- Home

- Social Security

- Supplemental Security Income

Policy Basics: Supplemental Security Income

Created in 1972, the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program provides monthly cash assistance to disabled or older people who have little income and few assets. Like the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, commonly known as Social Security, SSI is administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA). In January 2024, 7.4 million people collected SSI benefits.

Who Qualifies for SSI and What Benefits Do They Receive?

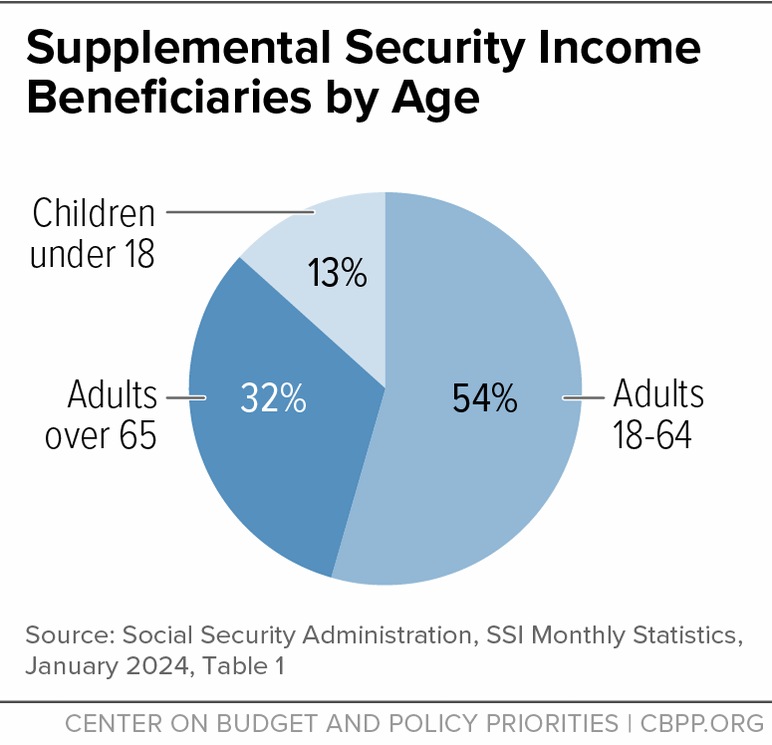

The vast majority of SSI beneficiaries — 84 percent — are eligible due to a severe disability (including blindness). In January 2024, roughly 1 million beneficiaries were children. Since SSI is available only to those who are disabled or over age 65 and have very low incomes and assets, more disabled children become eligible for SSI when poverty rates rise.

