The pandemic and its economic fallout have exposed glaring weaknesses in our nation’s economy that leave millions of people unprotected in bad economic times and prevent them from fully benefiting from a strong economy in good times. The recovery legislation that policymakers will consider later this year (which might consist of one or multiple bills) provides a historic opportunity to build toward an equitable recovery where all children can reach their full potential, where workers in low-paid jobs and those with fewer job prospects have the supports to help them meet their needs and get ahead, and where everyone has access to affordable health coverage. Achieving these goals requires attacking long-standing disparities in our nation, deeply rooted in racism and discrimination, that have led to starkly unequal opportunities and outcomes in education, employment, health, and housing.

The recently enacted American Rescue Plan, along with relief measures enacted in 2020, will provide substantial help during this crisis to tens of millions of people struggling to make ends meet and access health care. But it is important to consider why such large-scale stopgap measures were needed. The reason is clear and sobering: our underlying policies tolerate very high levels of poverty and hardship when households lose jobs or have low incomes, whether this occurs because the economy enters a recession, their employer goes out of business, a family member cannot work due to illness, or the jobs people hold pay low wages. Millions of people face these situations every year, though the impacts of our policy gaps fall disproportionately on people of color.

Indeed, because of the weaknesses in our underlying policies and gaps in our relief measures particularly during 2020, the current crisis has exacted a particularly heavy toll on people working in low-paid jobs and low-income households with children — both groups with disproportionate numbers of people of color. For example, Census Bureau data collected in early February found that nearly 20 percent of households of color with children reported not getting enough to eat sometimes or often in the previous seven days, nearly double the 10 percent figure for non-Latino white households with children (which is also too high).

The Rescue Plan is designed to address the high levels of hardship created by the pandemic and economic crisis. But its measures are temporary, so the considerable progress they will make against poverty, racial disparities, and the number of people lacking health coverage will reverse once they begin to expire unless policymakers invest in measures to create an equitable recovery that allows everyone to share in its benefits.

This nation underinvests in low-income children, tolerates high levels of poverty and economic insecurity, and entered the pandemic with 29 million people lacking health coverage despite enormous progress under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). These investment deficits hold us back as a country and allow gaping disparities to remain — and to widen during a crisis.

Other wealthy nations do far more to invest in children, to support workers and their households both when they are working for low pay and after a job loss, to ensure more adequate minimum wages, and to give everyone access to health care. The United States can afford these kinds of policies as well. Failure to make these kinds of investments and policy changes has real costs, to individuals and the nation as a whole. Research shows that poverty and the hardships that come with it — housing instability, food insecurity, and high levels of family stress that can become toxic to developing children — can have negative long-term impacts on children’s health, education, and earnings. There are negative impacts on adults, as well, when they don’t have enough to eat, face eviction, and don’t have access to health care.

If policymakers don’t take this opportunity to create a more equitable recovery, and craft a legislative package focused only on physical infrastructure and climate technology, future economic growth may be somewhat higher than if no package were enacted at all, but millions of households will see little benefit from that growth.[1] Most people working in low-paid jobs will continue to struggle to make ends meet, those who lose their jobs will not have help to tide them over, tens of millions of people will still lack health coverage, and child poverty and its attendant hardships will remain high, robbing children of the future they deserve.

The American Rescue Plan demonstrates that we have the policy know-how to achieve meaningful advances in these areas. The question is whether we will make the commitment needed for lasting improvements or instead will adopt a “go-small” approach that costs less and achieves far less in charting the course to a more equitable recovery and nation.

This paper outlines recommendations for a recovery package in three areas:

- Investing in children, such as by permanently extending the Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit improvements, expanding rental assistance, investing in good-quality child care and early education, and strengthening the federal food assistance programs.

- Supporting workers and those struggling in the labor market, such as by permanently extending the Rescue Plan’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) expansion for low-paid adults without minor children at home, reforming unemployment insurance, and creating subsidized jobs.

- Expanding health coverage, such as by enhancing financial assistance to help people afford marketplace coverage.

In addition, the recovery package should raise substantial revenue and begin to build toward a more adequate and equitable revenue system that can support the investments necessary to broaden opportunity and improve well-being. After decades of tax cuts, creating such a revenue system will likely take a multi-year effort, and this year represents a historic opportunity to start. But we must not shortchange high-payoff investments in the meantime. Thus the recovery package should include robust revenue measures and responsible health care cost savings, but it should also make critical investments even if some need to be financed over a longer time horizon through borrowing.

Providing stronger, more equitable supports for children — particularly children experiencing financial hardship and disadvantage — can make an important difference in their lives and benefit the nation as a whole. Supports such as income assistance, housing assistance, food assistance, and child care and early education can build opportunity for all children, promoting equity across lines of race, ethnicity, and immigration status and adding to our nation’s collective future prosperity.

Strong evidence links economic support for families with better outcomes for children, ranging from healthier birthweights and lower maternal stress to better academic performance, higher rates of high school graduation and college entry, higher future earnings, and other benefits.

