- Home

- Federal Budget

- Working Families Tax Relief Act Would Ra...

Working Families Tax Relief Act Would Raise Incomes of 46 Million Households, Reduce Child Poverty

Senators Sherrod Brown, Michael Bennet, Richard Durbin, and Ron Wyden introduced legislation today that would substantially expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Based on an analysis of Census data, the proposal, known as the Working Families Tax Relief Act, would improve the economic well-being of 46 million low- and moderate-income households with 114 million people.

A significant body of research indicates that the EITC and CTC increase employment, reduce poverty, and improve children’s life prospects. The proposal’s EITC and CTC expansions — combined with overdue legislation to raise the minimum wage, provide paid family and medical leave, and other such policies — would help address the long-term wage stagnation that has affected households from all racial and ethnic backgrounds that earn low or modest wages.

The legislation would expand by roughly 25 percent the EITC for families with children. It also would substantially strengthen the very small EITC for workers who aren’t raising children in their homes — the sole group that the federal tax code now taxes into, or deeper into, poverty. The bill’s EITC expansions would, by themselves, benefit an estimated 35 million households with 75 million people.

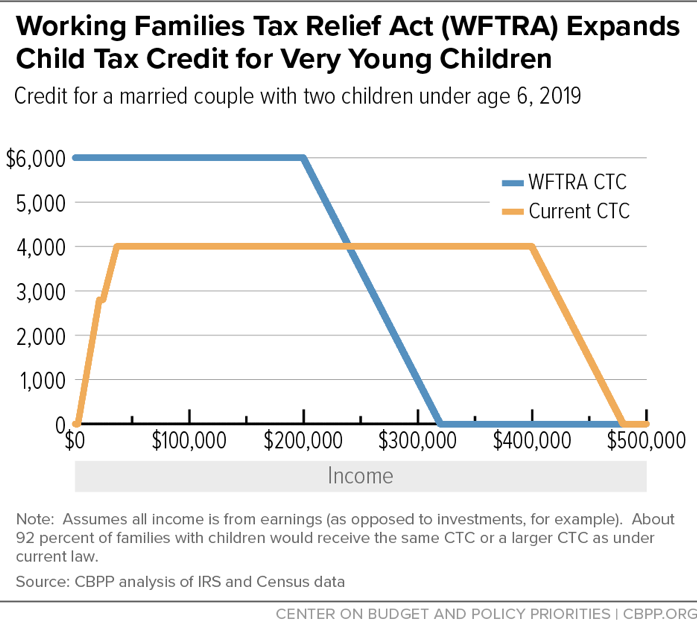

The bill also would make the CTC fully refundable so children in lower-income households, including those with little or no income, could benefit fully from it. Today, the CTC provides little or no help to millions of children and families with low incomes — the people who need it most. The proposal would also create a larger, fully refundable Young Child Tax Credit (YCTC) for children under age 6. Research shows this is a period of high importance and vulnerability in children’s lives, during which more adequate family income can improve poor children’s life opportunities. The Young Child Tax Credit would boost the CTC to $3,000 per child under age 6, from the CTC’s current $2,000 per child.

The bill’s CTC changes would benefit an estimated 43 million children, lifting more than 10 million of them above or closer to the poverty line. Its impact on deep poverty among children — that is, on children who live below half of the poverty line — would be dramatic. It would lift 1.3 million children out of deep poverty, reducing the deep child poverty rate by 37 percent (from 5 percent to 3 percent). In fact, a National Academy of Sciences committee that Congress charged with recommending ways to reduce child poverty recently made a similar policy a centerpiece of its package of anti-poverty proposals.

The bill would lift 29 million people above or closer to the poverty line, including 11 million children.Taking its EITC and CTC expansions together, the bill would boost the incomes of an estimated 24 million white families, 9 million Latino families, 8 million Black families, and 2 million Asian American families. It would lift 29 million people above or closer to the poverty line, including 11 million children.[1] The child poverty rate would fall from 15 percent to 11 percent (a 28 percent decline), using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (or SPM, which most analysts view as more accurate than the official poverty measure and which counts refundable tax credits as income). The overall SPM poverty rate would decline from 14 percent to 12 percent.

A few examples can help to illustrate the proposal’s impact:

- For a mother of a 4-year-old and a 7-year-old who makes $20,000 as a home health aide, the bill would raise her CTC by $2,210 and her EITC by about $1,460, for a combined gain of about $3,670.

- For a married couple where one spouse makes $45,000 as an auto mechanic and the other cares for their two young children full time, the bill would increase their EITC by about $1,460. They would also receive an additional $2,000 from the YCTC, for a total gain of about $3,460.

- Consider also a fast-food cook who works full time at the federal minimum wage and earns $14,500, only slightly above the poverty line for a single individual (which is estimated to be $13,340 in 2019). The cook now pays more than $1,250 in combined federal income and employee-side payroll taxes; as a result, the tax code pushes her below the poverty line. The bill would increase her EITC by about $1,530, so she would no longer be taxed into poverty.

In coming years, policymakers will likely debate how to restructure the 2017 tax law. The provisions of the Working Families Tax Relief Act should be a central part of that debate. The 2017 law largely overlooked the needs of working-class Americans while providing large tax cuts to wealthy households and profitable corporations, losing large amounts of revenue and swelling budget deficits, and opening the door to more tax gaming.[2] Undoing its ill-advised provisions would generate savings that could go, in part, to poor and working-class households through EITC and CTC expansions such as those that this bill proposes.

Policymakers also are expected to introduce other proposals that could benefit struggling working families, including a long-overdue increase in the minimum wage, more vigorous anti-trust enforcement, and other steps to restore workers’ bargaining power. The Working Families Tax Relief Act’s tax-credit expansions would complement such efforts by providing significant wage supplements to many families and individuals.

