- Home

- Retirement Security

- Social Security Disability Insurance

Policy Basics: Social Security Disability Insurance

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) provides earned benefits for workers who can no longer support themselves through work due to severe impairments.

Disability Insurance: A Crucial Part of Social Security

SSDI is an integral part of Social Security. Workers contribute to SSDI and earn its protection in case they can no longer support themselves through work due to a severe and long-lasting disability. The Social Security Administration (SSA) administers SSDI.

In January 2023, 7.6 million people received disabled-worker benefits from Social Security. Payments also went to some of their family members: 90,000 spouses and 1.1 million children.

SSDI benefits are financed primarily by Social Security payroll tax contributions and totaled about $141 billion in 2021. That’s only about 2 percent of the federal budget and less than 1 percent of gross domestic product. SSDI’s share of the payroll tax is now 0.9 percent of earnings up to Social Security’s taxable maximum, currently $160,200. Benefits are paid from the SSDI trust fund, which is legally separate from the much larger retirement and survivors trust fund. The most recent projections estimate that the SSDI trust fund will be fully funded throughout the 75-year projection period, which currently runs to 2096.

Workers Earn SSDI Benefits Through Work

SSDI protects over 159 million workers. To become eligible for benefits, beneficiaries must meet stringent criteria:

- Insured status. Beneficiaries must be both “fully insured,” meaning they have worked for at least one-fourth of their adult lives, and “disability insured,” meaning they have worked in at least five of the last ten years.

- Severe impairment. Beneficiaries must suffer from a severe, medically determinable physical or mental impairment that has lasted for five months and is expected to last at least 12 months or result in death.

- Inability to perform substantial work. Beneficiaries’ physical or mental impairments must render them unable to do their own past work and unable — considering age, education, and work experience — to do any other kind of substantial work. “Substantial work,” in 2023, means earnings of $1,470 a month ($2,460 for people who are blind), which is about 40 percent of the median earnings of a full-time worker with a high school diploma but no college.

The large majority of SSDI beneficiaries have extensive work histories; the average beneficiary had 22 years of work experience and earned middle-class wages before becoming disabled. A typical SSDI beneficiary is in late middle age — about 79 percent are 50 or older, and 44 percent are 60 or older — and suffers from a severe mental, musculoskeletal, or other debilitating impairment. Beneficiaries’ labor market prospects are very poor, and their death rates are at least three times as high as the general population’s.

SSDI’s strict criteria mean SSA rejects most applicants. The agency first screens for technical disqualifications (primarily, failure to meet SSDI’s work history requirements), then submits the remaining applications to each state’s disability determination services (DDS) for medical and vocational evaluation. If denied at the DDS level, an applicant may appeal. Ultimately, fewer than 1 in 3 applicants are awarded benefits. SSA regularly reviews beneficiaries to end SSDI payments to those who have recovered.

A Lifeline for Workers Facing Hardship

SSDI beneficiaries receive modest cash benefits, based on their average earnings over their career, after a five-month waiting period. The benefit formula is progressive: higher earners receive a benefit that is larger in dollar terms but represents a smaller fraction of their prior earnings. After 24 months of receiving benefits, SSDI beneficiaries also become eligible for Medicare.

The average monthly SSDI benefit for disabled workers in January 2023 was $1,483 (or roughly $17,800 annually). Benefits replace about half of disabled workers’ final earnings prior to disability, on average. In a minority of cases, other family members may also be eligible for benefits — most commonly, the minor children of the worker.

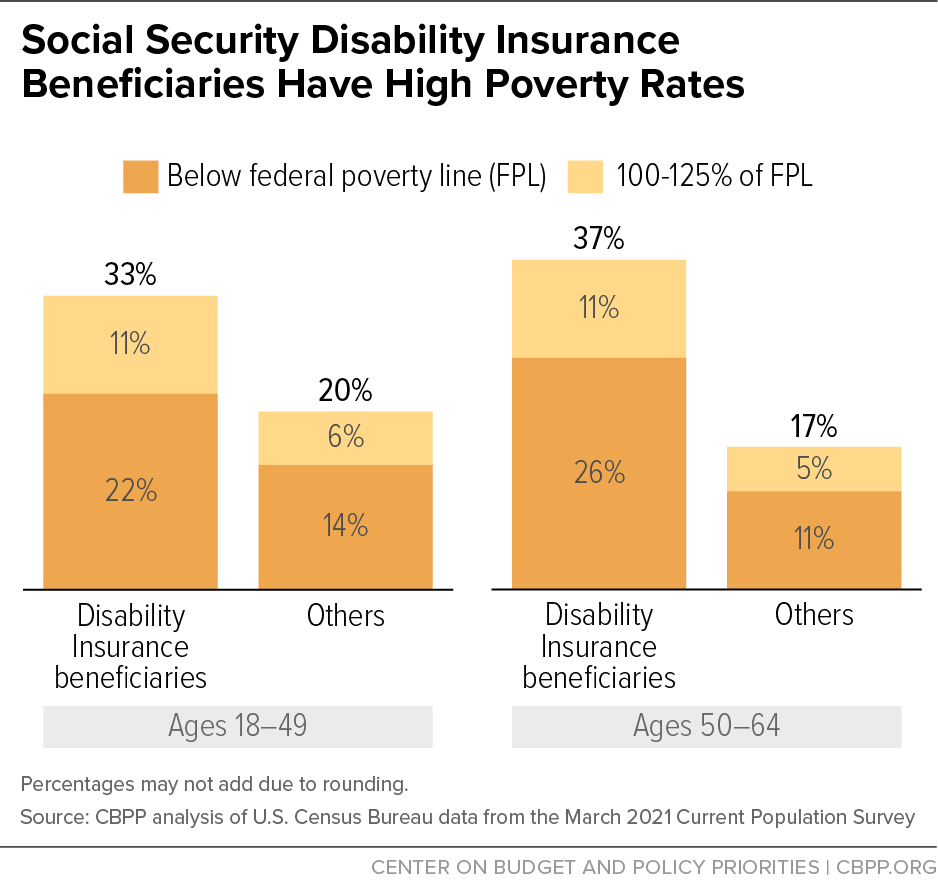

SSDI provides a lifeline for workers experiencing great hardship. Without it, nearly half of disabled workers would be experiencing poverty. Even with disability benefits, about 1 in 5 disabled workers are below the poverty line, and many are near the poverty line.

SSDI Contains Significant Work Incentives

All SSDI beneficiaries can earn up to $1,470 a month (in 2023) as long as they are able to work, with no loss in benefits — which could more than double the income of a beneficiary receiving the average benefit of $1,483. Beneficiaries may earn unlimited amounts without jeopardizing their benefits while they test their ability to return to work during a nine-month trial work period and three-month grace period. Other program features, like extended Medicare eligibility, are designed to smooth their transition back to the labor market. SSDI benefits are low, and one would expect beneficiaries to take advantage of these rules by trying to supplement their benefits with earnings if they are able to do so.

However, evidence suggests that few beneficiaries could earn more than very small amounts if they did not receive SSDI. Only a minority of beneficiaries ever work again after qualifying for the program. Most applicants’ earnings fall sharply before they turn to SSDI. Few beneficiaries are able to earn even close to the maximum allowed. Additionally, studies of rejected applicants show they struggle in the labor market — evidence that SSDI’s criteria for disability are, indeed, very strict.

Trends in SSDI Enrollment

The number of SSDI beneficiaries grew throughout most of the program’s history, mainly reflecting demographic factors: the population increased; baby boomers aged into late middle age, when the odds of becoming disabled rise sharply; and more women joined the workforce, paid into Social Security, and earned coverage.

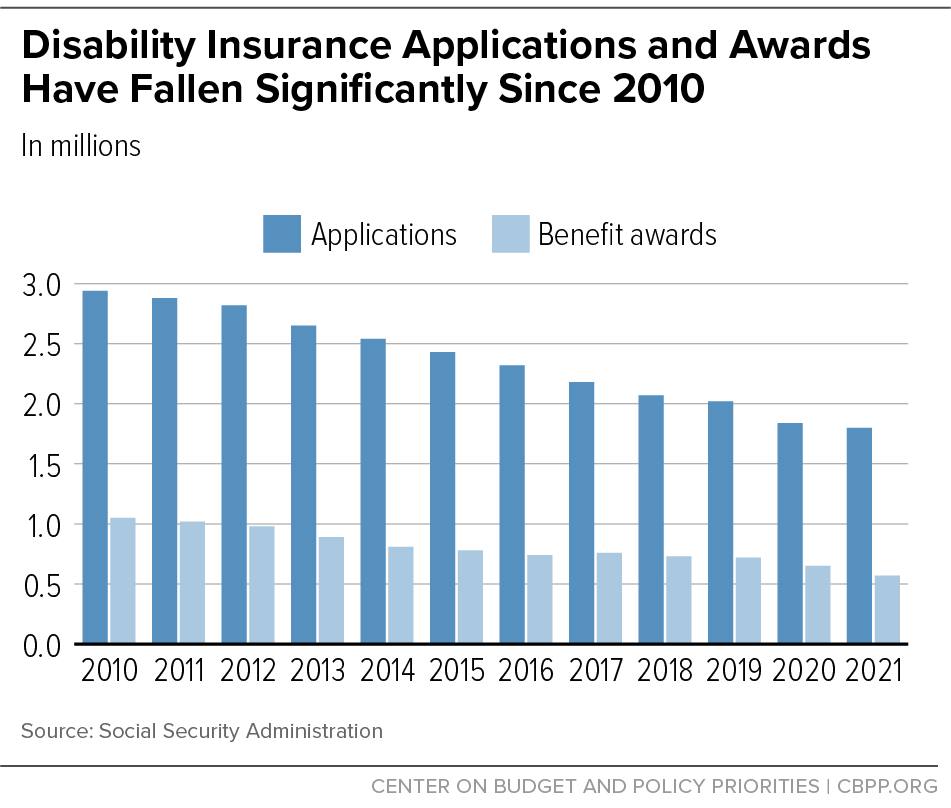

However, this trend has reversed in recent years as demographic factors have changed. SSDI applications and awards have fallen by roughly 40 percent since 2010, while the number of beneficiaries has dropped by around 2 million over the past ten years. Social Security’s trustees project that the share of people in the U.S. receiving SSDI will rise somewhat over the next 20 years and then remain stable.

Updated March 13, 2023

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.