How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity

2017 Tax Law Took Step Backward

End Notes

[1] The authors thank the reviewers of this paper for their thoughtful and invaluable feedback.

[2] Arloc Sherman and Tazra Mitchell, “Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long Term, Many Studies Find,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-succeed-over.

[3] For more information on the racial and ethnic disparities in debt collection, see https://library.nclc.org/fdc/01030105.

[4] This paper uses the term “inclusive” to refer to policies to promote opportunity that are not just race neutral but likely to actually benefit households of color, even taking into account current disparities and systemic barriers to economic success for these households. Fully inclusive policies account for, and are well-designed to overcome, both financial and non-financial barriers (such as language and cultural considerations) to equitable outcomes.

[5] For more discussion of the “facially neutral” but racially differential impacts of tax policy and administration, see: Misha Hill et al., “The Illusion of Race-Neutral Tax Policy,” ITEP, February 14, 2019, https://itep.org/the-illusion-of-race-neutral-tax-policy/; Darrick Hamilton and Michael Linden, “Hidden Rules of Race Are Embedded in the New Tax Law,” Roosevelt Institute, May 2018, http://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Hidden-Rules-of-Race-and-Trump-Tax-Law.pdf; Dorothy Brown, “Racial Equality in the Twenty-First Century: What’s Tax Policy Got to Do with It,” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review, Vol. 21, No. 759, 1999, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2468239; and Kasey Henricks and Louise Seamster, “Mechanisms of the Racial Tax State,” Critical Sociology, October 11, 2016, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0896920516670463?journalCode=crsb.

[6] For citations and a discussion of how various state policies — both historically and currently — reinforce racial disparities, see Michael Leachman, Michael Mitchell, Nicholas Johnson, and Erica Williams, “Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy; and Angela Hanks, Danyelle Solomon, and Christian E. Weller, “Systematic Inequality: How America’s Structural Racism Helped Create the Black-White Wealth Gap,” Center for American Progress, February 21, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2018/02/21/447051/systematic-inequality/; and Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Liveright, 2017.

[7] Rothstein.

[8] David Cooper, “Workers of Color Are Far More Likely to Be Paid Poverty-Level Wages Than White Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, June 21, 2018, https://www.epi.org/blog/workers-of-color-are-far-more-likely-to-be-paid-poverty-level-wages-than-white-workers/.

[9] S. Michael Gaddis, “Discrimination in the Credential Society: An Audit Study of Race and College Selectivity in the Labor Market,” Social Forces, Vol. 93, Issue 4, June 1, 2015, pp. 1451–1479, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou111.

[10] “Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System,” The Sentencing Project, April 19, 2018, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/.

[11] Karin D. Martin, Sandra Susan Smith, and Wendy Still, “Shackled to Debt: Criminal Justice Financial Obligations and the Barriers to Re-Entry They Create,” New Thinking in Community Corrections Bulletin, January 2017, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249976.pdf.

[12] Other examples include: white narratives and stereotypes about who is a “taxpayer” that have erected racial barriers to economic opportunity, such as equal education (for one discussion, see Camille Walsh, Racial Taxation: Schools, Segregation, and Taxpayer Citizenship, 1869–1973, University of North Carolina Press, 2008, Chapter 2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469638966_walsh); states’ use of poll taxes and grandfather clauses to prevent people of color from voting in federal and state elections (for a brief summary, see Leachman et al.,); the IRS’ approval before 1970 of charitable tax-exempt status for private schools that racially discriminated against applicants and students (in Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574, the Supreme Court ultimately upheld as constitutional the IRS’ denial of tax-exempt status to a university that denied admission to students who engaged in interracial dating or marriage); and businesses’ ability to deduct from their income taxes punitive damages for racially discriminating against employees (see Brown; also see Vanessa Williamson, “Taxation for Representation: How Taxes can Build a Stronger Democracy,” forthcoming).

[13] Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution reads in part: “Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states which may be included within this union, according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.”

[14] For brief surveys of relevant legal decisions and commentary, see Alan O. Dixler, “Direct Taxes Under the Constitution: A Review of the Precedents,” Tax Analysts, November 20, 2006, http://www.taxhistory.org/thp/readings.nsf/ArtWeb/2B34C7FBDA41D9DA8525730800067017; and Ari D. Glogower, “A Constitutional Wealth Tax,” Michigan Law Review, forthcoming, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3322046.

[15] A number of framers were explicitly concerned with whether the Constitution would permit federal taxes that would “amount to manumission” or prohibit or undermine slavery, but it is not clear whether the framers understood how the apportionment rule would restrict the design of various taxes. For an at-length discussion, see Robin L. Einhorn, American Taxation, American Slavery, University of Chicago Press, 2008. For a briefer summary, see Robin L. Einhorn, “Tax Aversion and American Slavery,” essay for University of Chicago Press, 2006, https://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/194876.html.

[16] Joseph J. Thorndike, “The Origins of the American Income Tax: The Revenue Act of 1894 and Its Aftermath,” Tax Analysts, May 23, 2005, http://www.taxhistory.org/thp/readings.nsf/0/1fe74d7f2f033e738525701300527150. Part of this barrier is practical, as it is extremely difficult both practically and politically to set tax rates on different types of income or wealth that would meet the apportionment requirement. See Einhorn, Chapter 5.

[17] The tax was levied at 2 percent of corporate and individual income (above an exemption level for individual income), and it explicitly included in taxable income any increase in net wealth, such as inheritances and gifts. See Thorndike; and Richard J. Joseph, The Origins of the American Income Tax: The Revenue Act of 1894 and Its Aftermath, Syracuse University Press, 2004, pp. 119, https://press.syr.edu/supressbooks/1095/origins-of-the-american-income-tax/.

[18] Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company, 158 U.S. 601 at 695 (1895), dissenting opinion, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/158/601/

[19] Dixler.

[20] Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Company. The dissent referenced in the text was delivered by Justice Henry Brown, but far from being a reliable voice on the court in favor of advancing racial equity, Justice Brown is primarily known for delivering the infamous majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, which reified the legal structure for Jim Crow racial segregation for decades. For more on Plessy v. Ferguson, see Steve Luxenberg, Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America's Journey from Slavery to Segregation, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2019.

[21] Glogower.

