Health Care Lifeline: The Affordable Care Act and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Testimony of Aviva Aron-Dine, Vice President for Health Policy, CBPP

Before the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health

End Notes

[1] Kaiser Family Foundation analysis, drawing on data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, shows a 1.3 percent drop in fully insured group market coverage from March through June. If extrapolated to the full market, that would imply a roughly 2 million drop in employer coverage, though coverage losses among workers at self-insured firms may have been smaller. Urban Institute analysis of Census Household Pulse survey data shows a 3.3 million drop in job-based coverage from late April/early May through July, although the underlying data are quite noisy. The drop in job-based coverage is likely to grow over time, because people who lose their jobs do not always immediately lose their coverage and because a larger share of early job losses during the pandemic were temporary layoffs, while a larger share of subsequent job losses were permanent. Even so, coverage losses may be smaller than some initially expected, because job losses in the recession to date have been unusually concentrated among low-wage workers who did not have coverage to start with. See Cynthia Cox and Daniel McDermott, “What Have Pandemic-Related Job Losses Meant for Health Coverage?” Kaiser Family Foundation, September 11, 2020, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/what-have-pandemic-related-job-losses-meant-for-health-coverage/ and Anuj Gangopadhyaya, Michael Karpman, and Joshua Aarons, “As the COVID-19 Recession Extended into the Summer of 2020, More Than 3 Million Adults Lost Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Coverage and 2 Million Became Uninsured,” Urban Institute, September 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102852/as-the-covid-19-recession-extended-into-the-summer-of-2020-more-than-3-million-adults-lost-employer-sponsored-health-insurance-coverage-and-2-million-became-uninsured.pdf.

[2] These calculations are based on the National Health Interview Survey.

