2017, and the Columbia SPM data for prior years. Our poverty series uses the 2019 SPM poverty line, adjusted in prior years for inflation.[16] In 2019, the SPM poverty threshold for a two-adult, two-child family renting in an average-cost community was $28,881.

Our analysis focuses chiefly on white, Black, and Latino people because data for other racial groups are not available for all years. (For example, Asian trends only become available in 2002.) The limited size of our survey sample also complicates the task of drawing reliable conclusions about smaller populations, including the Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) populations. Nonetheless, recent data make clear that poverty rates are extremely high for the AIAN population, similar to the Black population.[17] In addition, while Asian poverty rates overall resemble white poverty rates, the Asian community is particularly diverse. A 2015 report by Asian Americans Advancing Justice notes that “lower poverty rates among Asian Americans as a racial group cause many to overlook higher poverty rates among Southeast Asian Americans as distinct ethnic groups.”[18]

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Poverty Reflect Discriminatory Policies and Practices

Economic security programs have become increasingly effective at reducing poverty for all major racial and ethnic groups.[19] (See Figure 1.) Still, our data reveal strong racial and ethnic disparities in income both before and after counting government assistance and taxes. These racial and ethnic disparities in poverty reflect historical and ongoing discrimination, public and private, that has limited opportunity in many ways including in the areas of housing, education, and employment.

In our analysis, “pre-government” income includes a family’s earnings and other forms of private income, such as interest, dividends, and child support, and subtracts certain non-discretionary expenses like child care and medical out-of-pocket costs. Pre-government income does not include government benefits, such as Social Security or SNAP, or account for taxes paid (or tax credits received).

For all years of data in our series from 1970-2017, Black and Latino people have been more likely to live in families with pre-government income below the SPM poverty line than white people. In our latest year of data, the SPM pre-government poverty rates for Black and Latino people were 37.3 percent and 32.0 percent, respectively, compared to 21.6 percent for white people. Put another way, Black and Latino people were 1.7 and 1.5 times more likely to have pre-government income below the SPM poverty line than white people.

The economic barriers imposed by past and present racism and systemic bias in housing, education, and the criminal justice system are well documented, with much of the impact originating from biased government policies. Through much of the 20th century, the federal government explicitly excluded Black people from opportunities to secure affordable housing, including government-backed mortgages, subsidized housing developments, and early public housing.[20] By reserving these housing opportunities for white people and confining Black people to disadvantaged areas, the federal government fostered inequities not just in homeownership and wealth, but in education, as inadequate tax revenues from low property values and other sources of underinvestment hampered schools’ quality.[21]

Discriminatory policies and practices in the criminal justice system have fueled the disproportionate mass incarceration of people of color, even when people of color and white people commit crime at similar rates.[22] Mass incarceration of adults and youth takes a deep toll on families, who lose loved ones, parents, and breadwinners, as well as on communities, which lose current and future workers, consumers, and voters.[23] Mass incarceration also increases barriers to employment, particularly for Black people. An experimental study comparing people with equivalent credentials demonstrated that having a criminal record reduced the likelihood of receiving a callback for a potential job by half for white people compared to nearly two-thirds for Black people.[24]

Confining children to under-resourced and economically and racially segregated schools has had powerful negative effects on their life chances, research has found. Conversely, increasing exposure to better funded schools, smaller classrooms, and more experienced teachers can reduce disadvantages associated with growing up poor and close much of the Black-white gap in students’ later risk of poverty. A series of court cases following the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas increased the enrollment of Black children in better-resourced schools. “The average effects of five years of court-ordered school desegregation led to about a 15 percent increase in [Black students’ later] wages and an increase in annual worktime by roughly 165 hours, which combined to result in a 30 percent increase in annual earnings,” one study found. The students also experienced a 25 percent increase in family income, higher marital stability, and an 11 percentage-point decline in poverty rates. The decline in adult poverty rates, as one would expect, is larger the more years Black students were exposed to desegregation. The study found desegregation orders had no negative impact on white students.[25] More recently, a study found that low-income children living in public housing in a Maryland county made large gains in reading and math scores over a period of seven years when attending low-poverty schools, compared with other children living in public housing and attending moderate- to high-poverty schools.[26]