The risks of failing to provide adequate support, on the other hand, are substantial. Even short periods of food insecurity pose long-term health and developmental risks for children. Housing insecurity adds to stress on parents and children and can result in frequent moves that disrupt schooling. Intense financial worries can interfere with parenting, adversely influence children’s mental health and behavior, and in some cases contribute to toxic stress, which is associated with measurable changes in brain structure, cognitive damage, and lifelong health problems such as diabetes and heart disease. As a congressionally chartered report that a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) panel issued in 2019 explained:

The weight of the causal evidence indicates that income poverty itself causes negative child outcomes, especially when it begins in early childhood and/or persists throughout a large share of a child’s life. Many programs that alleviate poverty either directly, by providing income transfers, or indirectly, by providing food, housing, or medical care, have been shown to improve child well-being.[2] [Emphasis added.]

Particularly compelling evidence of the impact of income support comes from a series of cross-program comparisons of several anti-poverty and employment-related pilot programs in the United States and Canada in the 1990s. When programs provided more generous income assistance, they consistently led to better academic performance among young children starting school. Every $1,000 in added annual income brought a significant increase in school achievement relative to peers receiving less generous assistance.[3] Similarly, studies of the introduction of food stamps (later renamed the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP) found that children from disadvantaged families that had access to food stamps in utero or early childhood had better health outcomes as children and adults, were more likely to graduate from high school, and earned more than their peers from counties that had not yet implemented SNAP.[4]

By expanding opportunities for children to thrive, income support programs — including the EITC and Child Tax Credit, which work through the tax code, and SNAP and rental assistance, which are provided in kind rather than in cash — can thus help level the playing field for all children regardless of race, parental education, where they live, and the wide income gaps between rich and poor.

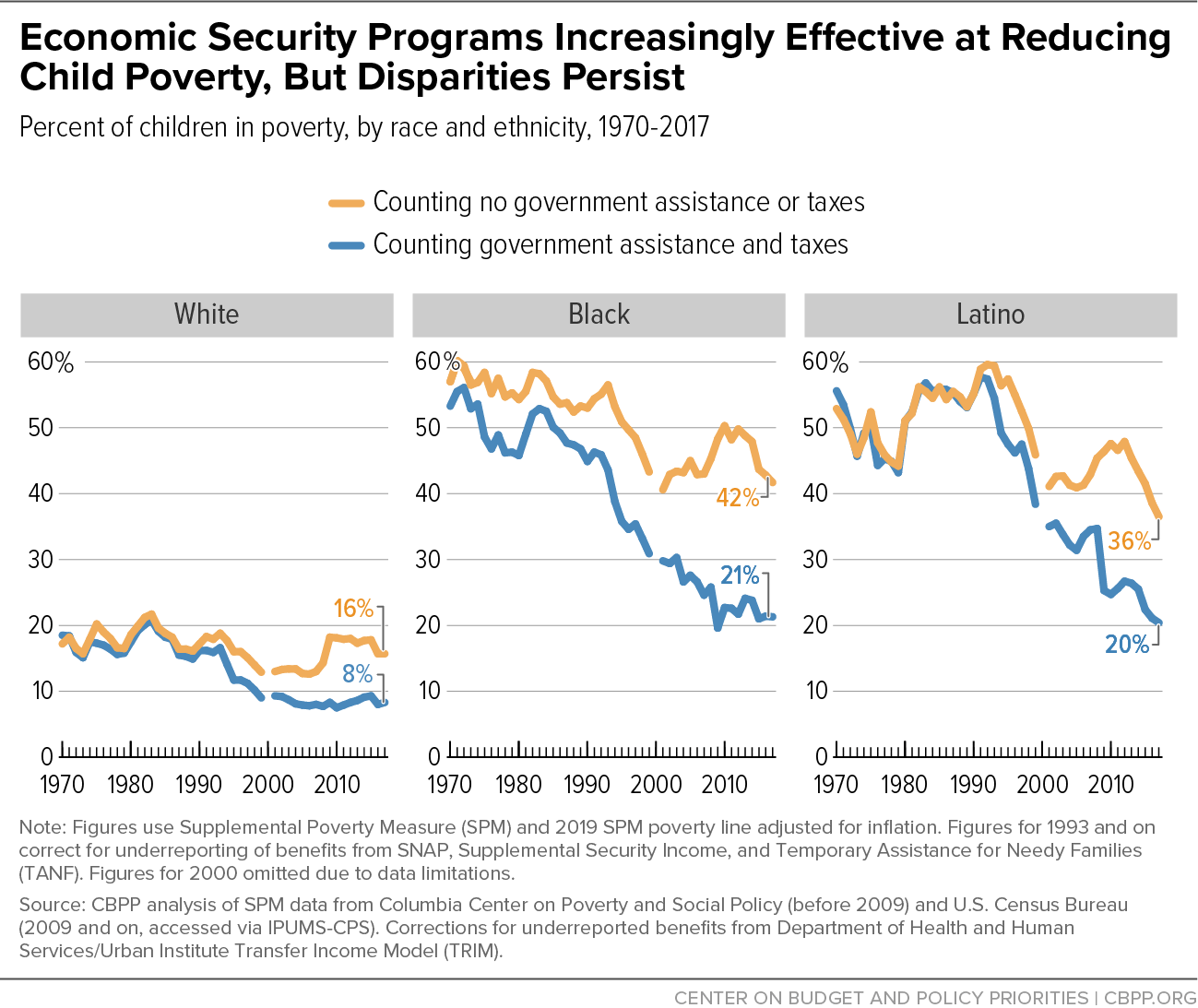

Income support programs have become increasingly effective in recent decades at reducing children’s poverty while narrowing the nation’s long-standing gaps in poverty by race. Between 1970 and 2017, by one measure, poverty rates among Black and Latino children fell by 32 and 35 percentage points, respectively, compared to 10 percentage points for white children. More than half of these declines reflected the increasing poverty-reducing effectiveness of government assistance at lifting families’ incomes above the poverty line. [5] (See Figure 1.)

