Non-elderly adults without children, one of the largest demographic groups in the United States, are left out of many economic and health security programs that are effective at reducing poverty and expanding access to health coverage for other groups. Partly as a result, their poverty rate has not fallen in recent decades as it has for children, seniors, and non-elderly adults with children, a comprehensive assessment of poverty trends before the pandemic shows.

More than 1 in 3 people in the United States — 117 million individuals — is 18 to 64 years old and does not have a child under 18 in their family (referred to in this report as “non-elderly adults without children”). This group is demographically diverse, covering those just past high school age to nearing retirement, reflecting all races and ethnicities and levels of education, and representing every region of the country.

Membership in this group is not static, and most adults experience some period of time between ages 18 and 64 when they are not caring for children under 18. Some non-elderly adults without children may provide support for children from a previous relationship outside the home. Others help support grown children ages 18 and older, either in the same home or another home. Still others have chosen not to have children or are unable to have children.[1]

Despite the large number of these individuals and their widely ranging circumstances, unless they can document a severe disability, economic security program rules tend to expect them to work in order to receive benefits; even then, help available to people in this group is generally very modest. These programs offer little assistance when these adults encounter job loss, their work hours are cut short, their wages are too low to pay the bills, they face illness or job discrimination, an older relative requires full-time care, their car breaks down, or other needs arise.

For example:

- Non-elderly adults without children have little access to cash assistance. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program serves families with children, and general assistance programs, which operate in just 25 states, served less than half a million individuals nationally in December 2019, with most programs limited to people with a disability or other health condition.

- The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is far less generous for non-elderly adults without children than for families with children, and as a result, the federal tax system taxes some 5 million of these adults into — or deeper into — poverty.

- In many cases, non-elderly adults without children who are out of work can only receive food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) for three months while unemployed in any three-year period, a restriction not imposed on families with children or seniors.

- Rental assistance programs, which have extremely limited funding, serve fewer than 1 in 5 eligible non-elderly adults without children, tending to prioritize serving people with disabilities and seniors.

- Because 14 states have not implemented the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, this group often lacks health insurance.[2]

- And, while unemployment insurance programs are open to workers regardless of whether they have children, outside of the current period when large-scale expansions are in place, most low-paid workers do not qualify for unemployment benefits when they lose their jobs because of a host of restrictive eligibility criteria.

Economic security programs play an increasingly important role in bolstering income for many people — not only tiding them over in times of crisis but also helping to soften the impact of weak wage growth, rising income inequality, ongoing racial and gender discrimination, and other forces that have led the fruits of a growing pre-pandemic economy to be unevenly shared across households. These programs’ income-boosting role has remained notably weaker, however, for non-elderly adults without children compared to other groups.

