The House-passed bipartisan tax bill’s expansion of the Child Tax Credit takes an important step forward and would increase the credit for about 16 million children in families with low incomes in its first year. The expansion includes a so-called “lookback” provision — a modest but important provision designed to help families weather a year when their earnings temporarily decline by allowing them to use the prior year’s earnings to calculate their Child Tax Credit. This would ensure the design of the Child Tax Credit doesn’t make a financially challenging year even harder for parents and children.

The bipartisan expansion would lift as many as 400,000 children above the poverty line and provide more financial support to an additional 3 million children in families with incomes below the poverty line in the first year. That impact would rise to lift some half a million children or more above the poverty line and give more financial support to 5 million more children in families with incomes below the poverty line once the expansion is fully in effect for 2025.

Parents who work in low-paid jobs are often in a precarious position.[1] Nearly half of individuals with low earnings (below the 25th percentile) lack even a single day of sick leave, and most have no access to paid family or medical leave.[2] Moreover, because it is a stretch for them to make ends meet each month, they generally have only modest savings.

Families can face trying financial circumstances due to the birth of a child or when a family member gets sick or a parent’s employer lays off workers. The lookback provision acknowledges these realities and would provide a modest income buffer when a setback occurs or when people move through cycles of life that reduce their earnings. But the lookback provision is limited — if the family’s earnings don’t rebound after one year, then their Child Tax Credit would fall, and a family without any earnings for more than one year would lose their Child Tax Credit entirely.

The lookback would protect families who find themselves in these kinds of tough times or have a baby and take some time off to care for them. For example, Census data show that a mother’s earnings often fall the quarter after a baby is born but later rebound.[3] Child care disruptions and health issues, both temporary and chronic, can also reduce families’ earnings. It is not surprising that about half of the families who would benefit from the lookback provision have either a young child (under age 3) or the tax filer or their spouse has a disability.[4]

A set of far-fetched claims have been leveled against this modest nod to the real-world challenges parents face, alleging that the lookback would lead many parents with low incomes to strategically stop working. These arguments defy common sense and do not withstand scrutiny.

Considering the bipartisan Child Tax Credit expansion as a whole, Congress’s nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) found that “the proposed expansion of the child tax credit on net increases labor supply.” Though any impacts on work are likely to be modest, the direction of JCT’s conclusion is notable — the Committee determined that if anything, the bipartisan tax package will encourage employment. A wide range of analysts and outlets — including conservative tax experts at the American Enterprise Institute and the Tax Foundation — have also concluded the lookback poses no significant threat to employment.

A lookback provision has been enacted on a bipartisan basis six times over the last 15 years during economic downturns and for households who have been impacted by disasters. The bipartisan tax package recognizes that many families face financial hardship outside of recessions and natural disasters, including when a business closes, a family member is diagnosed with a serious illness, or when a new child arrives.

Longitudinal Census data show that a substantial majority of families who would benefit from the lookback provision in the bipartisan expansion have earnings in the current year, but their earnings have declined from the previous year. And about half of the families who would benefit from the lookback have a child under age 3 or a parent (or other adult caring for the children) with a disability.[5]

