Families’ access to wealth has played a large role in determining how the pandemic has affected them. The worst of the economic and health effects have largely bypassed wealthier, higher-paid families — which are disproportionately white — but have been far more prevalent among lower-income families and those of color. Amid sizeable state budget shortfalls and an unequal recovery that has exacerbated racial inequities, states would be well-advised to raise taxes on wealthy families to preserve funding for crucial priorities that can promote an equitable recovery — among them education, increased health spending to contain the pandemic, and boosts to cash assistance and other programs to help struggling families make ends meet during the crisis.[1]

Other approaches states could take to balance their operating budgets, as nearly all states must each year, risk worsening racial inequities, increasing hardship, and slowing the economic recovery.[2] When states cut funding for schools, health care, or other services, it typically results in layoffs, which reduce economic activity and can deepen and prolong a recession. Tax increases that ask more of low-income households as a share of their income can have a similar effect: many of these households are already spending far less due to job losses and the recession and would reduce their consumption further.

Wealthy households, meanwhile, typically have large amounts of disposable income and so do not alter their consumption much, if at all, when state taxes increase. Further, most state tax systems ask much less of very high-income households, as a share of income, than of those struggling to get by. States would do well to address this preferential tax treatment, including through steps to strengthen taxes on the following:

- High wage and salary income. Most states now have upside-down tax systems in which those who earn the least pay the most as a share of their income. Opting instead to raise personal income tax rates on the highest-income households, such as through a “millionaires’ tax” (i.e., a tax on people with annual incomes exceeding $1 million), is a sound way to tax high income and help form a more solid foundation for a state’s tax base.

- Real estate. “Mansion taxes” on high-value homes, or on their sale or purchase, are an attractive option for states looking to tax wealth, especially with the economic crisis having largely spared the high-value housing market.

- Income from capital gains, the income that an investor receives when a financial asset is sold for profit, is highly concentrated among the wealthiest households. The stock market’s strong performance despite the pandemic is preserving those profits for many wealthy families. Options to raise taxes on this income include eliminating tax breaks on it and raising the rates it is subject to, either permanently or as a pandemic surcharge.

- Inherited wealth. We recommend that states that have no estate or inheritance tax on wealthy individuals implement such a tax, and that states that already have such taxes consider raising their tax rates or lowering the threshold at which the tax begins to apply. Current state thresholds range as high as $5.6 million, which can leave untaxed all but the wealthiest estates and thereby worsen inequality.

COVID-19’s effects have been widespread but unequally felt. By and large, economically struggling families and many communities of color have suffered worse economic and health outcomes, while wealthier families, which are disproportionately white, have fared better.

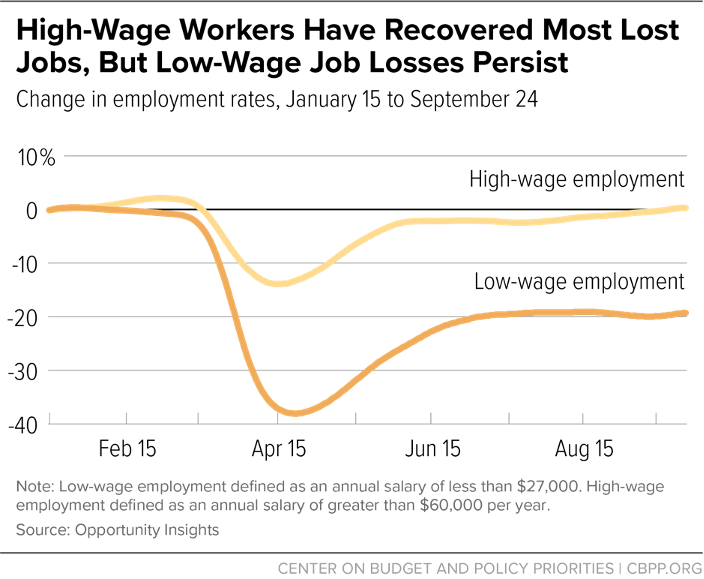

High earners have been much less likely to lose jobs than other workers due to COVID-19. For people earning over $60,000, the employment rate is close to its pre-pandemic level. But for workers earning less than $27,000, the employment rate is more than 19 percent below its pre-pandemic level, according to Opportunity Insights.[3] (See Figure 1.)