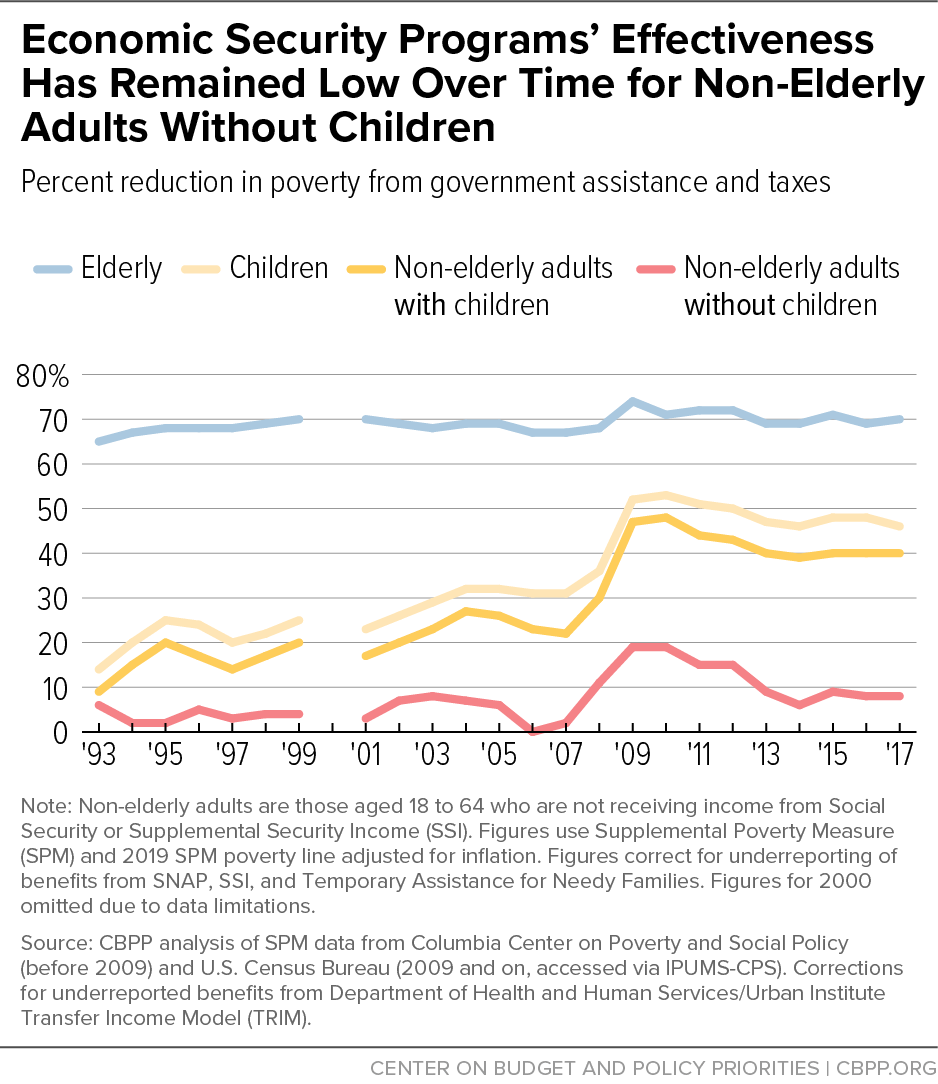

From 1993 to 2017, improvements in economic security programs led to falling poverty rates overall and for families with children — but not for those without children. For example, the EITC for non-elderly adults without children has remained essentially unchanged since it was added to the EITC in 1993; meanwhile, the EITC for families with children has been expanded several times since its inception, resulting in an average credit amount that was more than ten times greater for those with children in tax year 2017 ($3,191 for a family with children compared with $298 for a family without children).[3]

Largely as a result, non-elderly adults without children are the only major group whose poverty rate, measured comprehensively with the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) after correcting for underreporting of key government benefits, has not declined since 1993. (See Figure 1.)

Because many economic security programs offer greater support to non-elderly adults without children if they receive major disability benefits, we are especially interested in those who do not receive these benefits. Specifically, this report focuses on those who do not receive Social Security or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits (an estimated 106 million out of 117 million total non-elderly adults without children in 2017).[4]

The COVID-19 recession, while harshest in many ways for households with children, has also hurt non-elderly adults without children. About 1 in 8 non-elderly adults not living with children who were surveyed in late 2020 reported that their household didn’t get enough to eat sometimes or often during the last seven days, three times the share who ever lacked enough to eat in all of 2019.

Policymakers have adopted various temporary relief measures to mitigate the health and economic harm caused by COVID-19. This analysis examines economic security programs prior to the current crisis to encourage policymakers to enact longer-term changes to these programs that will help ensure a more equitable recovery.

The 106 million non-elderly adults without children in the family and without income from Social Security or SSI are a diverse group with widely varying needs (see Figure 2):[5]

- 17 percent are aged 18 to 24 and 27 percent are age 55 and older.

- 48 percent are female.

- 36 percent identify as people of color, with 12 percent identifying as Black, 15 percent Latino, 6 percent Asian, and 2 percent as another race or multiple races; 64 percent are white.[6]

- Among those aged 25 and older, 39 percent have at least a four-year college degree, while 34 percent have a high school diploma or less.

- 10 percent are full-time students.

- Nearly 5 percent are veterans.

- 88 percent live in metropolitan areas.

- 83 percent share a household with others.

- More than one-third (37 percent) live in the South, 24 percent in the West, 21 percent in the Midwest, and 18 percent in the Northeast.

About 83 percent worked at least one week in the previous year. (When excluding full-time students, 85 percent worked at least one week in the previous year.) They are most likely to work in office and administrative support occupations; management positions; sales and sales-related jobs; transportation and material moving occupations; and education, training, and library jobs.

Despite not receiving income from Social Security or SSI, 6 percent report having a health problem or disability that prevents or limits their ability to work. Many may have physical or mental health conditions that hinder their ability to work but that do not meet the strict eligibility criteria for those programs, which require that applicants demonstrate that their disability will last at least 12 months or result in death and that it precludes them from engaging in substantial work.[7] Others may be partway through the months- or years-long application process, or may fail to receive benefits for other reasons.

Non-elderly adults without children are not a static population; as with many individuals, their employment status, economic status, and health or disability status may change over time. Additionally, whether they are deemed to be with or without children may vary as their family composition changes, due to life changes such as divorce, a new marriage or partnership, shifting child custody arrangements, or the birth of a child.

In 2017, 9.4 percent of non-elderly adults without children lived below the official poverty line ($12,752 for a single person and $16,414 for a couple without children), while 20.2 percent — 1 in 5 — lived below 200 percent of the poverty line ($25,504 for a single person and $32,828 for a couple without children). Many policies designed to support low-income individuals focus on serving the population under 200 percent of the official poverty line.

This low-income group of non-elderly adults without children tends to be younger than non-elderly adults without children as a whole — 27 percent are aged 18 to 24 — and slightly more likely to be female (50 percent versus 48 percent). These low-income individuals are also disproportionately Black or Latino — 18 percent and 21 percent, respectively — due to historical and ongoing discrimination in education, housing, employment, and criminal justice that has systematically limited opportunity and resulted in higher levels of economic insecurity.[8]

Compared to all non-elderly adults without children, this low-income group has much lower educational attainment; 53 percent have at most a high school diploma, while only 21 percent — nearly half the rate for the group as a whole — have a four-year college degree or higher.[9] They are slightly more likely to live in rural (non-metropolitan) areas (13 percent versus 11 percent), to live alone (23 percent versus 17 percent), and to live in the South (42 percent live in the South, a quarter in the West, and 19 percent and 15 percent in the Midwest and Northeast, respectively).