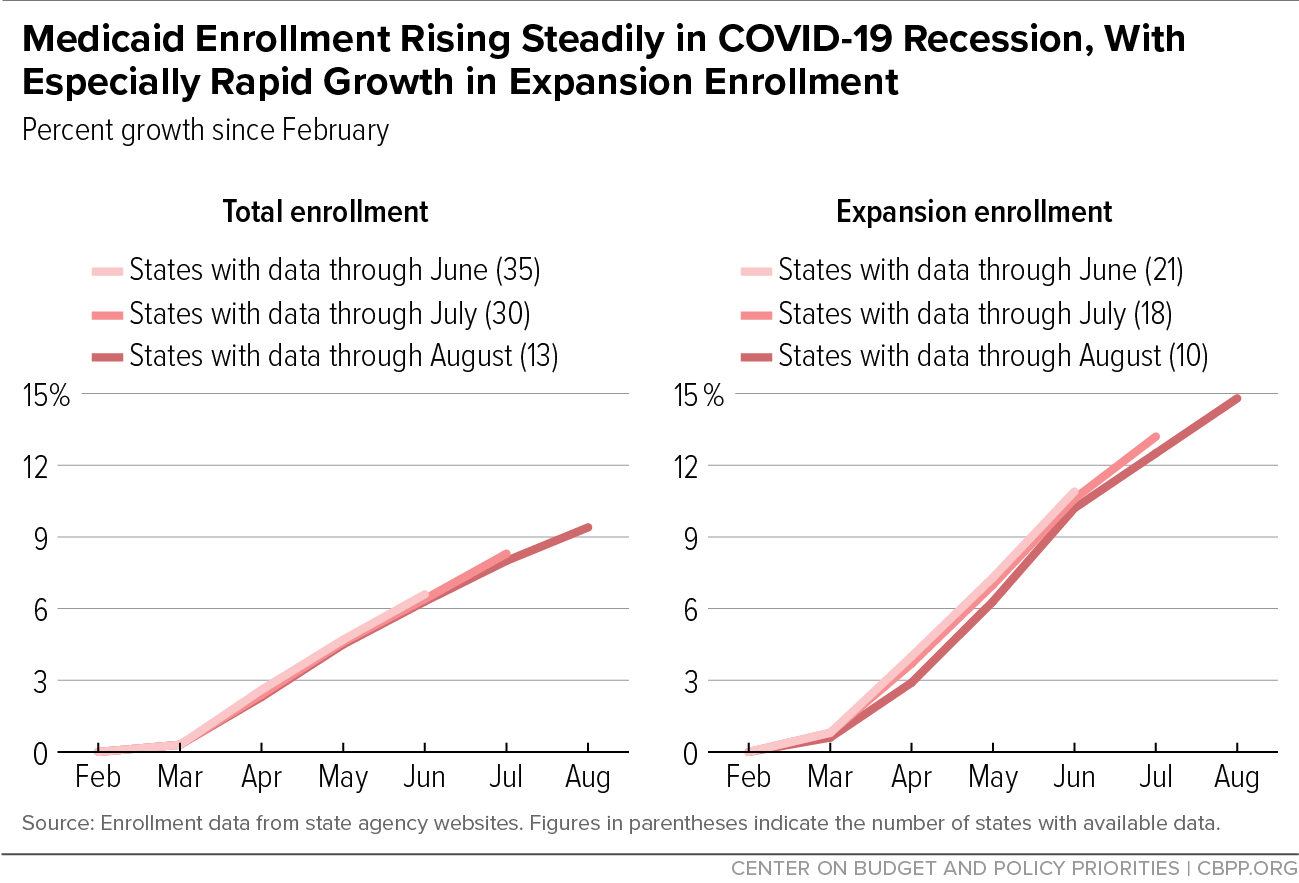

[3] These figures update those published in Matt Broaddus, “Medicaid Enrollment Continues to Rise,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 9, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-enrollment-continues-to-rise. Methodology and sources can be found in Aviva Aron-Dine, Kyle Hayes, and Matt Broaddus, “With Need Rising, Medicaid Is At Risk for Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 22, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/with-need-rising-medicaid-is-at-risk-for-cuts.

[4] Sarah Lueck and Matt Broaddus, “Emergency Special Enrollment Period Would Boost Health Coverage Access at a Critical Time,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 30, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/emergency-special-enrollment-period-would-boost-health-coverage-access-at-a-critical.

[5] Of the established federal health insurance surveys, the first data on post-pandemic coverage will come from the National Health Interview Survey, which generally releases second-quarter estimates in mid-November. While the Census Household Pulse survey (a new survey introduced during the pandemic) provides an initial glimpse at trends since late April/early May, the health coverage numbers in the new survey have fluctuated significantly from week to week. However, the Urban Institute analysis of these data referenced above does find that increases in public coverage have offset well over half the loss in job-based coverage among adults in states that have expanded Medicaid, which is a larger share than for adults nationwide during the Great Recession.

[6] An April Gallup survey found that 14 percent of Americans would forgo care for COVID-19 symptoms due to cost, with higher percentages for groups with higher uninsured rates. Dan Witters, “In U.S., 14% With Likely COVID-19 to Avoid Care Due to Cost,” Gallup, April 28, 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/309224/avoid-care-likely-covid-due-cost.aspx.

[7] Michael Simpson, “The Implications of Medicaid Expansion in the Remaining States: 2020 Update,” Urban Institute, June 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102359/the-implications-of-medicaid-expansion-in-the-remaining-states-2020-update_0.pdf.