[22] Bruce Ackerman, “Taxation and the Constitution,” Yale Law School Faculty Scholarship Series, 1999, https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1126&context=fss_papers.

[23] For example, Rubin and Stankiewicz note that some racial equity advocates campaigned for the New Markets Tax Credit.

[24] For a summary of the impacts of the New Markets Tax Credit and other place-based tax incentives such as Empowerment Zones, finding limited evidence of positive impacts or cost effectiveness, see “Tax Expenditures: Compendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions,” Congressional Research Service, December 2016, pp. 587-591 and pp. 597-601, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-114SPRT24030/pdf/CPRT-114SPRT24030.pdf.

[25] See Henricks and Seamster, p. 5.

[26] See Samantha Jacoby, “Potential Flaws of Opportunity Zones Loom, as Do Risks of Large-Scale Tax Avoidance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 11, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/potential-flaws-of-opportunity-zones-loom-as-do-risks-of-large-scale-tax; and Congressional Black Caucus Foundation letter on opportunity zones, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=IRS-2018-0029-0130.

[27] Ibid.

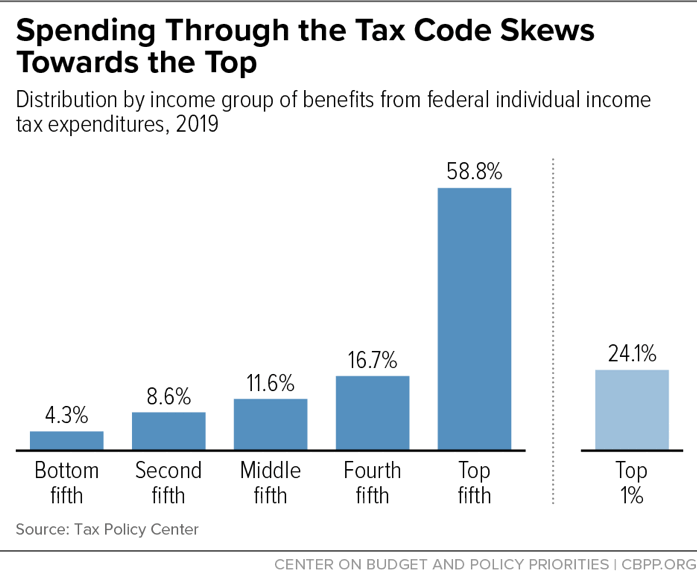

[28] This paper illustrates three main types of racial income and wealth inequality and the tax code’s impact on each. First, some examples illustrate “vertical” racial disparities, or those between high-income people (who are disproportionately white) and low-income people (who are disproportionately people of color). Reducing overall income inequality reduces the size of after-tax income and wealth gaps between high- and low-income filers, and so reduces racial income gaps between disproportionately white high-income filers and other filers. Just as there is no single measure of the extent to which a tax code reduces this type of inequality (see: Chye-Ching Huang and Nathaniel Frentz, “What Do OECD Data Really Show About U.S. Taxes and Reducing Inequality?” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 13, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/what-do-oecd-data-really-show-about-us-taxes-and-reducing-inequality), there is no single measure for how a progressive tax code might reduce racial income and wealth gaps between those at the top and those lower down in the income or wealth distribution.

Secondly, the paper illustrates “horizontal” racial disparities: comparing white households and households of color that have the same income or wealth, the tax code (or provisions of it) may affect white households differently than households of color, on average. See the box, “‘Colorblind’ Tax Data Poses Challenges for Racial Equity in Tax Policy,” and the discussion of the mortgage interest deduction and tax breaks, for further discussion.

Third, achieving greater racial equity would mean dismantling barriers that hold back households of color from realizing economic success and thereby being represented in the higher rungs of the income and wealth distribution in proportion to their share of the population. There is less research on how public policy overall and tax policy in particular might promote economic mobility, especially of the sort that narrows racial disparities. (Economist Raj Chetty, for example, has recently produced some important but early work seeking to understand determinants of mobility. See: Raj Chetty et al., “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,” NBER Working Paper No. 24441, March 2018, https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/race_paper.pdf) This paper touches on some tax policies that might improve racial equity on this dimension. It explains, for example, that research shows that income boosts from tax credits such as the EITC and CTC increase the likelihood that children in low-income families earn more as adults. It also discusses the taxation of large inheritances, explaining that inheritances are an important determinant of economic mobility across generations.

[29] See Hanks, Solomon, and Weller; and Leachman et al.

