A bill recently introduced in the Senate, the Consumer Health Insurance Protection Act (S. 1213), includes a provision similar to a policy already in place in Massachusetts that would allow lower-income people to enroll in marketplace coverage at any time during the year.[1] Evidence suggests that in Massachusetts, making it easier for people to enroll in the marketplace (in combination with other policies the state has adopted) has helped boost enrollment, prevent coverage gaps, and reduce uninsured rates, all without causing significant adverse selection.

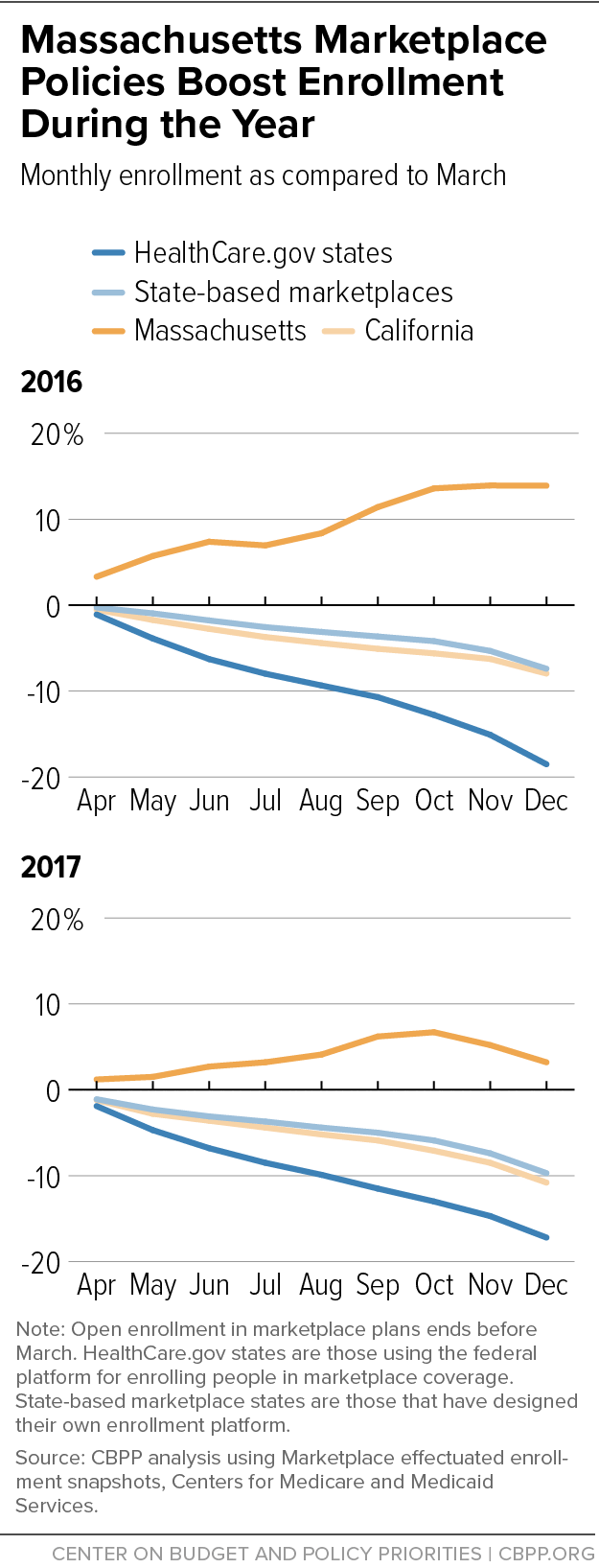

In virtually all states, enrollment in the health insurance marketplace declines during the year, as people leaving marketplace plans outnumber those who join after the annual open enrollment period has ended. But in Massachusetts, the pattern is strikingly different. Enrollment in the Massachusetts Health Connector, as the state-run marketplace is known, actually increases during the year. (See Figure 1.)