Poverty remains high, however, especially among Black, Latino, and Indigenous children. Columbia University researchers recently estimated that poverty rates in 2021 will be 9.7 percent for Black children and 9.2 percent for Latino children, compared to just 3.1 percent for white children. These estimates, moreover, account for the Rescue Plan’s assistance for families. Without the Rescue Plan, these groups’ poverty rates would be 21.5, 19.5, and 8.3 percent, respectively, the researchers estimate. Put another way, the Rescue Plan is projected to cut child poverty by more than half for all racial groups this year and shrink racial gaps in child poverty by about half.[6] Official poverty rates are also very high for American Indian and Alaska Native children — similar to those of Black children — but are measured with less precision due to smaller sample size.

Moreover, U.S. anti-poverty policies remain weak by the standards of other wealthy nations. Before factoring in economic security programs, nations such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Nordic countries have poverty rates similar to the United States or even higher. But these countries have lower poverty rates — sometimes much lower — after counting benefits from government programs. Prior to the pandemic, these figures show, our children were poorer than others not so much because U.S. families earn less but because other nations do more when families don’t earn enough to make ends meet.[7]

In addition to income assistance programs, we know that other careful investments in children, such as child care and early education, matter as well. As a Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis analysis explains, “the literature is clear: Dollars invested in ECD [Early Childhood Development] yield extraordinary public returns,” such as fewer years of repeated schooling, higher future earnings, and less crime.[8] Early education appears to have even greater positive effects when high-quality preschool is followed by better-funded K-12 schools. (Similarly, K-12 spending is even more effective at boosting students’ future earnings and other outcomes when preceded by early childhood education.) [9]

A 2020 paper examining causal studies on 133 public policies over the last 50 years finds a “clear and persistent pattern” that investments in children, from birth up to their teen years, consistently yield the largest long-run gains for society of any form of social spending. Many policies for children even pay for themselves in budgetary terms as governments recoup their initial cost through higher tax revenues and lower social spending, say the authors, Harvard economists Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser. Many other investments in childhood may not be self-financing from a narrow budgetary perspective but still add to society’s wealth by advancing future productivity, health, equal opportunity, social cohesion, and other important goals.

The upcoming recovery package should make critical investments in children, including steps to:

Make the American Rescue Plan expansions in the Child Tax Credit permanent. Before the Rescue Plan temporarily expanded the Child Tax Credit, some 27 million children — including roughly half of Black children, half of Latino children, and half of children living in rural areas — received a partial Child Tax Credit or nothing at all because their parents’ earnings were too low or they were out of work during the year. The Rescue Plan makes the full credit available to children in families with little or no earnings in a year and increases the credit’s maximum amount to $3,000 per child ($3,600 for children under age 6). These expansions should become a permanent feature of our tax code. Doing so would keep an estimated 4.1 million children from falling below the poverty level.

Expand housing vouchers toward the goal of ensuring that all households that need rental assistance can receive it. Housing vouchers lower the likelihood that a low-income family lives in crowded housing (by 52 percent) or is homeless (by 74 percent) and reduce their frequency of moving (by 35 percent)[10] — important steps for reducing school disruption and other harmful outcomes for children. But just 1 in 4 eligible households receive any federal rental assistance due to limited funding. Providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line and cut the child poverty rate by one-third, according to a recent Columbia University study.[11] It also would narrow the gap in poverty rates between white and Black households by over a third and the gap between white and Latino households by nearly half.

Well-targeted investments to build or preserve affordable housing are also important, especially in communities with significant housing supply challenges. But supply-side investments often won’t make housing affordable to those most in need unless they are accompanied by vouchers or similar rental assistance, as explained in more detail below.

Invest in good-quality child care and early education. Expanding child care subsidies, increasing the reach of Head Start, Early Head Start, and other high-quality preschool programs, and investing in efforts to boost the quality of care can advance equity and opportunity for children, promote future economic growth, and help make work possible for parents.[12] Investing in the early care and education workforce and boosting their pay would also promote equity for these badly underpaid workers, who are overwhelmingly female and disproportionately women of color, and whose wages average only one-third those of elementary school teachers.[13] (See below for more on expanding child care for working families.)

Strengthen federal food assistance programs to reduce food hardship among children, especially children of color. As noted, the high levels of food hardship emerging in the pandemic highlighted gaps in the federal food assistance programs. Food hardship among low-income children typically rises in the summer, when students do not receive free or reduced-price meals at school. But thanks to the Pandemic EBT program, which has replaced missed school meals during the pandemic and will continue through the coming summer, for the first time low-income children in every state could receive grocery benefits to replace school meals this summer. Adopting this approach every summer could avert periods of food hardship.