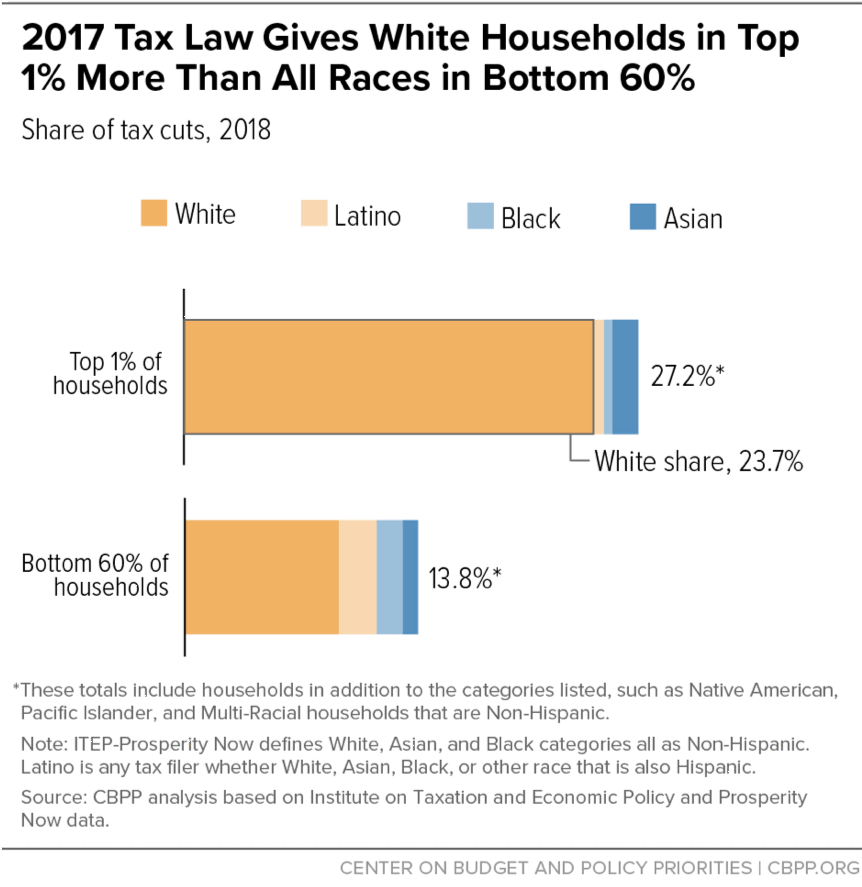

[30] “Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Prosperity Now, October 11, 2018, https://itep.org/race-wealth-and-taxes-how-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-supercharges-the-racial-wealth-divide/. See endnote 33 below for discussion of disaggregation of various racial/ethnic categorizations.

[31] Ibid.

[32] It is unclear how the federal tax code overall affects racial equity at different parts of the income distribution. Such estimates are more difficult to make than assessing the tax code’s mechanical effects on overall inequality and racial inequality across the income distribution. See box, “‘Colorblind’ Tax Data Poses Challenges for Racial Equity in Tax Policy,” for a more complete discussion.

[33] Available estimates from ITEP (discussed in more detail later in the paper) show that “Asian Americans,” defined as people with ancestral origins in East Asia, South Asia, or Southeast Asia, are disproportionately represented among higher-income groups relative to their share of the population. However, this aggregation conceals the wide economic disparities between different Asian-American ethnic groups. The same issue applies to Pacific Islander Americans, which in the ITEP estimates are grouped in the “Other” category. See, for example, Sono Shah and Karthick Ramakrishnan, “Why Disaggregate? AAPI Unemployment and Poverty,” Data Bits, April 17, 2017, http://aapidata.com/blog/countmein-unemployment-poverty/, which shows that some Asian American and Pacific Islander groups are disproportionately represented at the bottom of the income distribution, while others are disproportionately represented at the top. However, disaggregation is not provided in the ITEP estimates due to small sample size. Native Americans also are not listed separately in the ITEP estimates due to small sample size, but other data sources show that Native Americans are disproportionately represented at the bottom of the income distribution. See Valerie Wilson, “Digging into the 2017 ACS: Improved income growth for Native Americans, but lots of variation in the pace of recovery for different Asian ethnic groups,” Economic Policy Institute, September 14, 2018, https://www.epi.org/blog/digging-into-2017-acs-income-native-americans-asians./.

[34] Tax Policy Center table T18-0085, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/baseline-average-effective-tax-rates-august-2018/t18-0085-average-effective-federal.

[35] For more information, see the following CBPP backgrounders: “Policy Basics: Marginal and Average Tax Rates,” updated June 21, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-marginal-and-average-tax-rates; “Policy Basics: Federal Payroll Taxes,” updated June 24, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-federal-payroll-taxes; and “Policy Basics: Where do Federal Tax Revenues Come From?” updated June 20, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-where-do-federal-tax-revenues-come-from.

[36] See Michael Leachman, “State, Local Tax Systems Worsening Inequality,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 17, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/state-local-tax-systems-worsening-inequality; and Leachman et al.

[37] Leachman et al.

[38] Isaac William Martin and Kevin Beck, “Property Tax Limitation and Racial Inequality in Effective Rates,” Critical Sociology, Vol.43(2), 2017, pp. 221-236.

[39] Steve Wamhoff and Matthew Gardner, “Who Pays Taxes in America in 2019,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 11, 2019, https://itep.org/who-pays-taxes-in-america-in-2019/.

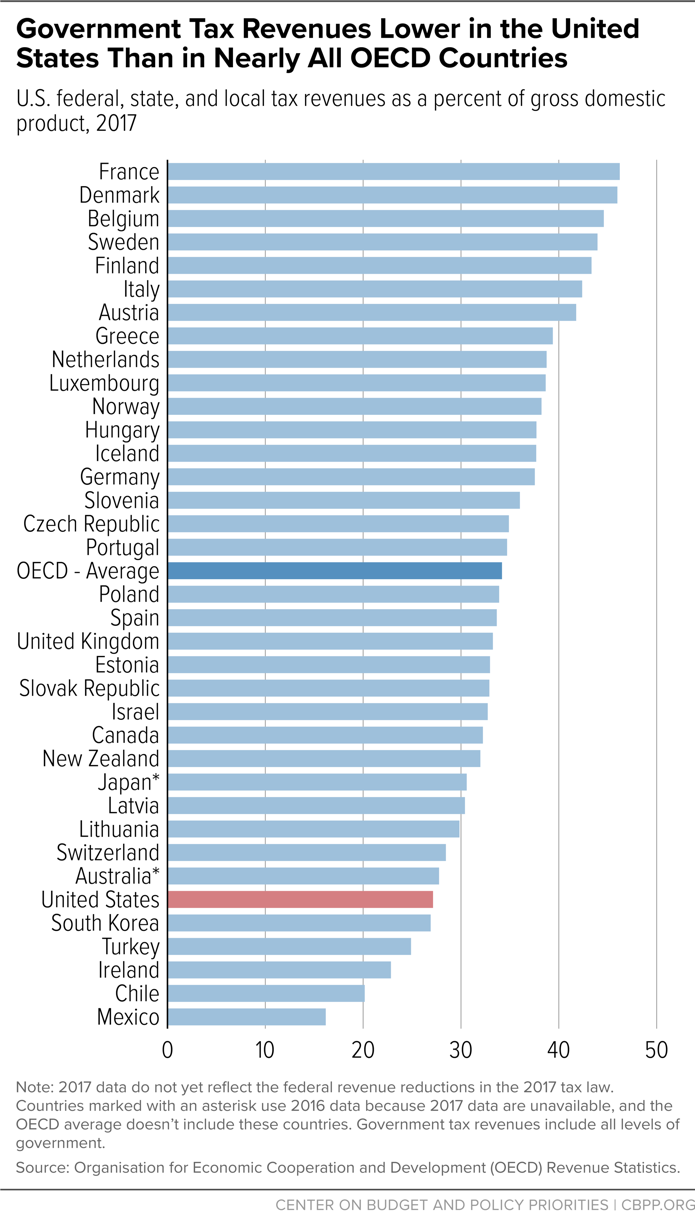

[40] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Revenue Statistics 2018, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/rev_stats-2018-en.