The stock market and luxury homes have also fared relatively well during the pandemic. This, coming alongside low-wage job losses, has exacerbated already high disparities in wealth holding.[4] The stock market has exceeded its pre-pandemic peak, which mainly helps more affluent families. Over 90 percent of capital gains go to families earning over $163,000 a year, and stock market investment rises steeply with income.[5] Luxury home values in many areas across the country have actually risen since the beginning of the pandemic, increasing 6.5 percent compared to the same point last year. And sales of luxury homes increased 42 percent during that same period, boosting the wealth of homeowners who made these sales, a group that tends to be both more affluent than the overall population and disproportionately white. Meanwhile, sales of affordable homes have declined more than 4 percent.[6]

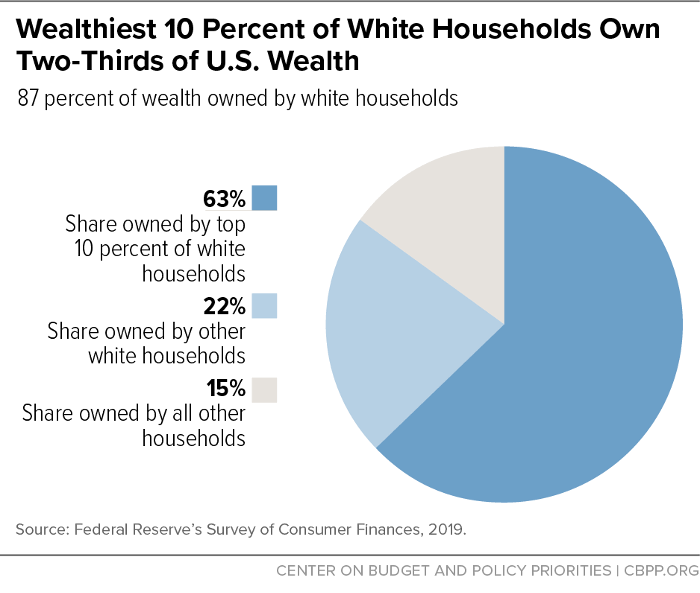

COVID-19 and its economic fallout have hit Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and many immigrant people particularly hard. The disproportionate impacts reflect harsh, longstanding inequities — often stemming from structural racism — in education, employment, housing, and health care that the current crisis is aggravating.[7] Before the pandemic, the wealthiest 10 percent of white households owned 65 percent of U.S. wealth. (See Figure 2.) That figure may be even higher now because of the effects of the pandemic on lower-income households, with people of color, particularly women, being overrepresented in low-wage jobs and therefore likelier to have lost jobs and income due to the pandemic. Furthermore, 1 in 5 renters is now behind on rent, with Black and Latinx renters facing the highest rates of such hardship.[8]

Taxes on High Incomes and Wealth Would Raise Badly Needed State Revenue

The economic downturn caused by COVID-19 has caused states revenues to drop markedly.[9] The resulting budget shortfalls are large, likely about 10 percent of states’ budgets over the next two years, and could grow higher if the current surge in COVID cases grows further or continues for a number of months.[10] The shortfalls affect nearly every state and are already driving painful cuts to services and large-scale layoffs and furloughs of state and local workers. That means fewer school workers and, in the middle of a pandemic, cuts to health care. Beyond increasing hardship at a time when 1 in 3 adults has trouble paying usual household expenses, such cuts could deepen and prolong the recession and worsen racial inequities.[11]

At this point in the pandemic, many states are responding to revenue shortfalls by operating under temporary budgets in the hopes that additional federal aid will arrive, and by proposing steep budget cuts. Some governors have called for across-the-board cuts in all areas of government. Some states have already directly cut pandemic response services and health department budgets or positions.[12] In addition, states and localities have laid off or furloughed over 1 million workers — far more than such losses due to the Great Recession — over three-fourths of whom work in K-12 or higher education. Most states will try to shield K-12 public schools and health services from further damage, but because education and health make up more than half of state spending nationwide, they may not be able to.