A long and continuing legacy of private-sector discrimination by employers, real estate companies, and others has also restricted opportunities for people of color in jobs, housing, and education. For example, a well-known experimental study found that resumes with stereotypically white-sounding names were 50 percent more likely to receive a callback than equivalent resumes with stereotypically Black-sounding names.[27] And, beyond the discrimination associated with having a criminal record cited above, another experimental study found that Black and Latino individuals without such a record were no more likely to receive a callback or job offer than similarly qualified white individuals with a record.[28]

Economic security programs lifted 39 million people above the poverty line in 2017, including nearly 9 million children. Some 83 million people are below the poverty line when government assistance income and taxes are not considered, 44 million when they are. Government benefits and tax policies cut the poverty rate from 25.6 percent to 13.5 percent in 2017, and from 25.5 percent to 13.6 percent among children.

Economic security programs are particularly important in reducing racial disparities in child poverty. In 2017, government benefits and taxes reduced white child poverty by 7 percentage points, Black child poverty by 20 percentage points, and Latino child poverty by 16 percentage points, though poverty after accounting for government programs remains substantially higher among Black and Latino children than white children.

Economic security programs reduce gaps in child poverty by race and ethnicity by nearly half. Before counting government assistance and taxes, the poverty rate for Black children in 2017 was 26 percentage points higher than for white children. For Latino children, it was 21 percentage points higher. Once government assistance and taxes are accounted for, the poverty rate for Black children was 13 percentage points higher than for white children. For Latino children, it was 12 percentage points higher.

Economic security programs cut poverty significantly across all age and major racial and ethnic groups. For example, they lifted 23 million white, 6 million Black, 7 million Latino, and 1 million Asian people above the poverty line in 2017. See Table 1 (which doesn’t show details for smaller racial and ethnic groups due to data limitations).

| TABLE 1 |

| |

White |

Black |

Latino |

Asian |

All races and ethnicities |

| Children under 18 |

2,745,000 |

2,067,000 |

3,037,000 |

236,000 |

8,730,000 |

| Ages 18-64 |

6,508,000 |

2,718,000 |

2,712,000 |

343,000 |

12,739,000 |

| 65 years and older |

13,950,000 |

1,701,000 |

1,290,000 |

517,000 |

17,720,000 |

| All ages |

23,204,000 |

6,486,000 |

7,039,000 |

1,096,000 |

39,189,000 |

These calculations include federal and state income taxes and payroll taxes, but not sales, property, or other taxes (those data are not available). The joint effect of government assistance and taxes on reducing poverty would look smaller if it included these other taxes. That’s in part because many current state and local tax policies place a heavy burden on lower-income households. Indeed, enactment of still-current policies such as supermajority requirements to raise revenue, property tax limits, and sales taxes were closely intertwined with legislative efforts in the early 20th century to sustain racial disparities.[29] State governments can help reduce racial inequities by making stronger use of income taxes and taking other steps to improve their tax policies and better fund public services like schools, health care, and infrastructure.

The growing effectiveness of economic security programs helped bring down poverty rates. In 1970, economic security programs cut the poverty rate by 9 percent. By 2017 that figure had jumped to 47 percent. (See Table 2.)

| TABLE 2 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Racial and Ethnic Poverty Gaps |

| |

All |

White |

Black |

Latino |

Black/

White |

Latino/

White |

| 1970 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

25.1% |

19.9% |

50.8% |

43.6% |

30.9% |

23.7% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

22.7% |

17.3% |

48.4% |

44.2% |

31.0% |

26.8% |

| Percentage-point change in poverty |

-2.4% |

-2.5% |

-2.4% |

0.6% |

0.1% |

3.1% |

| Percent change in poverty |

-9% |

-13% |

-5% |

1% |

0% |

13% |

| 2017 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

25.6% |

21.6% |

37.3% |

32.0% |

15.6% |

10.3% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

13.5% |

9.8% |

20.9% |

20.1% |

11.1% |

10.3% |

| Percentage-point change in poverty |

-12.1% |

-11.9% |

-16.3% |

-11.9% |

-4.5% |

0.0% |

| Percent change in poverty |

-47% |

-55% |

-44% |

-37% |

-29% |

0% |

| Change: 2017 poverty rate minus 1970 poverty rate |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