2017 Tax Law Ignored Stagnation of Working-Class Incomes

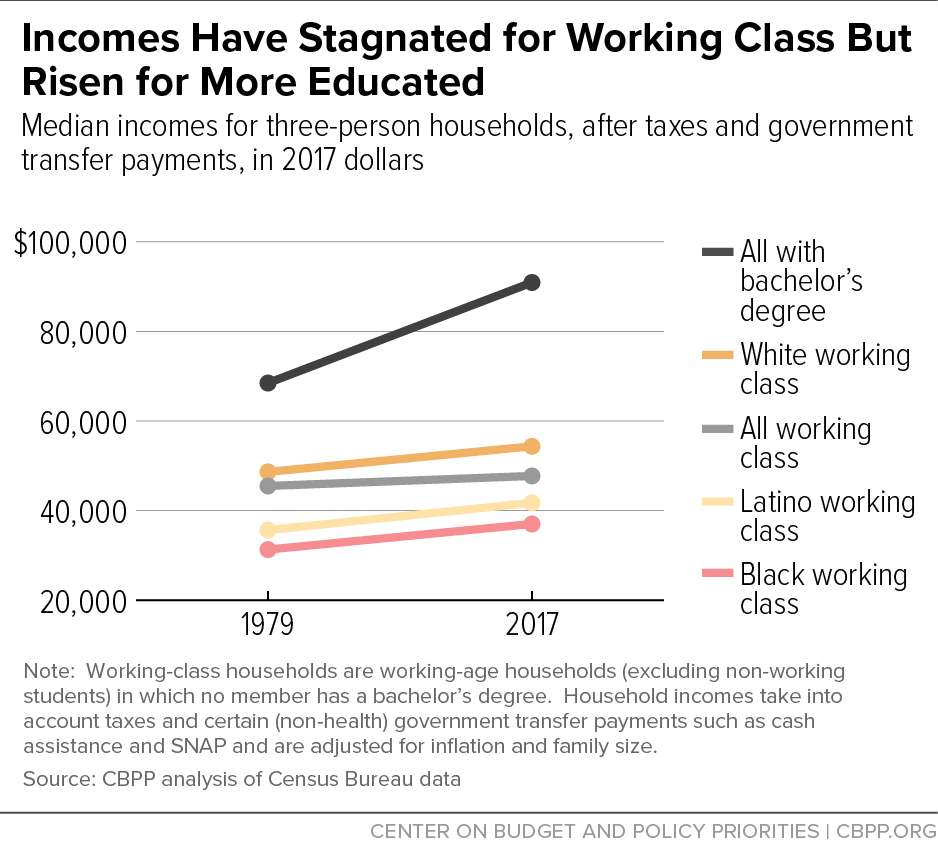

Working-class households — defined here as working-age households in which no one has a bachelor’s degree[3] — are a racially, ethnically, and geographically diverse group that has faced stagnant real incomes in recent decades. The median working-class household’s income grew only 5 percent in the 38 years between 1979 and 2017, after adjusting for inflation and accounting for changes in taxes and certain (non-health) government transfer payments such as cash assistance, SNAP (food stamps), and home energy assistance. In contrast, households at the very top of the economic ladder enjoyed rapid income growth over this period. And the median real income for households with a bachelor’s degree rose 33 percent.

Income stagnation has affected working-class Americans across racial and ethnic lines (see Figure 1), with the most severe consequences for working-class households of color, since they make less on average than white working-class households. Some 16 percent of working-class households are Black; 20 percent are Latino.

This reflects the particular challenges that working-class individuals of color can face, such as hiring discrimination: a recent analysis of 28 field experiments found persistent discrimination against Black and Latino workers.[4] In addition, a recent San Francisco Federal Reserve study found that a significant and growing part of the Black-white wage gap cannot be explained by other observable characteristics of workers such as education or age. “This implies that factors that are harder to measure — such as discrimination, differences in school quality, or differences in career opportunities — are likely to be playing a role in the persistence and widening of these gaps over time,” the authors concluded.[5]

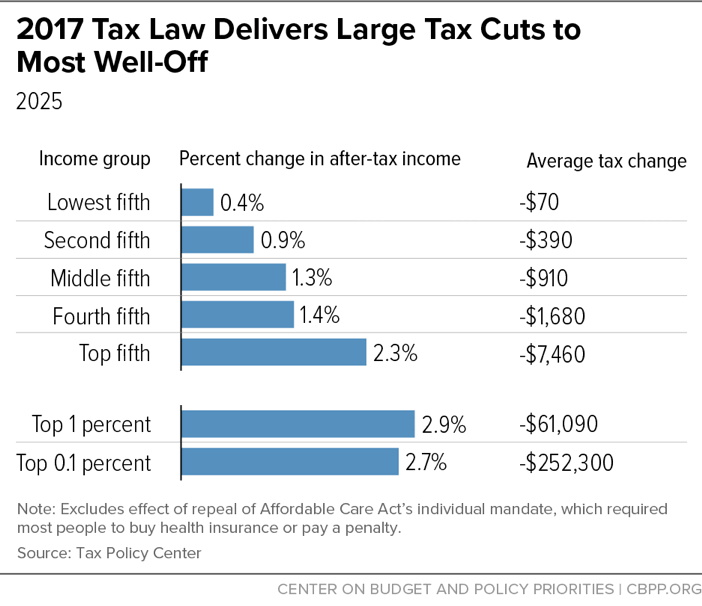

The drafting of a far-reaching tax law in 2017 provided an opportunity to boost working-class Americans’ after-tax incomes and help counter the growth in income inequality. Instead, the 2017 law largely ignored working-class Americans, and it increased inequality: in 2025, when the law will be fully phased in and before many of its provisions are scheduled to expire, the top 1 percent will receive tax cuts that increase their after-tax incomes by an average of 2.9 percent (or $61,100 per household), roughly three times the average 1.0 percent (or $400) gain for households in the bottom 60 percent. Households in the bottom 20 percent and the next-to-the-bottom 20 percent received the smallest tax cuts, measured as a share of income (see Figure 2). And measured in dollars, the top 1 percent will receive more in tax cuts than the bottom 60 percent of Americans combined.

That the 2017 tax law will increase income inequality is unsurprising given that its core provisions primarily (and in some cases, exclusively) benefit people with high incomes. These include its cut in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, the new 20 percent deduction for “pass-through” income, its doubling — to $22 million per couple — of the amount that wealthy households can pass to their heirs tax-free, its reduction in the top individual income tax rate to 37 percent, and its weakening of the Alternative Minimum Tax. In contrast, lawmakers drafting the law appear not to have considered strengthening the EITC, and their CTC changes did little for the families most in need.