We find considerable differences in work status between the low-income group and the group of all non-elderly adults without children. While 83 percent of the overall group worked at least one week in the previous year, only 58 percent of the low-income group did. (When excluding full-time students, 85 percent of the overall group worked at least one week in the previous year, compared with 61 percent of the low-income group.) The share of low-income individuals reporting a health problem or disability that prevents or limits their working (among those not receiving income from Social Security or SSI) is more than double that of the group as a whole.

The low-income group is more likely than the full group of all non-elderly adults without children to work in food preparation and serving roles and cleaning and maintenance jobs. These and other low-paying jobs often come with irregular schedules and only part-time hours when workers would prefer to work full time, which can make it more difficult for these workers to retain employment and advance in their careers.[10] Low-wage jobs also are more likely to lack benefits such as health insurance and paid sick leave or other paid leave, which might result in their leaving a job earlier than they otherwise might in order to manage their health or the health of a loved one. For example, only 52 percent of workers in jobs with average hourly wages in the bottom 25 percent of the wage distribution had paid sick leave in March 2020, compared with 78 percent of all workers.[11]

See Appendix for more demographic detail.

As noted above, most low-income non-elderly adults in the United States work, and economic security programs often expect them to work (or to have documented a severe disability) in order to qualify for benefits. However, maintaining uninterrupted work can be difficult because of the unstable nature of many low-paying jobs and a variety of other employment barriers. Consequently, examining this group’s work status over a period of months reveals considerably more employment than a point-in-time estimate of unemployment in a single month shows.

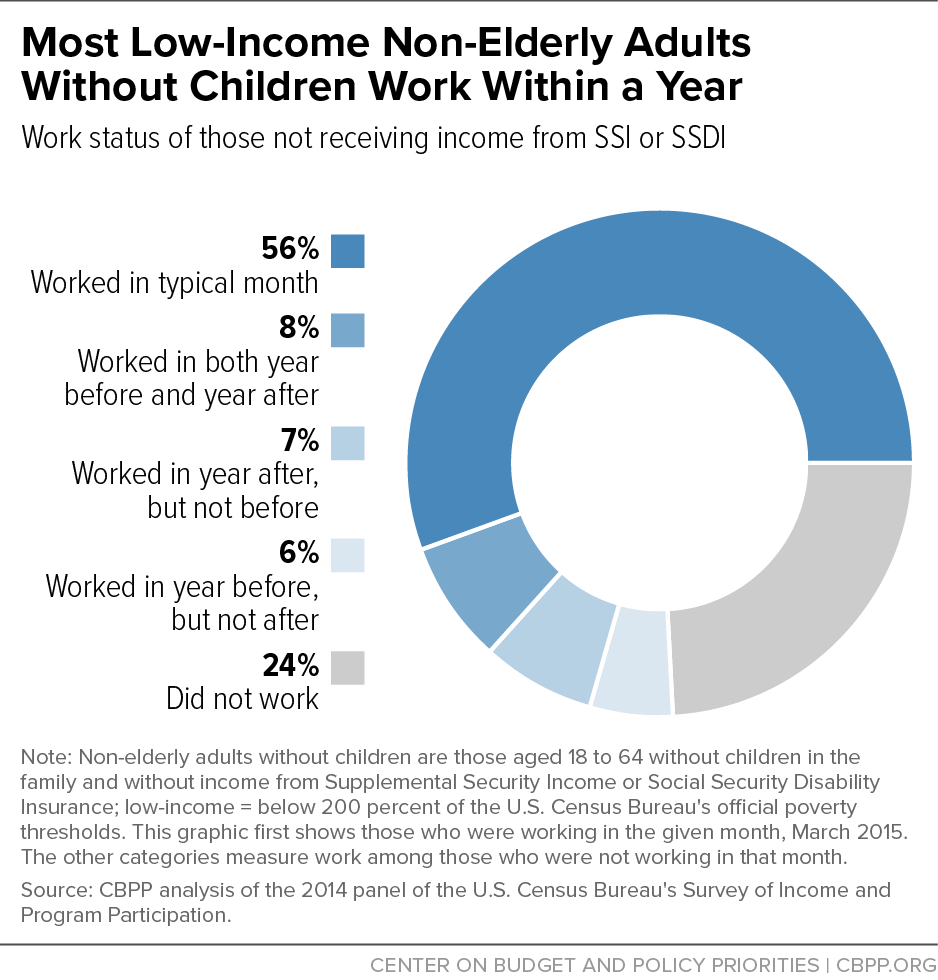

An analysis of work status among low-income, non-elderly adults without children over a period of 25 months using the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP)[12] finds that they have considerable work experience over time, even if many are experiencing joblessness at any given point in time. Among those with incomes below 200 percent of the official poverty line (and receiving no income from SSI or SSDI) in March 2015, 56 percent of these adults worked in that one month, but more than three-quarters (76 percent) worked within the 12 months before or after that month. (See Figure 3.)