Other investments in SNAP, WIC, and the Child Nutrition programs could improve children’s access to food year round. For example, extending the temporary SNAP and WIC benefit increases enacted in COVID relief legislation would ensure adequate benefit levels until the adequacy of the SNAP benefit is studied and adjusted based on evidence of food costs and dietary guidelines (as the Administration has committed to doing pursuant to a provision in the last farm bill) and the Administration updates WIC’s food benefits to reflect science-based recommendations and dietary guidelines. Also, making it easier for schools to enroll low-income students for free school meals automatically and for high-poverty schools to serve meals at no charge to all students under the Community Eligibility Provision would enable low-income children to benefit fully from the school meal programs while targeting federal resources appropriately to those most in need.

The current crisis has highlighted the fact that millions of people who work in jobs essential for society to function receive little pay and limited or no benefits while often facing uncertain hours and scheduling. Many have trouble affording the basics; they often struggle to afford rent, cannot afford decent-quality child care, and lack paid sick or family leave and access to affordable health coverage. For example:

- In 2019 (before the current crisis), 34 million people, including 10 million children, lived in families where someone worked but the family’s earnings were below the poverty line.[14] This included 24 percent of Black children, 23 percent of Latino children, and 8 percent of white children.

- Low-paid workers are less likely to have health coverage through their jobs than better-paid workers. Also, Black and Latino workers are less likely to have employer coverage than white workers; due to structural barriers such as income and wealth inequities, they are disproportionately likely to work in lower-paid jobs, which often don’t come with health benefits. Yet a number of states where people of color disproportionately reside haven’t adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, a key tool to narrow racial and ethnic disparities in health coverage.

- Due to lack of funding, just 1 in 6 children eligible for child care assistance received any, before the temporary investments in child care enacted in response to the current crisis.

- Workers in low-paid jobs and workers of color are less likely to have access to any family and medical leave, paid or unpaid. They also are more likely to have to forgo taking needed time away from work. Low-wage workers are 50 percent more likely to report an unmet need for leave, primarily because they cannot afford to take an unpaid leave.[15]

- Before the American Rescue Plan temporarily expanded the EITC for workers without minor children at home (see below), some 5.8 million such workers were taxed into, or deeper into, poverty, in part because their EITC was too small to offset the other taxes they pay.

- Some 5.7 million working renter households — nearly 1 in 5 — paid more than half their income for housing in 2018. Housing cost burdens this high are linked to lower household spending on other essentials such as food and transportation and higher risk of housing instability.[16]

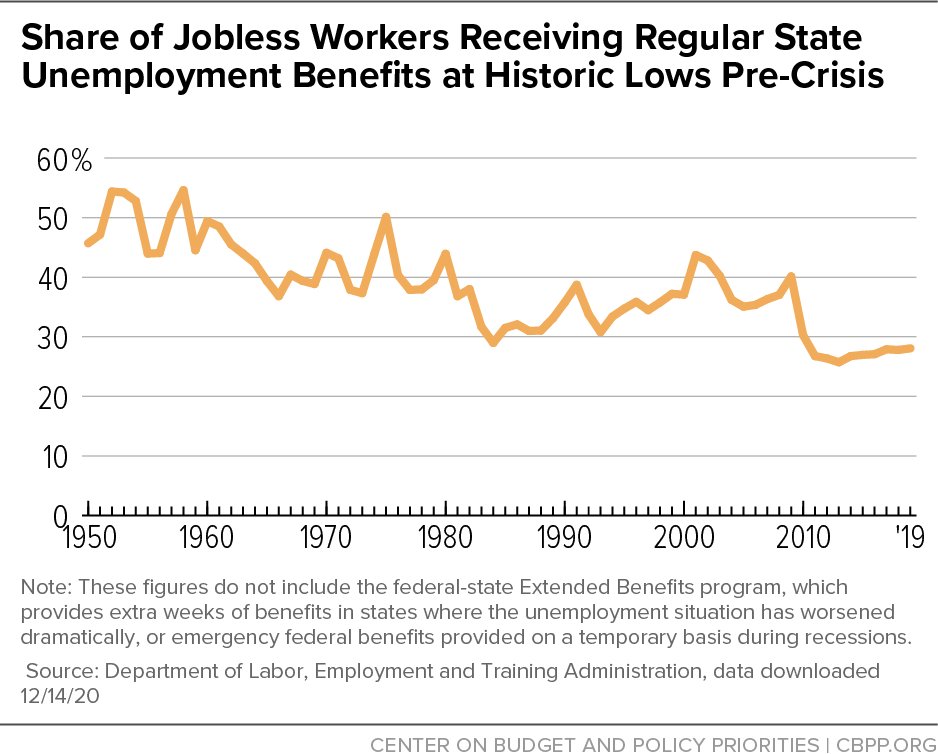

Moreover, workers often get little help when they lose their job or are out of work. Prior to enactment of temporary relief measures during the current crisis, the unemployment insurance (UI) system did not work well for those who lost a low-paid job. States have considerable discretion over UI benefit levels, eligibility criteria, and duration of benefits, and changes to state UI laws after the Great Recession made it harder for jobless workers to navigate the application process and to document and maintain eligibility; some states also cut the maximum number of weeks of benefits. In addition, many states maintained outdated eligibility criteria that exclude people such as unemployed workers looking for part-time work and those who leave work for compelling family reasons, like caring for an ill family member.