Policymakers should revisit the 2017 tax law. In so doing, they should strongly consider reallocating some of the revenue they could recapture to strengthening the EITC and CTC, as the Working Families Tax Relief Act (and other bills) propose.

Bill’s EITC Expansion Would Directly Boost Working-Class Incomes

The EITC boosts working-class incomes: today, it reaches roughly 10 million working-class families with children (47 percent of such families), delivering an average tax credit to these families of $3,180. Research shows that the EITC also increases employment and improves children’s health and educational outcomes. One highly regarded study found that EITC expansions were the most important reason that employment rose among single mothers with children during the 1990s, with the EITC having a larger impact in increasing work than the strong economy or policy changes in cash assistance programs.[6]

A household’s EITC amount depends on its income and earnings, marital status, and number of children. Families with children and incomes up to roughly $55,000 in 2019 may be eligible, depending on these factors. The credit is refundable, meaning that if the credit amount exceeds a low-wage worker’s federal income tax liability, the household receives the balance as a tax refund. The refund can effectively offset workers’ federal payroll and excise taxes, as well as state and local sales, property, and other taxes.

The EITC has long enjoyed bipartisan support and is a “shovel-ready”[7] tool that policymakers can expand to help address stagnating working-class incomes. While some policymakers may be tempted to reach for new, untested policies to achieve the same ends, those can end up being grafted onto existing policies, creating unnecessary complexity, as the proliferation in recent decades of tax-advantaged savings accounts for retirement, education, and health care indicates. Policymakers should focus on scaling up effective policies that have been shown to deliver results. As noted, the EITC expansions in the Working Families Tax Relief Act would benefit an estimated 75 million people in 35 million households.

Fixing Holes in the EITC for Childless Workers

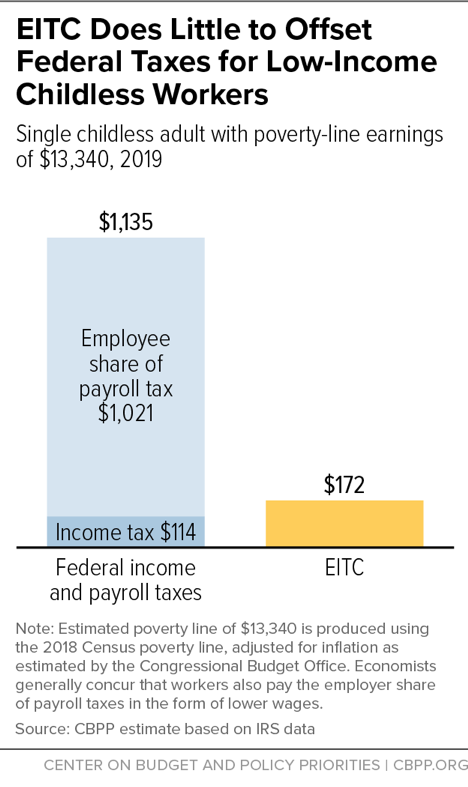

Among the legislation’s important elements are those addressing the EITC’s key shortcoming: the credit largely excludes working “childless” adults, including non-custodial parents, even though they can face labor-market challenges just as workers with children do. This shortcoming is a central reason why working childless adults are the lone group that the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty.

A childless adult earning poverty-level wages of $13,340, as a cashier, for example, will owe $1,135 in federal income and payroll taxes (counting only the employee share of the payroll tax). But he or she will receive an EITC of just $172 (see Figure 3). As a result, this individual is one of the more than 6 million low-wage childless workers whom the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty.

Today’s EITC also phases out at much lower income levels for childless adults than for families with children; a single worker loses eligibility for the EITC when his or her wages equal about $16,000. As a result, fewer than 10 percent of working-class households without children receive the EITC, as compared to nearly half of working-class households with children. Indeed, a full-time, year-round worker making $7.50 per hour makes too much to qualify for the childless workers’ EITC. Twenty-nine states and several cities have minimum wages at or above $7.50.[8]

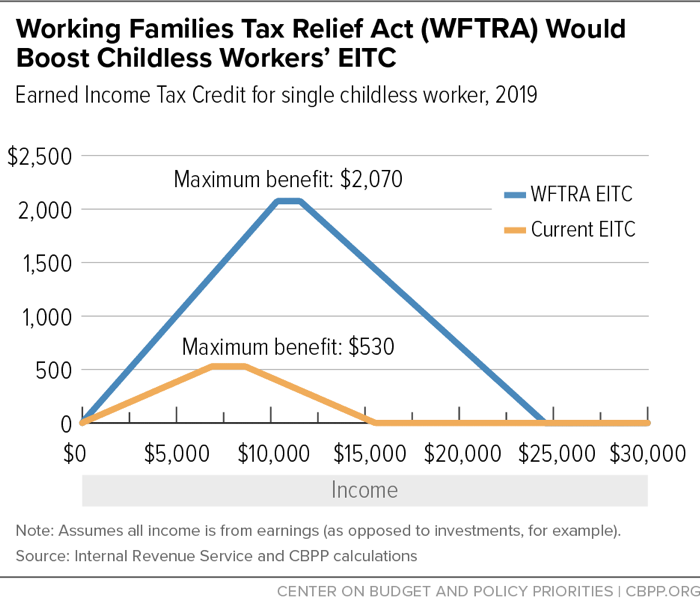

The bill addresses these issues by increasing the maximum EITC for childless workers from roughly $530 today to $2,100, and increasing the income limit to qualify for the credit from about $16,000 for a single individual to $25,000. It also expands the age range of workers eligible for the credit from 25-64 today to 19-67. (See Table 1 and Figure 4.) The above-mentioned cashier would see her EITC rise from $172 to $1,797, lifting her $662 above the poverty line.

| TABLE 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Working Families Tax Relief Act’s EITC Proposal for Childless Workers (2019) | ||

| Current Law | Proposal | |

| Phase-in rate | 7.65% | 20.00% |

| Phase-out rate | 7.65% | 15.98% |

| Income level at which credit stops phasing in (“first kink point”) | $6,920 | $10,370 |

| Income level at which credit begins to phase down (“second kink point”)* | $8,650 | $11,590 |

| Income level at which credit phases out entirely* | $15,570 | $24,569 |

| Maximum credit | $529 | $2,074 |

| Age range for qualifying tax filers | 25-64 | 19-67 |

* Figures shown are for unmarried individuals; comparable figures for married couples are $5,800 higher. All other figures are the same for unmarried individuals and married couples.

