The 35 states (plus the District of Columbia) that have implemented the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion are better positioned to respond to the COVID-19 public health emergency and to prevent the ensuing economic downturn from worsening access to care, financial security, health outcomes, and health disparities. The 15 remaining states should act swiftly to implement expansion to help their residents weather the crisis.

Expansion states entered the crisis with much lower uninsured rates than non-expansion states, due in large part to expansion. That’s important for public health because people who are uninsured may forgo testing or treatment for COVID-19 due to concerns that they cannot afford it, endangering their health while slowing detection of the virus’ spread. Expansion — which provides coverage to non-elderly adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line (about $17,600 for a single adult) — has given Medicaid coverage to over 12 million people. At least 4 million uninsured adults would become eligible for Medicaid coverage if the remaining states expanded, a number likely to increase due to the recession.

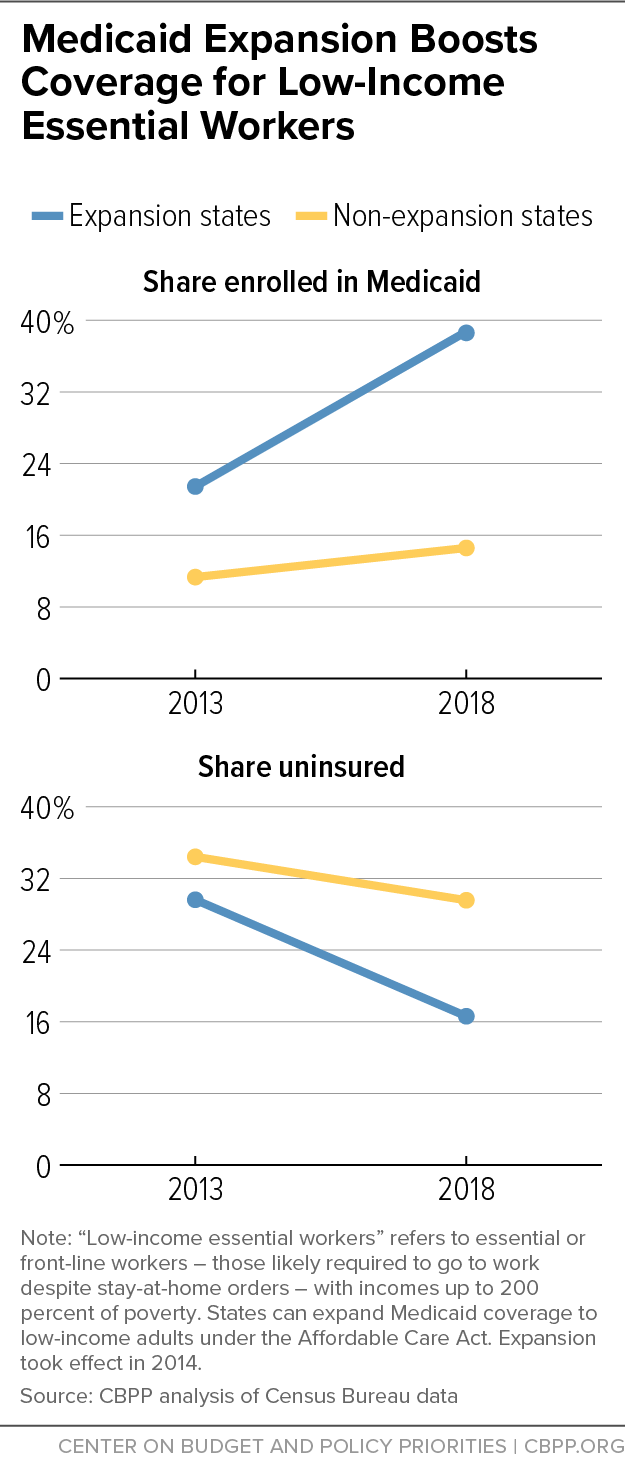

Many people who could gain coverage through expansion are those at elevated risk from the virus, whether because they face a high risk of becoming infected or a high risk of serious illness if they do. Expanding Medicaid in the remaining states could cover 650,000 currently uninsured “essential or front-line workers” — those who have jobs that likely require them to show up for work regardless of stay-at-home orders or other restrictions, such as hospital workers, home health aides, and grocery store workers. Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, the uninsured rate for low-income workers in these jobs was 30 percent in non-expansion states, nearly double the rate in expansion states. (See Figure 1.) Expanding Medicaid in the remaining states would also provide coverage to millions of older adults, people with disabilities, and others with underlying health conditions that increase their risk of complications from the disease. (See Appendix 1 for estimates by state.)