Among individuals who were not working during that month, nearly half (46 percent) worked within a year before or after. Those who were not working in that month reported various reasons for their joblessness; more than a quarter (27 percent) noted health reasons as a cause, while 23 percent mentioned school attendance, 22 percent could not find work or were on layoff, and 8 percent reported that they were caring for children or other persons.[13]

Joblessness often reflects challenges such as limited education or disability. Low-income, non-elderly adults without children who had at most a high school diploma or equivalent were less likely than those with a bachelor’s degree or higher to work within a year. And among those not receiving income from SSI or SSDI, individuals who were not working within a year were far more likely to identify as having a core disability and/or a work-related disability[14] than people who did work within that period (54 percent versus 19 percent), illustrating those programs’ strict eligibility criteria and lengthy disability determination processes.

Reflecting the longstanding barriers to employment that people of color face due to racism and discrimination, low-income people of color were somewhat less likely than those identifying as white to work within a year. Despite this difference, at least 67 percent of people in each racial or ethnic group (Black, Latino, Asian, white, or another or multiple races) worked within a year.[15]

Low-income, non-elderly adults without children largely have been left out of the improvements to economic security programs over the last several decades that have been the main sources of progress against poverty for other groups, including non-elderly adults with children, seniors, and those with disabilities, during an era of little wage growth.[16]

Stubborn poverty rates among non-elderly adults without children — their poverty rate was statistically unchanged between 1993 and 2017 — reflect these limited supports. For example:

- Many non-elderly adults without children who are out of work can receive SNAP for only three months while unemployed in any three-year period, a restriction unique to this group.

- They are often uninsured, particularly in the 14 states that have not implemented the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion.[17]

- While TANF is limited for families with children, serving only a small share of poor children, cash assistance for those without children remains even more severely limited — and entirely unavailable in half the states.

- The federal tax code, through both the EITC and the Child Tax Credit, provides considerable support to families with children but offers a meager benefit to those without children and, as a result, some 5 million low-income childless adults are taxed into — or deeper into — poverty.[18]

- And due to limited funding, fewer than 1 in 5 eligible non-elderly adults without children receive any rental assistance, which goes primarily to people with disabilities and seniors.[19]

To provide a full picture of the economic supports available to non-elderly adults without children and comparison groups, this analysis blends the SPM — which counts more forms of income than the “official” poverty measure (among other differences) and therefore more accurately reflects the resources available to low-income families — with corrections for underreporting of key government benefits in survey data.[20]

Our SPM data allow us to see economic security programs’ impact on poverty by calculating the percent of people in poverty two ways: before and after counting government assistance and taxes.[21] The change in poverty between the two calculations shows how effective economic security programs are at reducing the share of people in poverty.

In 1993, before counting government assistance and taxes, 13.5 percent of non-elderly adults without children (and with no income from Social Security or SSI) had income below the SPM poverty line. After counting government assistance and taxes, 12.7 percent of non-elderly adults without children had income below the SPM poverty line — a reduction in poverty of about 6 percent. (See Table 1.)