Strengthening the EITC for Families With Children

For families with children, the bill would increase by roughly 25 percent both the maximum credit and the rate at which the credit phases in as income rises. That produces an increase in the maximum EITC of about $880 for families with one child, $1,460 for families with two children, and $1,090 for families with three or more children. And while the legislation wouldn’t change the income level at which the EITC stops phasing in or the income level at which it starts to phase down, its increase in the maximum credit would raise the income level at which the credit entirely phases out. (See Table 2 and Figure 5.)

| TABLE 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working Families Tax Relief Act’s EITC Proposal for Families With Children (2019) | ||||||

| 1 Child | 2 Children | 3 Children+ | ||||

| Current Law | Proposal | Current Law | Proposal | Current Law | Proposal | |

| Phase-in rate | 34.00% | 42.50% | 40.00% | 50.00% | 45.00% | 52.50% |

| Maximum credit | $3,526 | $4,407 | $5,828 | $7,285 | $6,557 | $7,649 |

| Income level at which credit phases out entirely* | $41,094 | $46,610 | $46,703 | $53,622 | $50,162 | $55,351 |

* Figures shown are for unmarried individuals; comparable figures for married couples are $5,790 higher. All other figures are the same for unmarried individuals and married couples.

Bill Provides Federal Match for Puerto Rico’s New EITC

The Working Families Tax Relief Act would help Puerto Rico expand its new, Commonwealth-funded EITC, which took effect in January 2019.

Puerto Rico’s new EITC represents an important step to help combat the island’s high poverty rate and low labor force participation rate. Its size is modest, however, and Puerto Rico residents don’t qualify for the federal EITC. Under the new Puerto Rico EITC, the maximum credit for a family with two children is $1,500, compared to $5,830 for the current federal EITC.

The bill includes a federal matching mechanism that would enable Puerto Rico to roughly double its current EITC, with funds that the federal government would provide. This should increase labor-force participation by providing more incentive for people to work in the formal economy (rather than to work in the informal economy or be unemployed). That would strengthen Puerto Rico’s formal economy and thus the Commonwealth’s revenue collections, while also reducing very high poverty rates, especially among children.

Expanded EITC Needed to Address Challenge of Low-Wage Jobs

The decline over recent decades in real hourly wages for working-class Americans — the main driver of income stagnation among these households — underscores the need to strengthen the EITC, as well as to raise the minimum wage. The real median hourly wage fell by 8 percent between 1979 and 2017 for workers without a bachelor’s degree (from $17.36 to $16.00), while growing by 19 percent for workers with a bachelor’s degree (from $24.18 to $28.85).[9] These figures are in 2017 dollars.

Working-class households managed to mostly maintain their incomes over this period despite falling wages, for two reasons. First, they worked more. In particular, the share of 25- to 67-year-old women without a bachelor’s degree who are in the labor force grew from 54 percent to 63 percent.[10], [11] Second, lower taxes and more generous government transfers — especially increases in the EITC in the 1990s and 2000s — helped make up for the decline in real pre-tax wages.

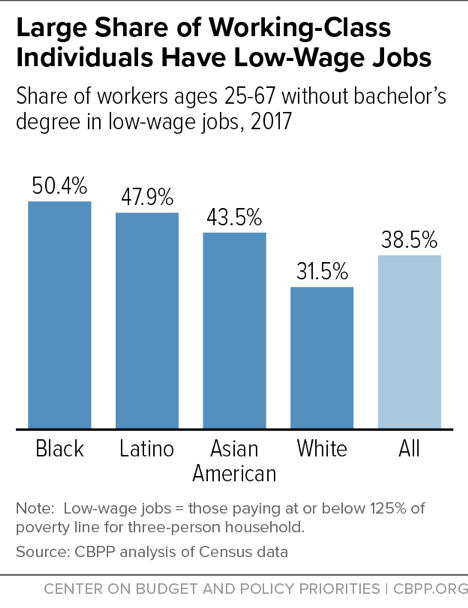

A significant share of working-class individuals continues to be employed in low-wage jobs. There is no universally recognized definition for low-wage work, but Boston College’s Vincent Fusaro and the University of Michigan’s Luke Schaefer provide one useful cutoff: the hourly wage required to keep a full-time, full-year worker with two children above 125 percent of the poverty line.[12] In 2017, this cutoff was $14.00 per hour; roughly 40 percent of workers without a bachelor’s degree did not make more than $14.00 per hour. A large portion of workers of every race lacking a bachelor’s degree had low-wage jobs, but the shares with low-wage jobs were highest among Black and Latino workers without a bachelor’s degree, about half of whom had low-wage jobs under this definition. (See Figure 6.)

The high prevalence of low-wage employment among working-class Americans will likely continue: three of the five occupations not requiring a bachelor’s degree that the Bureau of Labor Statistics expects to add the most jobs over the next decade paid a median annual wage of less than $25,000 in 2017 and the next two paid just above $25,000. (See Table 3.) A strong EITC likely will be essential in coming years and decades, along with strengthened labor-market policies, to ensuring that these workers have sufficient incomes to support their families.

| TABLE 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Wage Occupations Expected to Grow | ||||

| Five jobs not requiring a bachelor’s degree with most projected job growth, 2016-2026 | ||||

| 2016 Employment (Thousands) | 2026 Projected Employment (Thousands) | Projected job growth, 2016-2026 (Thousands) | Median Annual Wage (2018) | |

| Personal care aides | 2,016 | 2,794 | 778 | $24,020 |

| Combined food preparation and serving workers, including fast food | 3,452 | 4,032 | 580 | $21,250 |

| Home health aides | 912 | 1,343 | 431 | $24,200 |

| Janitors and cleaners, except maids and housekeeping cleaners | 2,385 | 2,621 | 237 | $26,110 |

| Laborers and freight, stock, and material movers, hand | 2,628 | 2,828 | 200 | $28,260 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bill’s CTC Improvements, Young Child Tax Credit Would Reduce Child Poverty

Even with a substantial increase in the EITC and other wage-boosting policies, many Americans would likely still be squeezed by the cost of raising a child (given the high cost of child care), additional medical expenses, and more. Families with young children can face special challenges. These families tend to have lower wages because they are often less advanced in their careers, and the high cost of child care for young children can force many parents to choose between paying that expense or getting by on just one income.