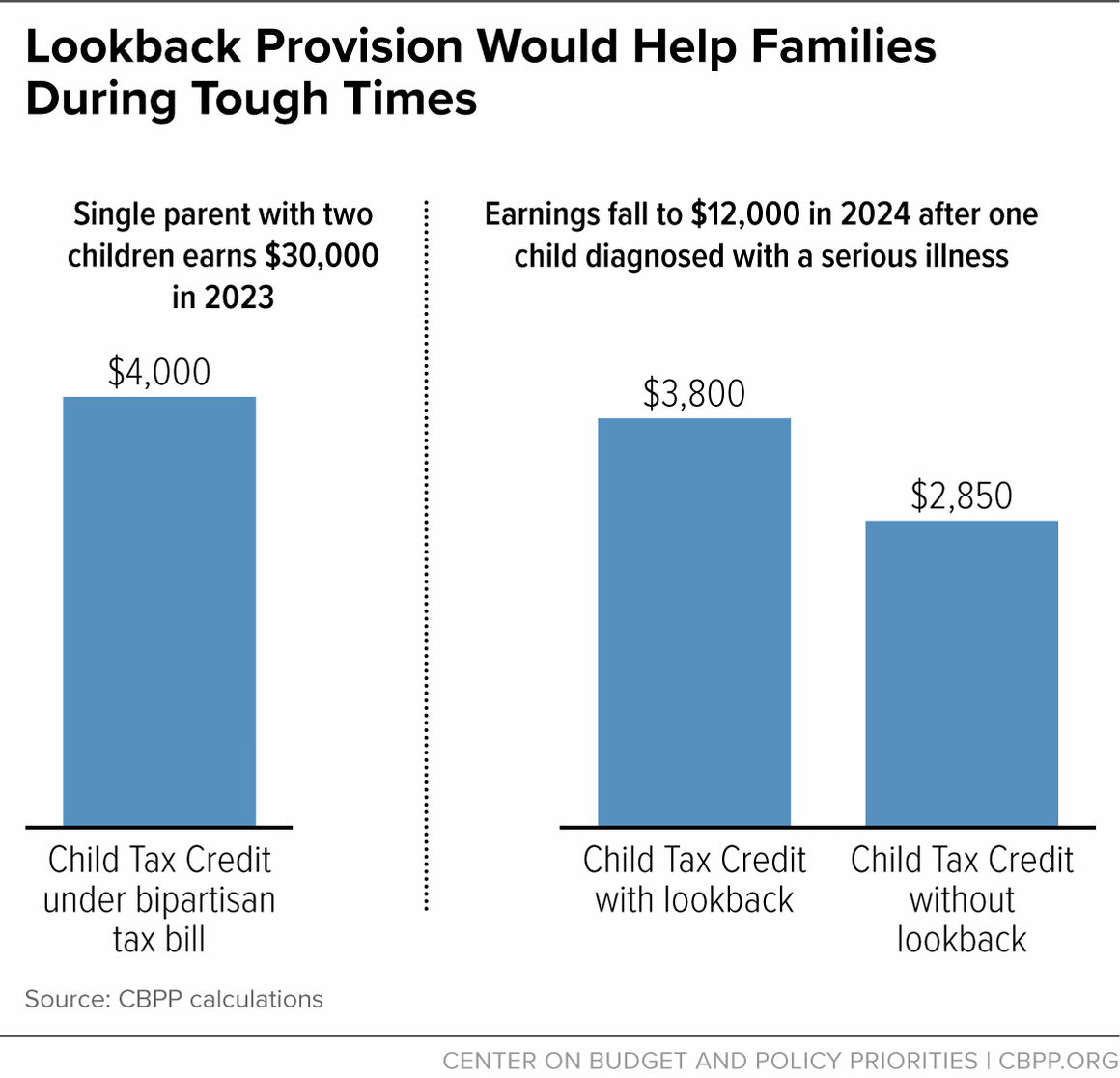

Here’s how the lookback works. Consider a single mother with two children who earned $30,000 as a nursing assistant in 2023, but who has to scale back her hours and has periods when she can’t work at all in 2024 after one of her children is diagnosed with cancer. As a result, her earnings fall to $12,000 in 2024. Without the lookback, she would be punished for her earnings decline — she would lose a large portion of the Child Tax Credit at the moment her family needs it most; however, the lookback protects her from a large drop in her credit for 2024.[6]

If her earnings don’t rebound the next year and she still earns $12,000 in 2025, then her 2025 Child Tax Credit would fall by $950 as compared to her credit in 2024 because the lookback would not allow her to use her higher 2023 earnings to calculate her credit for 2025. The lookback therefore provides meaningful but modest and temporary income security. (See Figure 1.)

Or consider a single father who works at a factory and earned $50,000 in 2023, but who gets laid off in February. He earns only $10,000 in 2024 while he gets new training and looks for a job, which may require the family to move. With the lookback provision in place for 2024, he would be protected from a large drop in the Child Tax Credit for his two children and receive a $3,800 Child Tax Credit (almost the full amount). If his earnings don’t go back up the next year, his credit for 2025 would fall by more than $1,500.