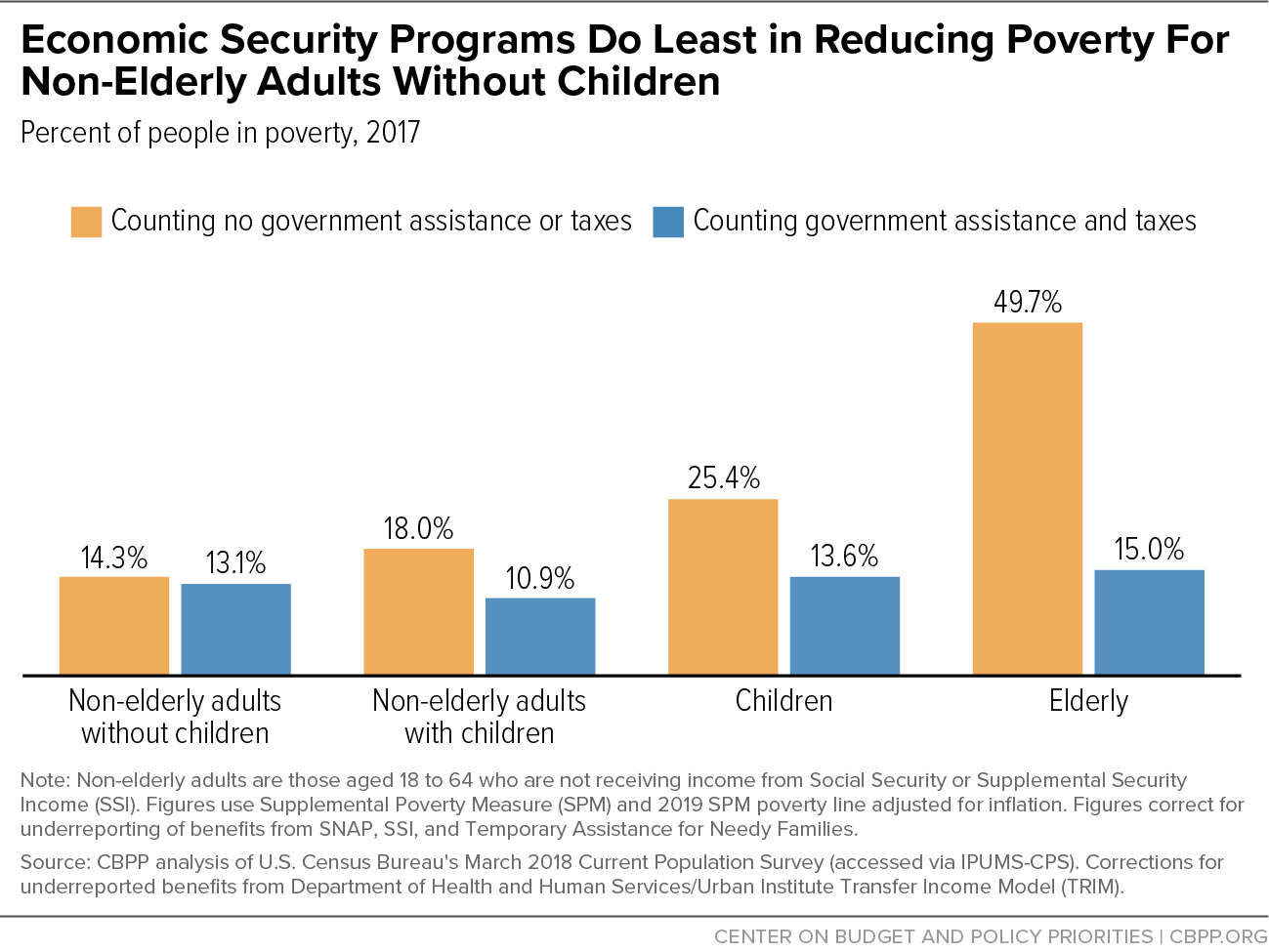

By 2017, the “pre-government” poverty rate for non-elderly adults without children was 14.3 percent while their “post-government” rate was 13.1 percent — a reduction in poverty of about 8 percent, showing that the effectiveness of economic security programs improved only modestly since 1993.[22] (The apparent increase in the poverty rate of non-elderly adults without children from 1993 to 2017 is not statistically significant.)

At the same time, economic security programs became much more effective at reducing the poverty rate for non-elderly adults with children. For these families, government assistance and taxes reduced poverty by 9 percent in 1993, but by 40 percent in 2017. Their poverty rate after counting government assistance and taxes fell by nearly half from 1993 to 2017, from 19.8 percent to 10.9 percent.[23] (See Figure 4.)

One force behind the sharp drop in poverty rates for those with children — but not for those without children — was a major shift in government poverty-reduction efforts that particularly affected families with children, such as improvements in the EITC and the Child Tax Credit.

We see similar results when looking at deep poverty (living with income below half of the SPM poverty line). The deep poverty rate among non-elderly adults without children rose slightly from 1993 to 2017, from 5.0 percent to 5.8 percent, and the effectiveness of economic security programs for this group improved only slightly, with government supports resulting in a 30 percent reduction in deep poverty in 1993 and a 32 percent reduction in deep poverty in 2017. Meanwhile, the deep poverty rate for non-elderly adults with children fell from 4.3 percent to 2.3 percent, as government supports for these families reduced deep poverty by 63 percent in 1993 and 70 percent in 2017.[24]

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Non-elderly adults without children |

Non-elderly adults with children |

Children |

Elderly |

|---|

| 1993 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

13.5% |

21.8% |

31.1% |

57.8% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

12.7% |

19.8% |

26.7% |

20.0% |

| Percent change in poverty |

-6% |

-9% |

-14% |

-65% |

| 2017 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

14.3% |

18.0% |

25.4% |

49.7% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

13.1% |

10.9% |

13.6% |

15.0% |

| Percent change in poverty |

-8% |

-40% |

-46% |

-70% |

| Change: 2017 poverty rate minus 1993 poverty rate |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

0.8% |

-3.7% |

-5.6% |

-8.1% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

0.5% |

-8.9% |

-13.1% |

-5.0% |

For other groups, poverty rates fell significantly over the same period. The poverty rate of children under age 18 was cut nearly in half from 1993 to 2017, from 26.7 percent to 13.6 percent, due in large part to stronger assistance. Unsurprisingly, this is similar to the decline for non-elderly adults with children. (Poverty rates differ slightly for children and the adults who care for them because the average child lives in a larger family than the average adult.) Economic security programs reduced poverty among children dramatically over this period, with government assistance and taxes reducing poverty by 14 percent in 1993 and by 46 percent in 2017.

Poverty also improved for elderly individuals aged 65 and over; from 1993 to 2017, their poverty rate decreased from 20.0 percent to 15.0 percent, and government assistance and taxes in reduced poverty by 65 percent in 1993 and 70 percent in 2017.