The CTC helps working families offset the cost of raising children, and its refundable component enables it to help many families with low earnings. But the CTC’s refundability is limited, and as a result, it partly or entirely leaves out substantial numbers of poor families with children. The Working Families Tax Relief Act would make the CTC a much more powerful tool for fighting poverty, particularly for very poor families with young children.

Fixing Flaws in 2017 Tax Law’s CTC provisions

Although the 2017 tax law increased the CTC by $1,000 per child, that increase largely bypassed 26 million children in low- and moderate-income working families due to its design. Some 11 million children saw a token increase of $75 or less because their families’ earnings were too low. Thus, a single mother with two children working full time at the federal minimum wage and earning $14,500 received only a $75 increase ($37.50 per child). Another 15 million children received an increase larger than $75 but less than the full $1,000 per child because the 2017 law capped the refundable amount of the credit at $1,400.[13]

The result was that millions of children in low- or moderate-income working families received a CTC increase of no more than $400 per child and often far less. And while the 2017 law limited the CTC increases for lower-income working families, it made the CTC available to families with incomes up to $480,000 a year for a married couple with two children (as compared to $150,000 under prior law). A family with two children making $400,000 received a $4,000 CTC increase from the 2017 law. (See Figure 7.)

To correct for these gaps and to improve the lives of millions of children growing up in or near poverty — and of young children generally — the bill would make the CTC fully refundable and create a larger credit for children under age 6 (see Figure 8).

-

Making the CTC fully refundable: For families with earnings too low to owe federal income tax, the current CTC is limited to 15 percent of a family’s earnings above $2,500, up to a maximum credit of $1,400 per child. The very poorest families with children receive nothing. A family with two children that earns $5,000 receives a credit of $375 ($187.50 per child.) And a family with two children with one earner working full-time, year-round at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour receives a CTC of $1,800 ($900 per child). These figures are far below the $2,000 per child available to a higher-earning family.

The bill would make the CTC fully refundable, so children with family incomes below the levels at which the CTC begins phasing down would receive $2,000 per child age 6 or older and $3,000 per child under 6. The proposal also would adjust the maximum credit amounts for inflation going forward.

To better target the CTC, the proposal would begin phasing the credit down at incomes of $200,000 for married couples and $150,000 for single parents. These levels are well below the 2017 tax law’s CTC thresholds of $400,000 and $200,000, respectively, but higher than the pre-2017 CTC thresholds of $110,000 and $75,000.[14]

- Creating a $3,000 Young Child Tax Credit: Under the legislation, families would receive an additional $1,000 CTC for a child under age 6, bringing the CTC to $3,000 per young child. More adequate family income in these critical early years can improve poor children’s life opportunities, research indicates. The $3,000 maximum credit would also be adjusted for inflation going forward.

Fully Refundable CTC Would Constitute Powerful Anti-Poverty Tool

A fully refundable CTC would be a powerful tool for fighting child poverty. Poor children suffer the worst outcomes when their poverty is “deep and persistent, especially during a child’s early years,” experts have noted.[15] Research indicates that toxic stress — that is, the activation of the body’s stress response system when a child experiences frequent, persistent, or excessive fear or anxiety due to abuse, neglect, violence, or severe hardship — can pose serious risks for young children, whose brains are in a critical stage of development. Leading researchers at Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child explain that the early years of life are a “period of both great opportunity and great vulnerability.”[16] Poor children have significantly higher rates of toxic stress than other children, research shows.[17]

Boosting the incomes of poor young children could therefore make a lasting difference for them. A National Academy of Sciences (NAS) committee of experts recently concluded that “the weight of the causal evidence indicates that income poverty itself causes negative child outcomes, especially when it begins in early childhood and/or persists throughout a large share of a child’s life. Many programs that alleviate poverty … have been shown to improve child well-being.”[18]

The better outcomes that are linked with stronger income assistance include healthier birth weights, lower maternal stress (measured by reduced stress hormone levels in the bloodstream), better childhood nutrition, higher school enrollment, higher reading and math test scores, higher high school graduation rates, less use of drugs and alcohol, more positive behavior, and higher rates of college entry, the NAS committee noted.

A fully refundable CTC is essentially a form of “child allowance,” an idea gaining momentum among policy experts and highlighted by the NAS committee. A child allowance is a periodic payment that is available to most or all low-income children and doesn’t exclude children whose parents are out of work. The NAS committee made a similar child allowance a centerpiece of its proposals to combat and shrink child poverty.

The Working Families Tax Relief Act takes a similar approach by broadening the CTC’s coverage for low-income children and expanding its size for young children (as would legislation recently introduced by Rep. Rosa DeLauro and others in the House and by Senator Michael Bennet and others in the Senate). The NAS committee found that building on the CTC in a comparable way while also expanding the EITC would sharply reduce deep poverty among children.[19]

Some may ask whether such a policy would discourage work among low-income families with children. The NAS committee considered this issue and concluded that making the CTC fully refundable, in tandem with increases in the EITC and in funding for child care (as part of a larger policy package[20]), would increase employment overall among low- and moderate-income households.

Moreover, while a fully refundable CTC would allow families who lack earnings in a given year to receive the credit, most families with children who don’t have earnings in a given year work most subsequent years, as a forthcoming CBPP analysis shows. The analysis finds that among families with children under age 17 where neither the head of the family nor the spouse worked in 1999, more than half worked in a majority of the subsequent observed years between 2001 and 2017, and most of the rest experienced a work-limiting disability.[21] It shouldn’t be surprising that many people temporarily exit the labor force when they have young children, either by choice or necessity (due to limited child care options or inflexible job hours, for example), and then return to work within a few years.