As a result, the share of unemployed workers receiving UI prior to the pandemic ranged from 57 percent in Massachusetts down to 11 percent in Arizona, Florida, and Louisiana; 10 percent in Nebraska, North Carolina, and South Dakota; and 9 percent in Mississippi.[17] Some of the decline in UI recipiency prior to the current crisis reflected states’ failure to modernize their UI systems to meet the needs of a 21st century economy, but the National Employment Law Project concluded that “it is clear that some states have engaged in conscious strategies to decrease recipiency.”[18]

The bottom line is that on the eve of the pandemic, a large share of low-paid workers — a disproportionate number of whom are women and people of color — didn’t qualify for any unemployment benefits if they lost a job or didn’t bother applying because states had made the system so hard to access. (See Figure 2.) For those who did qualify, benefits in many states were very low. Benefits just prior to the current crisis averaged $387 a week nationwide but less than $275 in the ten lowest-paying states, and low-paid workers generally received much less than the average. (UI benefit amounts are tied to workers’ previous wages.) At the same time, many workers without minor children at home who lost their job or whose work hours dropped below 20 a week faced a three-month time limit on receiving food assistance through SNAP.

During the current crisis, federal policymakers enacted measures to address these deficiencies temporarily. They shored up the unemployment system by expanding eligibility and increasing benefit amounts and durations. They also suspended the SNAP three-month limit to improve access to food assistance regardless of employment status. But absent these kinds of measures, even the temporary loss of a low-paying job can cause immediate financial difficulties for a household.

To be sure, the EITC for families with children and SNAP benefits help millions of households with low earnings make ends meet. And in states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, many low-paid workers can access comprehensive coverage through Medicaid. But as the data above show, people working in low-paid jobs can face severe economic insecurity.

Raising the minimum wage is a key part of better supporting workers; an adequate minimum wage is critical to helping workers in low-paid jobs and their households make ends meet. But that’s not enough. The recovery package should include critical investments that would markedly improve economic security for those working in low-paid jobs and those struggling to find jobs, including the following:

Make permanent the American Rescue Plan’s EITC expansion for low-paid adults without minor children at home. The Rescue Plan temporarily raises the maximum credit for these adults from about $540 to about $1,500, expands eligibility to include younger adults aged 19-24 (excluding students under 24 attending school at least part time) and people aged 65 and over, and raises the income limit to qualify from about $16,000 to at least $21,000. Over 17 million low-paid working adults will benefit from these changes. The recovery package should make them permanent.

Reform unemployment insurance. To ensure that workers have access to unemployment benefits when they need them, the recovery package should require states to set the maximum number of available weeks at 26 or higher, set a floor on benefit levels to ensure that they are adequate for low-paid workers, and modernize their eligibility criteria (including permitting good-cause reasons for leaving a job, such as illness or a family emergency, and counting workers’ recent work history in determining their eligibility and benefit levels). It also should modernize the permanent Extended Benefits program so that additional weeks of benefits turn on quickly in a recession and do not turn off while a state’s unemployment is still high; these steps would improve UI’s “automatic stabilizer” properties and support lower-paid workers when jobs are harder to find. Finally, the package should take a first step toward addressing UI financing by increasing the federal taxable wage base, which establishes the minimum state taxable wage base; it has been set at $7,000 per employee since the early 1980s.

Expand child care assistance to enable parents to work. Child care is expensive: center-based care for a toddler cost $910 per month on average in 2018, and infant care cost substantially more.[19] For a mother who is paid $12 an hour for 30 hours of work per week, earning $1,550 per month, child care for one child would eat up more than half of her income. Yet only a small fraction of those eligible for child care assistance receive it, and families often make do with less stable child care arrangements. Parents often lose their jobs when child care arrangements fall through.

Create a national paid leave program. Paid family and medical leave is important not only during a crisis but also in everyday circumstances, when workers need to take time off from work due to illness or caregiving responsibilities. Paid leave was a critical missing piece of this nation’s care infrastructure when the pandemic hit — particularly for women and people of color, who more often work in jobs without these benefits and whose lower earnings make it harder for them to take unpaid leave. (Moreover, women often take on a larger caregiving role in many families.) The recovery package should include a broad-based, comprehensive, progressive paid family and medical leave policy.

Expand housing vouchers and invest in renovating and building affordable housing. As the economy recovers, high housing costs will continue to create economic instability and hardship for millions of low-income renters, increasing their risks of housing instability and homelessness and undercutting their children’s chances of succeeding over the long term. Housing vouchers make rent affordable for people in low-paying jobs and are highly effective at reducing homelessness, as noted above. They also serve as an important hedge against housing instability and financial hardship during recessions because the voucher subsidy rises when a household’s income falls due to loss of a job or work hours.

