BEYOND THE NUMBERS

People who seek Social Security disability benefits face many financial, social, and health challenges, a recent study confirms, rebutting any notion that applicants who are denied benefits can shrug it off and return to work. As we mark the 64th birthday of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) this month, let’s remember not just how much hardship it alleviates but the continued struggles of people who fall short of its stringent eligibility standards.

The study’s author, longtime Social Security Administration and Congressional Budget Office researcher David Weaver, analyzes people who have ever received SSDI or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits and those who’ve been rejected for them.

Compared with people who never sought benefits, Weaver finds, beneficiaries and rejected applicants alike are:

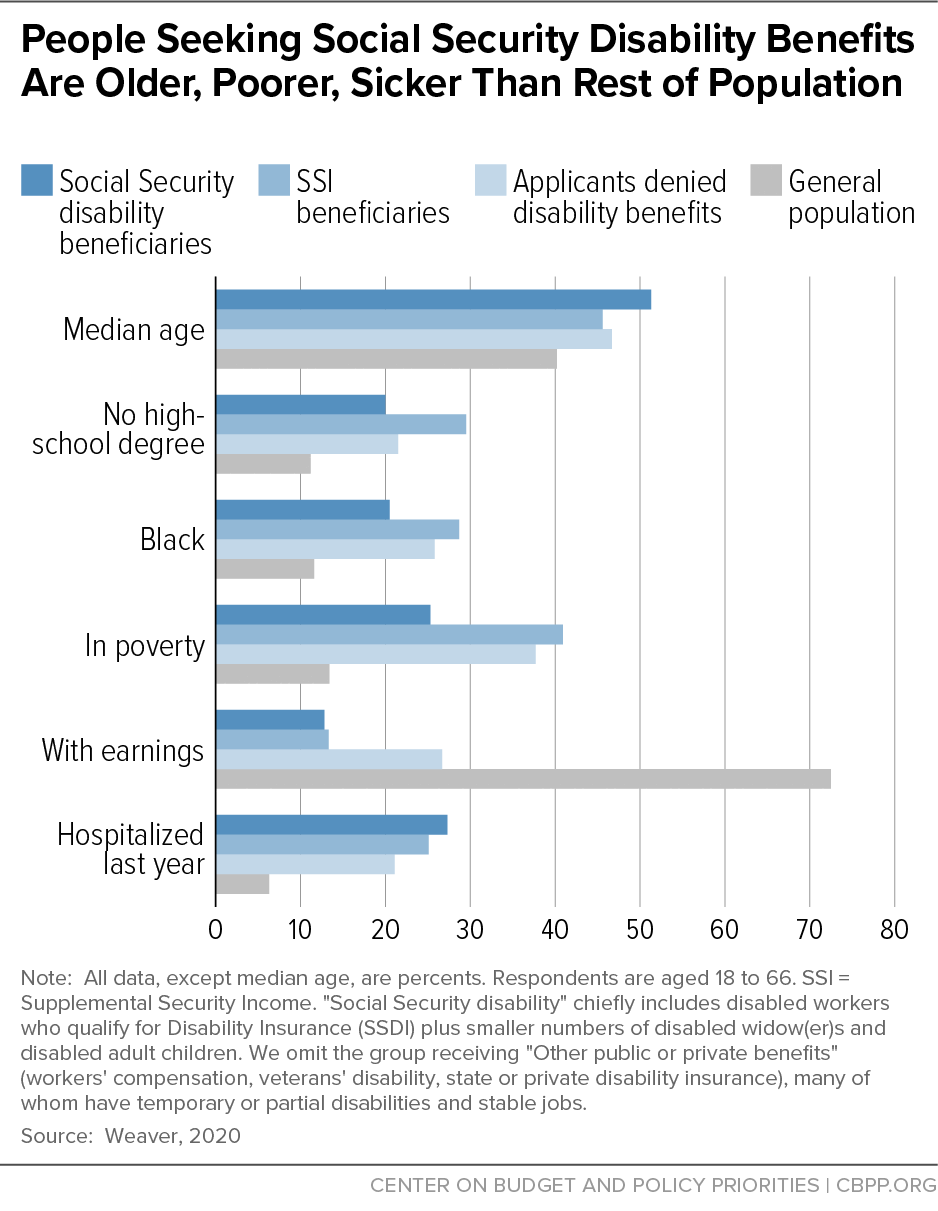

- Older. SSDI’s typical beneficiary was 51, about 5 years older than the typical SSI recipient and denied applicant, and 11 years older than other working-age people. (See graph). That’s no surprise: disability rates rise steeply with age.

- Less educated. People with Social Security disability “exposure” — our catchall term for awarded and rejected applicants and SSI recipients — are about twice as likely to lack a high-school diploma as other people. Often, a disability prevents them from doing their old job and they lack the education, skills, and experience to switch to another one late in their career.

- Likelier to be Black. People with disability program exposure are roughly twice as likely to be Black as non-exposed people. Persistent racial disparities in health care access and quality — as well as in access to nutritious food, well-funded schools, and economic opportunity — mean that African Americans are likelier to have poor health and low-paid, physically taxing jobs, all of which are associated with disability or premature death.

- Likelier to live in the South. Disability recipients and applicants live everywhere, but they’re especially clustered in the Deep South, Appalachia, and around the Great Lakes. States with high rates of disability receipt tend to have populations that are less educated, older, and more blue collar than other states, and to have fewer immigrants.

- Poorer. Poverty rates are 2 to 3 times higher among people who seek disability benefits. So is “material hardship,” a measure that combines food insecurity and trouble paying rent or utilities.

- Less likely to be working. Few denied applicants, and even fewer beneficiaries, work. And if they do, their earnings are much lower than other people’s.

- Sicker. People with disability program exposure are 3 to 4 times likelier to have been hospitalized, and to have frequent doctor visits, than other people. They report less physical stamina and more mental troubles like depression, anxiety, and poor concentration.

These findings echo past studies that tracked denied applicants and found limited employment and severe financial strain. As Weaver observes, little help — except a patchwork of social services, family aid, and vocational rehabilitation — is available to these unlucky people. Some might qualify for Social Security disability later as they grow older and their health worsens. Or they might have to hang on until they can receive early Social Security retirement benefits at 62.