Taken together, the figures show that non-elderly adults without children and without income from Social Security or SSI have seen little improvement in their economic security relative to other groups. Unlike other groups, their poverty rate did not fall from 1993 to 2017. And economic security programs reduced their poverty in 2017 far less than for other groups, by just 8 percent, compared to 40 percent for non-elderly adults with children, 46 percent for children, and 70 percent for seniors. (See Table 1 and Figure 5.)

For a complete table of poverty trends, see Appendix Table 2.

Our analysis reflects poverty prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated challenges for low-income individuals. While hardship rates among households with children are higher than those without — likely reflecting the fact that larger households require more income to afford food and face higher costs for housing — low-income, non-elderly adults without children have been hard hit. Many have served as essential workers, while others have lost their jobs, some have struggled to receive unemployment benefits despite eligibility expansions, and many are struggling to make ends meet. Although we lack precisely comparable data on the severity of hardship before and after the start of the pandemic, hardship has clearly risen: nearly 13 percent of non-elderly adults not living with children surveyed from November 25 to December 7, 2020 lived in a household that sometimes or often did not get enough to eat in the last seven days, which was three times higher than the share who said their household didn’t get enough to eat sometimes or often during the entire year in a separate survey from December 2019. (For non-elderly adults living with children, the share in late 2020 was even higher — 18 percent, or five times higher than in the 2019 survey.)a

a CBPP analysis of December 2019 Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement public use file and Household Pulse Survey week 20 public use file.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Overall |