One important factor: many lower-income people in Massachusetts can enroll in marketplace coverage at any point during the year, even if they would not qualify for a special enrollment period (SEP) in other states. SEPs allow people to enroll in the marketplace after the annual open enrollment period has ended if they experience events such as losing other health coverage or having a baby. In Massachusetts, a person can also enroll in a marketplace plan outside of open enrollment if they can demonstrate income up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level (about $75,000 for a family of four or $36,000 for an individual), are new to ConnectorCare (the state program available to people with incomes up to 300 percent of poverty), and are otherwise eligible to receive premium subsidies.[2] They don’t have to experience, or document, any other event that triggers an SEP.

This approach to enrollment is just one of the likely reasons for Massachusetts’ unique enrollment pattern. Notably, the state provides additional subsidies, on top of the federal premium tax credit and cost-sharing reductions established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), to people up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level, the same group eligible for enrollment throughout the year. In addition, Massachusetts has integrated its eligibility systems for Medicaid and the Health Connector, so that when someone loses Medicaid eligibility, they can enroll in a Health Connector plan quickly and with very little additional effort. The state also conducts outreach to consumers throughout the year, not just during the annual open enrollment period (which, at nearly three months, is longer than the federal period), and its longstanding requirement for individuals to have coverage or pay a penalty (in place since 2006) has fostered an expectation that people will seek coverage.

Massachusetts’ approach appears to significantly affect enrollment. Figure 1 shows the typical pattern in marketplace enrollment — a decline during the months after the open enrollment period has ended. Enrollment in state-based exchanges tends to decline less than in states using the HealthCare.gov platform, but it still falls markedly.

For example, California’s state marketplace, Covered California, has invested heavily in outreach and marketing and has achieved stronger rates of enrollment among eligible consumers and a healthier risk pool compared to many states with a federally run marketplace.[3] But Covered California enrollment still wanes during the year. In Massachusetts, in contrast, Health Connector enrollment data show a consistent pattern of growth during 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018, with more people added to Connector coverage than left it in most months.[4] In Massachusetts, about one-third of monthly enrollments are people coming from Medicaid, while two-thirds are coming from elsewhere.

It’s not surprising that reducing paperwork barriers contributes to higher enrollment and fewer coverage gaps.

Enrolling through an SEP is challenging. People must first understand that they are eligible for an SEP, and many do not. Then, they must apply by the deadline, which is usually 60 days after the SEP-triggering event.

SEP enrollment in individual-market coverage also frequently requires people to submit documentation to prove they experienced the event, which can deter enrollment. [5] In the last few years, the federal government has restricted SEP eligibility and added documentation requirements for HealthCare.gov applicants. Now, most people who attempt to access an SEP must obtain and submit paperwork showing that they experienced the SEP-triggering event. For example, someone who loses a job with employer-sponsored health benefits must submit a letter from an employer documenting the coverage loss, generally within 30 days, before they can enroll in a marketplace plan.

Overly burdensome documentation requirements discourage people from obtaining benefits for which they are eligible, a fact shown in research and well established by experience with eligibility and enrollment rules in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. In the federal marketplace, SEP plan selections dropped almost 15 percent in 2016, compared to the same period in 2015, after the Obama Administration began directing people enrolling through the most common SEPs to provide documentation.[6] In 2017, the Trump Administration began to require people enrolling through an SEP in the marketplace to submit documentation before they were granted coverage, which likely contributed to further declines in SEP take-up.

In addition to people who are eligible for SEPs but are deterred from enrolling by paperwork barriers, some would-be marketplace enrollees likely miss the annual open enrollment period, not because they’re purposely waiting to get sick before they buy coverage, but because they are unaware that there is a window of time each year when most people have to sign up for a marketplace plan.[7] Many people, regardless of income, experience challenges enrolling in health coverage because they lack needed information, are confused about what to do, or miss deadlines. And the marketplace enrollment schedule — with a short annual open enrollment period and (in most states) a cumbersome SEP process — leaves little room for such issues. (The Trump Administration exacerbated this problem when it cut the annual open enrollment period in half, to about six weeks, beginning with the 2018 plan year.)