Investments in renovating and building affordable housing also have an important role to play, particularly in tight housing markets. Carefully designed investments of this type can make rents more affordable for low-income families, reduce homelessness, improve residents’ living conditions and health outcomes, and reduce racial inequities in housing opportunities and housing quality. They also generate jobs and construction activity and can lower greenhouse-gas emissions by making developments more energy efficient. In making such investments, policymakers should place a high priority on renovating the existing public housing stock, creating housing options for people experiencing homelessness, and providing substantial additional resources for affordable housing development through the Indian Housing Block Grant and National Housing Trust Fund.

However, supply interventions alone will not address the affordable housing crisis. Many communities have ample supply of housing but housing remains unaffordable for people with modest incomes. Additionally, supply interventions often do not produce housing with rents that are low enough to be affordable for households with incomes near or below the poverty line — the group that makes up most of the renters confronting severe housing affordability challenges[20] — unless those households also receive a voucher or similar rental assistance. Voucher expansion is therefore crucial to ensuring that a recovery package reaches those who most need help to afford stable housing.

Invest in workforce development and create subsidized jobs. As the economy recovers, some workers and new entrants to the labor market will continue to face challenges finding jobs for longer periods. Historically, Black workers have experienced very high unemployment rates in the best of times and devastatingly high rates in recessions and slow recoveries. Fully six years after the Great Recession technically ended, for example, unemployment still stood at 9.9 percent for Black workers in the second quarter of 2015, compared to 4.7 percent for white workers. Creating an equitable recovery will require new investments in training for in-demand quality jobs, career navigation for those looking to enter new fields, and subsidized jobs for those unable to find work.[21] These investments can provide pathways forward to those who would otherwise be left out of the recovery.

Eliminate the SNAP three-month time limit so those out of work can afford food. Adults without a disability who are aged 18-49, not raising children at home, and not employed or in training 20 hours per week can receive only three months of SNAP benefits out of every three years, unless the requirement is waived in a community because of economic conditions. (The requirement is currently waived nationally during the public health emergency.) But many adults, especially those without a college education, face serious labor-market challenges and even in good times may struggle to find new stable employment in just three months. And, evidence shows that many individuals who should meet exemption criteria nonetheless lose food assistance because of the time limit. The recovery package should eliminate the time limit permanently to ensure that when people are out of work, they can afford to eat.