Below SPM poverty line before counting government assistance or taxes |

Below SPM poverty line after counting government assistance and taxes |

Below OPM poverty line |

Below 200% of OPM poverty line |

|---|

| Age |

| 18 to 24 |

16.9% |

25.2% |

26.0% |

27.5% |

27.3% |

| 25 to 34 |

22.6% |

17.8% |

19.1% |

19.9% |

20.8% |

| 35 to 44 |

12.3% |

11.9% |

11.7% |

11.6% |

11.6% |

| 45 to 54 |

21.0% |

18.7% |

18.4% |

17.3% |

17.7% |

| 55 to 64 |

27.3% |

26.3% |

24.8% |

23.6% |

22.5% |

| Sex |

| Male |

52.0% |

51.0% |

51.1% |

49.8% |

50.2% |

| Female |

48.0% |

49.0% |

48.9% |

50.2% |

49.8% |

| Race/ethnicity |

| White only, not Latino |

63.8% |

50.0% |

48.6% |

52.3% |

51.9% |

| Black only, not Latino |

12.3% |

18.9% |

18.2% |

18.9% |

18.1% |

| Latino (any race) |

15.0% |

20.6% |

21.9% |

18.2% |

20.6% |

| Asian only, not Latino |

6.4% |

7.3% |

7.9% |

7.4% |

6.2% |

| Other, not Latino |

2.4% |

3.2% |

3.3% |

3.2% |

3.3% |

| Education |

| Less than high school graduate |

7.0% |

18.0% |

18.1% |

18.4% |

17.2% |

| High school graduate or GED |

27.3% |

36.5% |

36.0% |

34.4% |

35.9% |

| Some college or associate degree |

26.6% |

24.9% |

24.0% |

23.0% |

25.7% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher |

39.1% |

20.6% |

21.9% |

24.3% |

21.3% |

| Full-time student |

9.6% |

17.4% |

18.1% |

21.1% |

16.7% |

| Veteran |

4.6% |

3.8% |

3.1% |

3.7% |

3.4% |

| Disability that limits or prevents work |

5.6% |

14.4% |

12.9% |

16.6% |

12.2% |

| Household size |

| 1 person |

17.2% |

20.1% |

23.4% |

24.6% |

23.4% |

| 2 persons |

47.1% |

39.6% |

38.3% |

43.9% |

44.3% |

| 3 or more persons |

35.7% |

40.3% |

38.4% |

31.4% |

32.4% |

| Married, spouse present |

40.3% |

22.6% |

21.8% |

14.7% |

18.4% |

| Worked at least one week last year |

82.6% |

48.2% |

50.3% |

36.8% |

57.8% |

| Metropolitan status* |

| Metropolitan |

88.2% |

87.2% |

88.6% |

86.6% |

85.8% |

| Non-metropolitan |

11.2% |

12.2% |

10.8% |

12.7% |

13.4% |

| Geography |

| Northeast |

18.2% |

16.7% |

16.3% |

14.8% |

14.6% |

| Midwest |

20.6% |

16.6% |

16.3% |

18.2% |

18.5% |

| South |

37.3% |

41.1% |

41.3% |

42.6% |

42.3% |

| West |

23.9% |

25.7% |

26.2% |

24.4% |

24.5% |

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 |

|---|

| |

Non-elderly adults without children |

Non-elderly adults with children |

|---|

| Age |

| 18 to 24 |

16.9% |

13.9% |

| 25 to 34 |

22.6% |

25.3% |

| 35 to 44 |

12.3% |

33.4% |

| 45 to 54 |

21.0% |

21.1% |

| 55 to 64 |

27.3% |

6.4% |

| Sex |

| Male |

52.0% |

46.5% |

| Female |

48.0% |

53.5% |

| Race/ethnicity |

| White only, not Latino |

63.8% |

54.4% |

| Black only, not Latino |

12.3% |

11.7% |

| Latino (any race) |

15.0% |

23.9% |

| Asian only, not Latino |

6.4% |

7.3% |

| Other, not Latino |

2.4% |

2.7% |

| Education |

| Less than high school graduate |

7.0% |

10.3% |

| High school graduate or GED |

27.3% |

24.7% |

| Some college or associate degree |

26.6% |

26.7% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher |

39.1% |

38.4% |

| Full-time student |

9.6% |

7.8% |

| Veteran |

4.6% |

3.8% |

| Disability that limits or prevents work |

5.6% |

3.3% |

| Household size |

| 1 person |

17.2% |

N/A |

| 2 persons |

47.1% |

3.2% |

| 3 or more persons |

35.7% |

96.8% |

| Married, spouse present |

40.3% |

64.7% |

| Worked at least one week last year |

82.6% |

80.4% |

| Metropolitan status* |

| Metropolitan |

88.2% |

87.4% |

| Non-metropolitan |

11.2% |

11.7% |

| Geography |

| Northeast |

18.2% |

16.6% |

| Midwest |

20.6% |

20.4% |

| South |

37.3% |

37.8% |

| West |

23.9% |

25.3% |

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 |

|---|

| Year |

Children |

Non-elderly adults with children, without income from Social Security or SSI |

Non-elderly adults without children and without income from Social Security or SSI |

Non-elderly adults receiving income from Social Security or SSI |

Elderly |

|---|

| 1993 |

26.7% |

19.8% |

12.7% |

27.2% |

20.0% |

| 1994 |

23.5% |

17.0% |

12.9% |

27.5% |

19.6% |

| 1995 |

21.5% |

15.5% |

12.5% |

26.7% |

18.3% |

| 1996 |

21.2% |

15.4% |

11.9% |

26.4% |

18.1% |

| 1997 |

21.4% |

15.4% |

11.9% |

27.2% |

17.7% |

| 1998 |

20.0% |

14.2% |

10.9% |

26.5% |

16.9% |

| 1999 |

17.9% |

13.0% |

11.0% |

25.8% |

16.0% |

| 2001 |

17.8% |

13.1% |

11.4% |

24.4% |

17.1% |

| 2002 |

17.7% |

13.2% |

11.6% |

24.8% |

17.5% |

| 2003 |

17.4% |

13.0% |

11.7% |

24.2% |

17.7% |

| 2004 |

16.1% |

12.3% |

12.4% |

23.3% |

17.3% |

| 2005 |

16.2% |

12.2% |

12.1% |

23.6% |

17.0% |

| 2006 |

16.5% |

12.8% |

12.2% |

23.7% |

18.1% |

| 2007 |

16.8% |

13.5% |

11.9% |

23.8% |

18.0% |

| 2008 |

16.9% |

13.5% |

12.6% |

22.1% |

17.1% |

| 2009 |

14.3% |

12.0% |

13.5% |

22.4% |

14.8% |

| 2010 |

14.1% |

11.9% |

13.8% |

23.8% |

16.2% |

| 2011 |

14.7% |

12.7% |

14.2% |

24.9% |

15.3% |

| 2012 |

15.2% |

13.3% |

14.6% |

25.6% |

15.6% |

| 2013 |

15.5% |

13.3% |

15.5% |

26.6% |

16.5% |

| 2014 |

15.6% |

13.2% |

15.5% |

26.9% |

16.3% |

| 2015 |

14.5% |

12.2% |

13.7% |

25.7% |

15.0% |

| 2016 |

13.6% |

11.3% |

13.4% |

24.2% |

15.6% |

| 2017 |

13.6% |

10.9% |

13.1% |

23.8% |

15.0% |

| APPENDIX TABLE 4 |

|---|

| Year |

Children |

Non-elderly adults with children, without income from Social Security or SSI |

Non-elderly adults without children and without income from Social Security or SSI |

