Twenty-seven percent more people used special enrollment periods (SEPs) to sign up for plans in the federal marketplace in early 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.[1] While this is significant, far more people with health and financial worries during the COVID-19 pandemic likely would enroll in federal marketplace plans if given the chance.

With typical SEPs mainly available to those losing other health coverage, many people losing their jobs or much of their income in this crisis won’t qualify this year for marketplace coverage unless the Trump Administration provides an emergency SEP. Many people who are otherwise eligible for significant financial assistance in the federal marketplace (HealthCare.gov) will not be able to access it because they cannot enroll in a marketplace plan. Congress should direct the Administration to make marketplace coverage broadly available by creating an emergency SEP, especially given widespread support for the idea from patient groups, health care providers, state officials, employers, and the health insurance industry.

Many states that established emergency SEPs in their own state-run marketplaces have seen SEP growth far surpassing that of HealthCare.gov, even though smaller shares of the people losing their jobs in these states qualify for financial assistance to help pay for coverage. (Instead, more qualify for Medicaid or other health programs.) SEP growth in these state-run marketplaces is a sign that an emergency SEP could help expand enrollment in HealthCare.gov states as well.

SEPs allow people to sign up for marketplace plans outside the yearly open enrollment period that occurs each fall. The last open enrollment, for 2020 plans, had already ended when the pandemic and job losses hit the United States.

Typically, SEPs are only available to people who experience certain life events, such as losing other coverage, having a baby, or moving to a new geographic area. The COVID-19 crisis has harmed some people who, under current federal rules, are not eligible for a marketplace SEP — even if their income drops and they newly meet income criteria for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions available with marketplace plans. People who lose their jobs or experience a sharp drop in income but were already uninsured will not qualify to enroll through HealthCare.gov. (An SEP is already available in all states to people who lose health coverage through a job, but not to people who lost a job but not health coverage.) Among people who have lost their jobs in this economic crisis, most did not previously have coverage through their job, a Commonwealth Fund survey found.[2]

And even for people who qualify for an SEP, following through to enrollment can be challenging. First, they must know where and how to apply for coverage, but many people are not familiar with the marketplaces or the situations that trigger an SEP. Second, they usually have a 60-day deadline, so they lose their opportunity if they delay enrolling in the months after they lose their job-based health coverage. Third, to apply, people must supply all the usual information needed for an eligibility determination as well as details related to SEPs, such as when they lost other coverage. Often, they must supply documents (such as a letter from a former employer or health insurer) to verify that they are eligible for an SEP, creating an additional barrier. Earlier this year, in response to the COVID-19 emergency, HealthCare.gov was allowing people to attest to their eligibility rather than requiring paper documents to prove SEP eligibility, but it has now reportedly resumed requiring documentation from many people applying for SEPs.[3]

Most states that fully run their own health insurance marketplaces (rather than relying on HealthCare.gov) quickly implemented time-limited emergency SEPs in response to the public health crisis. (This includes 11 states and Washington, D.C. — all state-based marketplaces except Idaho.)