Some working families experience a year with little or no earnings. This can happen when families are contending with serious health issues, such as during a complicated pregnancy and the birth of a child with health issues, or when a parent has lost a job and has a difficult time finding a new one. The lookback would allow families in these situations to receive the Child Tax Credit for the first year in which they are out of work, but if the family does not have earnings the following year, the family would no longer be eligible for any help from the Child Tax Credit until a parent was able to return to work.

The nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation, Congress’ official tax policy evaluator, concluded that overall “the proposed expansion of the child tax credit on net increases labor supply” and that “the increase in aggregate effective labor supply relative to the baseline forecast is too small to be significant.”[7] In other words, the expanded credit would deliver gains to families with low incomes, without discouraging employment.

One flawed paper by Kevin Corinth and co-authors at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) alleges that for working parents, the “optimal strategy” under a lookback is to “consider exiting employment every other year.”[8] Other tax experts at AEI have publicly criticized the Corinth paper’s reasoning and evidence, as have many others across the political spectrum.[9]

The Corinth paper analyzes only the lookback provision (relative to current law), not the proposed expansion of the Child Tax Credit as a whole. If the study had incorporated all elements of the bipartisan tax bill’s Child Tax Credit expansion using the same assumption that labor supply is highly responsive to tax changes, the authors likely would have concluded that the expansion overall, including the lookback, would increase employment.

Corinth and his AEI co-authors present no direct, real-world evidence of a lookback leading to employment declines. Instead, making a set of highly implausible assumptions, the authors conclude that hundreds of thousands of single parents, mostly mothers who earn on average $37,500 per year (by the authors’ calculations), would stop working one year and start again the next because the lookback provision protects their Child Tax Credit of up to $2,000 per child.

The paper also argues that some non-working parents, though fewer, would be drawn into the labor force by a lookback, diminishing the net employment impact, but the prediction about some parents not working because of the lookback has garnered most of the attention and been used to argue that the lookback provision is harmful.

Here are just two of the many implausible assumptions one has to believe to take seriously the prediction that large numbers of single parents who otherwise would work would quit due to the lookback:

- Hundreds of thousands of families earning just $37,500 on average don’t need those earnings to pay rent, buy school clothes, maintain a car, or meet their other expenses, and so would choose not to work when they otherwise would have. Indeed, the authors do not fully account for how a single parent would be able to make ends meet, provide for their children, and not experience serious hardship after forgoing $37,500 in earnings (as well as the Earned Income Tax Credit they would have received for the year). “It would be a big gamble for a mom who is her children’s sole source of earned income,” wrote Leah Libresco Sargeant of the Niskanen Center. “You're forfeiting a lot of salary, just because you have locked in [the Child Tax Credit benefit].”[10]

- The parents who would quit their jobs for a year don’t understand that voluntarily leaving the workforce would have negative impacts on their ability to get a new job and receive pay raises over time — but they do have full knowledge of the fine details of the evolving Child Tax Credit law and make precise calculations about a so-called “optimal strategy” to exit and re-enter the labor force. As Sargeant from Niskanen notes, “And every mom knows it’s hard to count on being able to reenter the workforce once you step away.”[11]

Even if one accepted these far-fetched assumptions, the Corinth paper predicts that on average, a lookback would cause employment to decline by about 150,000 people on net each year — a miniscule share of the 167 million-person U.S. workforce (about .09 percent of the workforce). But virtually all other tax analysts and experts who have weighed in do not find the Corinth model’s assumptions credible, suggesting the lookback’s impacts on work are likely to be even smaller.

A host of conservative analysts, including others at AEI, have criticized the paper. Ryan Ellis, president of the Center for a Free Economy wrote, “No one is going to zig zag in and out of the workforce every year just to get a partially refundable child tax credit. That’s silly, and if people are worried about that, they shouldn’t be.”[12] The Tax Foundation similarly concluded, “In our assessment, a major labor supply effect from a one-year lookback period is unlikely.”[13]

Kyle Pomerleau of AEI notes that the provision of the bipartisan proposed expansion that would phase in the Child Tax Credit faster as earnings rise for families with more than one child would increase work incentives for many families. Corinth and his AEI colleagues acknowledge that their paper does not account for this, only providing predictions of the employment impacts of the far smaller lookback provision.