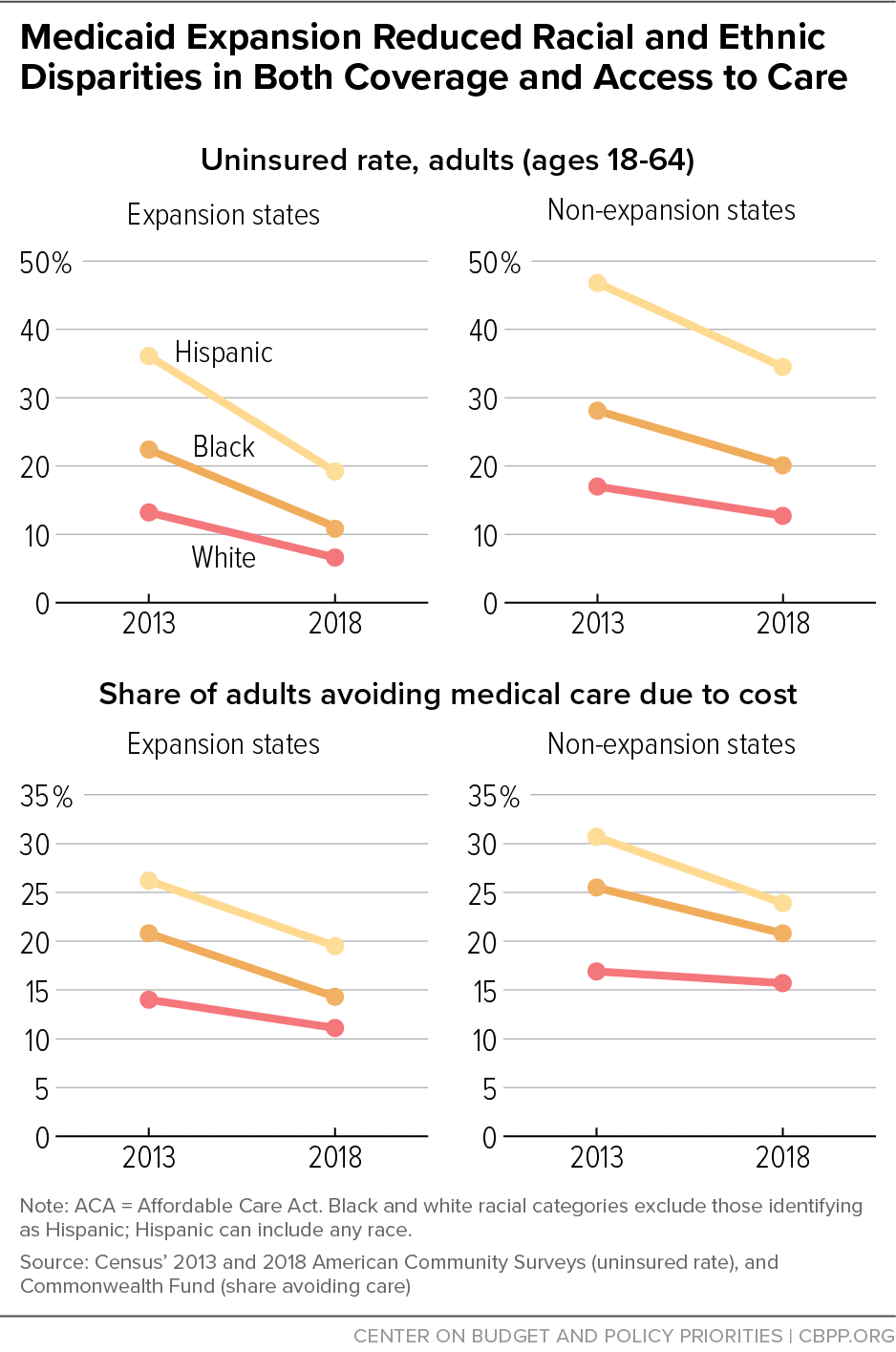

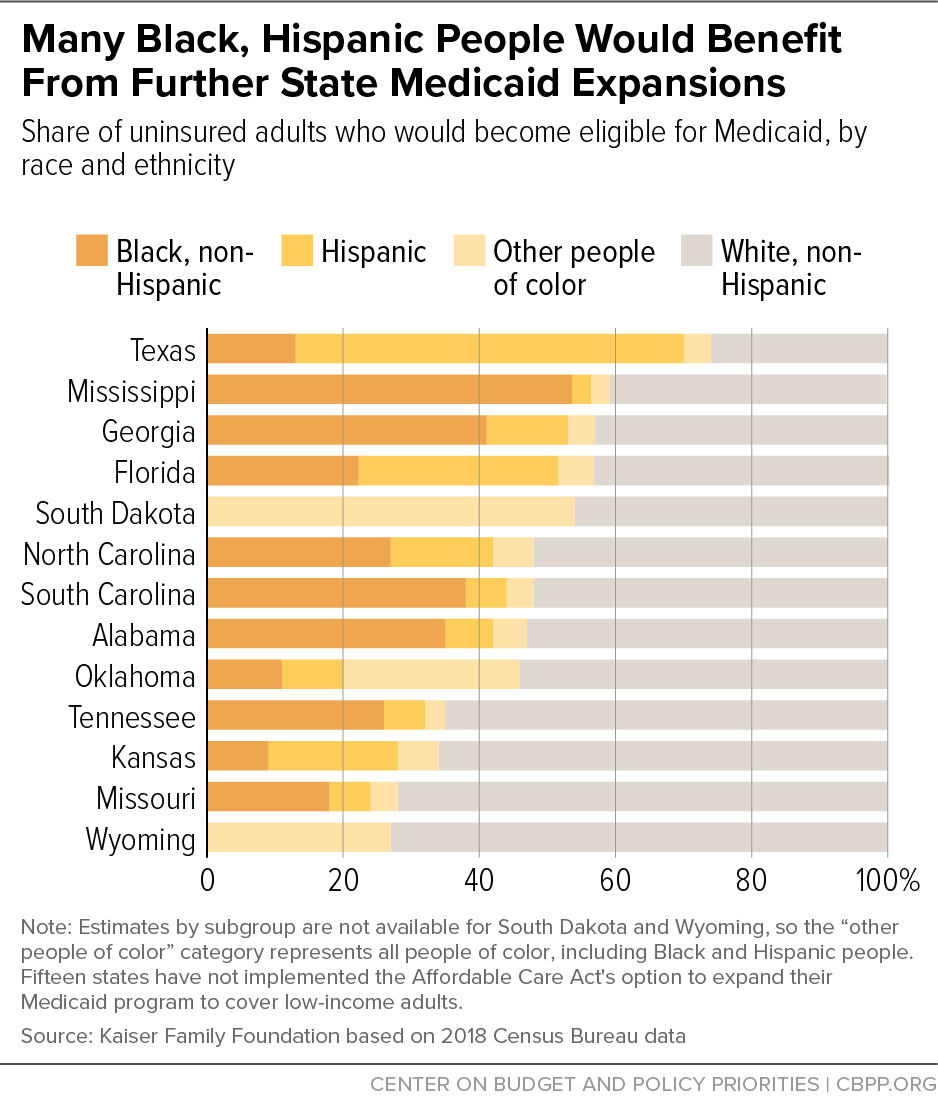

Expansion has also helped narrow racial and ethnic disparities in both health coverage and access to care. That puts expansion states in a better position to respond to the higher COVID-19 infection and mortality rates that Black and Hispanic people and American Indians and Alaska Natives are experiencing in many places; nationwide, for example, the mortality rate for Black people is more than twice as high as most other groups. Expansion does not eliminate these disparities, which are tied to longstanding racial, economic, and health system inequities, but it does allow people to access treatment for COVID-19, as well as for underlying health conditions that may worsen its effects. If the remaining states expanded, the majority of the uninsured people gaining Medicaid eligibility would be people of color. In particular, Black people would comprise 23 percent of those gaining eligibility and Hispanic people would comprise 29 percent, according to Kaiser Family Foundation estimates.

Medicaid expansion can also help prevent the recession from increasing uninsured rates and thereby worsening access to care, financial hardship, health outcomes, and health disparities. Already, as many as 27 million people may have lost job-based health coverage as a result of the recession, Kaiser Family Foundation researchers estimate. Urban Institute researchers project that 40 percent of people losing job-based coverage in non-expansion states will become uninsured, compared to 23 percent in expansion states, largely because fewer will qualify for Medicaid. By providing health coverage for people who lose their jobs or experience sharp drops in income, expansion can also help prevent this recession from widening racial gaps in access to coverage and care, as the Great Recession did.

Since the federal government pays 90 percent of the cost of expansion, increased Medicaid coverage comes at little upfront cost to states, even if more people need coverage because of the recession. Moreover, many states have seen offsetting savings from expansion, for example due to reduced uncompensated care costs for public hospitals, reduced costs for safety net health programs (especially behavioral health), and increased revenue from taxes on providers and managed care plans. Since the recession will increase uninsured rates, uncompensated care costs, and costs for safety net health programs, expansion’s offsetting savings will grow along with its gross costs. And the billions of dollars in additional federal funds that will flow to expansion states will provide valuable fiscal stimulus that will help preserve jobs.