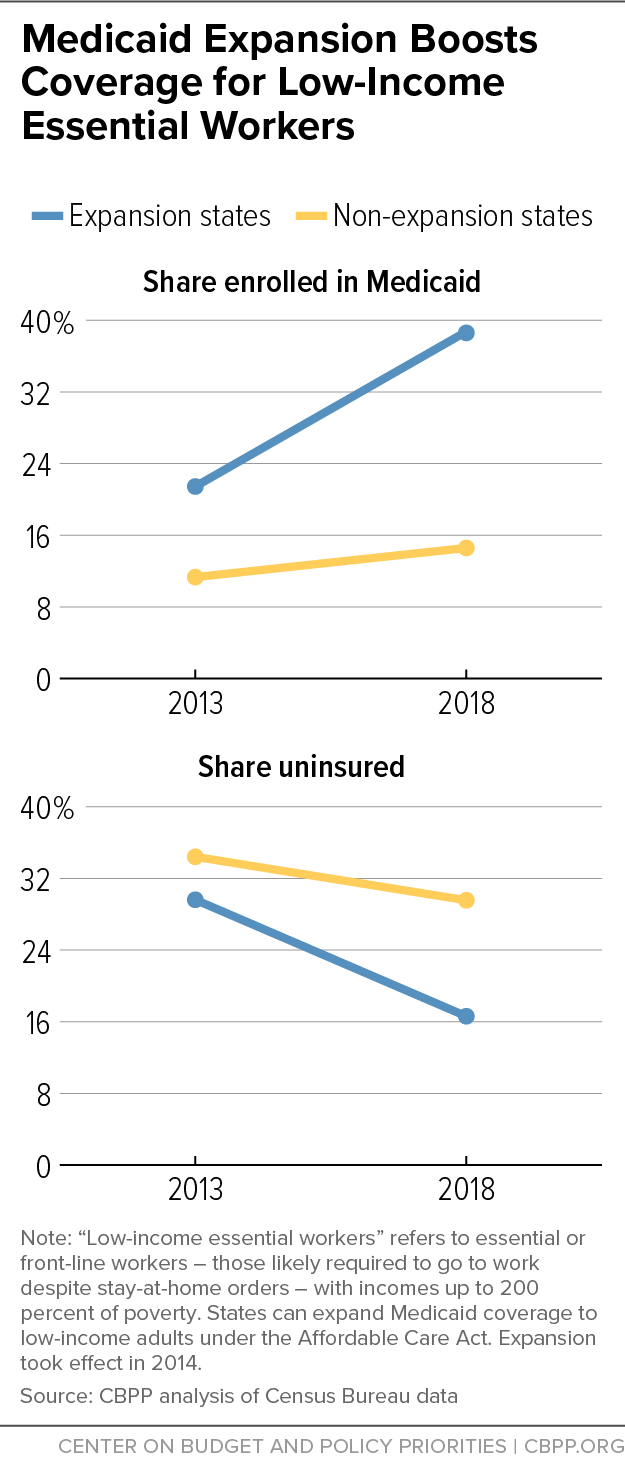

[8] For an explanation of how we define low-income essential workers, see Jesse Cross-Call and Matt Broaddus, “States That Have Expanded Medicaid Are Better Positioned to Address COVID-19 and Recession,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 14, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-that-have-expanded-medicaid-are-better-positioned-to-address-covid-19-and.

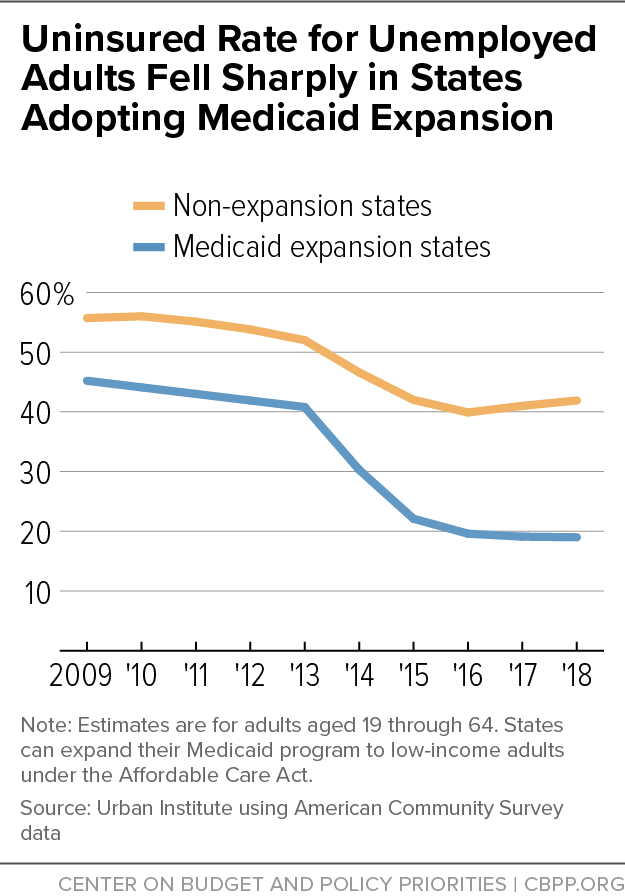

[9] Anuj Gangopadhyaya and Bowen Garrett, “Unemployment, Health Insurance, and the COVID-19 Recession,” Urban Institute, April 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101946/unemployment-health-insurance-and-the-covid-19-recession_1.pdf.