Even if states receive urgently needed federal aid, they should improve their taxation of wealth and high incomes to put families and communities first and contribute to an equitable, antiracist response to the pandemic.[13] These taxes are based on individuals’ ability to pay, which is especially important given the unequal recovery. Rather than pitting various needs against each other in a debate over which services to cut, raising taxes on high incomes and wealth can allow lawmakers to support communities — particularly communities of color — hit particularly hard by the pandemic, by using revenue that comes heavily from those doing very well despite the current challenges.

Taxes on high incomes and wealth can begin to lessen racialized wealth and income inequality, which the pandemic is worsening. In addition to their greater likelihood of job and income losses, people of color are experiencing disproportionately more COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations — and Black people highly disproportionate death rates — risking both their health and well-being now and in the future.[14] That is partly because people of color are also overrepresented in front-line, essential work with higher infection risk.[15] These trends will only worsen if states cut services in ways that harm families most in need. In contrast, taxing wealth and high incomes more effectively and investing the proceeds wisely can help reverse these trends.

Tax increases at the top are also typically better for state economies during a recession than spending cuts. If states close their shortfalls without raising additional revenue, the budget cuts that they make could prolong and deepen the recession, especially for low-income households and communities of color. States could be forced to limit their purchasing, which could ripple through the economy and harm businesses and communities further. In addition, laid-off teachers, health care workers, and others will spend less and may not be able to meet their basic needs. By contrast, tax increases focused on high incomes and wealth can keep money flowing through states’ economies by staving off layoffs and enabling states to maintain purchasing and vital services such as education and health care. Wealthy individuals with high-salary jobs and savings to draw on generally maintain their spending levels regardless of a tax increase, which isn’t true of those paid low wages.

Four options that many states can implement or improve upon relatively quickly are to strengthen taxation of high personal incomes, valuable real estate, capital gains, and inherited wealth. These approaches build on the fact that the stock market has largely maintained its value, high-salary earners have largely been able to keep their jobs, and high-value homes have largely kept or increased their value.

Several promising state proposals to tax high incomes and wealth, including the California Extreme Wealth Tax developed by Emmanuel Saez and others and a proposed tax on unrealized capital gains in New York state through what is known as a “mark-to-market” system, merit further study and discussion among state policymakers.[16] However, they are much less likely to be available immediately to help close state budget shortfalls and address revenue needs in the coming year. Even if passed, these taxes would require new legal and regulatory frameworks to implement effectively. States can consider enacting such taxes to take effect in a specified future year, along with funding to address regulatory questions. Alternatively, they can consider establishing an interim committee with a clear mandate, funding, and time frame to review such proposals.

Other revenue-raising tax measures that states should consider but that are outside the scope of this report include strengthening the taxation of highly profitable corporations, such as through “combined reporting,” a requirement states can impose that prevents corporations from using certain accounting maneuvers to avoid paying the taxes they otherwise would owe to a state.[17]

States should avoid raising taxes and fees that fall particularly hard on low-income people and people of color. These include criminal legal fees, which too often result in people being jailed simply because they cannot afford to pay a fee. To raise revenue for equity-enhancing investments, some states may want to consider raising sales tax rates or expanding the base of sales taxes even though these tax increases generally fall hardest on low-income families. States should consider taking these steps only as part of an overall tax plan that takes into account families’ ability to pay or that offsets the impact on low-income people by boosting state tax credits targeted to them, such as state earned income tax credits.[18]

Graduated income taxes, through which rates rise with earnings, form a solid foundation for a state’s tax base to ensure that people who earn the most — and are most able to pay — are fairly contributing to a state’s finances. Higher-earning families, which have mostly maintained jobs during the pandemic, are generally more able to contribute right now. However, most state tax systems are upside-down in that those who earn the least pay more, as a share of their income, for schools, roads, disaster response, and other things.[19] These families are disproportionately households of color due to the United States’ history of structural racism, which curtails employment opportunities through many policies and practices such as unequal school funding, mass incarceration, and hiring discrimination.

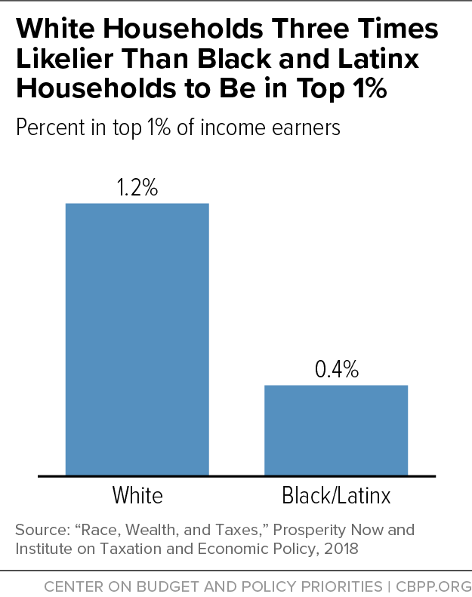

White families are about three times more likely than Black and Latinx families to be among the nation’s top 1 percent of earners, according to one estimate.[20] (See Figure 3.) Most state tax systems deepen these inequities because they take a greater share of the income of low- and middle-income families than of wealthy families. But graduated income taxes aimed at those earning the most can start chipping away at these inequities and contribute to an equitable, antiracist recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting recession. States can increase the top income tax rate, adjust tax brackets and rates so that they fall more on the highest earners, and close personal income tax loopholes.

States can raise the personal income tax rate on households with the highest incomes, through measures such as a higher tax rate on filers with annual income over $1 million (sometimes referred to as a millionaires’ tax) — either permanently or as a pandemic surcharge. States with existing tax brackets focused on high earners can increase the top rate, while states whose top rates start at low or middle levels of income can create new high-income tax brackets that better reflect today’s wage and salary scale;[21] some states have not significantly updated their income tax brackets since their taxes’ establishment in the 1930s. States can also consider a tax on total income for those with incomes above a specified level, as New York and Connecticut have done (explained below).

The step that New Jersey took at the end of September 2020 provides an instructive example for other states. The budget deal signed by the governor features a millionaires’ tax that raises the top income tax rate to 10.75 percent on income over $1 million. This will help reduce economic and racial inequities in the state, which is the ninth-most unequal in terms of the ratio of income held by the top 1 percent versus everyone else.[22]

The new tax is estimated to raise more than $400 million per year, which can help New Jersey respond to the pandemic and set itself on a path to better fund schools, health care, and other priorities. Nearly 100 New Jersey economists and economic policy experts wrote a letter to leading policymakers emphasizing that raising new revenues — particularly from top earners or profitable corporations — is a much sounder response to the recession-driven state revenue decline than cutting health care or schools.[23]

Arizona voters also approved in November 2020 a ballot measure that will make the state’s tax code more equitable while raising hundreds of millions of dollars in badly needed revenue for schools. Arizona’s Proposition 208 (the Invest in Education Initiative) levies a 3.5 percent tax surcharge on income over $250,000 for individuals and $500,000 for joint filers, bringing the top rate to 8 percent on income above those thresholds. The measure will raise a projected $827 million to $940 million a year, all of it dedicated to K-12 schools. It will help the state’s schoolchildren while taking a big step toward educational equity by delivering outsized benefits to children of color and children in families with low incomes.[24]

States can consider additional options to raise income taxes on those earning the most in a state, including:

- Adding a new tax bracket at the top of the income scale. The top rate in 27 of the 42 states with an income tax kicks in at an income level below $100,000 — and below $20,000 in 19 of those states.[25] That means that many states apply the same top tax rate to most or all low-, middle-, and high-income families. States that are doing so should add a top bracket to focus on the highest earners. The economic performance of states that have pursued such a change recently has been very similar to those that did not, and research indicates that differences in tax levels have little to no effect states’ economic health overall.[26] State tax differences also appear to play a negligible role in whether and where people, including high earners, move.[27]

- Requiring high earners to pay the top income tax rate on all of their income (“tax table benefit recapture”). In most state income tax systems, tax rates rise with earnings, and those earning the highest incomes pay the highest tax rate on the portion of their earnings that fall into the highest tax bracket. That means that the lower tax rates that benefit lower- and middle-income taxpayers benefit the wealthy as well. “Tax recapture” requires high-income earners to pay at the top rate on all of their income. For example, Connecticut begins tax recapture at earnings above $200,000, and New York has a recapture provision that begins at about $107,000 in earnings, both depending on filing status.

- Phasing down personal exemptions and standard deductions based on income. Personal exemptions and standard deductions exempt a portion of income from tax. High-income families have less need for these exemptions than other families that earn much less. Some states including Alabama, Connecticut, Maryland, Oregon, and Wisconsin reduce or completely phase out personal exemptions or standard deductions as income increases.