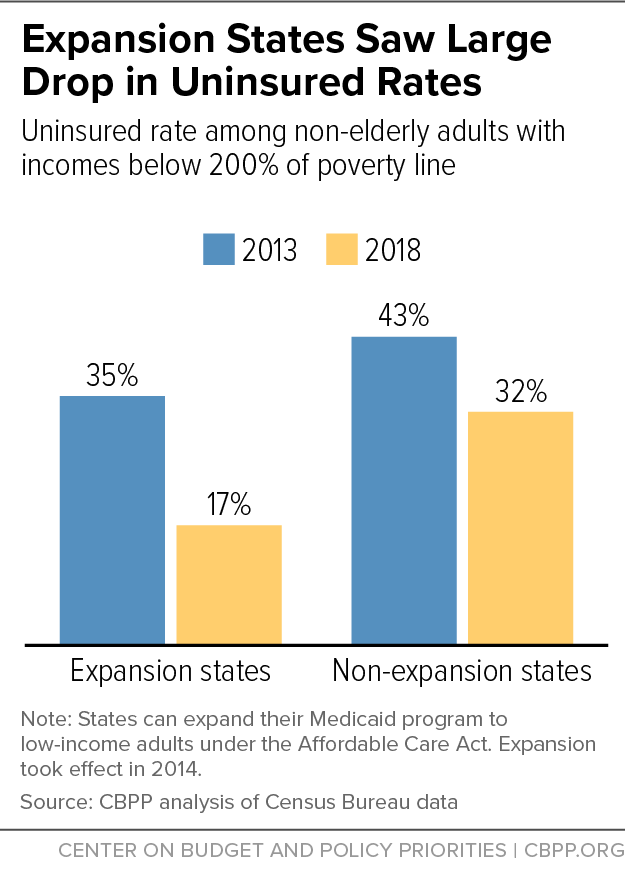

While all states have seen uninsured rates fall since the ACA’s major coverage provisions took effect in 2014, states that expanded Medicaid have made the greatest progress in increasing health coverage. In 2018 the uninsured rate among low-income, non-elderly adults in expansion states was 17 percent, compared to 32 percent in non-expansion states, a 52 percent versus a 24 percent decline from 2013. (See Figure 2.)[1] Prior to the onset of the pandemic and recession, over 12 million newly eligible people had health coverage through the Medicaid expansion. Another 4 million uninsured people would gain eligibility for Medicaid coverage if all states expanded. (For an explanation of this and other estimates, see Appendix 1. Estimates for non-expansion states include Nebraska and Oklahoma, where voters have passed initiatives adopting expansion, but it has not yet been implemented.)

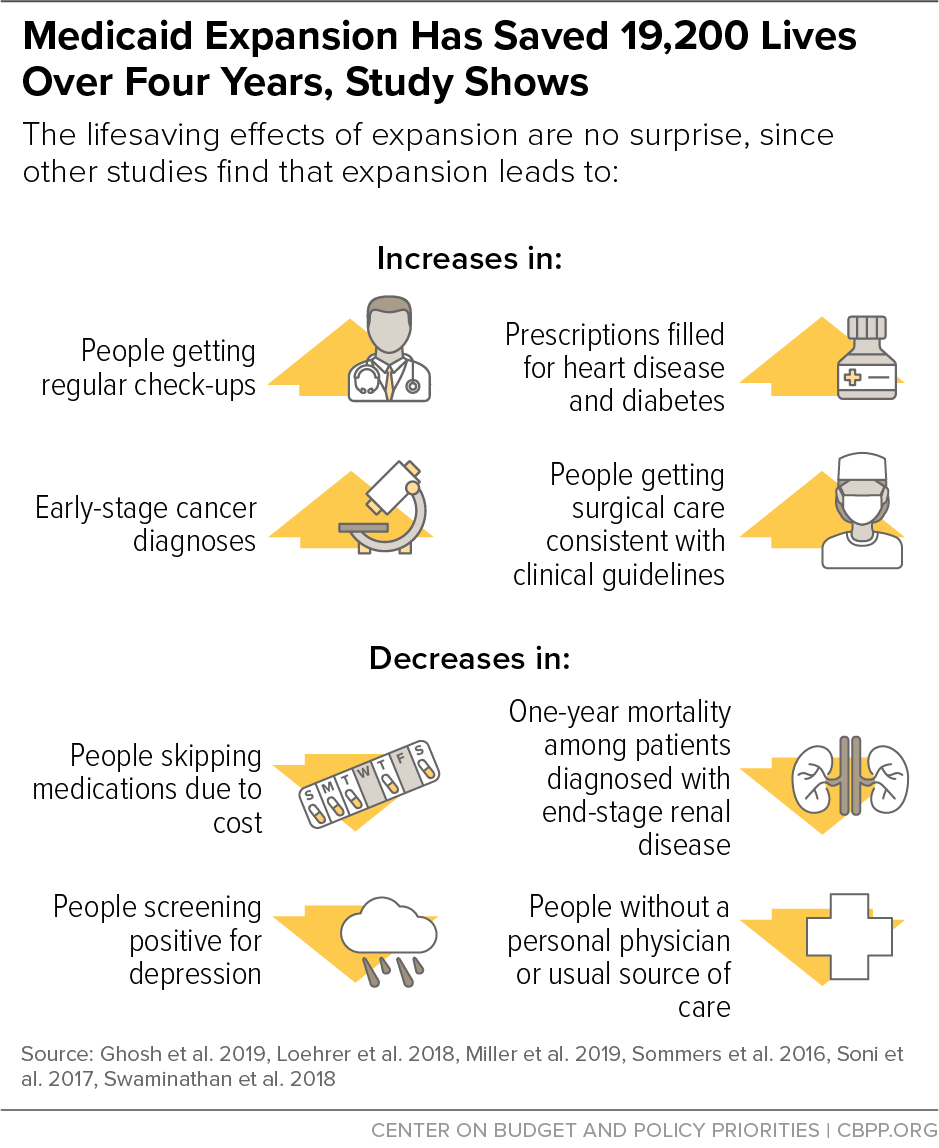

A large body of research shows Medicaid expansion beneficiaries are using coverage to obtain cancer screenings, prescription drugs, and treatment for chronic health conditions that they would not otherwise receive.[2] And these improvements in access to care have led to better health outcomes, such as improvements in self-reported health, decreases in the share of low-income adults screening positive for depression, and notably, fewer premature deaths. (See Figure 3.) Medicaid expansion saved the lives of at least 19,200 adults aged 55 to 64 over the four-year period from 2014 to 2017, a study by University of Michigan, National Institutes of Health, Census Bureau, and University of California Los Angeles researchers finds.[3] Conversely, 15,600 older adults died prematurely because of state decisions not to expand Medicaid. The lifesaving impacts of Medicaid expansion are large: an estimated 39 to 64 percent reduction in annual mortality rates for older adults gaining coverage.