Low-income people may be at particular risk of missing open enrollment deadlines. Research has shown that living in “chronic scarcity” (in which people lack money, time, and other basic resources) requires expending enormous mental effort to solve immediate problems, and that this makes decision-making more difficult and leaves less bandwidth to, for example, remember small details and remember to act.[8] Moreover, in Medicaid, low-income people can enroll in health coverage at any point during the year. And low-income marketplace enrollees have incomes that overlap with or are only a little higher than the incomes of people receiving Medicaid, which means that some may be more familiar with a continuous enrollment cycle. The marketplace open enrollment period also coincides with a period of the year when research shows lower-income households experience especially high levels of financial stress.[9]

The Massachusetts approach helps with these challenges, by allowing people with modest incomes to enroll in coverage even if they fail to apply during open enrollment.[10]

The Massachusetts policy is a legacy of the state’s pre-ACA health reform law, which initially allowed individuals to purchase coverage at any time during the year. The state later added an annual open enrollment period, after the conclusion of which enrollment became more restricted, but maintained the opportunity to enroll for those with incomes below 300 percent of the poverty line.

The concern about adopting this policy nationwide is that it could result in severe adverse selection, with people waiting until they get sick to enroll in a plan. But available data suggest that, if anything, Massachusetts has an unusually strong risk pool compared to other states, even with its relatively simplified path to enrollment throughout the year. Massachusetts’ marketplace premiums are among the lowest in the nation for 2019.[11] In addition, Massachusetts’ marketplace premiums (as of 2017) were 40 percent below the premiums for employer-sponsored insurance, according to an Urban Institute study, making them the lowest compared to employer premiums in any state.[12] (Employer-sponsored plan premiums are a good marker of what it costs to cover a well-balanced risk pool in a given location.)

While multiple factors likely contribute to Massachusetts’ strong market and limited adverse selection, these datapoints suggest that Massachusetts’ more open enrollment policies have not significantly undermined its risk pool, even as they appear to have significantly increased coverage in the latter half of the year.

The Senate bill would allow people who are determined eligible for federal premium tax credits and have incomes no greater than 300 percent of the poverty level to enroll at any time during the year, through a dedicated SEP. The Senate bill does not restrict eligibility to people who are new to the marketplace, in contrast to the Massachusetts policy.

Increased access to enrollment for lower-income people is just one provision of the broader Senate bill. Other proposals included in the Consumer Health Insurance Protection Act are likely to improve people’s ability to afford and access health coverage and medical services. For example, the bill would cap people’s out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs; apply the ACA’s pre-existing condition protections to short-term health plans; and allow more families that are offered employer-sponsored health coverage to qualify for marketplace subsidies if the employer plan isn’t affordable to the entire family.

Perhaps most significant, the Consumer Health Insurance Protection Act would also substantially increase subsidies, resulting in net premiums closer to Massachusetts levels. For example, an individual with income below 150 percent of the poverty line (about $18,000 per year for an individual) would be able to enroll in a benchmark marketplace plan for no more than about $30 per month, while people at 250 percent of poverty (about $30,000 per year for an individual) could buy benchmark coverage for no more than about $150 per month. The Senate bill also proposes greatly reducing the deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs that both low- and moderate-income people would pay with marketplace plans. The legislation also allows people with incomes greater than 400 percent of the poverty line to receive subsidies if premiums exceed 8.5 percent of their income; this group is ineligible for subsidies today.

It is likely that part of the reason Massachusetts has been able to maintain a more open enrollment system without serious adverse selection is that it provides additional subsidies to people with incomes up to 300 percent of the poverty level, on top of those available nationwide under the ACA. With lower net premiums ($0 or near-zero for many consumers), healthy people have no reason to wait until they get sick to enroll, so adverse selection is less of a concern. People who seek enrollment outside of the annual open period are likely mostly those who lost other coverage during the year (but who might not jump through extra hoops to prove eligibility for a Special Enrollment Period) or who missed, but didn’t deliberately sit out, the prior open enrollment period.

As in Massachusetts, improving marketplace subsidies would complement the Senate bill’s proposal for a simplified enrollment policy for lower-income consumers, boosting enrollment and helping to alleviate concerns about adverse selection.