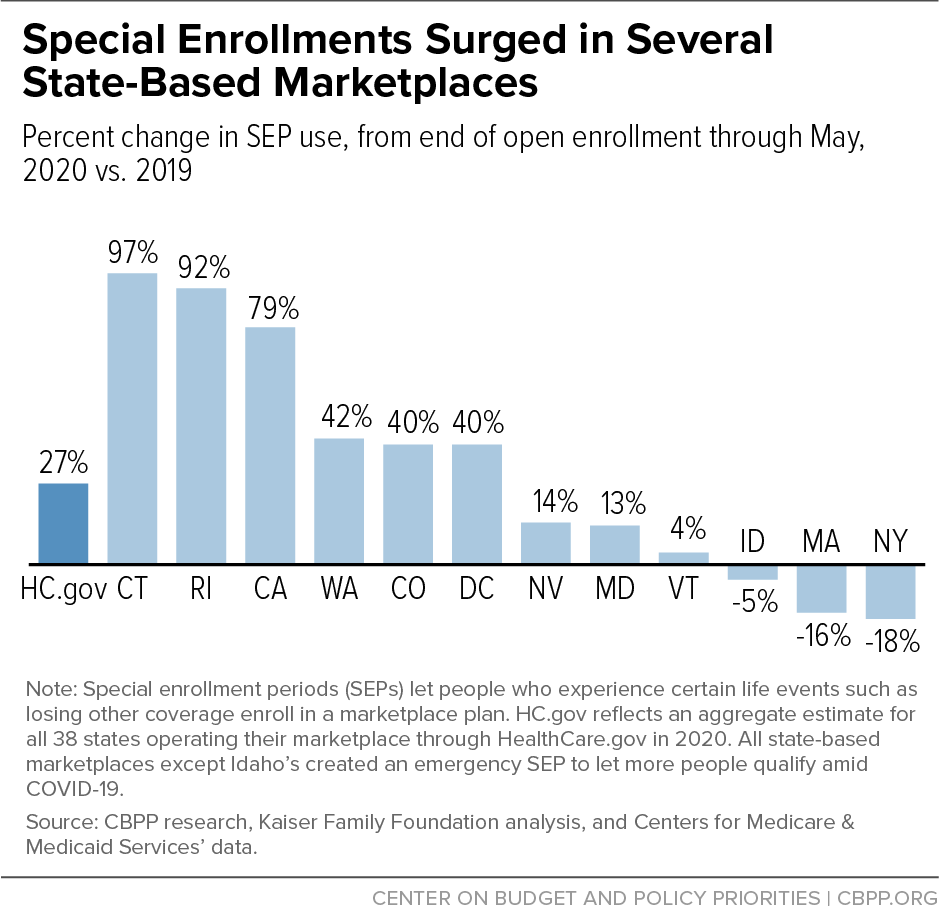

Figure 1 compares SEP enrollments in 2020 (from the end of open enrollment through May) to 2019 SEP enrollments during similar periods, in most states that operate their own marketplaces and across states that use HealthCare.gov. Six of the states (including D.C.) that operate their own marketplaces and created emergency SEPs saw enrollment surge far beyond the federal marketplace’s 27 percent increase. (For two of states that run their own marketplaces, data are unavailable.) In Connecticut, SEP enrollments increased 97 percent in the first five months of 2020 compared to 2019. In Rhode Island they increased 92 percent, and in California 79 percent. (See Figure 1 and Appendix 1.)

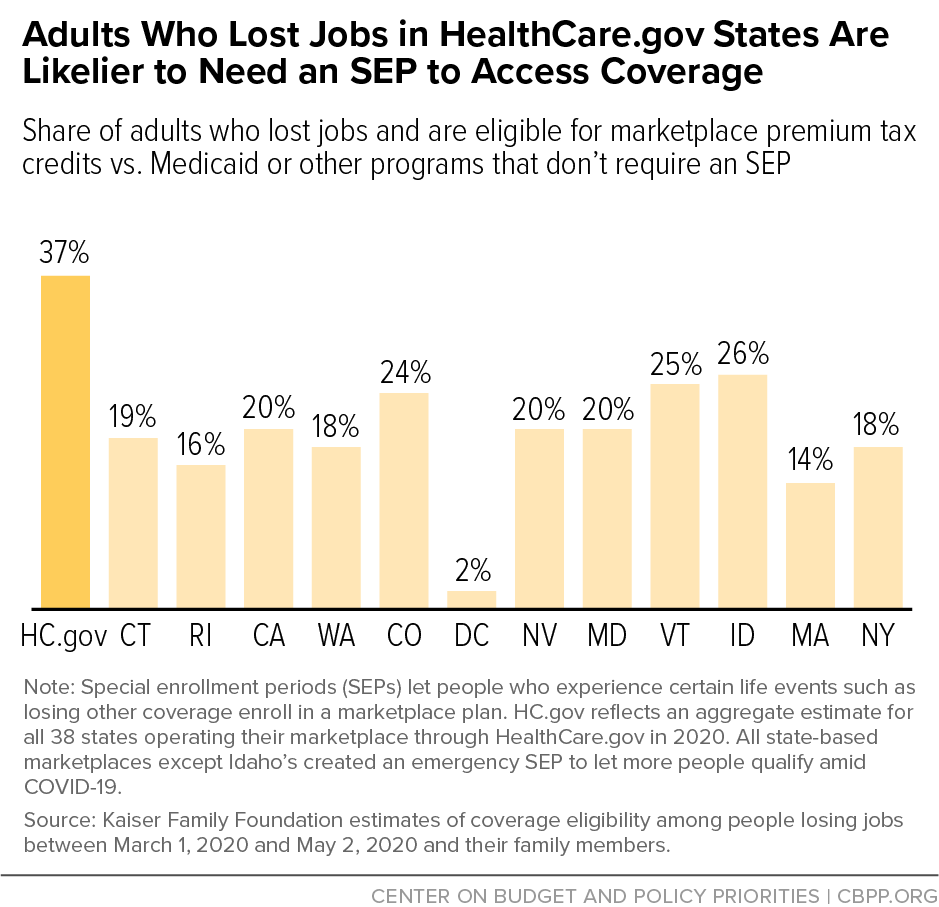

These increases are especially striking because, all else equal, these states would have been expected to see much smaller increases in SEP enrollments than the HealthCare.gov states. Unemployment rates were similar on average across these states and the HealthCare.gov states. Meanwhile, a smaller fraction of uninsured people and/or newly unemployed people in these higher-enrollment states are eligible for marketplace coverage.

That’s primarily because all of these states adopted the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults. In Medicaid expansion states, most people with incomes between 100 to 138 percent of the poverty line are eligible for Medicaid, whereas they are eligible for marketplace coverage and financial assistance in non-expansion states. Across all HealthCare.gov states, including the 15 states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion, about 37 percent of the people losing their jobs are eligible for marketplace coverage with premium tax credits, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates. By comparison, about 19 percent of the people losing jobs in all states that run their own marketplaces are eligible for premium tax credits. (See Figure 2.) People can enroll in Medicaid at any time during the year and do not need an SEP.[4] Many state-based marketplace officials report that, as a result of the economic crisis, many of the people who are seeking health coverage have incomes low enough to qualify for Medicaid, rather than marketplace financial assistance.