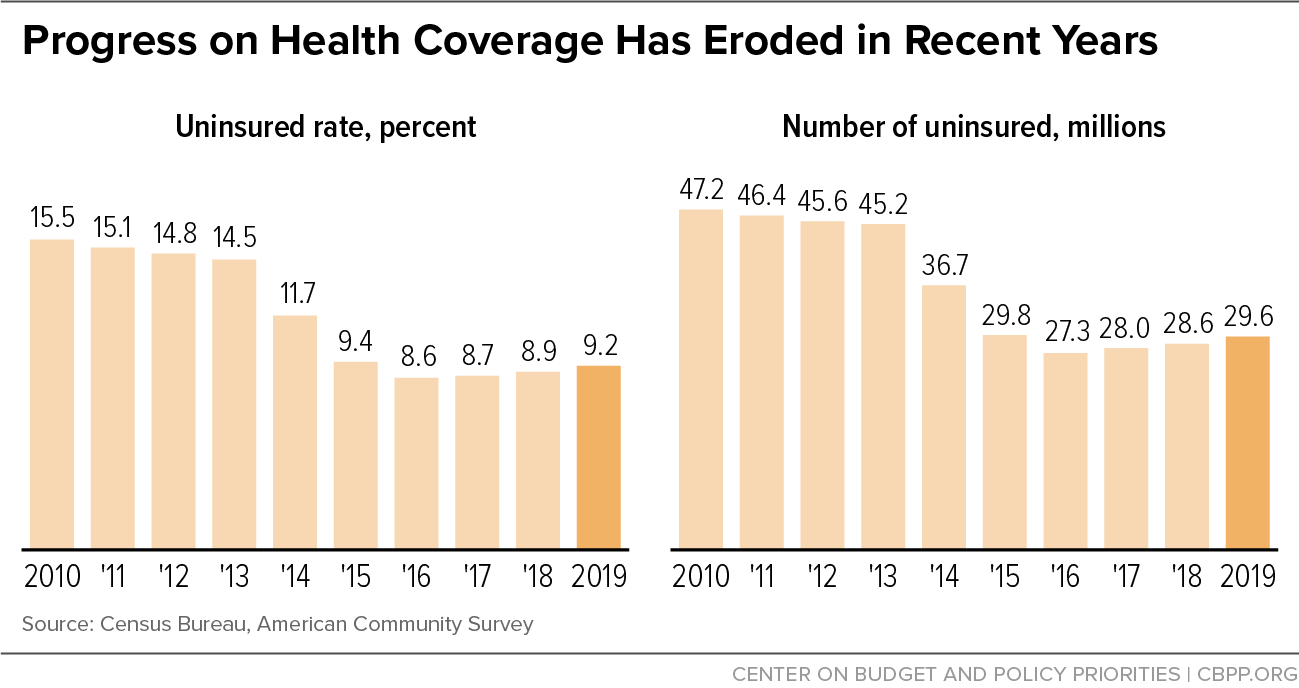

[10] For additional discussion, see Matt Broaddus and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Uninsured Rate Rose Again in 2019, Further Eroding Earlier Progress,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 15, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/uninsured-rate-rose-again-in-2019-further-eroding-earlier-progress.

[11] See for example Hamutal Bernstein, Dulce Gonzalez, Michael Karpman, and Stephen Zuckerman, “Amid Confusion over the Public Charge Rule, Immigrant Families Continued Avoiding Public Benefits in 2019,” Urban Institute, May 18, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/amid-confusion-over-public-charge-rule-immigrant-families-continued-avoiding-public-benefits-2019.

[12] For further discussion, see Matt Broaddus, “Research Note: Medicaid Enrollment Decline Among Adults and Children Too Large to Be Explained by Falling Unemployment,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 17, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-enrollment-decline-among-adults-and-children-too-large-to-be-explained-by and Samantha Artiga and Olivia Pham, “Recent Medicaid/CHIP Enrollment Declines and Barriers to Maintaining Coverage,” Kaiser Family Foundation, September 24, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/recent-medicaid-chip-enrollment-declines-and-barriers-to-maintaining-coverage/.