0.5% |

1.8% |

-13.5% |

-11.6% |

-15.3% |

-13.4% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

-9.2% |

-7.6% |

-27.5% |

-24.1% |

-19.9% |

-16.5% |

The impact of government efforts to reduce child poverty has been even more remarkable. In 2017, government policies cut child poverty by 46 percent, with the refundable tax credits and SNAP accounting for most of this strong anti-poverty effect. In 1970, in contrast, child poverty actually was modestly higher after taking government benefits and taxes into account, because the federal tax code at the time taxed a substantial number of families with children into poverty (or deeper into poverty). Since that time, federal policymakers have established and expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit, which together lifted 5.1 million children above the poverty line in 2017. Nationwide implementation of SNAP in the 1970s and its increased effectiveness in reaching more eligible people have lifted millions of additional children out of poverty as compared to 1970.[30]

The increase in the effectiveness of economic security programs helped to reduce child poverty and racial disparities over the last five decades. In 2017, accounting for government benefits and taxes reduced poverty for white children by 7 percentage points, for Black children by 20 percentage points, and for Latino children by 16 percentage points. In 1970, in contrast, accounting for government benefits and taxes increased white and Latino child poverty modestly, and it reduced Black child poverty by 2 percentage points. (See Table 3.)

| TABLE 3 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Racial and Ethnic Poverty Gaps |

| |

All |

White |

Black |

Latino |

Black/

White |

Latino/

White |

| 1970 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

25.7% |

16.8% |

58.3% |

51.1% |

41.5% |

34.2% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

26.4% |

18.2% |

56.3% |

52.4% |

38.1% |

34.3% |

| Percentage-point change in poverty |

0.8% |

1.3% |

-2.1% |

1.3% |

-3.4% |

0.0% |

| Percent change in poverty |

3% |

8% |

-4% |

3% |

-8% |

0% |

| 2017 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

25.5% |

15.7% |

41.7% |

36.5% |

26.0% |

20.8% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

13.6% |

8.3% |

21.3% |

20.3% |

12.9% |

12.0% |

| Percentage-point change in poverty |

-11.8% |

-7.4% |

-20.4% |

-16.2% |

-13.0% |

-8.8% |

| Percent change in poverty |

-46% |

-47% |

-49% |

-44% |

-50% |

-43% |

| Change: 2017 poverty rate minus 1970 poverty rate |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

-0.2% |

-1.1% |

-16.6% |

-14.6% |

-15.5% |

-13.4% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

-12.8% |

-9.8% |

-35.0% |

-32.1% |

-25.2% |

-22.3% |

The official poverty measure is a revealing indicator of the state of the private economy for working-age adults (and their families) with low incomes. But unlike the SPM, it counts only pre-tax cash incomes and omits the impact of some key economic security programs such as SNAP, tax credits, and rental assistance that now constitute a much larger part of government assistance than 50 years ago. The official poverty rate therefore doesn’t accurately portray the overall financial well-being of low-income individuals or how that has changed over longer periods of time. The official rate fell much less sharply, from 12.5 percent in 1970 to 12.3 percent in 2017, than did the SPM over the same period, from 22.7 percent to 14.7 percent.

Further correcting for the underreporting of key government benefits in Census data shows an even bigger impact of economic security programs. Census’ counts of program participants typically fall well short of the totals shown in actual administrative records. Such underreporting is common in household surveys and can affect estimates of poverty. Starting in 1993 we can correct for underreporting by using data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Urban Institute for three types of government assistance: SNAP, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

When we use data that correct for households’ underreporting of these key government benefits, we find that economic security programs have even larger anti-poverty effects. In 2017, the most recent year for which these corrections are available, economic security programs lowered the SPM poverty rate from 25.6 percent to 13.5 percent — 1.2 percentage points lower than in SPM data without these corrections.

Correcting for underreporting makes an especially big difference in poverty for children, who are more likely than other age groups to receive SNAP and TANF. In 2017 government benefits and tax policies cut the number of children in poverty by nearly half in data with these corrections (from 25.5 to 13.6 percent), compared to about a third in data without these corrections (from 25.5 to 16.5 percent).

When analyzing overall poverty rates, we’ve found that correcting for underreported benefits does not make much of a difference in most years where we have both the corrected and the uncorrected data. The exception was during the Great Recession and its aftermath when the corrected figures helped reveal the large impact of temporary measures that boosted SNAP benefits.a We expect that if we were able to correct for underreported benefits in 1970, the impact would be small given that government assistance was relatively small in 1970, and SNAP (then food stamps) was not yet a national program with wide reach.

It’s worth noting that correcting for underreporting is particularly important when measuring “deep” child poverty, often defined as income below half of the poverty line, because underreported benefits make up a larger share of the total income of those with the lowest reported incomes.

Correcting for underreported benefits reveals that the share of children living in poverty fell but the share living in deep poverty rose during the first decade after policymakers made major changes in the public assistance system in the mid-1990s that made SNAP and TANF less available and accessible to poor families.b

a Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Economic Security Programs Cut Poverty Nearly in Half Over Last 50 Years,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated November 26, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-cut-poverty-nearly-in-half-over-last-50.

b Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Deep Poverty Among Children Rose in TANF’s First Decade, Then Fell as Other Programs Strengthened,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 27, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/deep-poverty-among-children-rose-in-tanfs-first-decade-then-fell-as.

Investing in children of color means investing in our future. Half of the children in the United States are children of color. Some 13 percent are Black, 26 percent are Latino, 5 percent are Asian, 5 percent are multiracial, and 1 percent are American Indian and Alaska Native.[31] Implementing policies that reduce these and all children’s exposure to poverty is an effective way of equipping every child in our country, regardless of their race or ethnicity, with opportunities to thrive.

An NAS expert panel that Congress charged with recommending ways to reduce child poverty noted that reducing child poverty — especially deep or prolonged poverty among young children — can be expected to provide longer-term benefits for both children and society by reducing future medical expenditures and other costs of poverty and by increasing children’s earnings and economic contributions in adulthood.[32] This conclusion is based on a growing body of research that suggests that various economic security programs not only help families address their basic needs today, but also can have longer-term positive effects for children, improving their health and helping them do better (and go further) in school, thereby boosting their expected earnings as adults.[33]

The better outcomes linked with stronger income assistance include healthier birth weights, lower maternal stress (measured by reduced stress hormone levels in the bloodstream), better childhood nutrition, higher reading and math test scores, higher high school graduation rates, less use of drugs and alcohol, and higher rates of college entry, the NAS committee noted.

Policymakers could substantially reduce poverty and racial inequities and advance opportunity for all children by adopting a range of policy proposals that the NAS panel evaluated, including expansion of housing vouchers and food assistance and making the Child Tax Credit larger and fully available to children in poor and low-income families, who now often get no credit or only a partial credit because their incomes are too low to qualify for the full credit based on its current design.

More recent analyses by Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy provide further evidence of how various policy proposals could substantially reduce child poverty and racial inequities. A child allowance like Canada’s would reduce racial and ethnic poverty gaps by over half.[34] A proposal to make housing vouchers available to all eligible families put forward by President Joe Biden during his campaign would reduce the white/Black poverty gap by up to a third and the white/Latino poverty gap by up to half. That proposal combined with two tax credit proposals endorsed by Vice President Kamala Harris would reduce racial and ethnic poverty gaps by even more.[35]

The NAS panel found that enacting either of two major policy packages would not only cut children’s poverty but also cut racial gaps in poverty by half.[36] (See Figure 3.) One plan expands SNAP benefits and housing vouchers. The other plan focuses on replacing the Child Tax Credit with a new universal “child allowance” of $2,700 a year per child, which would be fully available to the poorest families (without the minimum earnings requirement of the current Child Tax Credit); the package also contained smaller components such as a guaranteed child support program,[37] ending certain restrictions on lawfully present immigrants’ eligibility for government assistance, and raising the minimum wage. Both NAS plans also improve the EITC and expand child care assistance. The three policy changes in these packages with the largest impact on reducing child poverty are creating a child allowance, increasing SNAP benefits, and expanding housing vouchers.

Expanding Tax Credits Would Reduce Poverty Substantially

One way to essentially create a child allowance would be to make the full Child Tax Credit available to children in poor and low-income families even if those families lack earnings or have earnings that are too low. Currently, 27 million children in the families with the least income — those who need the credit most — receive only a partial credit or no credit at all because their families’ earnings are too low. Making the Child Tax Credit fully available, an idea gaining some momentum among policymakers, would allow all children in lower-income households to benefit fully from it.

The Biden Administration’s emergency COVID relief proposal, for example, would make the full Child Tax Credit available to poor and low-income households and raise the maximum Child Tax Credit from $2,000 to $3,000 for children between ages 6 and 17 and to $3,600 for children under 6. This expansion would lift 9.9 million children above or closer to the poverty line, including 2.3 million Black children, 4.1 million Latino children, and 441,000 Asian American children. It also would lift 1.1 million children out of deep poverty, that is, would raise their family incomes above 50 percent of the poverty line.[38] This expansion would reduce child poverty by 42 percent.[39]

The proposal would also expand the EITC for over 17 million adults not raising children at home who work at important but low-paid jobs. Adults not raising children are the lone group that the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty, partly because their EITC is so meager. Some 5.8 million childless adults aged 19-65 — including 1.5 million Latino and over 1 million Black childless adults — are taxed into or deeper into poverty. The top occupations that would benefit include cashiers, food preparers and servers, and home health aides.[40]

Both the Child Tax Credit and the EITC expansions in the Biden Administration’s relief proposal would expire after one year. However, policymakers have shown interest in making these two expansions a permanent feature of our tax code. One bill that would do so is the American Family Act (AFA) of 2019, introduced by Rep. Rosa DeLauro, Senator Michael Bennet, and others. Similarly, the Working Families Tax Relief Act, introduced in 2019 by Senators Sherrod Brown, Michael Bennet, Richard Durbin, and Ron Wyden, would reduce child poverty by more than one-fourth by making the Child Tax Credit fully available, increasing the amount of the credit for children under age 6, and expanding the EITC for both families with children and workers without minor children at home.[41]

Raising SNAP benefits also would reduce child poverty substantially. SNAP’s reach among children (roughly a quarter of all children receive SNAP) and its targeting — both through income-tested eligibility and the SNAP benefit formula (which assumes families will spend 30 percent of their net income on food) — give households most in need larger benefits. Research links receipt of SNAP benefits with long-term advances in health and well-being,[42] but roughly half of all households participating in SNAP are still “food insecure,” meaning they lack consistent access to enough food to support an active, healthy life.[43] This suggests that SNAP’s quite modest benefits — which average less than $1.40 per person per meal — are not sufficient to meet the needs of families in poverty. Additional benefits would increase families’ food spending, improve food security, and free up resources to meet other basic needs, like rent or health care.[44] The NAS report finds that a 35 percent increase in the SNAP maximum benefit would, by itself, reduce the number of children in poverty by one-fifth.[45] A 35 percent increase would bring the SNAP maximum benefit to just above the Agriculture Department’s (USDA) Low-Cost Food Plan, which is still a modest amount but would more adequately help families meet their food needs.[46]

The Biden Administration has recognized that SNAP benefits are too low, stating in a recent release that the SNAP benefit level “is out of date with the economic realities most struggling households face when trying to buy and prepare healthy food.... [T]he benefits fall short of what a healthy, adequate diet costs for many households.”[47] The Administration has indicated that the Secretary of Agriculture should consider revising the Thrifty Food Plan (which is the basis for the SNAP maximum benefit level). Moreover, this step is consistent with the 2018 farm bill, which called on the Agriculture Department to develop an updated Thrifty Food Plan based on “current food prices, food composition data, consumption patterns, and dietary guidance.”[48]

Rental assistance sharply reduces homelessness, housing instability, poverty, and other hardships. A growing body of research also finds that rental assistance can improve families’ health, as well as children’s chances of long-term success, particularly if it enables families to live in safe, low-poverty neighborhoods with good schools.[49] Due to inadequate funding, however, just 1 in 4 families with children eligible for housing assistance receives it.[50] The NAS report finds that providing vouchers to 4.9 million more low-income families with children, so that 70 percent of the eligible families with children not currently receiving housing assistance receive it, would itself reduce the number of children in poverty by more than one-fifth.[51]

Even a smaller expansion in housing assistance would have a significant positive impact on children’s living conditions. For example, creating an additional 500,000 housing vouchers for families with children under age 6 — and assisting interested families in moving to high-opportunity areas — could largely eliminate homelessness among families with young children and substantially reduce the number of children growing up in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, a Center analysis finds.[52]

Policymakers must also act to preserve affordable housing in gentrifying communities and improve neighborhoods where low-income families with children already live, regardless of whether they receive a housing voucher. As part of a longer-term strategy, they should invest in programs that increase incomes, enhance safety, and improve educational performance in high-poverty, low-opportunity neighborhoods and in communities of color, thereby improving the places where many families will continue to want to live.

Increasing the number of families in poverty that get help from TANF and the amount of direct cash assistance they receive would also lessen child poverty. TANF reached just 23 families for every 100 families with children in poverty in 2019, down from 68 in 100 families in 1996; if TANF had the same reach as it did upon its creation in 1996, about 2 million more families nationwide would have received cash assistance in 2019.[53] TANF benefit levels have declined as well; in 33 states they have dropped by at least 20 percent in inflation-adjusted value since 1996.[54] A majority (55 percent) of Black children in the country live in a state with benefits at or below 20 percent of the poverty line, compared to 40 percent of white children.[55] In a positive trend, 13 states plus the District of Columbia have raised benefits since July 2019; New Hampshire has set its benefit level at 60 percent of the poverty line and California is on a path to increase benefits to about half of the poverty line. More states should follow their lead, particularly the 33 states that have benefit levels below 30 percent of the poverty line.

Reducing Poverty Among Immigrants and Their Families

Significant progress in reducing poverty and broadening opportunity requires that government assistance programs better serve immigrants and their families. About 17 percent of all children and 42 percent of Latino children live in a family that includes a non-citizen.[56] The NAS poverty report included restoring eligibility for some immigrants to assistance programs such as SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) in one of its major policy packages.[57] Making programs accessible to individuals regardless of their immigration status would reduce poverty even further. Policymakers should follow the recent lead of California and Colorado, which made their state EITCs more inclusive for people by removing all immigration-related restrictions on eligibility.[58]

The Biden Administration should start by reversing the Trump Administration’s “public charge” rules, which have led many people to forgo assistance that they need and for which they are eligible out of fear that receiving these supports may harm their or their family members’ chance at changing their immigration status.[59] Research by the Urban Institute indicates that 31.5 percent of low-income adults in families that include children and at least one immigrant reported that they or someone in their family avoided participating in a benefit program in 2019 because of concerns about how benefit receipt would affect immigration status.[60] Forgoing benefits like Medicaid or SNAP is harmful at any time, but during the current economic and health crisis when many families are facing high levels of hardship, the implications are even more severe.

Ultimately, the nation needs comprehensive immigration reform that allows people in the United States without a documented status to obtain a lawful status and begin a reasonable, accessible pathway to citizenship. This will allow currently undocumented workers to earn fair wages and have critical labor protections they often lack now, help reduce fear among undocumented people and their children (who are often U.S. citizens), and allow everyone to access supports and services when they fall on hard times.

The impact on children would be large. Many children who are U.S. citizens have one or more parents who are undocumented. Even when children are eligible for assistance like SNAP or Medicaid, families often forgo that help out of fear that the parent who is undocumented will be discovered and deported. Even if children do access benefits, their parents aren’t eligible, which can leave the entire household short of the resources they need to put food on the table or pay the rent. And, when parents don’t have health coverage, they can miss out on care they need to work and care for their children effectively. Finally, children of parents who are undocumented can face high levels of fear and stress, as well as frequent moves, which can hurt their health development and school outcomes.

Addressing Discrimination and Its Impacts Key to Reducing Racial Disparities in Poverty and Opportunity

Further dramatic progress against racial disparities in poverty will be difficult without a stronger commitment to overcome bias and discrimination across society, including in housing, education, the legal system, and the workplace. This commitment will require stronger enforcement and oversight of anti-discrimination laws, including reviving anti-discrimination efforts that the Trump Administration suspended. For example, two harmful Trump Administration rules rolled back efforts to further fair housing goals: one making it far harder for individuals to successfully prove that they have been victims of housing discrimination and one reducing obligations of localities to understand and address housing discrimination.[61] The Biden Administration has announced plans to reverse these rules.[62] In addition, the federal government and local housing agencies can do more to help low-income households of color that receive Housing Choice Vouchers to understand their housing choices and move, if they wish, to neighborhoods with more job opportunities and stronger schools.[63]

In education, access to fairer opportunities will require substantially improving federal and state funding for instruction of low-income students, especially students of color. For example, policymakers can increase spending on Title I education grants and ensure that state and local school funding, which constitutes the bulk of school funding, is equitably distributed. Additionally, access to high-quality early learning programs, including through Head Start, preschool, and child care programs, is critical to improving educational outcomes. A boost in K-12 instructional spending has been found to be more than twice as effective at reducing a low-income student’s future risk of poverty (at age 30) if that student arrives at school after receiving Head Start’s preschool, nutrition, health screening, and parenting services.[64] There are also wide gaps in college access and completion. To improve higher education access and completion, especially for low-income students and students of color, states should increase funding for public colleges and universities and boost funding for need-based financial aid.[65]

In addition, to reduce bias in the criminal justice system and reduce incarceration rates, states should consider expanding the use of alternatives both to prison for non-violent crimes and to juvenile justice facilities and incarceration; decriminalizing certain non-violent activities, such as marijuana possession; diverting people with mental health or substance abuse issues away from the criminal justice system altogether; reducing the length of prison terms and parole/probation periods, including by reforming mandatory minimum sentences; reevaluating criminal justice fines and fees; and restricting the use of prison for technical violations of probation and parole. Such policies can have the added benefit of reducing state spending on prisons and jails.[66]

These kinds of policies will have stronger effects in a strong economy that provides ample employment opportunities to those seeking work. That requires robust stimulus policies during recessions and a continued commitment on the part of the Federal Reserve to pursuing full employment as an explicit and important policy goal. Moreover, we know that even when unemployment is low, some people face significant barriers to labor market success. Creating publicly subsidized employment programs that can help those struggling in the labor market — and expanding these efforts during periods of substantial slack in the labor market — can reduce employment disparities and expand economic opportunity.[67]

The economy has changed significantly since 2017, the latest year of data in our poverty series that corrects for underreporting of key government benefits. In 2017 the overall poverty rate had been declining for three consecutive years. Likewise, poverty for the white, Black, and Latino subgroups had also declined from 2014 to 2017. Even so, the shares of Black and Latino people living in poverty, 20.9 and 20.1 percent, respectively, were still both more than double the share of white people living in poverty, 9.8 percent. In other words, Black and Latino people were more than twice as likely to experience poverty than white people in 2017.

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic upended our economy — resulting in record job losses and a jobs hole that has yet to be filled. We will not have access to official poverty statistics for 2020 until the release of the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS) in September 2021. But many researchers have begun studying the pandemic’s effects on poverty using timelier data from the basic monthly CPS, a smaller and more limited version of the ASEC that is the source of official unemployment statistics, and the Census Bureau’s new Household Pulse Survey (HPS).

Monthly poverty rates likely fell in the early months of the pandemic, thanks to the strong support that the CARES Act provided, but then rose when major CARES benefits expired, according to estimates by researchers at Columbia University. By September 2020, the poverty rate was projected to have risen to 16.7 percent, from 15.0 percent in February (equivalent to over 5 million more people), with particularly large increases for Black and Latino people and for children, the researchers projected.[68] A second research team, at the University of Chicago and Notre Dame, similarly found monthly poverty rose in the pandemic (after an initial decline), as did gaps in the poverty rate by race.[69] Further, a recent study by the Department of Health and Human Services projected that the shares of Black and Latino people living in poverty increased more than the share of white people living in poverty in the final months of 2020.[70]

This finding is mirrored by racial and ethnic disparities in employment and hardship.[71] The prime-age employment-to-population ratios for Black and Latino people, that is, the share of Black and Latino people ages 25-54 with a job, started lower and declined more in the pandemic than the ratio for white people. This reflects pre-pandemic barriers to employment as well as how Black and Latino people are more likely than white people to work in the industries hardest hit by the health and economic crisis. Consequently, although hardship has increased overall amid the pandemic, Black and Latino people are more likely to experience hardship than white people, in terms of securing adequate food, making rent, and paying for usual household expenses.

The relief agreement that federal policymakers enacted late in 2020 will reduce hardship, but more relief will be needed. For one, the agreement’s expanded unemployment benefits expire in mid-March and the pandemic and its economic fallout show little sign of ending quickly. President Biden’s emergency relief proposal would extend expanded unemployment benefits through at least September and indicates that provisions should remain in place as long as they’re needed. The relief proposal also includes substantial resources to help millions of families afford housing, food, child care, and health care, and it temporarily expands the Child Tax Credit and the EITC. The package could cut child poverty in half and cut Black and Latino poverty by a third, according to researchers at Columbia University.[72]

Lasting progress in reducing poverty and the gaping racial and ethnic disparities in economic security and opportunity will require more than just recovering from the current crisis. Achieving these goals will require policies that provide more help to households struggling to afford the basics and that tackle head on the differences in education, housing, employment opportunities, and health care available across lines of race, ethnicity, immigration status, income, and place of residence.