Costing at least $70 billion a year, the mortgage interest deduction is one of the largest federal tax expenditures, but it appears to do little to achieve the goal of expanding homeownership. The main reason is that the bulk of its benefits go to higher-income households who generally could afford a home without assistance: in 2012, 77 percent of the benefits went to homeowners with incomes above $100,000. Meanwhile, close to half of homeowners with mortgages — most of them middle- and lower-income families — receive no benefit from the deduction. Three major bipartisan panels have proposed to convert the deduction to a credit and lower the maximum amount of interest it covers. These reforms would be major improvements over current law and would generate significant additional revenue.

- A mortgage interest credit would provide more help than today’s deduction to most middle- and lower-income homeowners with mortgages, while trimming subsidies for upper-income owners. As a result, it would likely do more than the existing deduction to help families that would otherwise struggle to afford the costs of homeownership.

- Unlike simply eliminating or scaling back the deduction, which some fear would undermine the recovery in the housing market, replacing the deduction with a credit would make a major overall drop in housing prices unlikely. The credit would replace much of the deduction’s overall dollar value and would subsidize more households to purchase homes than the existing deduction. Congress could further reduce the risk of market disruption by phasing reforms in gradually.

- The proposed reforms could raise substantial added revenue — about $200 billion over ten years, under one version — and thereby contribute to a balanced deficit-reduction package. Policymakers could also use part of the savings (once deficit-reduction goals have been met) to rebalance federal housing subsidies, which disproportionately benefit higher-income homeowners despite the large unmet need for assistance among renters at the lower end of the income scale. For example, the new renters’ tax credit that CBPP has proposed, if capped at $5 billion per year, would substantially reduce housing cost burdens and the risk of homelessness and other serious hardship for 1.2 million low-income renters.[1]

Homeowners can currently deduct their interest payments on home mortgage balances up to $1 million from their taxable income. They also can deduct interest on home equity loans of up to $100,000. Within these caps, taxpayers can claim deductions on up to two homes.

The mortgage interest deduction is part of a group of deductions known as “itemized deductions,” which also include deductions for charitable giving and state and local taxes. Taxpayers can either itemize their deductions or take the standard deduction ($6,100 for singles and $12,200 for couples in 2013). Only about one-third of filers itemize their deductions.

The mortgage interest deduction is considered a “tax expenditure” or “tax subsidy” because it provides a benefit to a particular group of taxpayers; it is the most costly itemized deduction and among the largest tax expenditures.[2] The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated in January 2013 that it will reduce revenues by $70 billion in 2013 and by $379 billion over the five years from 2013 to 2017.[3]

The mortgage interest deduction is intended to encourage homeownership. Proponents of homeownership subsidies claim that expanding the number of homeowners has broader benefits for society, such as causing households to take better care of their homes and become more involved in their communities than they would if they were renters. The evidence for these claims is mixed.[4] But regardless of the benefits of expanding homeownership, the mortgage interest deduction is poorly designed to achieve this goal.

Benefits Go Mainly to Higher-Income Households

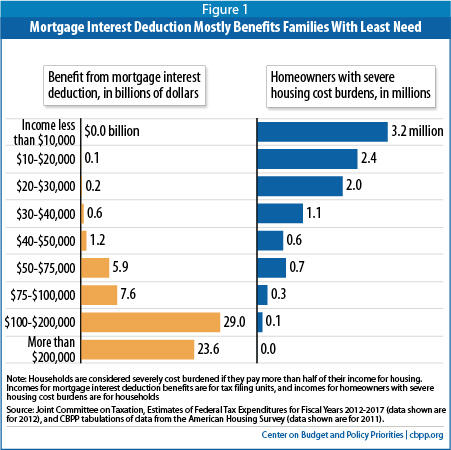

Little of the deduction’s benefits go to households that have difficulty affording a home. Data from the Census Bureau’s American Housing Survey show that in 2011, 10.5 million homeowners faced what HUD calls “severe housing cost burdens,” meaning they paid more than half of their income for housing. Some 90 percent of those homeowners (and about 40 percent of all homeowners) had incomes below $50,000, yet JCT estimates for 2012 show that homeowners with incomes below that level received only 3 percent of the benefits from the mortgage interest deduction.[5]

At the same time, 77 percent of the benefits from the mortgage interest deduction went to homeowners with incomes above $100,000, almost none of whom face severe housing cost burdens. Some 35 percent of the benefits went to homeowners with incomes above $200,000; taxpayers in this income group who claimed the deduction received an average subsidy of about $5,000.