Of course, not all states that created emergency SEPs saw enrollment gains. And many factors influence SEP enrollment levels from year to year.

In Massachusetts and New York, which reported reductions in SEP enrollment compared to last year, fewer transitions into the marketplaces from Medicaid are one likely reason. Federal COVID-19 legislation currently prevents anyone from losing Medicaid eligibility, minimizing this category of SEP enrollments into marketplaces while also helping protect people from becoming uninsured.[5] While this dynamic exists in every state, states with Medicaid expansion and highly integrated eligibility systems, such as Massachusetts and New York, should see the biggest impact on their SEP totals. Normally, when people in these states lose Medicaid and become eligible for a marketplace plan, they are granted an SEP and transition promptly into the new coverage. Exchange officials in Massachusetts and New York said this type of SEP, normally a significant portion of SEP enrollment, is down compared to past years as people are remaining enrolled in Medicaid instead. (In Massachusetts, people transitioning from Medicaid normally account for about a third of monthly SEP enrollments.)

Meanwhile Idaho — the only state with its own marketplace that did not create an emergency COVID-19 SEP — saw SEP enrollments drop, a major reason for which is that the state implemented Medicaid expansion beginning January 1, 2020. That significantly reduced the number of people eligible for marketplace coverage compared to the previous year.

And in states where SEP enrollments did rise substantially, the emergency SEP was not the only factor. For example, California’s new health insurance mandate and supplemental state subsidies likely boosted its SEP enrollments. Such enrollments were higher in 2020 than in 2019 even before the start of the pandemic, but the increase was much greater after the state created its COVID-19 SEP. California also conducted significant outreach to inform the public about the emergency SEP, as did Nevada and several other states.[6]

Nonetheless, the data from state-based marketplaces reinforce a commonsense conclusion: giving people more opportunities to enroll in coverage and making it easier for them to do so leads to more people getting health insurance.

The House included a new marketplace SEP, which would last for eight weeks, as part of the Heroes Act, the COVID-19 relief package it passed in May. Legislation is needed because the Trump Administration rejected using its administrative authority to set up a new SEP in federal marketplace states, despite broad support for the idea. In the next COVID-19 relief package, Congress should ensure that more people enroll in comprehensive health coverage this year by establishing a new SEP for people living in federal marketplace states.

The federal government, as part of a data release on special enrollments, reported that from the end of the open enrollment period through May, SEP sign-ups increased 27 percent in the 38 states that use HealthCare.gov. To compare this to SEP sign-ups in state-based marketplaces, we obtained similar data from ten states and D.C. through publicly available reports and/or by contacting the state-based marketplaces. There are, however, differences in how states collect and report the data that could affect the accuracy of the comparisons. Below are notes on the data and sources:

- Time periods differ for SEP data from different states. For HealthCare.gov states and some state-run marketplaces where open enrollment ended in December, SEP data begin in December or January. Other states with their own exchanges had longer open enrollment periods, so their SEP growth was calculated for a shorter period of time, beginning after the open enrollment period ended.

- States differ in how they report their enrollment data, with some reporting plan selections and others reporting effectuated enrollments.

- California’s publicly available data run through May 16, rather than through the end of that month.[7]

- Colorado’s data were obtained from the state exchange and run from mid-January through May.

- Connecticut’s data were obtained from the state exchange and run from mid-December through May.

- Washington, D.C.’s data were obtained from the state exchange and run from mid-February through May.

- Idaho’s data were obtained from the state exchange and run from January through May.

- Maryland’s data were obtained from the state exchange and publicly available reports and run from January through May.[8]

- Massachusetts’ publicly available data cover the period from February through May.[9]

- Minnesota’s exchange reported 20,500 plan signups from January through May 2020 but comparable data for 2019 were not available as of publication.

- Nevada’s publicly available data cover the period from mid-December through May.[10]

- New York’s data were obtained from the state exchange and run from February through May.

- Rhode Island’s data were obtained from the state exchange and run from February through May.

- Vermont’s data were obtained from the state exchange, run from February through May, and represent households rather than individuals.

- Washington State’s data were obtained from exchange staff and publicly available reports and run from January through May.[11]

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| State |

2019 SEP enrollment |

2020 SEP enrollment |

% change, SEP enrollment |

|---|

| California |

107,170 |

191,380 |

79% |

| Colorado |

28,161 |

39,332 |

40% |

| Connecticut |

3,491 |

6,868 |

97% |

| D.C. |

2,015 |

2,828 |

40% |

| Idaho |

8,907 |

8,458 |

-5% |

| Maryland |

39,012 |

44,007 |

13% |

| Massachusetts |

70,737 |

59,264 |

-16% |

| Nevada |

6,600 |

7,556 |

14% |

| New York |

40,000 |

33,000 |

-18% |

| Rhode Island |

2,466 |

4,725 |

92% |

| Vermont |

1,679 |

1,749 |

4% |

| Washington State |

29,052 |

41,242 |

42% |

| Federal marketplace states |

704,106 |

892,141 |

27% |