[41] Based on reductions in the Gini measure of inequality among 33 countries for which OECD data for 2016 or the latest available year are available (see OECD Income Distribution Database, 2019). The United States ranks above only New Zealand, Israel, Switzerland, Korea, and Chile on this measure. (Data for Mexico, Hungary, and Turkey are unavailable.) While these are the most recent and complete estimates available, they have significant limitations, though it is not clear how those limitations would affect the overall conclusion. See Chye-Ching Huang and Nathaniel Frentz, “What Do OECD Data Really Show About U.S. Taxes and Reducing Inequality?” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 13, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/what-do-oecd-data-really-show-about-us-taxes-and-reducing-inequality.

[42] For a more detailed review and discussion of this literature, see Rourke L. O’Brien, “Redistribution and the New Fiscal Sociology: Race and the Progressivity of State and Local Taxes,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 122, No. 4, January 2017, pre-publication draft available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6101670/.

[43] Ibid.

[44] For examples see Einhorn; Ife Floyd, “States Should Repeal Racist Policies Denying Benefits to Children Born to TANF Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 30, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-should-repeal-racist-policies-denying-benefits-to-children-born-to-tanf-families; and O’Brien.

[45] O’Brien.

[46] Ibid., citing Martin Gilens, Why Americans Hate Welfare, University of Chicago Press, 1999; and Erzo F.P. Luttmer, “Group Loyalty and the Taste for Redistribution,” University of Chicago Press Journals, June 2001, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/321019. Also note that surveys repeatedly show that respondents generally greatly overestimate the share of people benefiting from various public economic security programs who are people of color. See, for example, http://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/tabsHPGovernmentprograms20180116.pdf.

[47] O’Brien.

[48] See, for example, Ian F. Haney- López, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class, Oxford University Press, 2014. Also see “Dog Whistle Politics: How Politicians Use Coded Racism to Push Through Policies Hurting All,” Democracy Now, January 14, 2014, https://www.democracynow.org/2014/1/14/dog_whistle_politics_how_politicians_use.

[49] Rick Perlstein, “Exclusive: Lee Atwater’s Infamous 1981 Interview on the Southern Strategy,” The Nation, November 13, 2012, https://www.thenation.com/article/exclusive-lee-atwaters-infamous-1981-interview-southern-strategy/. Furthermore, some researchers have argued that such dog whistles may also rest on the cultivation of an idea that "whiteness was automatically presumed to imply ‘taxpayer,’” regardless of actual taxation levels; see Haney-López, also see Walsh.

[50] “Chart Book: Accomplishments of Affordable Care Act,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 19, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/chart-book-accomplishments-of-affordable-care-act.

[51] Samantha Artiga, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since Implementation of the ACA, 2013-2017,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 13, 2019, https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-implementation-of-the-aca-2013-2017/.

[52] See “KFF Health Tracking Poll: The Public’s Views on the ACA,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 24, 2019, https://www.kff.org/interactive/kff-health-tracking-poll-the-publics-views-on-the-aca/#?response=Favorable--Unfavorable&aRange=twoYear; and Kevin Fiscella, “Why Do So Many White Americans Oppose the Affordable Care Act?” American Journal of Medicine, May 2016, https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(15)00930-4/fulltext.

[53] See KFF health tracking poll; and Hannah Fingerhut, “For the first time, more Americans say 2010 health care law has had a positive than negative impact on U.S.,” Pew Research Center, December 11, 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/12/11/for-the-first-time-more-americans-say-2010-health-care-law-has-had-a-positive-than-negative-impact-on-u-s/.

[54] “Policy Basics: Federal Tax Expenditures,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated April 9, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-federal-tax-expenditures.

[55] Another example is the Affordable Care Act premium tax credits, which help individuals with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line afford healthcare premiums (see Aviva Aron-Dine and Matt Broaddus, “Improving ACA Subsidies for Low- and Moderate-Income Consumers Is Key to Increasing Coverage,” March 21, 2019, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/improving-aca-subsidies-for-low-and-moderate-income-consumers-is-key-to-increasing). And while there is much room to improve or redirect higher education tax subsidies to make them more effective and inclusive, the refundable portion of the American Opportunity Tax Credit is the tax provision most available to low- and moderate-income students with higher education expenses (for example, see reports cited in Robert Greenstein, “Obama’s Education Tax Proposals Would Help Middle-Class Families, Not Hurt Them as Opponents Inaccurately Claim,” January 22, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/obamas-education-tax-proposals-would-help-middle-class-families-not-hurt-them-as-opponents).

[56] Cooper.

[57] Based on Census Bureau data, we estimate that the CTC serves 22 percent of white households, 22 percent of Black households, 23 percent of Latino households, 27 percent of Asian households, and 24 percent of Native American households. Of households (that is, tax filing units) receiving the CTC, 61 percent are white, 13 percent are Black, 17 percent are Latino, 7 percent are Asian, and 1 percent are Native American. The EITC serves 9 percent of white households, 18 percent of Black Households, 17 percent of Latino households, 11 percent of Asian households, and 20 percent of Native American households. Of the households receiving the EITC, 48 percent are white, 20 percent are Black, 23 percent are Latino, 5 percent are Asian, and 1 percent are Native American, we estimate.

[58] Sherman and Mitchell.

[59] This section selects some illustrative examples. Also see the foundational work of Beverly I. Moran and William C. Whitford (“A Black Critique of the Internal Revenue Code,” Wisconsin Law Review, 1996-1997, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1142912), who examined various categories of tax expenditures by race and argued that they “systematically disfavored the financial interests of blacks,” both due to their tilt toward the wealthy and even when holding income and wealth constant. Subsequently, other researchers have undertaken similar analyses of various elements of the tax code, focusing on other races and ethnicities. Also see Leo P. Martinez and Jennifer M. Martinez, “The Internal Revenue Code and Latino Realities: A Critical Perspective,” 22 U. Fla. J.L. & Pub. Pol'y 377 (2011), https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/1441; and Mylinh Uy, “Tax and Race: The Impact on Asian Americans,” Asian American Law Journal, January 2004, https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?&httpsredir=1&article=1096&context=aalj. (Uy emphasizes the importance of data disaggregation when analyzing the tax code’s impact on Asian Americans.) Also see Francine J. Lipman, “Taxing Undocumented Immigrants: Separate, Unequal, and Without Representation,” Harvard Latino Law Review, Spring 2006, for a summary of how various tax code provisions affect immigrant families differentially. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=881584.