The deduction’s benefits are concentrated among higher-income households for several reasons.

- Close to half of homeowners with mortgages — most of them middle- and lower-income families — receive no benefit from the mortgage interest deduction.[6] Some of these households do not owe federal income taxes, even though they typically pay substantial federal payroll taxes and/or state and local taxes. Others claim the standard deduction rather than itemize deductions.

- Homeowners with higher incomes tend to have more expensive homes and thus more mortgage interest to deduct.

- The deduction’s value depends on a household’s marginal tax rate, so households in higher tax brackets benefit more. To see why, consider this example of two households. An investment banker making $675,000 who has a $1 million mortgage and pays $40,000 in mortgage interest each year receives a housing subsidy of about $14,000 annually from the mortgage interest deduction. The banker pays about 65 cents per dollar of mortgage interest, and the taxpayers pick up the remaining 35 cents.[7] By contrast, a schoolteacher making $45,000 and paying $10,000 a year in mortgage interest on a more modest home receives a housing subsidy worth $1,500 annually. Here, the family pays 85 cents of every dollar of mortgage interest and taxpayers pick up 15 cents. The banker’s subsidy is not only larger than the teacher’s in dollar terms, but also represents a greater shareof the banker’s mortgage interest expenses.

In a major paper on the structure of tax incentives, tax experts Lily Batchelder, Fred Goldberg, and Peter Orszag wrote that providing larger benefits to higher-income households “is economically inefficient unless policymakers have specific knowledge that such households are more responsive to the incentive or that their engaging in the behavior generates larger social benefits.”[8] In the case of the mortgage interest deduction, these conditions are unlikely to hold.

Higher-income households are more likely to be deciding how expensive a home to buy or how large a mortgage balance to maintain than whether to buy a home at all. Meanwhile, lower- and middle-income households, who are more likely to be on the margin between buying and renting a home, receive a much more modest benefit (or no benefit at all) from the deduction.

In addition, the deduction is poorly suited to help struggling homeowners keep their homes. Homeowners whose incomes decline will receive a smaller subsidy if they fall into a lower marginal tax bracket. And homeowners whose incomes drop to the point where they owe no federal income tax that year (for example, because they lose their jobs) would lose the value of their deduction altogether, precisely when they are most likely to have difficulty making mortgage payments.

Researchers who have studied variations in the value of the mortgage interest deduction over time and across states have generally concluded that it has little overall impact on homeownership.[9] International comparisons raise further doubts about claims that the deduction is a major factor driving homeownership rates. As the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has noted, “Despite the favorable tax treatment that mortgage interest receives in the United States, the rate of homeownership here is similar to that in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, and none of those countries currently offers a tax deduction for mortgage interest.”[10] The United Kingdom phased out its mortgage interest deduction from 1975 to 2000, but the share of households that own homes rose from 53 percent in 1974 to 68 percent in 2001.[11]

In addition to doing little to promote homeownership, the mortgage interest deduction creates incentives that may cause significant harm in other areas. For example, the deduction lowers taxes on investment in owner-occupied housing relative to business investments, potentially skewing the allocation of capital across the economy. According to the report of a tax reform panel established by President George W. Bush:

This may result in too little business investment, meaning businesses purchase less new equipment and fewer new technologies than they otherwise might. Too little investment means lower worker productivity, and ultimately, lower real wages and living standards.[12]

In addition, because the deduction is based on interest on debt, it discourages taxpayers from paying down mortgage balances when they have funds available to do so. Larger mortgage balances in turn increase the risk that households will be unable to pay their mortgages if their incomes drop or will be left with negative equity (that is, with mortgage debt larger than the value of the home) if house prices decline.