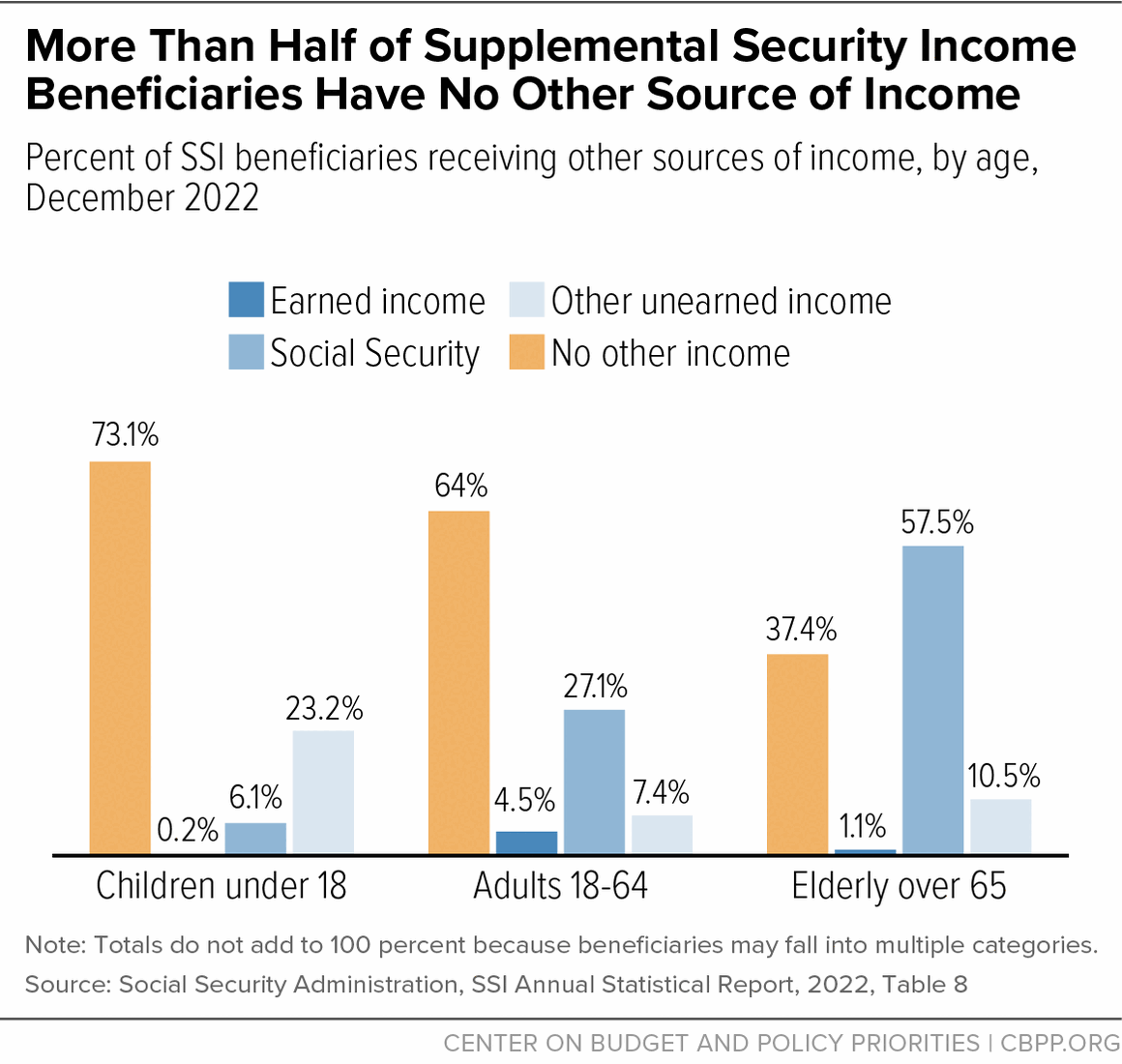

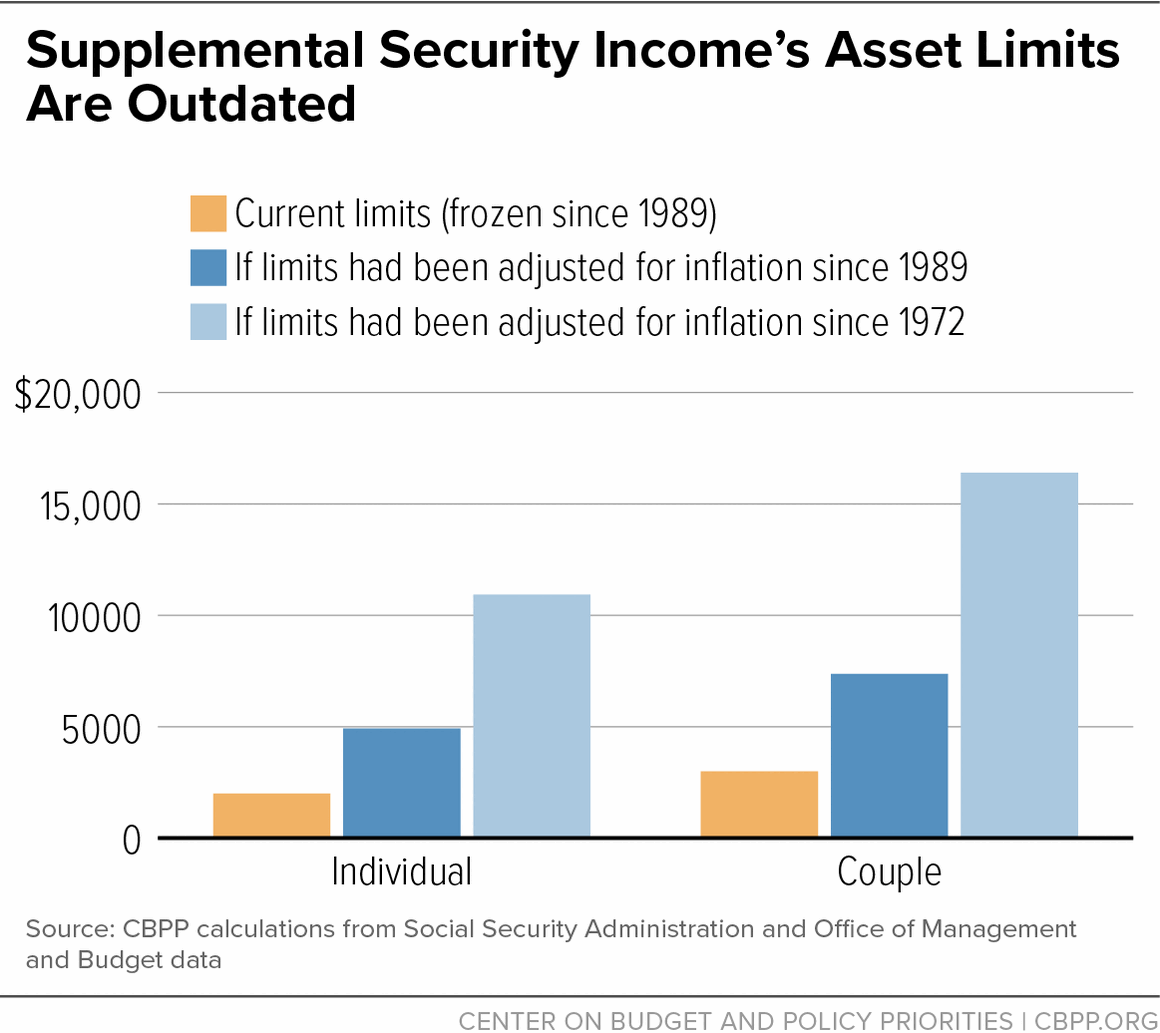

SSI beneficiaries may have no more than $2,000 in assets for individuals and $3,000 for couples, with certain exceptions. Because beneficiaries typically have no other source of income, more than half receive the basic monthly SSI benefit, which in 2024 is $943 for an individual and $1,415 for a couple.

SSA reduces these benefit amounts for beneficiaries who have other sources of income or who live in a Medicaid facility or with someone who provides support. For example, while SSA exempts (or “disregards”) the first $20 per month of unearned income when determining a person’s SSI eligibility and benefit levels, any income above that amount from sources such as Social Security benefits, pensions, interest, and child support is subtracted from SSI benefits. Similarly, SSA disregards the first $65 per month of earnings, but each dollar of earnings above that level typically reduces SSI benefits by 50 cents. Such reductions lowered the average SSI monthly benefit to $698 in January 2024.

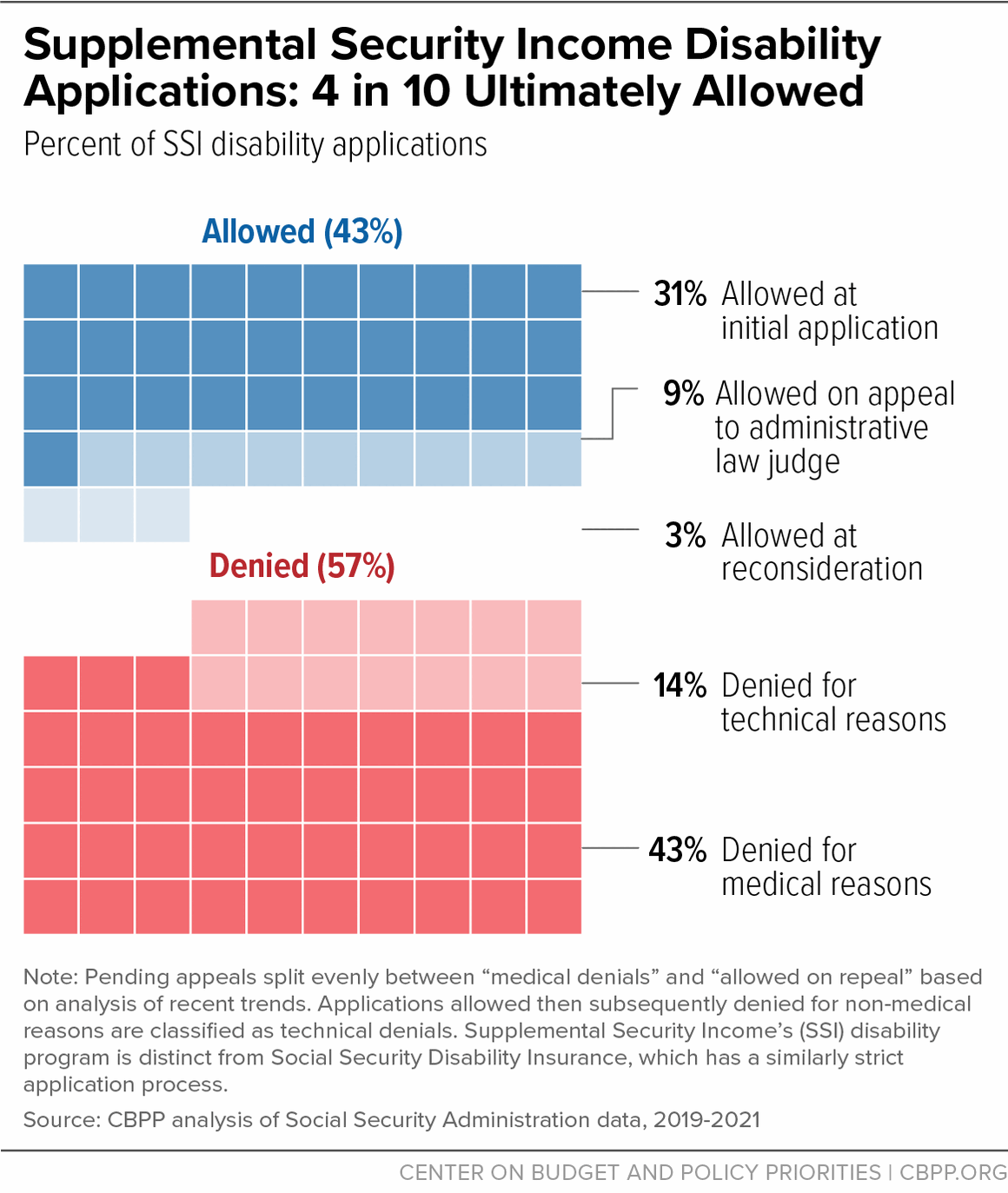

Eligibility criteria for SSI are strict. All applicants must meet SSI’s stringent financial criteria, and applicants for disability benefits must also meet the same rigorous medical criteria used for Social Security Disability Insurance. Most applications for SSI disability benefits are rejected. SSA denies applicants who are technically disqualified (mainly because they have income or assets above the limits for eligibility) and sends the rest to state disability determination services for medical evaluation. About 4 in 10 applicants were found eligible for SSI between 2019 and 2021.

Among the U.S. Territories, only residents of the Northern Mariana Islands receive SSI benefits. Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands receive a federal block grant called Aid to the Aged, Blind, and Disabled (AABD), which provides far lower benefits and has stricter eligibility criteria. American Samoa has neither SSI nor AABD.

In most states, SSI beneficiaries are automatically eligible for Medicaid, which provides essential long-term services and supports. Medicaid supports home- and community-based services, such as personal and attendant care services that help people with disabilities live in their homes and communities. Medicaid also covers wheelchairs, lifts, and supportive housing services. This care is typically unavailable through private insurance and is too costly for all but the wealthiest people to fund out of pocket. In 2016, 52 percent of SSI beneficiaries also received Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program assistance (formerly food stamps), and roughly one-quarter received housing assistance. Finally, many states supplement the federal SSI benefit, though some have cut those additional payments over the years.

How Has SSI Changed Over Time?