For summaries of similar research, also see Table 1 in Jeremy Bearer-Friend, “Should the IRS Know Your Race? The Challenge of Colorblind Tax Data,” 73 Tax Law Review, forthcoming; abstract available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3231315; and Dedrick Asante-Muhammad et al., “The Ever-Growing Tax Gap: Without Change, African-American and Latino Families Won’t Match White Wealth for Centuries,” Prosperity Now, August 9, 2016, https://prosperitynow.org/resources/ever-growing-gap-without-change-african-american-and-latino-families-wont-match-white.

[60] Lewis Brown Jr. and Heather McCulloch, “Building an Equitable Tax Code: A Primer for Advocates,” PolicyLink, July 1, 2015, http://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/pl_brief_tax_110714_c_0.pdf.

[61] Roughly three-quarters of households claiming the mortgage interest deduction in 2018 had income of at least $100,000, and they received almost 90 percent of the total dollar value of the deduction. See “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Joint Committee on Taxation, October 4, 2018, pp. 41, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5149.

[62] See Joint Committee on Taxation documents JCX-81-18 and JCX-3-17. We compare JCT estimates of the mortgage interest deduction under 2017 law (before the 2017 tax law took effect) at 2016 income levels with the deduction under 2018 law and income levels.

[63] Will Fischer and Chye-Ching Huang, “Mortgage Interest Deduction Is Ripe for Reform,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 25, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/mortgage-interest-deduction-is-ripe-for-reform.

[64] For an overview of the literature on Black households’ barriers to homeownership, access to affordable debt, and ability to accumulate wealth through homeownership, see Dorothy A. Brown, “Homeownership in Black and White: The Role of Tax Policy in Increasing Housing Inequity,” University of Memphis Law Review, 2018, pp.213-223, I https://www.memphis.edu/law/documents/brown_final.pdf; and Hanks, Solomon, and Weller. Hispanic households also face systemic barriers to homeownership, as discussed in “State of Hispanic Homeownership Report,” Hispanic Wealth Project, March 28, 2018, http://hispanicwealthproject.org/shhr/2017-state-of-hispanic-homeownership-report.pdf.

[65] Benjamin H. Harris and Lucie Parker, “The Mortgage Interest Deduction Across Zip Codes,” Tax Policy Center, December 4, 2014, pp. 7, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/mortgage_interest_deductions_harris.pdf.

[66] See Hanks, Solomon, and Weller; Brown; and Moran and Whitford.

[67] Moran and Whitford likewise argued that a number of provisions exempting wealth, or income from wealth, from taxation — including the ability to defer paying taxes on capital gains until realization — are systematically biased against Black households.

[68] For more on the estate tax, see “Policy Basics: The Federal Estate Tax,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated November 7, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-federal-estate-tax; and Roderick Taylor, “New Estate Tax Cut Encourages More Wealthy Individuals to Skirt Capital Gains Tax,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 17, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/new-estate-tax-cut-encourages-more-wealthy-individuals-to-skirt-capital-gains-tax.

[69] See Len Burman, Amanda Eng, and Eric Toder, “Tax Cuts and Pre-Tax Income Inequality,” Tax Policy Center, February 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20140826075602/http://lawweb.usc.edu/who/faculty/conferences/income-inequality/documents/Burman-Eng-Toder-v2.pdf. This presentation shows that because a regressive tax cut (or regressive tax subsidy) adds to a filer’s pre-tax wealth in the next tax year, its effect can become still more unequal over time as the gains accumulate. This mechanical effect can occur even if the tax cut or tax break has no “supply-side” effect of causing the filer to save or invest more of any additional dollar he or she has available. Proponents of cutting taxes on capital income often claim that it will have this supply-side effect, which in turn might produce economic growth with more inclusive benefits, but little empirical evidence suggests that any such effect is substantial or outweighs the negative impacts of the increase in national debt. See Chye-Ching Huang and Chuck Marr; “Raising Today’s Low Capital Gains Tax Rates Could Promote Economic Efficiency and Fairness, While Helping Reduce Deficits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 19, 2012. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/9-19-12tax.pdf.

[70] Moran and Whitford, p. 759.

[71] Ibid.

[72] For example, see Amy Traub et al., “The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters,” Demos, June 21, 2016, https://www.demos.org/research/racial-wealth-gap-why-policy-matters.

[73] For example, some emerging research documents the long-lasting impacts on economic outcomes across generations, tracing back to slavery. See Philipp Ager, Leah Platt Boustan, and Katherine Eriksson, “The Intergenerational Effects of a Large Wealth Shock: White Southerners After the Civil War,” NBER Working Paper No. 25700, March 2019, https://www.gwern.net/docs/economics/2019-ager.pdf; and William J. Collins and Marianne H. Wanamaker, “Up From Slavery? African American Intergenerational Economic Mobility Since 1880,” NBER Working Paper No. 23395, May 2017, https://www.nber.org/papers/w23395.pdf.

[74] Joseph.

[75] Nigel Chiwaya, Ben Popken, and Jeremia Kimelman, “As calls for a wealth tax grow, here’s how wide the wealth gap is,” NBC News, , March 1, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/ultra-wealthy-americans-wealth-tax-proposals-2019-n976396.

[76] Other examples of racial disparities in tax administration and in filers’ experience of the tax code include: the potential inequality in access to the tax regulatory process through lobbying; the underrepresentation of Black and Latino people in the various tax professions (see Alice Abreu and Richard Greenstein, “Rebranding Tax/Increasing Diversity,” Denver Law Review, March 3, 2019, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3156578); and the lack of regular official estimates on the racial impact of the tax code or specific tax proposals or provisions, which “obscure[s] racial inequality and prevent[s] its remedy.” (See Jeremy Bearer-Friend, “Should the IRS Know Your Race? The Challenge of Colorblind Tax Data,” 73 Tax Law Review, forthcoming, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3231315.)