A number of proposals would scale back or reform the mortgage interest deduction. Some would limit other itemized deductions as well. For example, as discussed in the box on page 9, the Obama Administration has proposed to cap the tax subsidy from the mortgage interest deduction and other itemized deductions at 28 cents on the dollar. This would trim deductions for higher-income households (that is, those who face tax rates above 28 percent) while leaving deductions for most taxpayers unchanged. As a relatively modest adjustment to the mortgage interest deduction, compared to the proposals described below, the proposal would do less to address the deduction’s flaws. But it would make the deduction somewhat more equitable and raise significant revenue.

In its biennial reports on options for reducing the deficit, CBO has included a phase-out of the mortgage interest deduction without any homeownership subsidy to replace it.[13] Another proposal, by Brookings Institution economists, would replace the deduction with a narrowly targeted, one-time credit for first-time homebuyers.[14] These two proposals would generate large amounts of revenue and essentially remove the current deduction’s incentives for debt and overinvestment in housing. But they would also eliminate tax benefits for large numbers of middle-income homeowners and be very difficult politically to enact.

Several recent proposals have focused on another approach to reform: converting the deduction to a tax credit for mortgage interest, reducing the amount of interest it covers, and making second homes ineligible. Such proposals have been part of various bipartisan plans, including those proposed by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, co-chairs of the President’s fiscal commission; the debt reduction panel headed by former CBO and OMB director Alice Rivlin and former Senator Pete Domenici; and President Bush’s tax reform panel. A similar proposal was also featured in a recent paper by Alan Viard of the American Enterprise Institute.[15] Representative Keith Ellison (D-MN) introduced legislation in March 2013 that would make changes along the same lines, though it would continue to permit subsidies for second homes.[16]

Table 1

Comparison of Mortgage Interest Credit Proposals |

| Proposal | Limit on Interest Covered | Credit Percentage | Credit for Second Homes? | Type of Credit |

| Bush Tax Reform Panel | Interest on mortgages up to 125 percent of median price in area | 15 percent | No | Non-Refundable Owner-Claimed |

Rivlin-Domenici

Commission | $25,000 | 15 percent | No | Lender-Claimed |

| Bowles-Simpson Illustrative Plan | Interest on mortgages up to $500,000 | 12 percent | No | Non-Refundable Owner-Claimed |

| Ellison Bill | Interest on mortgages up to $500,000 | 15 percent | Yes | Non-Refundable Owner-Claimed |

| Viard Paper | Interest on mortgages up to $300,000 | 15 percent | No | Refundable Owner-Claimed |

These credit-based proposals would improve upon the existing deduction in a number of ways. A credit, unlike a deduction, would benefit homeowners whether they itemize or claim the standard deduction. And the tax benefit, rather than varying based on a household’s marginal tax rate, would be a fixed percentage of the household’s mortgage interest. This would shrink benefits for households in higher tax brackets but expand them or leave them unchanged for households in the lower brackets.

Reducing the maximum amount of interest that the credit covers would further scale back subsidies for better-off households (since they tend to have larger mortgages), but depending on where the maximum level is set, would not affect most homeowners. For example, the Bowles-Simpson illustrative tax reform plan would provide a credit for interest on mortgage balances up to $500,000, half the current cap. In 2009, data from the American Housing Survey indicate that 90 percent of homeowners with mortgages had balances below $300,000.

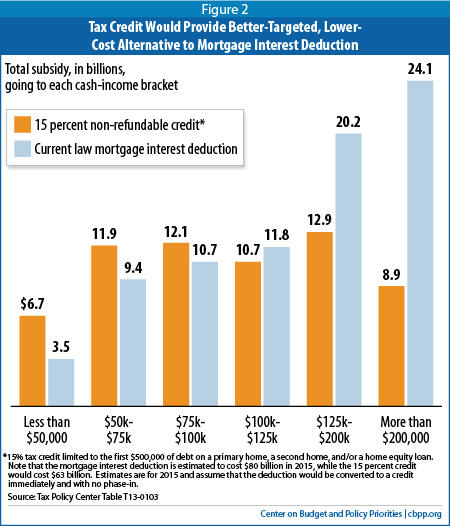

Taken together, these changes would trim benefits significantly for higher-income households while modestly increasing them well down the income scale. The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimates that a 15 percent credit that covers mortgages up to $500,000 and is non-refundable (that is, available only to households with federal income tax liability) would reduce annual subsidies by $24 billion (42 percent) among homeowners with incomes above $100,000.