[13] See for example, Lexi Churchill, “The Trump Administration Cracked Down on Medicaid. Kids Lost Insurance,” Pro Publica, October 31, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/the-trump-administration-cracked-down-on-medicaid-kids-lost-insurance.

[14] Jacob Goldin, Ithai Z. Lurie, and Janet McCubbin, “Health Insurance and Mortality: Experimental Evidence from Taxpayer Outreach,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26533, December 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26533.

[15] See Sarah Lueck and Matt Broaddus, “Emergency Special Enrollment Period Would Boost Health Coverage Access at a Critical Time,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 30, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/emergency-special-enrollment-period-would-boost-health-coverage-access-at-a-critical.

[16] Abby Goodnough, “Trump Program to Cover Uninsured COVID-19 Patients Falls Short of Promise,” New York Times, August 29, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/29/health/Covid-obamacare-uninsured.html.

[17] For background on the lawsuit, see Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Suit Challenging ACA Legally Suspect But Threatens Loss of Coverage for Tens of Millions,” updated August 21, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/suit-challenging-aca-legally-suspect-but-threatens-loss-of-coverage-for-tens-of.

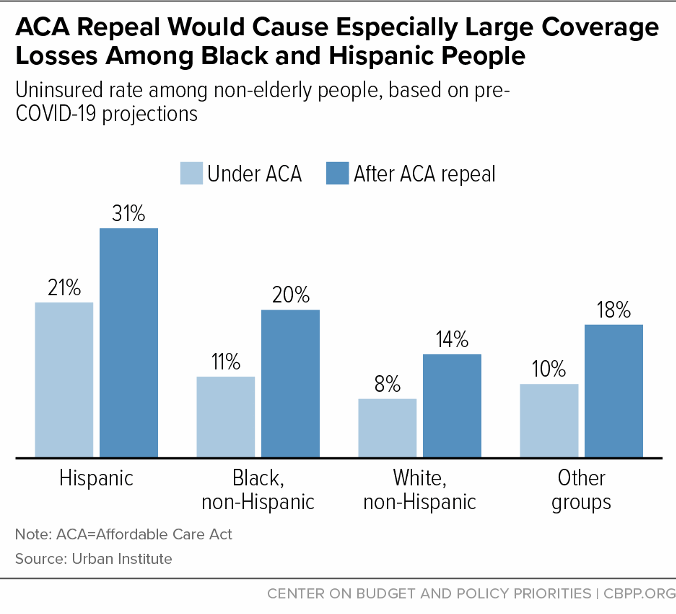

[18] Jessica Banthin et al., “Implications of the Fifth Circuit Decision in Texas v. United States,” Urban Institute, December 2019, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101361/implications_of_the_fifth_circuit_court_decision_in_texas_v_united_states_final_121919_v2.pdf.

[19] For additional discussion, see Tara Straw and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Commentary: ACA Repeal Even More Dangerous During Pandemic and Economic Crisis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 24, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/health/commentary-aca-repeal-even-more-dangerous-during-pandemic-and-economic-crisis

[20] These policies are, of course, not the only reasons for these states’ low uninsured rates, but examining the policies the states have in common is still instructive.

[21] Massachusetts and Vermont provide additional financial assistance to lower-income marketplace consumers; D.C. extends Medicaid eligibility above 138 percent of the poverty line; and Minnesota and New York provide more affordable coverage to lower-income people through Basic Health Programs. Hawaii, meanwhile, has more stringent requirements for employers to offer coverage than apply nationally under the ACA.

[22] For a discussion of Massachusetts’ approach and implications for federal policy, see Sarah Lueck, “Proposed Change to ACA Enrollment Policies Would Boost Insured Rate, Improve Continuity of Coverage,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 5, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/proposed-change-to-aca-enrollment-policies-would-boost-insured-rate-improve.

[23] Jessica Schubel, “States Are Leveraging Medicaid to Respond to COVID-19,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated September 2, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-leveraging-medicaid-to-respond-to-covid-19.

[24] See, for example, Lucy Dadayan, “State Tax Revenues Surged in July 2020, But Cumulatively Are Down During COVID-19 Period,” Urban Institute, September 16, 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2020/09/16/monthlystrh_july2020.pdf and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “States Grappling with Hit to Tax Collections,” updated August 24, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-grappling-with-hit-to-tax-collections.