Pomerleau adds that the lookback’s work incentive impact is likely small and its direction unclear because in any given year, if a parent works they can ensure the Child Tax Credit for the current year and as insurance if they fall on unexpected tough times the next year.[14] (The Corinth predictions do not account for the way the lookback helps parents hedge against their own financial uncertainty.[15])

Pomerleau writes, “Under this provision, generating earned income this year does not necessarily generate a credit for this year because a tax filer could use last year’s earned income to calculate the credit. However, working this year means that the tax filer will generate earned income that they could use next year for purposes of the CTC. The exact impact of the lookback provision on work incentives depends on a few factors, but should not have a large impact in the aggregate either way.”[16]

A wide range of other experts have echoed the conservative consensus. Jacob Goldin, a law professor and economist at the University of Chicago, wrote, “At the end of the day, are people really going to walk away from their jobs just because they can qualify for a bit more CTC? There’s no evidence that they did following the (much larger) 2021 reform.”[17] Goldin cited a May 2023 American Economics Association research paper that concluded, “We do not find strong evidence of a change in labor supply for families receiving the credit,”[18] consistent with most studies of the American Rescue Plan’s expanded Child Tax Credit.[19] Jack Landry of the Jain Family Institute concluded that, “When subject to scrutiny, the evidence that the modest reforms in the bipartisan [Child Tax Credit] expansion will affect parents’ work decisions is virtually nil.”[20]

The Lookback Provision Maintains the Tie to Employment and Does Not Make the Child Tax Credit “Fully Refundable”

The 2021 Rescue Plan’s temporary Child Tax Credit expansion increased the maximum credit and provided the full credit to children in low-income families regardless of their earnings. This is known as making the credit “fully refundable.”

We strongly support a fully refundable Child Tax Credit — evidence suggests that it would drive down child poverty rates without large impacts on employment and improve children’s future educational and labor market outcomes. Canada, like many wealthy nations, has a child allowance available to all children in low-income families regardless of their parents’ earnings and has expanded it in recent years; those expansions were not found to have any significant impact on parental employment. Canada’s labor force participation rate among women is higher than in the U.S. As with any cross-country comparison, there are of course some differences between Canada’s situation and the U.S.’s. But most studies forecasting the potential impacts of a permanent Rescue Plan Child Tax Credit in the U.S. also predict relatively modest effects on employment as a share of the workforce, with more than 99 percent of working parents continuing to work.[21]

We support full refundability, but this modest lookback provision is not full refundability.

Under the bipartisan Child Tax Credit expansion with the lookback provision, the Child Tax Credit remains tied to a parents’ earnings. The lookback simply holds that if a family’s earnings fall one year, the prior year’s earnings can be used to calculate their credit. If, however, a parent remains out of work or has very low earnings beyond a single year, they would lose their Child Tax Credit (if they are out of work entirely or have earnings below $2,500) or receive a smaller one (if their earnings are below the level needed to qualify for the full credit).

The tie to parental employment remains firmly in place.

The Congressional Budget Office projects that in 2025, when the bipartisan Child Tax Credit expansion would be fully in effect, the U.S. economy will stand at $29 trillion; JCT projects that the cost of the lookback provision would be $739 million[22] — or 0.003 percent of GDP.[23] Its impact on labor supply would be exceedingly small and, as some have noted, it is not even clear whether the provision’s impact is positive or negative.

But it is clear that for families experiencing a temporary disruption to or decline in their earnings due to a child being born, a layoff, or a serious illness in the family, the lookback provision can provide a temporary modicum of relief, reducing the likelihood of serious financial hardships and making things a little easier for parents under real financial strain. It is deeply unfortunate that this modest help to working families facing a difficult year has resulted in outsized attacks based on assumptions that seem disconnected from the real lives of parents who work hard in low-paid jobs and sometimes face financial challenges.