[17] Of that $24 billion in savings, about two-thirds would come from homeowners with incomes over $200,000.

Meanwhile, a credit like this would help 16 million more homeowners than the existing deduction and increase subsidies by $7 billion (30 percent) overall among homeowners with incomes under $100,000. As a result, the credit would do as much or more than retaining the mortgage interest deduction to help households who would otherwise have difficulty affording the costs of homeownership or be on the margin between owning and renting.

The Rivlin-Domenici commission proposed replacing the mortgage interest deduction with a credit that the lender would claim and pass through to the homeowner in the form of a lower interest rate. (In contrast, homeowners claim the existing mortgage interest deduction and would claim the other proposed mortgage interest credits.) This feature would make the credit simpler for homeowners, since they would no longer have to claim mortgage interest on their returns or provide a form from their lender as verification.[18]

Also, because the credit’s benefit would be delivered though a reduced interest rate, it would be available to households even if they did not have tax liability in a given year (for example, because a family member lost a job). By contrast, the Bowles-Simpson, Bush panel, and Ellison proposals all call for non-refundable, owner-claimed credits that would only be available to households with tax liability. The Rivlin-Domenici proposal (and the Viard proposal, which calls for a refundable owner-claimed credit) would consequently be more effective at helping families who have encountered hard times and are struggling to keep their homes.

TPC estimates indicate that more than 10 million homeowners, the great majority with incomes below $50,000, would benefit from a lender-claimed credit but not from a non-refundable owner-claimed credit.[19] Because it would reach more homeowners, changing the current deduction to a lender-claimed credit would raise less revenue than conversion to a non-refundable owner-claimed credit; alternatively, the credit would have to be set at a lower percentage to raise the same amount of revenue.

Major reform of the mortgage interest deduction would be more likely to occur as part of a comprehensive effort to make the tax code more effective and equitable and reduce deficits than as a separate measure. Both the Rivlin-Domenici and Bowles-Simpson proposals for conversion of the deduction to a credit were part of broader plans to eliminate or restructure itemized deductions generally and other major tax expenditures, many of which also are poorly targeted or designed.

With the mortgage interest deduction converted to a credit, the number of taxpayers who itemize deductions would be reduced, since some taxpayers would receive a greater benefit from the standard deduction than from their remaining itemized deductions. That, in turn, could have the unintended side effect of lowering incentives to give to charity, since taxpayers using the standard deduction receive no added tax benefit for charitable donations. The impact on donations likely would be modest, however. Households with sizeable charitable donations would generally still claim itemized deductions, since the value of their charitable deductions together with other deductions (such as for state and local taxes) would still exceed the standard deduction.

Alan Viard of the American Enterprise Institute notes that any potential impact on incentives for charitable giving could be further limited by reducing the standard deduction at the same time the mortgage interest deduction is converted to a credit, while also raising the personal exemption or taking other measures to avoid raising taxes on families with modest incomes. Similarly, the Bowles-Simpson and Rivlin-Domenici plans called for converting the deduction for charitable giving into a credit as well as for changes to other tax expenditures.

While House and Senate committees are now examining options for comprehensive tax reform, changes to tax expenditures outside of comprehensive tax reform may also be considered, given policymakers’ focus on deficit reduction. During last year’s budget negotiations and during the presidential campaign, members of both parties expressed interest in some form of across-the-board limit on tax expenditures. Such a limit would treat a number of tax expenditures in a similar fashion and obviate the need for Congress to agree on reforms to individual tax provisions.a

A well-designed limit on tax expenditures could be a sound first step toward restructuring the mortgage interest deduction as a credit (and restructuring other tax expenditures). Of the various proposals to date, the President’s proposal to limit the value of itemized deductions and certain other tax expenditures to 28 cents on the dollar has the soundest design. It would reduce, although not eliminate, inefficiencies resulting from high-income taxpayers receiving a larger subsidy per dollar of mortgage interest than low- and middle-income taxpayers.

a See Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Joel Friedman, “Tax Expenditure Reform: An Essential Ingredient of Needed Deficit Reduction,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 27, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3912.