Medicaid expansion is also a powerful anti-poverty tool: it reduces the medical debt of low-income Americans, improves access to credit, and significantly reduces housing evictions for renters.[4]

Among those covered through expansion are many people at elevated risk of contracting, being hospitalized for, or dying from COVID-19.

Expansion is a crucial source of health coverage for people working in essential or front-line industries: people whose jobs likely require them to show up for work regardless of stay-at-home orders or other restrictions, such as hospital workers, home health aides, food manufacturers, grocery store workers, farm workers, pharmaceutical manufacturers and pharmacy workers, bus drivers and truck drivers, and warehouse workers.[5] Among low-income workers in these jobs, many are not offered job-based coverage or, if they are, cannot afford the premiums.

Some 30 percent of low-income workers with such jobs (those with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line) were uninsured in non-expansion states in 2018, compared to 17 percent in expansion states, a sharp drop in expansion compared to non-expansion states since 2013, the last year before expansion was implemented. (See Figure 1.) Over the same period, Medicaid coverage rates for these workers rose sharply in expansion states compared to non-expansion states.

If the remaining states expanded Medicaid, we estimate that over 650,000 essential or front-line workers who are currently uninsured would become eligible for Medicaid coverage. (See Figure 4 and Appendix 1, Table 3.)

Medicaid expansion also provides health insurance coverage for people with underlying health conditions or demographic characteristics that make them more likely to get seriously ill if they contract COVID-19. For example, over 30 percent of non-elderly adults with incomes below $25,000 a year have an underlying health condition like heart disease, asthma, or diabetes that makes them more likely to get seriously ill, compared to 21 percent of all such adults.[6] Studies in Michigan and Ohio suggest that the majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees have a chronic condition that could put them at elevated risk from the virus, such as hypertension, asthma, or a heart condition.[7]

If the remaining states implemented expansion, we estimate that 940,000 uninsured people aged 50 to 64 would become eligible for Medicaid coverage, as would more than 500,000 people with disabilities (see Appendix 1, tables 1 and 2).

Expansion States Likely to Maintain Higher Coverage Levels During Recession

This recession will be the first in which the ACA’s major coverage provisions are in place. Medicaid expansion states are better positioned to maintain the high health coverage levels they achieved since the ACA took effect, while non-expansion states will likely experience larger uninsured rate increases.

Severe and sustained unemployment is expected through 2021 as a result of the public health and economic crises caused by COVID-19. The unemployment rate will peak at over 14 percent later this year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects, and will still stand at 7.6 percent at the end of 2021.[8] Already, as many as 27 million people may have lost job-based health coverage due to the recession, Kaiser Family Foundation researchers estimate.[9]

In Medicaid expansion states, many of those losing jobs and employer-based coverage will qualify for Medicaid. In non-expansion states, however, many low-income people will fall into the “coverage gap” — ineligible for Medicaid but with incomes too low to qualify for subsidized marketplace coverage. The median income limit for parents to qualify for Medicaid in non-expansion states is about 40 percent of the poverty line, or an annual income of less than $9,000 for a family of three. Of the 15 remaining non-expansion states, only one (Wisconsin) provides any Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children.[10] Even those near-poor adults who qualify for marketplace coverage are more likely to remain uninsured than if their states expanded Medicaid, since marketplace premiums, even with financial assistance, are high relative to their monthly incomes.[11]