[77] Paul Kiel, “Alabama Senator to the IRS: Stop Picking on the South,” ProPublica, April 5, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/alabama-senator-doug-jones-to-irs-stop-picking-on-the-south. The IRS defines the term “audit” broadly to include not only face-to-face audits by field agents but also correspondence and phone calls between the agency and taxpayers after they file their returns.

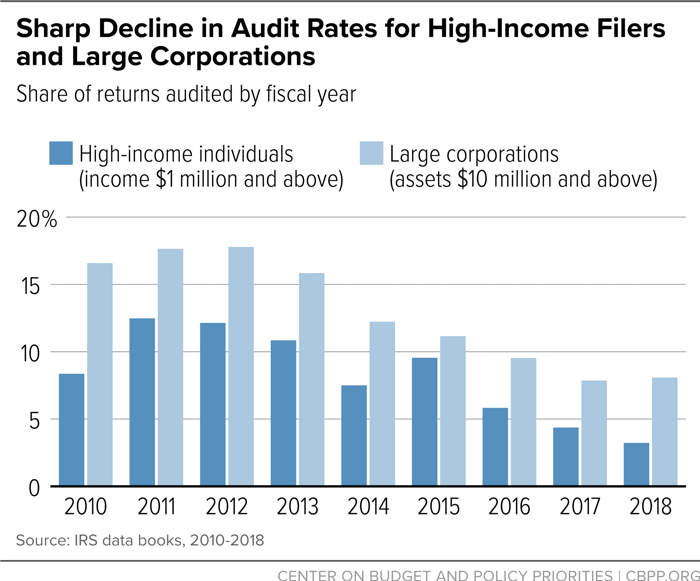

[78] Chuck Marr and Roderick Taylor, “Bipartisan Support for Budget Mechanism to Boost IRS Enforcement Is Promising First Step,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 9, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/bipartisan-support-for-budget-mechanism-to-boost-irs-enforcement-is-promising.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Paul Kiel and Jesse Eisinger, “Who’s More Likely to Be Audited: A Person Making $20,000 — or $400,000?,” ProPublica, December 12, 2018, https://www.propublica.org/article/earned-income-tax-credit-irs-audit-working-poor.

[81] IRS data books, 2010-2018.

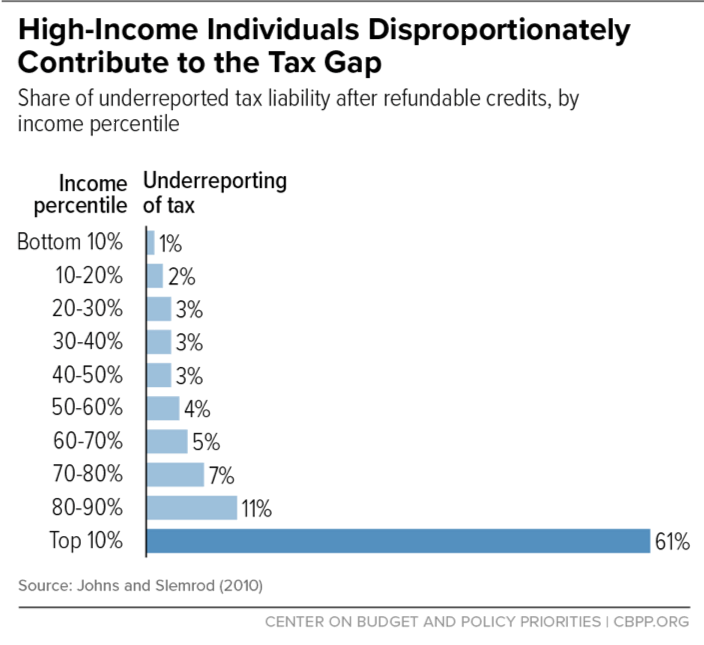

[82] Andrew Johns and Joel Slemrod, “The Distribution of Income Tax Noncompliance,” National Tax Journal, September 2010, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/5219189/The-Distribution-of-Tax-Noncompliance.pdf.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Kiel and Eisinger.

[85] Jesse Eisinger and Paul Kiel, “The IRS Tried to Take on the Ultrawealthy. It Didn’t Go Well.” ProPublica, April 5, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/ultrawealthy-taxes-irs-internal-revenue-service-global-high-wealth-audits.

[86] Karie Davis-Nozemack, “Unequal Burdens in EITC Compliance,” Law & Inequality, 2013, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1188&context=lawineq.

[87] Congressional Budget Office, “Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2019-2028,” December 2018, pp. 307, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-06/54667-budgetoptions-2.pdf.

[88] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Improving Co-operation between Tax Authorities and Anti-Corruption Authorities in Combating Tax Crime and Corruption,” OECD Publishing, October 22, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/tax/crime/improving-co-operation-between-tax-authorities-and-anti-corruption-authorities-in-combating-tax-crime-and-corruption.pdf.

[89] “Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System,” The Sentencing Project, April 19, 2018, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/.

[90] National“National Taxpayer Advocate Annual Report to Congress 2018,” February 2019, Vol. I, https://taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/Media/Default/Documents/2018-ARC/ARC18_Volume1.pdf.

[91] Ibid.

[92] “National Taxpayer Advocate Expresses Concern to Congress About Private Debt Collection,” May 13, 2014, https://taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/userfiles/file/NTA_PDC_letter.pdf.

[93] “Coalition letter sent to members of the U.S. Senate,” April 28, 2014, https://dontmesswithtaxes.typepad.com/tax-debt-collection-consumer-coalition-letter-to-Senate.pdf.

[94] “National Taxpayer Advocate Annual Report to Congress 2018,” February 2019, Vol. I, https://taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/Media/Default/Documents/2018-ARC/ARC18_Volume1.pdf.