Expanding Health Coverage

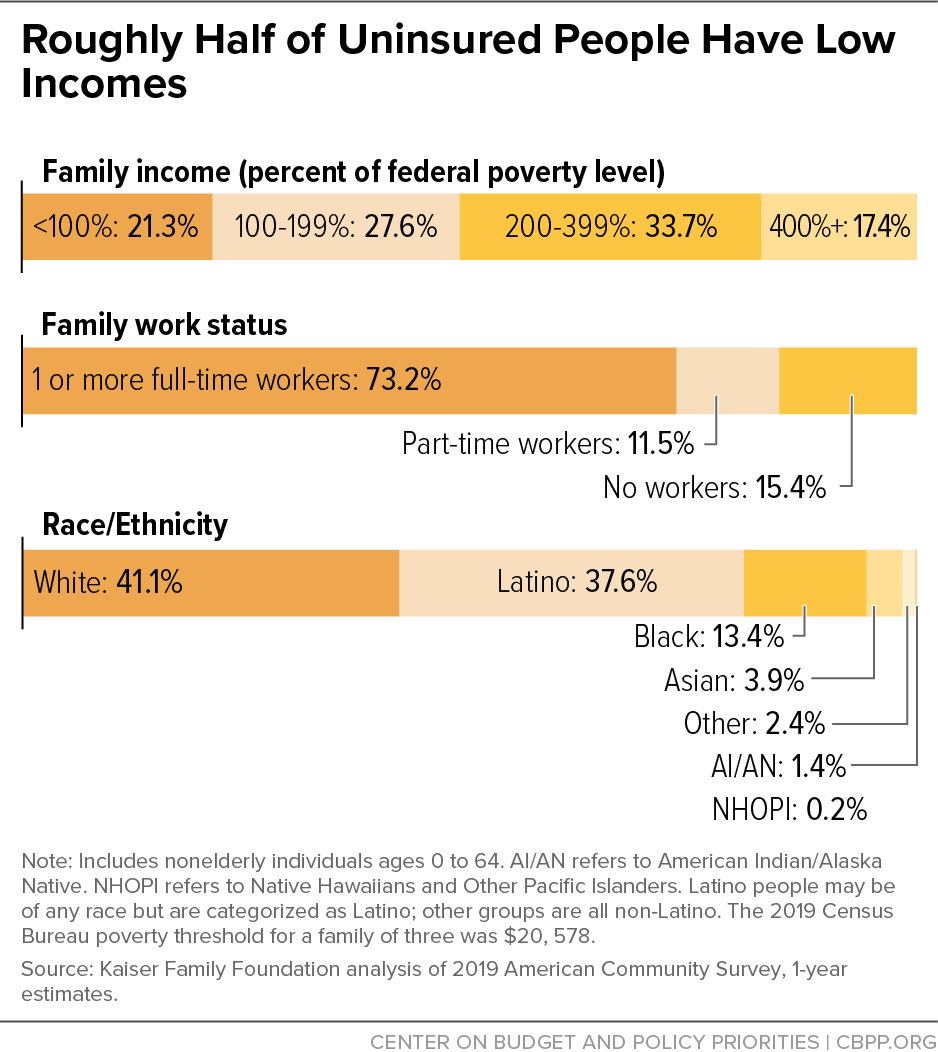

The ACA cut the nation’s uninsured rate nearly in half, from 16 to 9 percent.[22] This historic achievement led to improvements in health care access, financial security, and health outcomes — including reductions in premature deaths[23] — and narrowed racial gaps in coverage and access to care, especially between Black and white people.[24] But the 29 million people who remain uninsured have not shared in these benefits. This group tends to have low incomes, and 56 percent of them are Latino, Black, or other people of color, according to Census data. (See Figure 3.)

Many low-wage jobs either don’t offer health coverage or offer coverage that’s unaffordable. Strengthening Medicaid and subsidized marketplace coverage should be an important part of a recovery package that strives to make the economy work better for everyone, promote health, and narrow racial and ethnic disparities, including in health care.

By making health care more accessible and affordable for a broader swath of people we could ensure that the recovery improves their health, well-being, and economic security. We must also ensure that all people eligible for Medicaid can get covered and make it easier for people to maintain coverage once they have it.

Indeed, expanding Medicaid is critical to achieving an equitable recovery. If the 14 states that have not expanded Medicaid did so, nearly 4 million uninsured low-income adults could gain coverage. People of color would disproportionately benefit: 29 percent of the uninsured people who would gain Medicaid eligibility are Latino and 23 percent are Black, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates.[25] The American Rescue Plan included strong new incentives — on top of those already in place — that hopefully will prod additional states to expand Medicaid.[26]

The recovery package should also:

Enhance financial assistance in the marketplaces. A major reason why millions of people, especially those with low incomes, remain uninsured is that they cannot afford coverage. Reducing net premiums increases coverage significantly, research shows.[27] For example, Massachusetts ― which has the nation’s lowest uninsured rate for people with incomes between 138 and 250 percent of the poverty line ― provides sizable state subsidies on top of those the ACA offers, greatly reducing premiums for people with income below 300 percent of poverty.

The recovery package should build on the American Rescue Plan’s temporary increases in marketplace premium tax credits by permanently increasing premium credits and cost-sharing assistance to ensure that people with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line pay $0 premiums for a plan with reduced deductibles and other cost sharing. It also should boost financial help with premiums, deductibles, and other cost sharing for people with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of poverty. And it should continue the Rescue Plan provision that eliminates the premium tax credit “cliff” of 400 percent of poverty, so that people with incomes above that level who face a high premium burden can get help affording coverage.

Eliminate or lower the ACA “firewall.” About 2.7 million uninsured workers and family members with incomes below 400 percent of poverty are ineligible for subsidized marketplace coverage due to the “firewall,” which makes people who have an offer of employer-sponsored coverage ineligible for marketplace financial assistance if the employer coverage meets minimum federal standards for affordability and comprehensiveness. The standards are insufficient, barring many low-income people from enrolling in subsidized marketplace coverage that would be far more affordable and comprehensive.[28] Eliminating the firewall would give workers a choice of employer coverage or subsidized marketplace coverage.

Alternatively, policymakers could allow family members to enroll in subsidized coverage if the cost of employer family coverage is above the affordability threshold; this is sometimes described as fixing the “family glitch.” They also could lower the affordability threshold (9.83 percent of income in 2021) used to determine whether an employer coverage offer is affordable.

Reduce Medicaid “churn” through continuous eligibility. Many people exit Medicaid because their incomes rise modestly over program limits or they fail to return needed paperwork, only to regain eligibility within months. Often, individuals lose coverage even though they remain eligible. This “churn” disrupts access to medication and other care and is burdensome for states and health plans. About half the states have taken up Medicaid’s continuous eligibility option, which enables them to allow children to remain eligible for 12 months at a time. New York and Montana provide continuous eligibility for adults through a Medicaid demonstration project. The recovery package should require all states to implement continuous eligibility for children and adults, or as an alternative, require it for children and create a state option for adults.

Provide continuity of care for people leaving jail or prison. Many people go without needed health care while incarcerated, leave jail or prison without adequate access to medications, or don’t get needed health care when they are back in the community. These gaps in care contribute to a litany of poor health outcomes — especially for Black and Latino people, who are incarcerated at higher rates — and thus make recidivism more likely. The recovery package should allow states to receive a federal match for Medicaid services provided to people during their last 30 days in prison or jail.

Broaden the availability of home- and community-based services. To ensure that everyone who needs these services can receive ongoing, reliable, quality care, we must expand the caregiving workforce. That, in turn, will require better training and working conditions and higher pay, and the increased costs will be passed on to state Medicaid programs. The recovery package should provide states with additional funding to accommodate them.

Provide adequate, stable Medicaid funding for Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories. Unlike the states, Puerto Rico and the other territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) receive Medicaid funds through a fixed, inadequate block grant and a 55 percent federal matching rate that is unrelated to need. Temporary increases in the territories’ allotments and matching rates expire at the end of September 2021. The recovery package should include a permanent fix giving the territories stable, adequate funding and putting them on a path to align their Medicaid programs with the program that operates in the states as quickly and completely as possible.