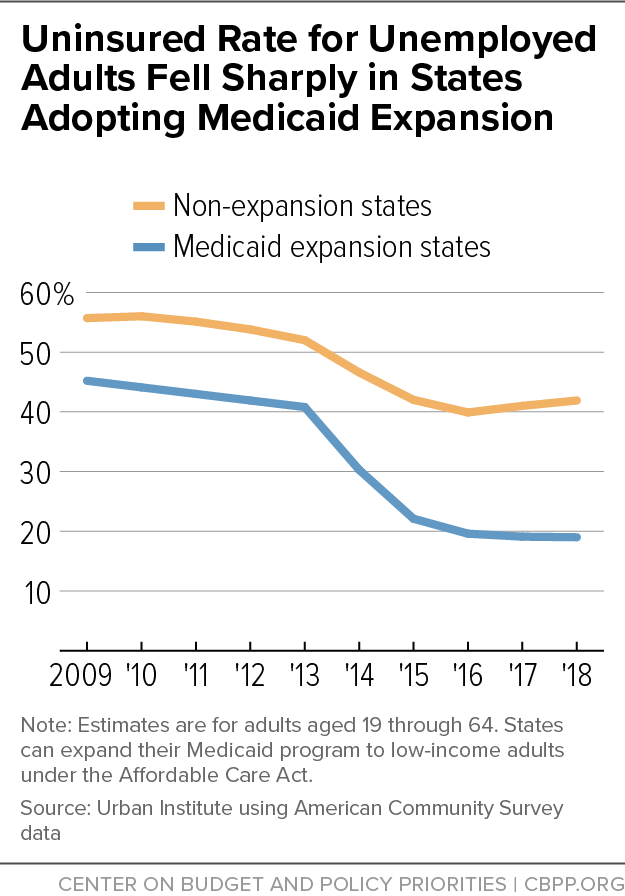

An Urban Institute analysis found that the uninsured rate among unemployed adults dropped sharply in expansion states compared to non-expansion states after implementation of the ACA’s major coverage expansions in 2014.[12] (See Figure 5.) In 2018, the uninsured rate among unemployed adults in expansion states was 19 percent, versus 42 percent in non-expansion states. Consistent with that analysis, another Urban Institute analysis projects that 23 percent of people losing job-based coverage in expansion states will become uninsured, compared to 40 percent in non-expansion states.[13]

In pre-ACA recessions the number of adults without any health coverage rose faster than the number of adults in Medicaid.[14] In non-expansion states the current recession will likely look much like previous ones, but in expansion states it will look very different, given Medicaid’s availability to far more adults.[15]

And expansion’s benefits extend beyond the adults it directly covers: it will be important for preserving children’s health coverage as well. A large and growing body of evidence shows that children are more likely to have health insurance coverage if their parents are eligible for coverage. For example, recent analysis of data from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment examined how offering Medicaid coverage to adults influenced coverage for children. Under Oregon’s pre-ACA policy, a subset of potentially eligible adults were selected at random (by lottery) to receive Medicaid coverage. Even though children were eligible for Medicaid regardless, children in households with lottery winners were significantly more likely to be enrolled.[16]

This suggests that when families lose employer-based coverage during the recession, children are more likely to stay covered in expansion states, where the whole family will be eligible for Medicaid, than in non-expansion states where the parents are ineligible.

Prior to the economic crisis, expansion covered several million parents, and another 1.1 million uninsured parents would gain Medicaid eligibility if all states expanded.[17] (See Appendix 1, Table 4.) Of note, the Urban Institute estimates that more than a quarter of those losing employer-based coverage due to the recession will be children whose parents lose their jobs.[18]

Racism, economic and health system inequities, limitations on immigrants’ eligibility for Medicaid and other public health coverage, and numerous other factors have resulted in longstanding, harmful racial disparities in coverage and access to care. Those disparities, while still significant, have narrowed since the ACA’s major coverage provisions took effect in 2014.

The gap in uninsured rates between white and Black adults shrunk by 51 percent in expansion states (versus 33 percent in non-expansion states), while the gap between white and Hispanic adults shrunk by 45 percent in expansion states (27 percent in non-expansion states). The ACA, and particularly Medicaid expansion, also helped narrow racial disparities in those not seeking care due to cost.[19] (See Figure 6.)

Medicaid expansion has also helped lower uninsured rates among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Their non-elderly adult uninsured rate fell from 31 percent in 2013 to 20 percent in 2017 in expansion states, while declining only slightly in non-expansion states.[20]

These improvements in coverage and access to care will be crucial as the COVID-19 crisis continues, as available data show that infection rates and deaths in most states are higher among Black and Hispanic people and American Indians and Alaska Natives.[21] For example, Black people make up a disproportionate share of known COVID-19 cases in 30 out of 48 states (including D.C.) reporting such data; Hispanic people make up a disproportionate share in 37 of 45 states reporting the relevant data; and American Indians and Alaska Natives make up a disproportionate share in 10 of 33 states.[22] Overall, the share of Black people in the United States who have died from COVID-19 is more than twice the share of most other groups, and death rates for Indigenous people are also particularly high.[23]

Expansion does not eliminate these disparities, which are tied to longstanding racial, economic, and health system inequities, but it does allow people to access treatment for COVID-19, as well as for underlying health conditions that may worsen its effects.

Expansion can help keep the recession from worsening health disparities. There is clear evidence that the COVID-19 recession is already hitting people with low incomes and people of color especially hard: more than half of adults in lower-income households, and 44 percent of Black and 61 percent of Hispanic adults, say they or someone in their household has lost a job or taken a pay cut due to COVID-19, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.[24]

During the Great Recession, Black people saw an especially sharp rise in uninsured rates, and both Black and Hispanic people saw a disproportionate increase in the share of people unable to access needed care due to cost.[25] As discussed above, in expansion states, this recession will differ from the last one in that most newly uninsured adults and others seeing large drops in income will be eligible for Medicaid coverage, but non-expansion states will likely see uninsured rate rises more similar to past recessions.

Of the uninsured people who would gain Medicaid eligibility if the remaining states expanded, 29 percent are Hispanic and 23 percent are Black, according to Kaiser Family Foundation estimates.[26] (See Figure 7 for estimates by state.) People of color make up a disproportionate share of those who could gain coverage through expansion, compared to their share of the population across the remaining non-expansion states. They are also disproportionately likely to reside in states that have not yet expanded Medicaid.