Finally, as the NAS panel noted, reducing child poverty — especially deep or prolonged poverty among young children — should provide longer-term benefits for both children and society by leading to reductions in future medical expenditures and other costs of poverty and by increasing the children’s earnings and contributions to the economy when they grow up.[22]

Bill’s EITC and CTC Expansions Would Boost Incomes, Reduce Poverty

The proposal’s EITC and CTC expansions together would benefit 46 million households that include 114 million people, of which 49 million are children, based on Census data. The average income boost among working-class families with children would be $2,000. Those receiving more income would include 24 million white households, 9 million Latino households, 8 million Black households, and 2 million Asian American households. The estimates also show approximately half a million American Indian and Alaska Native households and 1 million other non-Latino households would benefit.

As noted, the EITC and CTC are already powerful anti-poverty programs. They will lift a projected 10 million people out of poverty in 2019, including 6 million children, and reduce the severity of poverty for another 20 million Americans (by lifting them closer to the poverty line), including 7 million children.[23]

The bill would make substantial further progress. It would lift an additional 7 million people, including 3 million children, out of poverty and raise another 22 million — including 8 million children — closer to the poverty line. The child poverty rate would drop from 15 percent to 11 percent (a 28 percent decline), and the child deep poverty rate would fall from 5 percent to 3 percent (a 40 percent decline). The overall poverty rate would decline from 14 percent to 12 percent.

Bill Would Give IRS the Authority to Regulate Tax Preparers

The IRS launched an initiative in 2010 to improve the accuracy of tax returns that commercial tax preparers submit. The initiative grew out of IRS findings that the returns submitted by certain categories of commercial preparers had quite high rates of error, particularly EITC errors. Under this initiative, the IRS planned to register unenrolled preparers (those without a professional credential — i.e., those who aren’t CPAs, attorneys, or “enrolled agents”) and require that they pass a competency test and take annual education classes to stay abreast of tax-law changes.

The heart of the IRS initiative was struck down in federal court, however, because the court found that Congress hadn’t given the IRS the legal authority to regulate paid preparers in this way. That led both the Obama Administration and now the Trump Administration to request that Congress provide such legal authority so the IRS can reduce errors and overpayments. Senators Rob Portman and Ben Cardin have introduced legislation to do that, and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants has endorsed it. The Working Families Tax Relief Act includes the Portman-Cardin legislation.a

Improving the accuracy of tax returns that preparers submit can be particularly important in strengthening EITC compliance. The IRS’ National Taxpayer Advocate, Nina Olson, has noted that “Unenrolled preparers — those who are neither attorneys, certified public accountants, nor enrolled agents — account for more than three-fourths of EITC returns that are prepared by a paid preparer,” and unenrolled preparers not affiliated with a national tax preparation firm “are most prone to error.” In her 2018 report to Congress, Olson reiterated the need for Congress to provide the IRS with the authority to undertake its initiative to reduce error and fraud on commercially prepared returns.b

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Households, Individuals, and Children Benefiting From Working Families Tax Relief Act, by State | |||

| State | Number of Households | Number of Individuals | Number of Children |

| Total U.S. | 45,699,000 | 114,034,000 | 49,335,000 |

| Alabama | 747,000 | 1,837,000 | 787,000 |

| Alaska | 107,000 | 269,000 | 123,000 |

| Arizona | 1,018,000 | 2,610,000 | 1,164,000 |

| Arkansas | 476,000 | 1,187,000 | 523,000 |

| California | 5,465,000 | 14,344,000 | 6,079,000 |

| Colorado | 748,000 | 1,821,000 | 781,000 |

| Connecticut | 400,000 | 965,000 | 414,000 |

| Delaware | 120,000 | 298,000 | 132,000 |

| Dist. of Columbia | 81,000 | 183,000 | 81,000 |

| Florida | 3,069,000 | 7,345,000 | 2,943,000 |

| Georgia | 1,565,000 | 3,978,000 | 1,749,000 |

| Hawaii | 189,000 | 475,000 | 206,000 |

| Idaho | 259,000 | 668,000 | 303,000 |

| Illinois | 1,703,000 | 4,308,000 | 1,885,000 |

| Indiana | 985,000 | 2,430,000 | 1,085,000 |

| Iowa | 428,000 | 1,047,000 | 472,000 |

| Kansas | 415,000 | 1,040,000 | 476,000 |

| Kentucky | 697,000 | 1,689,000 | 725,000 |

| Louisiana | 751,000 | 1,846,000 | 815,000 |

| Maine | 187,000 | 414,000 | 164,000 |

| Maryland | 734,000 | 1,829,000 | 809,000 |

| Massachusetts | 788,000 | 1,866,000 | 770,000 |

| Michigan | 1,435,000 | 3,450,000 | 1,475,000 |

| Minnesota | 716,000 | 1,754,000 | 784,000 |

| Mississippi | 496,000 | 1,250,000 | 549,000 |

| Missouri | 923,000 | 2,213,000 | 952,000 |

| Montana | 163,000 | 370,000 | 154,000 |

| Nebraska | 266,000 | 681,000 | 317,000 |

| Nevada | 436,000 | 1,082,000 | 475,000 |

| New Hampshire | 153,000 | 350,000 | 142,000 |

| New Jersey | 1,049,000 | 2,661,000 | 1,137,000 |

| New Mexico | 334,000 | 841,000 | 368,000 |

| New York | 2,619,000 | 6,534,000 | 2,741,000 |

| North Carolina | 1,543,000 | 3,745,000 | 1,592,000 |

| North Dakota | 101,000 | 248,000 | 113,000 |

| Ohio | 1,707,000 | 4,058,000 | 1,767,000 |

| Oklahoma | 617,000 | 1,551,000 | 697,000 |

| Oregon | 591,000 | 1,375,000 | 571,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 1,688,000 | 4,059,000 | 1,729,000 |

| Rhode Island | 135,000 | 322,000 | 133,000 |

| South Carolina | 778,000 | 1,867,000 | 785,000 |

| South Dakota | 124,000 | 307,000 | 140,000 |

| Tennessee | 1,026,000 | 2,487,000 | 1,066,000 |

| Texas | 4,143,000 | 11,142,000 | 5,097,000 |

| Utah | 426,000 | 1,248,000 | 616,000 |

| Vermont | 83,000 | 187,000 | 75,000 |

| Virginia | 1,116,000 | 2,694,000 | 1,145,000 |

| Washington | 964,000 | 2,385,000 | 1,045,000 |

| West Virginia | 273,000 | 661,000 | 276,000 |

| Wisconsin | 778,000 | 1,858,000 | 819,000 |

| Wyoming | 83,000 | 203,000 | 92,000 |

Source: CBPP estimates based on 2015-2017 American Community Survey data and March 2018 Current Population Survey data.