Some have expressed concern that eliminating or scaling back the mortgage interest deduction could push house prices down and undercut the housing recovery by reducing incentives for families to purchase homes. Replacing the deduction with a credit would not likely lead to a major overall price decline, however, since the credit would help more households than the deduction and would replace much of the deduction’s total dollar value — for example, about four-fifths under a 15 percent non-refundable credit covering interest on mortgages up to $500,000.

Conversion to a credit could cause prices for higher-cost homes to be somewhat lower than they would be otherwise, reducing sales proceeds for current owners — although as a recent Urban Institute report based on input from a roundtable of housing researchers and policy experts noted, factors such as today’s low interest rates and low house prices relative to rents would dampen the impact of reforms on prices.[20] Moreover, since conversion to a credit would expand subsidies for low- and moderate-income households, it would be highly unlikely to push prices down for the middle- and low-priced homes that such families tend to purchase. Indeed, the Urban Institute report concluded that “proposals that shift the MID to benefit low- and moderate-income buyers could actually stabilize and increase prices of lower-priced homes, whose values continue to lag.”

Congress could further reduce the risk that reforming the mortgage interest deduction would disrupt housing markets by phasing in the conversion. The Bush panel, for example, proposed phasing it in over five years, while Viard proposed a phase-in over nine years.

Savings Could Reduce Deficit and Rebalance Federal Housing Policy

Reforming the mortgage interest deduction along the lines described above would generate additional revenue, since the savings from subsidy reductions for higher-income households would more than offset the costs of the increased benefits for middle- and lower-income households. TPC estimates, for example, that a 15 percent non-refundable credit covering interest on mortgages up to $500,000 would raise $200 billion over ten years if it were phased in gradually over the first five years.[21] The amount raised would vary depending on the credit’s parameters, but all of the major reform proposals would generate a large amount of added revenue. As a result, conversion to a credit could make a substantial contribution to reducing the deficit.

Policymakers also could use part of the savings to help low-income renters who are struggling to afford housing. More than three-fourths of federal housing subsidies go to homeowners, even though renters — who make up more than one-third of the population — are far more likely to pay a very high share of their income for housing or face other serious housing-related problems.

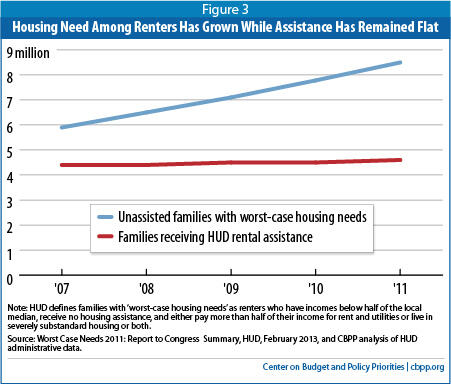

Rigorous research has shown that rental assistance such as Section 8 vouchers sharply reduces homelessness and housing instability, conditions that have a long-term impact on children’s health and development. If combined with supportive services, rental assistance can also help modest-income people who are elderly or have disabilities to retain their independence and avoid (or delay) entry into more costly institutional care facilities. But due to funding limitations, federal rental assistance programs only reach one in four eligible lower-income families, and the extent of unmet need has risen sharply.[22] In 2011, 8.5 million renter households with no housing assistance and incomes below half of the median income in their area faced what HUD terms “worst-case housing needs,” meaning that they paid more than 50 percent of the their incomes for rent and utilities or lived in severely substandard housing. This was an increase of 2.6 million households, or 43 percent, from 2007.[23]

Along with their deficit-reduction goals, policymakers could direct a modest portion of the added revenues from reform of the mortgage interest deduction or other tax reform — perhaps $5 billion a year — to address part of this unmet need, for example by establishing a new tax credit to help the lowest-income renters afford housing.[24] In its February 2013 report, the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Housing Commission expressed support for such a shift, recommending that “a portion of any revenue generated from changes in tax subsidies for homeownership should be devoted to expanding support for rental housing programs for low-income populations in need of affordable housing.”[25]

The mortgage interest deduction costs the federal government at least $70 billion a year but is not well designed to further its purpose of promoting homeownership. Converting the deduction to a credit would do more to support homeownership while also generating substantial revenues and making the tax code fairer. Those revenues could reduce the deficit and help address unmet needs for assistance with housing costs among modest-income owners and renters. In developing tax reform proposals, policymakers should give such a conversion serious consideration.