Since Medicaid expansion coverage took effect in 2014, it has produced net savings for many state budgets, state and independent analyses have found. That’s because, for starters, states face little upfront cost for expansion coverage. The federal government paid the entire cost of expansion coverage from 2014 to 2016, and while the federal share of costs began dropping in 2017, in 2020 and in each year going forward the federal government will pay 90 percent of those costs. (By comparison, the federal government pays between 50 and 78 percent of a state’s costs for covering other Medicaid eligibility groups.)

Meanwhile, expansion produces offsetting budget savings for many states and, in some instances, increases revenues. For example, as more people gain coverage, hospitals’ uncompensated care costs — and thus, for some states, payments to hospitals to help cover those costs — fall. These savings alone could offset more than one-third of the upfront cost of expansion across the 15 states that have not yet adopted or implemented it, the Urban Institute estimates.[27] States also spend less on programs serving people with behavioral health needs since Medicaid paid for their treatment, and less on corrections as federal Medicaid dollars paid a greater share of the inpatient hospital costs of inmates eligible for and enrolled in Medicaid. And, in states that tax managed care plans serving Medicaid beneficiaries, increased enrollment generates revenue gains that further offset the cost of expansion.[28]

A recent analysis of state budget data published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that while expansion states experienced Medicaid spending growth 24 percent higher than non-expansion states from 2013 to 2018, federal dollars entirely paid for this spending increase, “with no significant changes in spending from state revenues associated with Medicaid expansion,” compared to states that did not adopt expansion — including for 2017 and 2018, after the federal matching rate fell.[29] Further, there is “no evidence that Medicaid expansion forced states to cut back on spending on other priorities, such as education, transportation, or public assistance,” the authors found.

While this analysis predates the COVID-19 public health and economic crises, the same budgetary dynamics should operate during the recession. With millions of people losing their jobs or experiencing sharp income reductions, expansion enrollment and states’ upfront costs will indeed rise. But the offsetting savings will grow, too. That’s because, without Medicaid expansion, higher uninsurance due to the recession will increase demand (and therefore state spending) for state-funded programs serving the uninsured, like uncompensated care pools and behavioral health programs. In expansion states, Medicaid will instead serve much of this demand, with the federal government paying 90 percent of the cost.

Some states have dedicated funding sources for their Medicaid expansions that are tied to enrollment and utilization — such as increased assessments on health care providers and the managed care plans that serve Medicaid enrollees — which will generate more revenue as enrollment increases, making it likely they’ll continue to cover the entire cost of expansion.[30]

In addition, the economic stimulus that the infusion of federal dollars Medicaid expansion provides is especially valuable during a recession. A 2014 study by the Council of Economic Advisers found that Medicaid expansion would likely create or save over 350,000 jobs among states that adopted it while the economy was still recovering from the Great Recession from 2014 to 2016.[31] Newly adopting expansion could provide similar benefits to the remaining non-expansion states during the current economic downturn.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| State |