[25] Aviva Aron-Dine et al., “Larger, Longer-Lasting Increases in Federal Funding Needed to Protect Coverage,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 5, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/larger-longer-lasting-increases-in-federal-medicaid-funding-needed-to-protect.

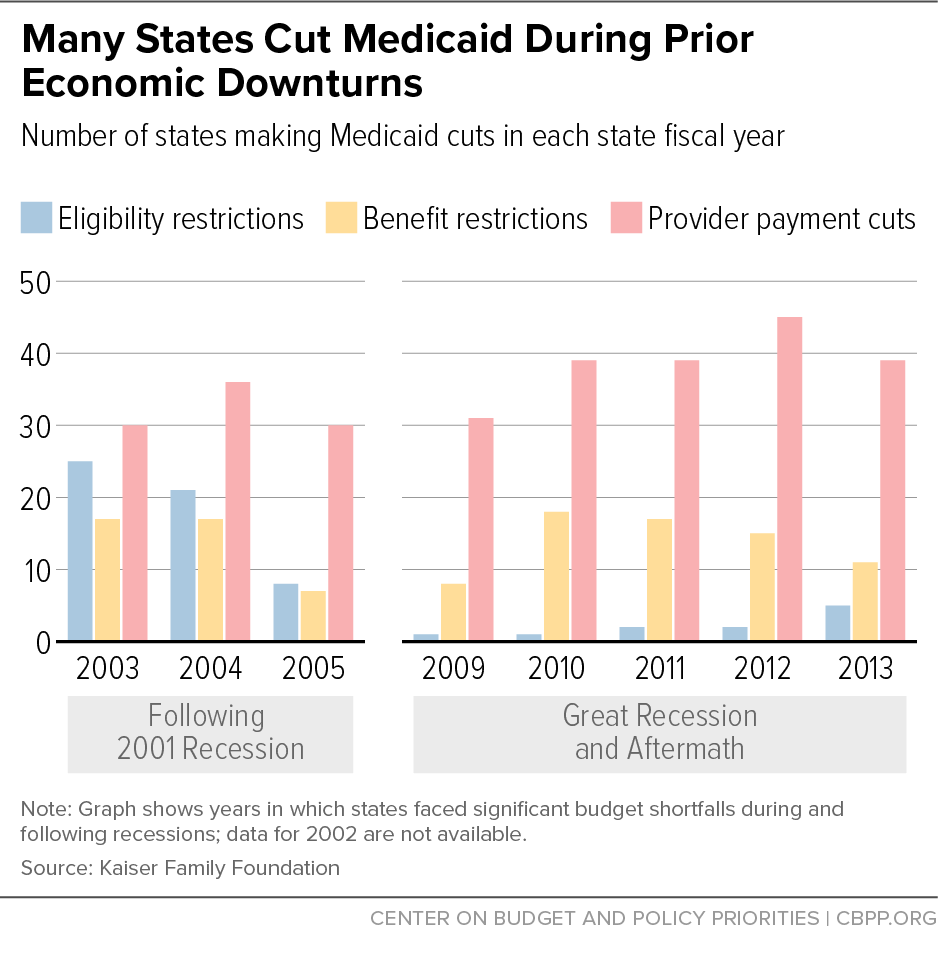

[26] A similar rule in place during the Great Recession explains why far fewer states restricted eligibility during the Great Recession than during the shallower recession of the early 2000s, as shown in Figure 6. Aviva Aron-Dine, “Medicaid ‘Maintenance of Effort’ Protections Crucial to Preserving Coverage,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 13, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-maintenance-of-effort-protections-crucial-to-preserving-coverage.

[27] Judith Solomon, “Continuous Coverage Protections in Families First Act Prevent Coverage Gaps by Reducing ‘Churn,’” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 16, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/continuous-coverage-protections-in-families-first-act-prevent-coverage-gaps-by.

[28] Aviva Aron-Dine, Kyle Hayes, and Matt Broaddus, “With Need Rising, Medicaid Is at Risk for Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 22, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/with-need-rising-medicaid-is-at-risk-for-cuts.