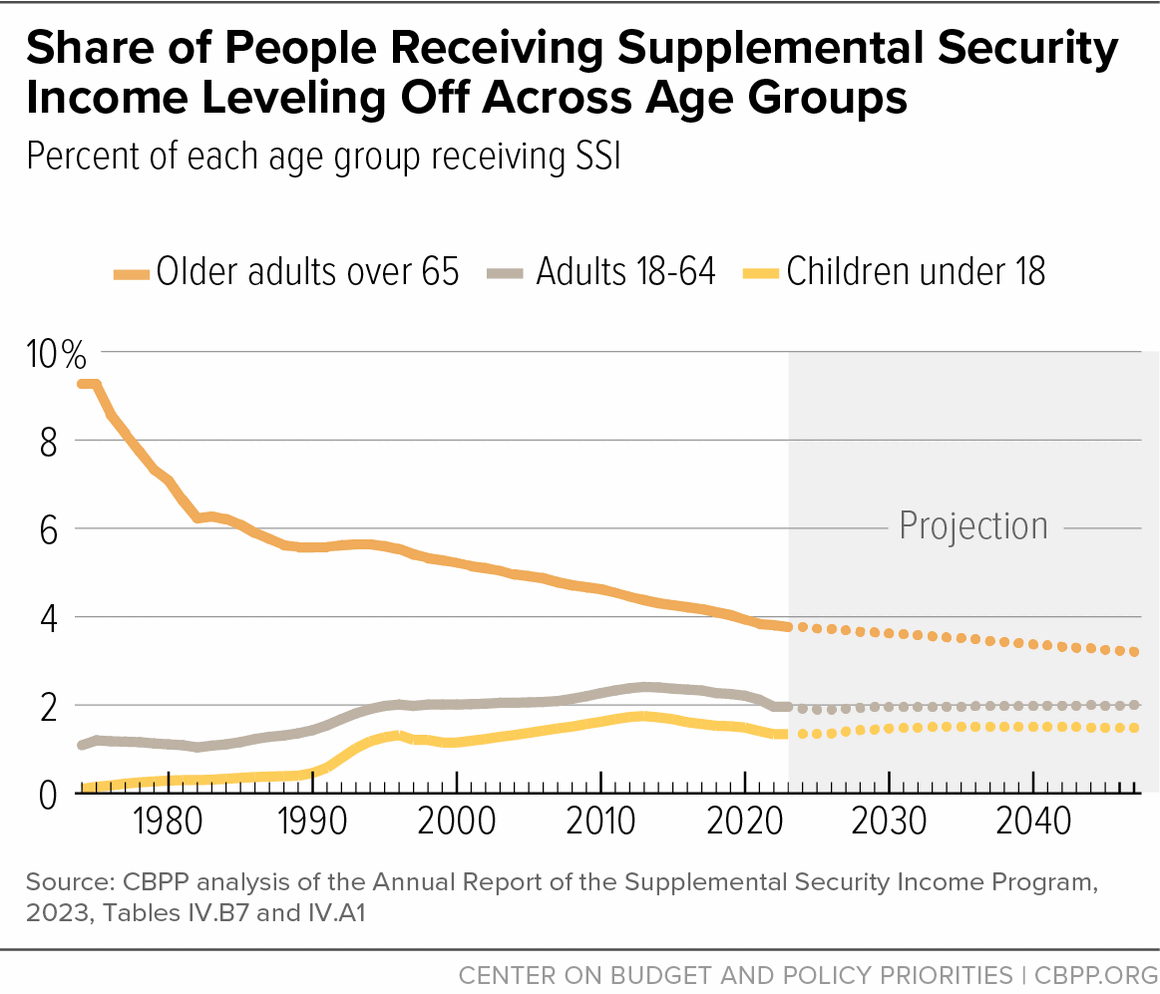

Since SSI benefits were first distributed in 1974, the share of older people receiving benefits has fallen steadily, mostly because fewer people in this group qualify under SSI’s increasingly stringent income limits. The share of children and adults with disabilities receiving SSI has grown, partly due to policy changes in 1984 that expanded eligibility based on mental health conditions and a 1990 Supreme Court ruling that expanded the SSI disability criteria for children. A statutory change in 1996 restricted eligibility for children and immigrants. The share of people in the U.S. receiving SSI has fallen in recent years and is projected to remain steady at around 2.15 percent in the long term. The share of people from specific age groups receiving SSI is expected to stay steady or (in the case of older people) to continue declining.

How Is SSI Funded?

Unlike Social Security, which is financed by dedicated payroll taxes, SSI is funded from general revenues. SSI expenditures, at $65 billion in fiscal year 2022, were 0.26 percent of gross domestic product that year. More than $9 of every $10 pays for benefits; the rest covers administrative costs. SSI’s administrative costs are substantially higher than those for Social Security because of its complex rules.

How Effective Is SSI?

Before any state supplement, and without income deductions, SSI benefits are about three-fourths of the poverty line for a single person. Thus, while SSI alone is not enough to lift someone living independently above the poverty line, it reduces hardship and lessens the need for support from family members. But in 2016, roughly half of all beneficiaries had incomes below the federal poverty line even with their SSI benefits.

Many other older adults or disabled people in need, including people with a lawful immigration status affected by the 1996 eligibility restrictions, don’t get benefits.

Ways to Improve SSI

Congress can strengthen SSI by updating the asset limits and income disregards and indexing them to inflation. The asset limits have been frozen since 1989, and the income disregards have remained the same since SSI’s launch in 1974, preventing many older adults and disabled people in need from qualifying.

Congress can also improve SSI by increasing the basic SSI benefit, partially exempting retirement savings from the asset limits, and easing eligibility restrictions for people with a lawful immigration status.