Total |

Female |

Male |

19 to 29 |

30 to 39 |

40 to 49 |

50 to 64 |

|---|

| Non-expansion states |

4,006,000 |

2,044,000 |

1,961,000 |

1,220,000 |

1,018,000 |

833,000 |

935,000 |

| Alabama |

193,000 |

93,000 |

101,000 |

61,000 |

49,000 |

39,000 |

43,000 |

| Florida |

693,000 |

349,000 |

344,000 |

193,000 |

166,000 |

149,000 |

184,000 |

| Georgia |

411,000 |

213,000 |

198,000 |

125,000 |

103,000 |

85,000 |

98,000 |

| Kansas |

77,000 |

39,000 |

38,000 |

28,000 |

19,000 |

14,000 |

16,000 |

| Mississippi |

144,000 |

73,000 |

71,000 |

51,000 |

33,000 |

26,000 |

33,000 |

| Missouri |

164,000 |

80,000 |

84,000 |

53,000 |

43,000 |

29,000 |

40,000 |

| Nebraska |

51,000 |

26,000 |

26,000 |

17,000 |

14,000 |

11,000 |

9,000 |

| North Carolina |

344,000 |

173,000 |

171,000 |

96,000 |

93,000 |

72,000 |

83,000 |

| Oklahoma |

151,000 |

75,000 |

76,000 |

44,000 |

38,000 |

30,000 |

39,000 |

| South Carolina |

154,000 |

72,000 |

82,000 |

49,000 |

29,000 |

32,000 |

44,000 |

| South Dakota |

27,000 |

12,000 |

15,000 |

10,000 |

7,000 |

6,000 |

4,000 |

| Tennessee |

191,000 |

90,000 |

101,000 |

53,000 |

41,000 |

41,000 |

55,000 |

| Texas |

1,368,000 |

730,000 |

637,000 |

426,000 |

371,000 |

294,000 |

277,000 |

| Wisconsin |

21,000 |

10,000 |

11,000 |

6,000 |

6,000 |

* |

5,000 |

| Wyoming |

14,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

6,000 |

* |

* |

* |

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 |

|---|

| State |

People with a disability |

|---|

| Non-expansion states |

|

508,000 |

|

| Alabama |

|

32,000 |

|

| Florida |

|

82,000 |

|

| Georgia |

|

49,000 |

|

| Kansas |

|

15,000 |

|

| Mississippi |

|

27,000 |

|

| Missouri |

|

28,000 |

|

| Nebraska |

|

8,000 |

|

| North Carolina |

|

44,000 |

|

| Oklahoma |

|

29,000 |

|

| South Carolina |

|

26,000 |

|

| South Dakota |

|

* |

|

| Tennessee |

|

34,000 |

|

| Texas |

|

128,000 |

|

| Wisconsin |

|

* |

|

| Wyoming |

|

* |

|

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 |

|---|

| State |

People working in an essential or front-line industry |

|---|

| Non-expansion states |

|

650,000 |

|

| Alabama |

|

25,000 |

|

| Florida |

|

113,000 |

|

| Georgia |

|

62,000 |

|

| Kansas |

|

14,000 |

|

| Mississippi |

|

22,000 |

|

| Missouri |

|

34,000 |

|

| Nebraska |

|

8,000 |

|

| North Carolina |

|

57,000 |

|

| Oklahoma |

|

22,000 |

|

| South Carolina |

|

23,000 |

|

| South Dakota |

|

5,000 |

|

| Tennessee |

|

26,000 |

|

| Texas |

|

226,000 |

|

| Wisconsin |

|

* |

|

| Wyoming |

|

* |

|

| APPENDIX TABLE 4 |

|---|

| State |

Parents |

|---|

| Non-expansion states |

|

1,118,000 |

|

| Alabama |

|

45,000 |

|

| Florida |

|

164,000 |

|

| Georgia |

|

123,000 |

|

| Kansas |

|

26,000 |

|

| Mississippi |

|

32,000 |

|

| Missouri |

|

45,000 |

|

| Nebraska |

|

15,000 |

|

| North Carolina |

|

102,000 |

|

| Oklahoma |

|

39,000 |

|

| South Carolina |

|

25,000 |

|

| South Dakota |

|

7,000 |

|

| Tennessee |

|

20,000 |

|

| Texas |

|

535,000 |

|

| Wisconsin |

|

7,000 |

|

| Wyoming |

|

* |

|

We use 2018 American Community Survey data (ACS) from the Census Bureau (the most recent available) to estimate how many adults currently without health insurance coverage would gain Medicaid eligibility in each state if the remaining 15 states implemented expansion and to estimate the share of these Medicaid expansion adults in various demographic categories.

We first identify Medicaid expansion-eligible adults in the survey data. Potential Medicaid expansion adults are defined as those who are uninsured, who are aged 19 to 64, who do not earn Supplemental Security Income, who have not given birth to a child within the last 12 months, who are not Medicare enrollees, who have income below 138 percent of the federal poverty line, and who, if they are parents, have incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid in their states today.[32] While this definition is our best approximation of the group of non-elderly adults likely eligible for Medicaid were their state to expand coverage, it does not fully capture Medicaid eligibility requirements. In particular, we are not able to identify adults ineligible for Medicaid due to their immigration status.

We use the Census Bureau survey data to estimate the distribution of this group by the following categories: gender, age group, disability status, parental status, and whether they work in an essential or front-line industry. We use the Census Bureau definition for people with a disability: those who either are deaf or have serious difficulty hearing, are blind or have serious difficulty seeing, have serious cognitive impairment, have serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs, have difficulty dressing or bathing, or have difficulty doing basic activities. We define parents as adults Census categorizes as reference persons of a household, spouses of reference persons, subfamily heads, and spouses of subfamily heads and who are living in the home with either a biological child, adopted child, stepchild, or grandchild under age 19.

We define adults in an essential or front-line industry as those working in any of the following industry categories: essential food production, essential manufacturing (including medicine), essential public services (including civic and public safety), essential transportation, essential utilities, essential warehousing, front-line health care services, front-line retail, and front-line services (including transportation). This definition is imperfect — it undoubtedly excludes some workers who have been required to show up for work while stay-home orders are in effect, while including some who have been furloughed or able to work remotely. But we believe it provides a reasonable window into current and potential health coverage for essential or front-line workers.

Estimates in the tables above exclude any demographic category for any state with an unweighted sample of less than 40 individuals in the survey data.

Our estimates differ from other recent estimates of the impact of Medicaid expansion for various reasons. The Urban Institute estimates that about 4 million uninsured people would gain health insurance coverage if all remaining states expanded.[33] Compared to our estimate of uninsured people gaining Medicaid eligibility, Urban’s estimate takes into account that not all newly eligible uninsured people would enroll, but also that expanding Medicaid would lead some already eligible people to enroll in Medicaid coverage (for example, children of newly eligible parents, as discussed above).

The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that about 4.4 million uninsured people would have gained coverage had all states expanded Medicaid prior to the current public health and economic crisis.[34] Modest differences from our estimates reflect different approaches to identifying likely Medicaid-eligible individuals using the information available in the Census data.