[95] For more information on the racial and ethnic disparities in debt collection, see https://library.nclc.org/fdc/01030105. Rules governing debt collectors recently proposed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau could potentially make matters worse, by creating even more scope for debt collectors to harass consumers; see “Consumer Watchdog’s Proposed Debt Collection Rule Bites Consumers: Authorizes Harassment by Debt Collectors,” National Consumer Law Center, May 7, 2019, https://www.nclc.org/media-center/consumer-watchdogs-proposed-debt-collection-rule-bites-consumers-authorizes-harassment-by-debt-collectors.html.

[96] Fichtner, Jason J. Fichtner, William G. Gale, and Jeff Trinca, “Tax Administration: Compliance, Complexity, and Capacity,” Bipartisan Policy Center, April 8, 2019, pp. 13, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Tax-Administration-Compliance-Complexity-Capacity.pdf.

[97] See “IRS Encourages Native Americans to Check Eligibility for Earned Income Tax Credit,” Internal Revenue Service, January 30, 2018, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-encourages-native-americans-to-check-eligibility-for-earned-income-tax-credit.

[98] For more information on the outreach efforts to tribal and native communities, see https://www.eitcoutreach.org/outreach-strategies/native/.

[99] For more information on well-targeted programs, see Roxy Caines, “Celebrating 50 Years of VITA,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 13, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/celebrating-50-years-of-vita; and http://www.healthreformbeyondthebasics.org/vita-programs-and-the-affordable-care-act/.

[100] “Low Income Taxpayer Clinics,” Taxpayer Advocate Service, May 2019, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3319.pdf.

[101] Ibid.

[102] Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 14, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-tax-law-is-fundamentally-flawed-and-will-require-basic-restructuring.

[103] Meg Wiehe, Emanuel Nieves, Jeremie Greer, and David Newville, “Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Prosperity Now, October 2018, https://prosperitynow.org/sites/default/files/resources/ITEP-Prosperity_Now-Race_Wealth_and_Taxes-FULL%20REPORT-FINAL_6.pdf.

[104] Ibid.

[105] Hamilton and Linden. See also Tracy Jan, “1 in 7 white families are now millionaires. For Black families, it’s 1 in 50,” Washington Post, October 3, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/10/03/white-families-are-twice-as-likely-to-be-millionaires-as-a-generation-ago/; and Maury Gittleman and Edward N. Wolff, “Racial Differences in Patterns of Wealth Accumulation,” Journal of Human Resources, Winter 2004, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3559010.

[106] “Pass-Through Deduction Benefits Wealthiest, Loses Needed Revenue, and Encourages Tax Avoidance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 27, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/pass-through-deduction-benefits-wealthiest-loses-needed-revenue-and-encourages.

[107] Wiehe et al.

[108] “2017 Tax Law’s Child Credit: A Token or Less-Than-Full Increase for 26 Million Kids in Working Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 27, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/2017-tax-laws-child-credit-a-token-or-less-than-full-increase-for-26-million.

[109] Chuck Marr, “Instead of Boosting Working-Family Tax Credit, GOP Tax Bill Erodes It Over Time,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 21, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/instead-of-boosting-working-family-tax-credit-gop-tax-bill-erodes-it-over-time.

[110] Jacob Leibenluft, “Tax Bill Ends Child Tax Credit for About 1 Million Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 18, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/tax-bill-ends-child-tax-credit-for-about-1-million-children.

[111] Marr, Duke, and Huang.

[112] For more on workplace fissuring, see Brendan Duke, “2017 Tax Law’s Pass-Through Deduction Could Encourage ‘Workplace Fissuring,’” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 20, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/2017-tax-laws-pass-through-deduction-could-encourage-workplace-fissuring.

[113] Paul Van de Water, “2017 Tax Law Heightens Need for More Revenues,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/2017-tax-law-heightens-need-for-more-revenues.

[114] Joel Friedman and Richard Kogan, “House GOP Budget Retains Tax Cuts for the Wealthy, Proposes Deep Program Cuts for Millions of Americans,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 28, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/house-gop-budget-retains-tax-cuts-for-the-wealthy-proposes-deep-program-cuts.

[115] Theodoric Meyer, “It’s a giant present to the tax lobbying community: K street lobbyists are banking on years of paydays from the tax overhaul,” Politico, January 2, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/01/02/tax-overhaul-paydays-for-k-street-261668.

[116] Samantha Jacoby, “Commentary: New York Times Investigation Highlights Failures in Taxing Income From Wealth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 30, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/federal-tax/commentary-new-york-times-investigation-highlights-failures-in-taxing-income-from-wealth.

[117] Lily Batchelder, “The ‘silver spoon’ tax: how to strengthen wealth transfer taxation,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, October 31, 2016, https://equitablegrowth.org/silver-spoon-tax/.

[118] For example, Moran and Whitford suggested that the metaphorical construct of a “Black Congress” (that is, a “Congress that is oriented to the interests of blacks”) would tax income as it accrues on investments in publicly traded securities and nonresidential real estate, and would repeal special tax rates for capital gains. See Moran and Whitford, p. 782.

[119] Sophie Collyer, David Harris, and Christopher Wimer, “Left Behind: The One-Third of Children in Families Who Earn Too Little to Get the Full Child Tax Credit,” Columbia Center for Poverty and Social Policy Brief Vol. 3, No.6 May 13, 2019, https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/leftoutofctc. Also see Leonard E. Burman and Laura Wheaton, “Who Gets the Child Tax Credit,” Tax Notes, October 17, 2005, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/51921/411232-Who-Gets-the-Child-Tax-Credit-.PDF, which showed that in 2005, Black and Hispanic people disproportionately could not receive the full CTC because their incomes were too low, due to the CTC’s earnings threshold and slow phase-in. Lawmakers have since lowered the CTC’s earnings threshold to enable more low-income families to claim the credit, but the CTC still locks out the lowest-income families.

[120] Chuck Marr et al., “Working Families Tax Relief Act Would Raise Incomes of 46 Million Households, Reduce Child Poverty,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 16, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/working-families-tax-relief-act-would-raise-incomes-of-46-million-households.

[121] See “Expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit Would Benefit 8 Million Black Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 8, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/expansions-of-the-earned-income-tax-credit-and-child-tax-credit-would-benefit-8; and “Expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit Would Benefit 9 Million Latino Households,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 8, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/expansions-of-the-earned-income-tax-credit-and-child-tax-credit-would-benefit-9.