| `APPENDIX TABLE 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households Benefiting From Working Families Tax Relief Act, by Race and State | ||||||

| State | American Indian or Alaska Native | Asian American | Black | Latino | White | Other |

| Total U.S. | 536,000 | 2,216,000 | 8,263,000 | 9,271,000 | 24,395,000 | 1,017,000 |

| Alabama | 4,300 | 7,600 | 288,000 | 30,000 | 422,000 | 10,000 |

| Alaska | 29,000 | 7,600 | 5,100 | 8,200 | 57,000 | 6,500 |

| Arizona | 74,000 | 27,000 | 60,000 | 371,000 | 460,000 | 20,000 |

| Arkansas | 4,700 | 5,400 | 108,000 | 36,000 | 316,000 | 10,000 |

| California | 31,000 | 670,000 | 399,000 | 2,495,000 | 1,587,000 | 145,000 |

| Colorado | 6,700 | 23,000 | 45,000 | 184,000 | 464,000 | 17,000 |

| Connecticut | 800 | 19,000 | 67,000 | 93,000 | 209,000 | 8,900 |

| Delaware | 600 | 4,400 | 36,000 | 15,000 | 63,000 | 2,700 |

| Dist. of Columbia | 100 | 2,200 | 54,000 | 9,500 | 16,000 | 1,500 |

| Florida | 7,200 | 76,000 | 690,000 | 845,000 | 1,376,000 | 53,000 |

| Georgia | 4,000 | 52,000 | 661,000 | 149,000 | 702,000 | 27,000 |

| Hawaii | 300 | 59,000 | 5,300 | 25,000 | 41,000 | 53,000 |

| Idaho | 5,500 | 2,800 | 2,000 | 35,000 | 209,000 | 4,500 |

| Illinois | 2,800 | 84,000 | 354,000 | 330,000 | 910,000 | 25,000 |

| Indiana | 3,400 | 19,000 | 137,000 | 69,000 | 746,000 | 17,000 |

| Iowa | 2,300 | 11,000 | 27,000 | 29,000 | 354,000 | 7,500 |

| Kansas | 4,800 | 13,000 | 40,000 | 53,000 | 295,000 | 11,000 |

| Kentucky | 1,500 | 9,500 | 87,000 | 23,000 | 572,000 | 10,000 |

| Louisiana | 5,600 | 12,000 | 341,000 | 35,000 | 368,000 | 8,800 |

| Maine | 2,000 | 2,000 | 3,000 | 2,300 | 175,000 | 4,100 |

| Maryland | 1,000 | 43,000 | 292,000 | 82,000 | 312,000 | 17,000 |

| Massachusetts | 2,200 | 54,000 | 87,000 | 140,000 | 481,000 | 22,000 |

| Michigan | 11,000 | 35,000 | 300,000 | 78,000 | 997,000 | 31,000 |

| Minnesota | 17,000 | 42,000 | 78,000 | 49,000 | 521,000 | 17,000 |

| Mississippi | 3,500 | 3,900 | 258,000 | 13,000 | 229,000 | 3,200 |

| Missouri | 6,300 | 16,000 | 158,000 | 39,000 | 696,000 | 18,000 |

| Montana | 16,000 | 1,600 | 800 | 5,500 | 140,000 | 3,300 |

| Nebraska | 4,600 | 6,700 | 21,000 | 32,000 | 197,000 | 5,400 |

| Nevada | 6,800 | 32,000 | 55,000 | 132,000 | 190,000 | 16,000 |

| New Hampshire | 400 | 4,800 | 3,100 | 5,500 | 137,000 | 2,600 |

| New Jersey | 2,100 | 92,000 | 208,000 | 282,000 | 443,000 | 18,000 |

| New Mexico | 50,000 | 4,200 | 8,000 | 163,000 | 104,000 | 4,300 |

| New York | 8,300 | 243,000 | 513,000 | 609,000 | 1,186,000 | 57,000 |

| North Carolina | 25,000 | 41,000 | 472,000 | 151,000 | 849,000 | 30,000 |

| North Dakota | 13,000 | 1,400 | 4,300 | 4,900 | 79,000 | 1,900 |

| Ohio | 3,100 | 31,000 | 329,000 | 70,000 | 1,253,000 | 38,000 |

| Oklahoma | 68,000 | 11,000 | 67,000 | 64,000 | 381,000 | 39,000 |

| Oregon | 9,300 | 22,000 | 16,000 | 84,000 | 436,000 | 22,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 3,200 | 56,000 | 271,000 | 161,000 | 1,178,000 | 28,000 |

| Rhode Island | 700 | 5,200 | 11,000 | 28,000 | 85,000 | 4,100 |

| South Carolina | 3,100 | 11,000 | 305,000 | 42,000 | 420,000 | 12,000 |

| South Dakota | 23,000 | 2,200 | 3,100 | 5,800 | 92,000 | 3,400 |

| Tennessee | 4,000 | 16,000 | 248,000 | 53,000 | 703,000 | 16,000 |

| Texas | 15,000 | 162,000 | 668,000 | 1,752,000 | 1,399,000 | 57,000 |

| Utah | 7,000 | 10,000 | 6,100 | 63,000 | 326,000 | 12,000 |

| Vermont | 600 | 1,700 | 1,000 | 1,100 | 78,000 | 1,700 |

| Virginia | 4,100 | 62,000 | 313,000 | 109,000 | 614,000 | 28,000 |

| Washington | 19,000 | 74,000 | 54,000 | 142,000 | 623,000 | 49,000 |

| West Virginia | 300 | 2,000 | 17,000 | 3,900 | 249,000 | 3,200 |

| Wisconsin | 14,000 | 22,000 | 83,000 | 62,000 | 590,000 | 13,000 |

| Wyoming | 3,500 | 500 | 800 | 8,800 | 68,000 | 1,700 |

Note: State totals in this table may not sum to state totals in table 1 because of discrepancies between the Current Population Survey and American Community Survey. Other (non-Latino) includes persons who identify as Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or more than one race.