Strengthen Medicaid’s response to future economic downturns. The recovery package should establish a permanent mechanism to raise the federal share of state Medicaid costs when a state’s unemployment rate is above normal levels, which would enable states to receive increased Medicaid funding in a recession without additional congressional action. Proposals with this structure have been introduced in the House, including as part of a House Democratic COVID relief proposal in 2020 (H.R. 6379), and in the Senate, in a bill with 19 sponsors and cosponsors (S. 4108).

Preferably, policymakers would finance the investments needed to help all children thrive, support workers and those with limited job options, and expand health coverage through higher revenues and responsible health care savings. All else being equal, less debt is better for the economy, though many economists in recent years have concluded that the nation can safely hold more debt than previously thought desirable.[29] And, as discussed below, there is plenty of room to raise revenues in a progressive manner: our pursuit in recent decades of ever-lower taxes, especially on wealthy households, has severely weakened our ability to invest in critical priorities. Moreover, raising more revenues in a progressive manner and investing the revenues in ways that improve economic opportunity can push back on racial disparities, as can overhauling regressive or unproductive tax breaks and giving IRS the resources it needs to collect all of the taxes that are owed.[30]

However, creating a stronger, more sustainable tax structure that raises adequate revenues will likely take time and require more than one piece of legislation. So while we should finance as much of these high-priority investments as possible with revenues and health care cost savings, we should not “go small” on investments. Given the urgent need to build an equitable recovery, the high return on investment of many of these policies, and today’s low interest rates, the nation stands to gain far more by deficit-financing some of these investments than by jettisoning them if the offsets immediately available fall short of the total investment needs. There is a particularly strong argument for using deficit financing, which allows the cost of an investment to be stretched out over a long time horizon, for investments whose benefits similarly accrue over many decades.

In 2000, after a strong economic recovery and net tax increases over the previous decade, federal revenues equaled 20 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). Yet total U.S. revenues were still well below revenue levels in other wealthy countries with more robust public investments.[31]

Two decades and two large regressive tax cut packages later, and at the same point in the business cycle, that ratio of revenue to GDP had fallen to 16.3 percent in 2019 — far too low to support the kinds of investments needed for a 21st century economy that broadens opportunity, supports workers, and ensures health care for everyone. . In 2019, the difference between revenues at 20 percent of GDP and 16.3 percent was about $785 billion. Simply restoring a significant fraction of this revenue loss could raise trillions of dollars over the next decade for investments to make the economy stronger and work better for everyone. More will ultimately be needed to address health care and retirement costs as well over the long run.[32]

Asking the wealthiest people in the country — a group whose wealth soared in the two decades prior to 2000, rose further during the two decades since 2000, and is now at a record high despite the global pandemic[33] — to pay more would be a good place to start. Very wealthy households do not pay taxes annually on a large share of their income and often can avoid paying taxes on much of the appreciation of their assets throughout their lifetimes, even as middle-income people pay taxes on their earnings.[34] And, because of the way in which wealth is shielded from taxation at death, a substantial share of wealth accumulation is never taxed.[35]

When wealthy people do pay tax on the income from wealth, it is often at special, discounted rates. The tax cuts enacted under President George W. Bush created or expanded several tax advantages for income from wealth. For example, dividends are no longer taxed at the same rate as wages, as they had been for much of the previous century. The 2017 Trump tax cuts continued the drive to reduce taxes on very large inheritances, doubling the amount of an estate that is entirely free of estate tax to $22 million per couple. And some wealthy individuals can use additional asset-protection mechanisms to further shield estates above this exemption level from taxation.

In addition, the 2017 Trump tax cuts slashed the corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, well below the level needed to compete with other nations, the common justification for the change. They set the tax rate on foreign profits of U.S.-based multinationals even lower, which means that companies continue to have sizable incentives to shift profits — and investments — out of the country to reduce their tax bills.

This drive toward lower effective tax rates on wealthy people and profitable corporations has led both to greater inequality and to underinvestment in areas that promote broadly shared economic growth, widen opportunity, and improve well-being among those not already well heeled.

Any effort to raise additional revenues should also focus on the roughly half-trillion dollars of taxes that are owed annually under current law but go uncollected. The IRS enforcement budget has been cut a quarter since 2010 and the number of revenue agents — auditors who are uniquely qualified to process the complex returns of high-income individuals and corporations — has fallen by 39 percent.[36] Audit rates have plummeted. For example, the audit rate on millionaires has fallen by a jaw-dropping 71 percent over the same period, from 8.4 percent to just 2.4 percent.[37] Rebuilding the IRS enforcement division should be a key component of any recovery legislation. There is broad consensus that every additional dollar spent on enforcement generates multiple dollars in revenues.

Creating a more adequate and equitable revenue system will likely take a multi-year effort, and this year represents an historic opportunity to start. The package should include robust revenue increases, but we must not shortchange high-payoff investments if revenue increases must be done in several stages. Investments in infrastructure and climate technologies, children, workers, and health care are badly needed now and will address glaring racial disparities, improve health, and allow more children to reach their full potential.