[122] Using the Supplemental Poverty Measure, we estimate that the bill would reduce the overall poverty rate by 15 percent (from 14 to 12 percent) and the deep poverty rate by 17 percent (from 5 to 4 percent). It would reduce the Black poverty rate by 17 percent (from 21 to 17 percent) and the Black deep poverty rate by 20 percent (from 7 to 6 percent). It would reduce the Latino poverty rate by 20 percent (from 22 to 17 percent) and the Latino deep poverty rate by 31 percent (from 6 to 4 percent). And it would reduce the white poverty rate by 11 percent (from 10 percent to 9 percent) and the white deep poverty rate by 9 percent (from 3.9 percent to 3.5 percent).

[123] For example, the Tax Alliance for Economic Mobility, a coalition of racial justice advocates, asset-building advocates, tax reform experts, and researchers (of which CBPP is a member) has generated a number of approaches for reforming various tax expenditures to make them more effective and racially inclusive: https://www.taxallianceforeconomicmobility.org.

[124] Fischer and Huang. There are other approaches to reforming deductions that would also make them more targeted and inclusive. For example, across-the-board approaches to reforming itemized deductions and other tax expenditures, such as the Obama Administration’s proposal to limit the value of deductions to 28 cents on the dollar, could be coupled with measures to make the remaining deductions, credits, and exclusions more inclusive and accessible. One analyst, Emory University Professor Dorothy Brown, also suggests retargeting the mortgage interest deduction based on the homeowner’s race or the racial makeup of the neighborhood in which the home is owned but notes that constitutional issues may prevent the former approach.

[125] For more information on a renters’ credit, see Will Fischer, Barbara Sard, and Alicia Mazzara, “Renters’ Credit Would Help Low-Wage Workers, Seniors, and People with Disabilities Afford Housing,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 9, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/renters-credit-would-help-low-wage-workers-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities.

[126] For example, see discussion of some higher education tax expenditures at Robert Greenstein, 2015.

[127] “Financial Assets & Income,” Prosperity Now Scorecard, http://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-issue#finance/outcome/liquid-asset-poverty-rate.

[128] The bill is based on a proposal by Princeton University sociologist Kathryn Edin and others and developed by Prosperity Now. See “Congress Introduced Legislation to Help Families Save for Emergencies at Tax Time,” Prosperity Now, April 4, 2019, https://prosperitynow.org/blog/congress-introduces-legislation-help-families-save-emergencies-tax-time.

[129] Marr and Taylor.

[130] Policymakers should also pursue changes to more broadly increase the options to low- and moderate-income filers to access simple and free tax filing services. To lay a foundation for such efforts, the overall IRS budget and workforce needs to be rebuilt after being cut in real terms by 21 percent since 2010. Lawmakers should also reject proposals that would block the IRS from making simple and free tax filing more widely available. (For example, lawmakers removed from recently enacted IRS legislation a provision that would have codified the problematic “Free File” program agreement between the IRS and tax preparation companies. See: “RE: Free File First Provisions in the Taxpayer First Act of 2019 (H.R. 1957),” June 3, 2019, https://americansfortaxfairness.org/wp-content/uploads/Free-File-letter-FINAL-with-signers-6-3-19FINAL.pdf.)

[131] For example, some evidence indicates that Spanish-speaking and Latino families, particularly in rural areas, may be less aware of the EITC than some other eligible populations, although residents of areas with high concentrations of immigrants also appear to have higher EITC participation rates. Steve Holt, “The Earned Income Tax Credit at Age 30,” Brookings Institution, February 1, 2006, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-earned-income-tax-credit-at-age-30-what-we-know/.

[132] https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3151

[133] Robert Greenstein, John Wancheck, and Chuck Marr, “Reducing Overpayments in the Earned Income Tax Credit,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated January 31, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/reducing-overpayments-in-the-earned-income-tax-credit.

[134] Chuck Marr, “Private Debt Collectors a Misguided Approach for IRS,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 24, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/private-debt-collectors-a-misguided-approach-for-irs.

[135] Leachman et al.

[136] Ibid.

[137] For example, the National Consumer Law Center discusses a range of actions to reduce racial discrimination and promote responsible and equitable lending in the mortgage and broader credit markets at https://www.nclc.org/issues/credit-discrimination.html. The Department of Housing and Urban Development should also undo recent harmful steps by the Administration such as its attempt to roll back the “affirmatively furthering fair housing” rule requiring states and localities receiving federal funds through the Department of Housing and Urban Development to take meaningful steps to address racial segregation and other longstanding fair housing problems, as the 1968 Fair Housing Act requires. See Alison Bell, “HUD’s Unwarranted Rollback on Fair Housing Misreads Landmark Study,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 16, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/huds-unwarranted-rollback-on-fair-housing-misreads-landmark-study. In addition, existing voucher and tax credit programs for low-income renters can be strengthened to promote housing integration and increase opportunity for low-income renters; see, for example, Will Fischer, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Could Do More to Expand Opportunity for Poor Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 28, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/low-income-housing-tax-credit-could-do-more-to-expand-opportunity-for-poor-families; and Alicia Mazzara, “Housing Vouchers Can Do More to Move Families Into High-Opportunity Neighborhoods,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 4, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/housing-vouchers-can-do-more-to-move-families-into-high-opportunity-neighborhoods.

[138] Bell; also see Doug Ryan, David Newville, and Emanuel Nieves, “The Dismantling of the CFPB Is Leaving Vulnerable Consumers Unprotected and Supercharging the Racial Wealth Divide,” Prosperity Now, June 21, 2018, https://prosperitynow.org/blog/dismantling-cfpb-leaving-vulnerable-consumers-unprotected-and-supercharging-racial-wealth.

[139] Tax measures such as a carbon tax (with appropriate protections for lower-income households) could discourage greenhouse gas emissions and/or provide revenue for investments that also prevent or mitigate climate change. See Chad Stone, “The Design and Implementation of Policies to Protect Low-Income Households under a Carbon Tax ,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 21, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/climate-change/the-design-and-implementation-of-policies-to-protect-low-income-households, and Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “Any Federal Infrastructure Package Should Boost Investment in Low-Income Communities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated June 28, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/any-federal-infrastructure-package-should-boost-investment-in-low-income.