Source: CBPP estimates based on 2015-2017 American Community Survey data and March 2018 Current Population Survey data

2017 Tax Law’s Child Credit: A Token or Less-Than-Full Increase for 26 Million Kids in Working Families

Working Families Tax Relief Act Would Help 46 Million Households, Cut Poverty and Deep Poverty

Policy Basics

Federal Tax

End Notes

[1] The bill would also reduce the income level at which the CTC begins to phase down from $400,000 ($200,000 for single parents) to $200,000 ($150,000 for single parents). Under the proposal, the CTC would phase out entirely at $300,000 for a married family with two children, one of whom is under age 6. The bill thus would modestly reduce after-tax incomes for about 3 million upper-income households.

[2] Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 14, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-tax-law-is-fundamentally-flawed-and-will-require-basic-restructuring.

[3] More specifically, households with at least one person between ages 18 and 67 who was not a full-time student and in which nobody has a bachelor’s degree. This includes both households with and without earnings.

[4] Lincoln Quillian et al., “Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2017.

[5] Mary C. Daly, Bart Hobijn, and Joseph H. Pedtke, “Disappointing Facts about the Black-White Wage Gap,” FRBSF Economic Letter, September 5, 2017, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2017/september/disappointing-facts-about-black-white-wage-gap/.

[6] Jeffrey Grogger, “The Effects of Time Limits, the EITC, and Other Policy Changes on Welfare Use, Work, and Income among Female-Head Families,” Review of Economics and Statistics, May 2003. Using different data, in another study, Grogger reached similar conclusions. Jeffrey Grogger, “Welfare Transitions in the 1990s: the Economy, Welfare Policy, and the EITC,” NBER Working Paper No. 9472, January 2003, http://www.nber.org/papers/w9472.pdf.

[7] David Autor, “US Labor Market Adjustment to China Trade Shocks,” Remarks at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 5, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXl3UTcuBJ4.

[8] U.S. Department of Labor, “Consolidated Minimum Wage Table,” March 29, 2019, https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/mw-consolidated.htm.

[9] Analysis of 25- to 67-year-olds using Center for Economic and Policy Research extracts of the Current Population Survey, http://www.ceprdata.org.

[10] Analysis of women using Center for Economic and Policy Research extracts of the Current Population Survey, http://www.ceprdata.org.

[11] One analysis found that low-income families’ incomes would have fallen between 1979 and 2013 were it not for the increased hours worked by women. See Heather Boushey and Kavya Vaghul, “Women have made the difference for family economic security,” The Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2016, https://equitablegrowth.org/women-have-made-the-difference-for-family-economic-security/.

[12] Vincent Fusaro and H. Luke Shaefer, “How should we define “low-wage” work? An analysis using the Current Population Survey,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review, October 2016, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2016/article/how-should-we-define-low-wage-work.htm. Aside from updating Fusaro and Shaefer’s to 2017, our figures differ in that we include all wage and salary workers, not just those paid on an hourly basis. For those not paid hourly, we use imputed hourly wages based on the reported hours worked the previous week from the Center for Economic Policy and Research’s extracts of the Current Population Survey.

[13] This refundability cap is adjusted for inflation going forward.

[14] These income thresholds are the income levels at which the CTC begins phasing down. A married couple with two children age 6 or older would still receive some CTC until its income reaches $280,000, as would a married couple with two young children until its income reached $320,000.

[15] Jeanne Brooks-Gunn and Greg J. Duncan, “The Effects of Poverty on Children,” The Future of Children, Vol 7. No. 2 (Summer/Fall 1997).

[16] Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, “From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts: A Science-Based Approach to Building a More Promising Future for Young Children and Families,” May 2016, http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/from-best-practices-to-breakthrough-impacts/.

[17] Greg Duncan, Katherine Magnuson, and Elizabeth Votruba-Drzal, “Boosting Family Income to Promote Child Development,” The Future of Children, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 109, https://www.fcd-us.org/assets/2014/07/24_01_05.pdf.

[18] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, National Academies Press, 2019, https://www.nap.edu/read/25246.

[19] Ibid.

[20] The NAS committee, charged by Congress with finding a way to cut child poverty and deep poverty in half in ten years, identified two policy packages that could meet this goal. A child allowance of $2,700 a year per child was the “centerpiece” of the larger of these two plans, along with expanding the EITC by 40 percent, expanding child care assistance by making the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit fully refundable, creating a child support assurance program, ending certain restrictions on lawfully present immigrants’ eligibility for government assistance, and raising the minimum wage. The EITC and child care policies would have large, positive impacts on employment, which would outweigh the small negative impact of the other policies in the package, the committee concluded. (The committee’s other policy package also relied on a mix of some policies that are tied to work, such as the EITC and child care assistance, with others that are not, including higher SNAP payments.)

[21] CBPP used the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to track non-working families with children starting in 1999. The PSID interviews families every two years, so our analysis is based on nine observed years between 2001 to 2017. “Worked in a majority of the subsequent observed years” thus means at least five out of those nine years. Families were limited to those that were interviewed in each of those years and were non-elderly (that is, the family head was aged 18-64) throughout. (Some individuals in the survey could not be located and interviewed in some years. Our analysis includes family heads present in at least eight of the nine subsequent observed years.)

[22] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

[23] Estimates are based on the March 2018 Current Population Survey and 2017 Supplemental Poverty Measure public use file. Poverty is measured using the Supplemental Poverty Measure and incorporates the effects of the 2017 tax law.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: