The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for low- and moderate-income workers has been shown to increase work, reduce poverty, lower welfare receipt, and improve children’s educational attachment.[1] University of California economist Hilary Hoynes, a leading researcher on the EITC, has written that it “may ultimately be judged one of the most successful labor market innovations in U.S. history.”[2] Concerns are often raised, however, about the EITC’s error rate, which the IRS has previously estimated at about 22 percent to 26 percent. This is clearly too high, and policymakers should take steps to reduce it, while taking account of some basic facts:

- EITC errors occur primarily because of the complexity of the rules surrounding the credit. Most of them reflect unintentional errors, not fraud. What the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) refers to as the EITC’s “improper payment rate” is not a “fraud” rate and shouldn’t be characterized as such.

- IRS studies of EITC overpayments suffer from methodological problems that likely cause them to overstate somewhat the actual EITC overpayment rate, as analysis by the IRS National Taxpayer Advocate, Nina Olson, has concluded.

- The bipartisan tax deal that Congress reached at the end of 2015 included an array of provisions to reduce error in the EITC and other refundable tax credits. Senate Finance Chairman Orrin Hatch called these program integrity measures “the most robust improvements” of their kind in nearly 20 years. Some of these provisions are still being implemented and thus are not yet fully in effect.

- As the IRS has noted to the Treasury Department’s Inspector General for Tax Administration, EITC administrative costs are very low, at less than 1 percent of the benefits provided. “[T]his is quite different from other non-tax benefits in which administrative costs related to determining eligibility can range as high as 20 percent of program expenditures,” the IRS said.[3] Testimony from IRS’ National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson suggests that if the IRS spent the equivalent of 20 percent of EITC expenditures verifying eligibility, little or no net savings would accrue even if the extra spending eliminated EITC errors altogether.[4]

The IRS has launched initiatives in recent years to reduce EITC errors. Congress can continue to help the IRS make progress in lowering EITC overpayments. Specifically, Congress can:

-

Give the IRS the needed authority to reduce EITC errors by commercial preparers. Commercial preparers file over half of all EITC returns, and the IRS has found that the majority of EITC errors occur on commercially prepared returns.[5] In 2010, the IRS launched a major initiative to require preparers who lack professional credentials to pass a competency examination to be certified to prepare tax returns. A small number of paid preparers challenged this initiative in the courts in 2013, arguing that the IRS lacks the necessary statutory authority to implement it. (Many other preparers supported the IRS initiative.)

In 2014, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia upheld a lower court’s decision in favor of the preparers who brought the suit, ruling that the IRS needed authority from Congress to implement this error-reduction initiative. Congress should promptly provide the IRS with the needed authority, as bipartisan Senate legislation[6] has proposed. This measure also was included in the Trump Administration’s 2019 budget proposal. Without it, the IRS cannot move forward with key aspects of its plan to reduce EITC overpayments resulting from preparer errors.

- Provide adequate IRS enforcement funding. Congress has cut overall IRS funding by 18 percent since 2010, adjusted for inflation. These cuts have occurred even as the IRS’s responsibilities have grown due to its role in implementing new laws (such as health reform), a significant increase in the number of tax returns filed, and growing threats such as tax-related identity theft. Cuts in the IRS budget can raise budget deficits by making it harder for the IRS to enforce compliance with the EITC rules and other areas of the tax code. Indeed, while the IRS identifies a number of questionable EITC returns through data-matching with various databases, it lacks the resources to follow up on many of those questionable claims and must pay them. Inadequate funding has also hampered the IRS from using its expanded capability under the 2015 year-end tax legislation to match information provided by employers and other institutions with information provided by filers before releasing filers’ refunds.

- Enact EITC error-reduction proposals that the Treasury Department has developed, as well as EITC simplifications that both the Bush and Obama Administrations proposed. For example, simplifying the rule governing when and how parents who are separated can claim the EITC would likely reduce errors. These and other simplification provisions are included in bills that various senators and House members have introduced.

Much of the complexity of EITC rules that leads to errors stems from EITC claims involving children, due to the intricacy of the rules regarding who can claim a child for EITC purposes in divorced, separated, and three-generation families. Errors related to who can claim a child do not affect the EITC for childless workers, the IRS Commissioner has pointed out. (The Commissioner explained that the IRS could expand the childless workers’ EITC “in a very straightforward way” because that credit is free of errors related to “where [children] live, whether you’re separated or divorced, [and] who actually has the right to claim them.”[7]) IRS research on EITC errors over 2006-2008 finds that errors involving the rules for claiming the EITC for childless workers are the least costly of overclaims.[8]

Congress has sound options to reduce EITC errors, and should avoid dubious proposals purporting to address error or fraud. In particular, lawmakers should reject measures that are primarily eligibility restrictions masquerading as error-reduction proposals — measures that cut tax credits for large numbers of working families who are honestly and accurately claiming their credits. Lawmakers should also reject proposals for onerous new paperwork and filing requirements that would deter or prevent working families from claiming credits for which they qualify.

The EITC is one of the most complex elements of the tax code that individual taxpayers face. The IRS instructions for the credit are nearly three times as long as the 15 pages of instructions for the Alternative Minimum Tax, which is widely viewed as difficult. The EITC’s complexity results in significant part from efforts by Congress to target the credit to families in need and thereby limit its budgetary cost.

EITC overpayments often result from the interaction between the complexity of the EITC rules and the complexity of families’ lives. The Treasury Department has estimated that 70 percent of EITC improper payments stem from issues related to the EITC’s residency and relationship requirements, which are complicated; filing status issues, which can arise when married couples file (often following a separation) as singles or heads of households; and other issues related to who can claim a child in non-traditional family arrangements.[9]

For example, where parents are divorced or separated, only the parent who has custody of the child for more than half of the year can claim the child for the EITC. Sometimes a non-custodial parent may erroneously claim the EITC related to that child, especially if he pays child support and thus has a perception of being eligible for the credit. For example, a non-custodial parent who pays child support may be entitled, under the terms of a divorce agreement, to claim the child as a dependent and for the Child Tax Credit; he may understandably but incorrectly assume that he can claim the child for the EITC as well.

In addition, families’ living arrangements can be complicated, with working grandparents or aunts and uncles living with working parents and their children. More than one working adult in such families may potentially qualify to claim a given child for the EITC. Neither they nor, in many cases, their tax preparers may fully understand the complex rules that determine who is entitled to claim the EITC in such circumstances. Mistakes can result.

IRS studies note that the complexity of EITC rules contributes significantly to the error rate and that fraud is not the primary factor. Analysis of IRS data by Treasury experts and studies by outside researchers suggest that most EITC overpayments do not result from intentional action by tax filers.[10]

The IRS estimated a “mid-point” EITC improper payment rate of 23.9 percent for fiscal year 2017.[11] This estimate was derived from a study based on IRS audits of a sample of tax returns for tax year 2013. If, in the course of the audit, a claimant was unable to document his or her claim to the examiner’s satisfaction, the claim was considered an overpayment. The projected amount of overclaims recovered by the IRS is subtracted from the total amount to arrive at the net estimate.

For its most recent fiscal year 2018 update, the IRS conducted a similar audit of returns for tax year 2014. When using the same estimation procedure as for 2017, the improper payment rate estimate was 23.4 percent, slightly lower than for 2017.[12]

Evidence suggests, however, that this approach overstates the error rate. Most EITC recipients cannot afford to hire lawyers or accountants to help them navigate an IRS audit, and many have trouble documenting their claim to the examiner’s satisfaction even when eligible. The IRS National Taxpayer Advocate, Nina Olson, has reported that in more than 40 percent of the cases where IRS examiners classified an EITC claim as invalid but the filer later received assistance from the Taxpayer Advocate Service (a component of the IRS that the National Taxpayer Advocate oversees) in appealing the ruling, the ruling was reversed.

Many of the EITC claimants in the recent IRS study (and most filers whom the IRS audits) did not have this assistance. Olson has testified that because the IRS studies used to estimate EITC error rates do not provide for a process of this nature, their overpayment estimates are likely overstated.

Olson also has noted that when confronted with this process, “low-income taxpayers have considerable difficulty documenting relationship and residence because of a lack of clarity from the IRS as well as their personal circumstances.” She has criticized the IRS for “inconsistency as to what documents the IRS will accept (a document may be accepted in one office but not in another) and inflexibility in accepting proof (i.e., failure to accept other types of documents where the taxpayer cannot provide standard documentation).”[13]

Two other cautions apply to the IRS estimate. First, its improper payment rate does not take a significant amount of underpayments into account.[14] For example, if a non-custodial father claims an EITC mistakenly, the father’s EITC counts as an overpayment, but the amount that the mother was eligible to claim but didn’t is not taken into account. In such cases, the actual loss to the Treasury is the net amount — the EITC that the father received minus the EITC that the mother qualified for but did not receive — rather than the gross amount the IRS study counts. (Tracking down the amount that the other parent was eligible to receive in such circumstances is beyond the scope of the IRS studies, so they cannot produce a net loss calculation.)

Second, the IRS study does not fully reflect the impact of several new enforcement measures that the IRS has implemented since 2014 (see below).

It is also worth noting that the EITC’s “refundability” (the fact that tax filers whose credit exceeds their federal income tax liability receive the difference in the form of a refund) is not the driver of overpayments. If it were, one would expect overpayments to be more common for EITCs claimed as refunds than for EITCs that simply lower the filer’s income tax liability. A sophisticated analysis by a senior Treasury economist found, however, that the overpayment rate was actually lower for EITCs claimed as refunds.[15] The National Taxpayer Advocate independently reached a similar conclusion.[16]

It is vital to reduce EITC overpayments. It should be noted, that the noncompliance rate is lower for the EITC than for various other parts of the tax code. An IRS study covering the 2008-2010 period found that business income that should have been reported on individual tax returns but was not cost the Treasury $125 billion in uncollected revenues per year, with a stunning 63 percent of sole proprietors’ income going unreported.[17] This $125 billion annual revenue loss was almost ten times the estimated annual level of EITC overclaims.[18]

The IRS has taken various steps since 2014 to reduce EITC errors. Unfortunately, it has been blocked from taking other planned steps by a court ruling that it lacks the needed legislative authority for those reforms. Congress can address this problem by providing that authority, as both President Obama’s 2017 budget and President Trump’s 2019 budget called for.

By way of background, in 2010 the IRS launched a major initiative to combat EITC errors by paid return preparers. Commercial preparers file a majority of EITC returns, and a majority of EITC overpayments occur on commercially prepared returns. Unscrupulous preparers may see an opportunity for larger fees if they can inflate a filer’s tax refund, while untrained preparers can easily make errors in preparing EITC claims. Yet hundreds of thousands of paid preparers have no obligation to meet any IRS competency standard.

The IRS reported in a study released in 2014 that “unenrolled preparers” — those who are neither attorneys, certified public accountants, nor enrolled agents — account for more than three-fourths of EITC returns prepared by a paid preparer, and that unenrolled preparers not affiliated with a national tax preparation firm “are most prone to error,” with 49 percent of the EITC returns they prepare containing errors that average 33 percent of the amount claimed. (National firms may have internal training programs and the ability to review returns before submission.)[19]

In addition, the Treasury Department reported in 2017, “About 52 percent of EITC returns are prepared by paid preparers, and most are unenrolled preparers who are not subject to professional oversight. Compliance studies show that EITC returns prepared by these unenrolled preparers have significant errors.”[20]

In contrast, volunteers in the IRS-sponsored VITA and TCE free assistance programs — which have the lowest error rates, at about 11 percent, according to the IRS’s EITC compliance study — undergo rigorous certification training and must pass a competency examination before they are allowed to prepare and file returns.

Under the IRS initiative:

- All return preparers were required to obtain a new Preparer Tax Identification Number (PTIN) to use when submitting returns to the IRS, and the IRS assembled a registry of preparers with a PTIN. This registry became fully operational for the 2012 tax filing season and helps the IRS track returns submitted by individual preparers.

- The IRS established a tax law competency examination system at the start of 2013 with the goal of requiring preparers without other professional credentials (including all unenrolled return preparers, whether or not affiliated with a national chain) to pass the test in order to be certified to file returns in the 2014 filing season.

- The IRS planned to require preparers to complete IRS-approved continuing education courses in tax law to maintain their certification in the PTIN system.

In 2013, a few individual tax preparers challenged this initiative in the courts, arguing that the IRS lacks the necessary statutory authority. In 2014, the D.C. Court of Appeals denied the IRS’s appeal of a lower court decision in the preparers’ favor. As a result, while the IRS may continue to require preparers to obtain a PTIN to use in signing tax returns, it cannot move forward with its plan to have preparers pass a competency examination, and preparers do not have to complete any continuing education courses. Congress should provide statutory authority so the IRS can act to fully implement its strategy to lower EITC errors resulting from preparer mistakes. (See box.)

In congressional testimony in February 2014, Nina Olson explained why Congress should give IRS the authority to carry out its initiative to reduce EITC overpayments by commercial preparers.*

“Simply stated, unenrolled preparers are the make-and-break point for all EITC compliance strategies. Preparers account for the majority of EITC claims submitted to the IRS, and unenrolled preparers account for three-quarters of preparer EITC returns. Unenrolled preparers have the highest error rate of all types of preparers. If a single unenrolled preparer plays fast and loose with EITC eligibility rules, tens if not hundreds of taxpayers’ returns could be in error.

“The recently strengthened regulations and increased EITC due diligence penalty under IRC § 6695(g), coupled with a robust preparer compliance initiative and vigorous preparer prosecutions, should shift some preparer compliance behavior. But so long as anyone can purchase off-the-shelf software and hang out a shingle declaring him or herself a return preparer, without any demonstration of competency or any set of ethical rules to adhere to, we will not bring about significant change in EITC compliance.

“The low income population is vulnerable to unskilled and unethical preparers. The size of the refund is attractive to payday lenders and others interested only in what fees they can charge, not to mention criminal opportunists. Preparers in this category have no professional responsibility to the tax system. Yet, as numerous studies have shown, they operate in the areas and communities where low income persons reside.a

“The single most useful step Congress can take to improve EITC compliance and reduce the Improper Payments is to enact a regulatory regime that requires unenrolled preparers who prepare returns for a fee to demonstrate minimum levels of competency by passing an initial test and then taking annual continuing education courses (including ethics).b The IRS cannot audit this EITC noncompliance out of existence — audits occur after the noncompliance has occurred and, in many instances, after the dollars have already gone out the door. Preparer regulation is prophylactic and efficient.

“More specifically, I believe Congress should explicitly authorize the IRS to require unenrolled return preparers to take a competency test and fulfill annual continuing education requirements as a condition of preparing tax returns for compensation.”

* Testimony of Nina Olson, op. cit., pp. 46-47.

a For a chilling inventory of studies showing the predatory practices and abuses in this area, see Brief of Amici Curiae, National Consumer Law Center and National Community Tax Coalition in Support of Defendants-Appellants, Loving v. Internal Revenue Service, No. 13-5061 (D.C. Cir. 2014.)

b Support for preparer regulation as a means both to protect consumers and to improve return accuracy has been broad and bipartisan. The Senate Finance Committee has twice approved legislation to authorize preparer regulation — once under former Chairman Charles Grassley (during Republican control) and once under former Chairman Max Baucus (during Democratic control). On the House side, the Ways and Means Committee has not considered preparer regulation, but its Oversight Subcommittee held a hearing in 2005 at which numerous preparer groups testified in support of such regulation. In 2010, the IRS began to implement preparer regulation on its own, but the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia invalidated the regulation as exceeding the agency’s authority in the absence of authorizing legislation. See Loving v. IRS, 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 2512 (D.C. Cir. 2014). Authorizing legislation would allow the IRS to resume the program that was underway.

Despite this setback in the courts, the IRS continues to require preparers to register and obtain PTINs. In fiscal year 2018, the IRS also identified 20,000 preparers with high error rates in the EITC claims that they filed, and it carried out a range of “real time” interventions with these preparers before and during the 2018 filing season, including educational visits by IRS agents. This strategy averted an estimated $347 million in erroneous claims, according to the IRS.[21]

The IRS also continues to issue penalties to preparers for failing to meet the basic EITC due diligence requirement, which was expanded to the Child Tax Credit and the American Opportunity Tax Credit beginning with the 2017 filing season. The number of such penalties rose in 2017, likely because some preparers weren’t cognizant of the expansion of the due diligence requirement that year and failed to comply with it. Those penalties were levied at about the same rate in 2018.

In addition to providing statutory authority for the IRS to implement its full preparer initiative, Congress should take other steps to shrink EITC overpayments.

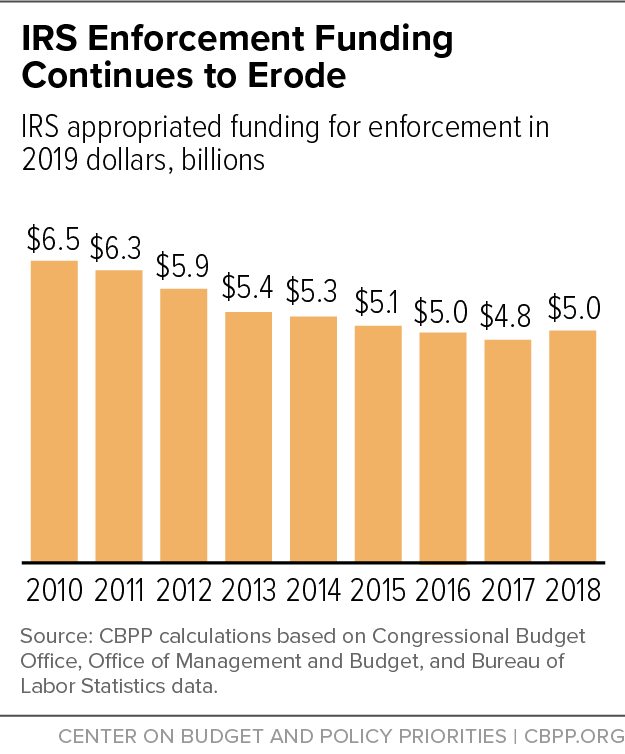

Congress should give the IRS sufficient resources to administer the tax code. IRS enforcement funding fell by 23 percent between 2010 and 2018, after adjusting for inflation (see Figure 1), forcing a 31 percent decline in the number of IRS staff devoted to enforcement — even as the number of tax returns filed grew significantly.[22]

Underfunding enforcement is penny-wise and pound-foolish. The Treasury Department estimates that each additional dollar invested in IRS tax enforcement activities yields $5.20 in increased revenue. Greater enforcement funding also produces further, indirect revenue savings by preventing erroneous refunds; Treasury has estimated those indirect savings to be about three times the direct revenue impact.[23]

These budget constraints directly affect administration of the EITC. For example, the IRS would like to expand the above-mentioned effort that averted an estimated $347 million in improper EITC and CTC claims in 2018 by identifying negligent tax preparers. But like other activities, such initiatives require adequate funding.

Inadequate funding has also hampered the IRS from using its expanded capability under tax legislation enacted in 2015 to match crucial income information (W-2s, 1099s) provided by employers and other institutions with information provided by individual filers before releasing the filers’ refunds. The IRS conducts matching with various databases and identifies questionable EITC returns before making payment. But the IRS must then resolve the questions regarding these returns in a timely fashion to avoid long delays in releasing refunds, and it lacks the staff to follow up on and resolve all of these cases within the time frame the law requires for paying tax refunds. The IRS must make payment in the remaining cases. The IRS could lower EITC errors if it had more staff to follow up promptly on more of these EITC claims. Specific issues limiting IRS capacity in this area emerged in the 2017 tax filing season, as the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported:

- Many employers failed to comply with the earlier deadline to provide W-2s, eliminating the opportunity for the IRS to conduct the matching process by February 15. According to the GAO, 260,000 employers failed to meet the new January 31 deadline, resulting in the late filing of about 7.9 million W-2s.

- Large numbers of employers — those with fewer than 250 employees — still file their W-2s on paper instead of electronically, which delayed the matching process for another 23 million W-2s.

- The Social Security Administration (SSA) initially processes the W-2s attached to tax returns and then returns the W-2s to the IRS electronically. Unfortunately, the SSA computers send the W-2s in daily batches, but IRS computers can only process them on a weekly basis. The IRS falls behind, resulting in additional large numbers of W-2s being unavailable for the matching process by February 15.[24]

Expanding the IRS’s capacity to avert improper payments thus will require increased investments in IRS staffing and computer systems rather than steadily deepening cuts in the IRS budget. (The failure of the IRS computer system on the first day of tax filing in 2018 provided further evidence of this problem.) And the growing pressure on the IRS to devote more resources to combat identity theft only tightens the squeeze on scarce IRS resources.

The 2015 tax legislation included important Treasury proposals to reduce EITC overpayments by expanding the IRS’s income-matching authority and better enabling it to administer a “due diligence strategy” related to how tax-return preparers determine eligibility for the EITC and other refundable tax credits. Return preparers must now submit a streamlined checklist of answers to eligibility questions along with any claims for the Child Tax Credit and American Opportunity Tax Credit. This expands a previous requirement that applied only to EITC claims and will improve the IRS’s ability to identify patterns of erroneous claims. And the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act further expanded the preparer due diligence requirements to include claims for head of household status. Treasury had originally proposed such measures, however, as functioning in combination with a measure enabling the IRS to require paid return preparers to pass a competency test to be certified to file returns, which Congress has not acted on.

Congress should consider additional Treasury proposals to lower tax-credit errors, which are reiterated in its latest report on EITC errors. They include:

- Providing the IRS with the statutory authority to improve accuracy on the part of paid tax-return preparers, as discussed above.

- Providing Treasury with “correctable error” authority to enable the IRS to automatically correct erroneous claims detected through reliable data sources when a tax return is filed and before a refund claim is paid. Safeguards would be required to assure that claims are not automatically rejected based on data sources that could be out of date or aren’t accurate in virtually all cases.

In addition, Congress can consider a series of EITC simplification measures that President George W. Bush’s Treasury Department proposed in the mid-2000s, after enactment of a first round of EITC simplifications in 2001 led to a 13 percent drop in overpayments. Congress never acted on these proposals, which were in several Bush budgets. Two proposals meriting particular consideration address areas where honest taxpayers can unintentionally commit errors: simplifying the complicated rules governing how parents who are separated can claim the EITC, and allowing filers who live with a qualifying child but don’t claim the child for the EITC to claim the much smaller EITC for workers not raising a child. (Current rules consider such filers to have a qualifying child even if they don’t claim the child, and regard a claim by such filers for the much smaller EITC for childless workers to be an error and an overpayment.) Treasury proposed a regulation in 2017 to correct this issue, and a final regulation is expected in 2019. Both of these meritorious Bush Treasury proposals are in legislation that was introduced in the last Congress in both the Senate and House.[25]