Non-elderly adults receiving income from Social Security or SSI |

Elderly |

|---|

| 1993 |

14% |

9% |

6% |

56% |

65% |

| 1994 |

20% |

15% |

2% |

54% |

67% |

| 1995 |

25% |

20% |

2% |

55% |

68% |

| 1996 |

24% |

17% |

5% |

56% |

68% |

| 1997 |

20% |

14% |

3% |

57% |

68% |

| 1998 |

22% |

17% |

4% |

56% |

69% |

| 1999 |

25% |

20% |

4% |

56% |

70% |

| 2001 |

23% |

17% |

3% |

59% |

70% |

| 2002 |

26% |

20% |

7% |

59% |

69% |

| 2003 |

29% |

23% |

8% |

60% |

68% |

| 2004 |

32% |

27% |

7% |

61% |

69% |

| 2005 |

32% |

26% |

6% |

61% |

69% |

| 2006 |

31% |

23% |

0% |

60% |

67% |

| 2007 |

31% |

22% |

2% |

61% |

67% |

| 2008 |

36% |

30% |

11% |

64% |

68% |

| 2009 |

52% |

47% |

19% |

66% |

74% |

| 2010 |

53% |

48% |

19% |

64% |

71% |

| 2011 |

51% |

44% |

15% |

63% |

72% |

| 2012 |

50% |

43% |

15% |

62% |

72% |

| 2013 |

47% |

40% |

9% |

61% |

69% |

| 2014 |

46% |

39% |

6% |

59% |

69% |

| 2015 |

48% |

40% |

9% |

60% |

71% |

| 2016 |

48% |

40% |

8% |

62% |

69% |

| 2017 |

46% |

40% |

8% |

62% |

70% |

We examine the characteristics of non-elderly adults without children using the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2018 Current Population Survey (CPS).[25] We define non-elderly adults without children as individuals aged 18 to 64 with no children in their SPM family unit. (Note that based on this definition, non-elderly adults without children could still live in a household that includes children who are not members of their family, or they could be supporting their own children who live in a different household.)

To limit the overall population of non-elderly adults without children to those who are not receiving disability income, we further restrict it to individuals with no personal income from Social Security or SSI. We exclude all Social Security participants, not just those with SSDI, because the CPS did not ask the reason for receiving Social Security in the early years of our analysis. In the March 2018 CPS, half of non-elderly adults without children who are receiving income from Social Security but not from SSI listed disability as their principal reason for receiving Social Security (that is, 4.0 million out of 8.0 million Social Security participants received SSDI). The next most common reason was early retirement.

For characteristics of non-elderly adults with income below the SPM poverty line, before and after counting government assistance and taxes, we use the 2019 SPM poverty line adjusted back in time for inflation (a process known as “anchoring”). We use the 2019 SPM poverty line, as opposed to the 2017 SPM poverty line, for consistency with our poverty trends analysis. (See “Analysis of Poverty Trends” below for more detail.)

The Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Participation (SIPP) is a large-scale, national survey that collects information about household, family, and individual income; program participation; labor force activity; and demographics. It is a longitudinal survey conducted over a multi-year period. Each panel of survey respondents lasts for four years, with each year referred to as a “wave.” Our SIPP analysis is restricted to individuals who are age 18-64, have no children in the family, and do not receive income from SSI or SSDI. We define low income as below 200 percent of the U.S. Census Bureau’s official poverty thresholds.

We examine the employment of low-income, non-elderly adults without children using a survey variable indicating whether a respondent held a job at least one week during the month. We look at employment in a given month of wave 3 of the 2014 SIPP panel (March 2015), and within a 25-month period centered on that month. The estimated percent of low-income, non-elderly adults without children who worked within the 25-month period is not sensitive to the choice of the given month within the 2014 SIPP panel. Across all possible reference months, the estimate ranged from 75 percent to 77 percent.

To be included in this analysis, an individual must be in the SIPP sample universe (civilian, non-institutionalized population) in March 2015 and have a positive SIPP panel weight. The Census Bureau computes panel weights only for people who were in the sample in the first wave and for whom data were reported (or imputed) for each month in the panel for which they were in the SIPP sample universe. This analysis must utilize panel weights because they are the only longitudinal weight that covers the entire period of interest, which spans three waves. An individual must also have provided data for every month in the 25-month period. (An individual who did not provide data for all months may have a positive panel weights if they provided data up until they left the survey due to death or moving to an ineligible address.) Of low-income, non-elderly adults without children in the SIPP sample universe in March 2015, 50 percent have positive panel weights and provided data for every month in the 25-month period.

We create a poverty series by merging data files from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) with historical SPM data produced by the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy.[26] We use the Census Bureau’s SPM data for 2009 through 2017, and the Columbia SPM data for prior years. We correct for underreporting of income from SNAP, SSI, and Aid to Families and Dependent Children/TANF with the Department of Health and Human Services/Urban Institute Transfer Income Model (TRIM). Our poverty series ranges from 1993 to 2017, years for which TRIM data are available. Data for 2000 are omitted due to sample differences between TRIM data and historical SPM data.

For our poverty trends, we define non-elderly adults without children the same way as our analysis of characteristics: Non-elderly adults without children are defined as individuals aged 18 to 64 with no children in their SPM family unit and no personal income from Social Security or SSI. (See “Characteristics of Non-Elderly Adults Without Children” above for more information.)

Our poverty series uses the 2019 SPM poverty line, adjusted in years before for inflation. Using a recent year’s SPM threshold and adjusting it back for inflation creates an “anchored” SPM series.[27] Some analysts prefer it to the standard or “relative” SPM, which allows thresholds to grow slightly faster than inflation as living standards rise across decades. For this analysis, we used an anchored series to ensure that the trends we find are purely due to changes in families’ resources, not changes in the poverty thresholds. We anchored all poverty thresholds to 2019 since it is the latest SPM threshold available.

In our calculations, government assistance includes: Social Security, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, veterans’ benefits, TANF, state General Assistance, SSI, SNAP, the National School Lunch Program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), rental assistance (such as Section 8 and public housing), home energy assistance, the EITC, and the Child Tax Credit. Benefit figures for 2008-2010 also reflect a number of temporary federal benefits enacted in response to the Great Recession: a 2008 stimulus payment, 2009 economic recovery payment, and the 2009-2010 Making Work Pay Tax Credit.