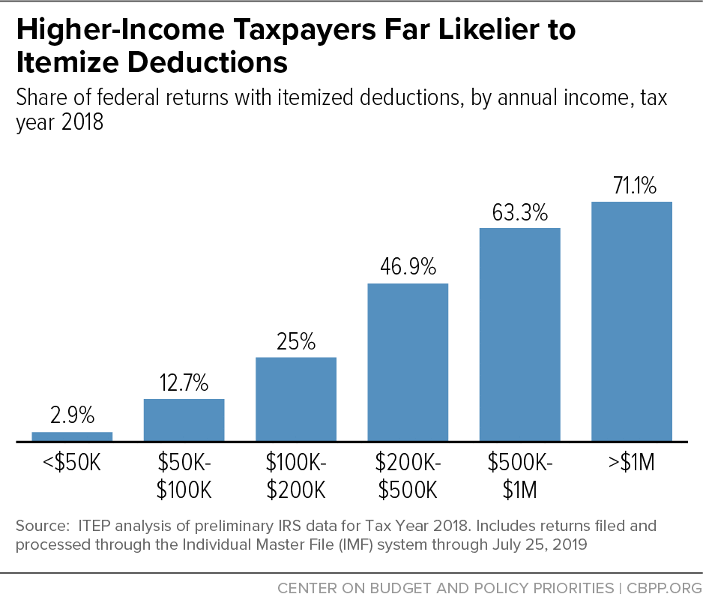

States can also limit or close income tax loopholes that mainly help wealthy individuals and high earners. The 30 states plus the District of Columbia that allow itemized deductions should thoroughly examine them and reduce or eliminate many that are predominantly available to wealthy households.[28] That’s in part because the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 made it less beneficial for low- and middle-income families to itemize at both the federal and state level, so the benefits of itemization now flow even more disproportionately to wealthy families. About 6 percent of federal tax returns with income under $100,000 claimed itemized deductions in 2018, compared to almost half of returns with income greater than $200,000. (See Figure 4 for more detail.) States have several options to reduce, cap, or phase out various deductions:

- Mortgage interest deductions are costly and do not do much to promote homeownership.[29] States can cap the value of the mortgage allowable under the deduction, limit the deduction’s use for second or vacation homes, or repeal it completely.

- Real property tax deductions don’t help the families that struggle most with paying property taxes. States should replace them with property tax “circuit breaker” credits, which ensure that property tax bills are affordable for those on fixed and low incomes and base payment amounts on ability to pay.[30] As of 2018, 18 states and the District of Columbia offered such credits.

- Personal property deductions most commonly cover car taxes, as well as things like manufactured homes and boats. However, benefiting from this deduction requires itemizing, which those facing the highest hurdles to pay property taxes are less likely to do. Even if they do claim the deduction, its benefit rises with earnings, disproportionately helping affluent families. States should repeal it. Also, if a manufactured home is a primary residence, it should be treated as real property in state and federal tax codes rather than as personal property.[31]

In addition, some states offer the same tax breaks as the federal government does for “pass through” business income — that is, income from sources such as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships — which primarily benefit wealthy taxpayers. States should close this loophole.

The pandemic has largely spared high-value homes, and the market for such homes in many areas of the country remains strong.[32] Sales of luxury homes increased 42 percent between June and August 2020 compared to that same period last year, while sales of affordable homes declined more than 4 percent.[33] Increasing taxes on high-value homes directly and on the sale or purchase of such a home — often called a “mansion tax” — is an attractive option for states looking to tax wealth. Home values are easier to measure than other forms of wealth: recent sales of similar properties in the same locality can often be identified, and housing ownership is usually publicly available information. Housing wealth also cannot be easily moved across borders to avoid taxation.[34]

In addition to reducing inequality generally and making state and local tax systems fairer, mansion taxes can help states overcome racial inequities rooted in past racist policies and sustained by ongoing discrimination and bias. Historically, an extensive array of public policies and private practices held back people of color, including government practices that segregated them in low-value neighborhoods and widespread racism in business transactions such as obtaining mortgages. Despite the considerable progress in overcoming these barriers, people of color own much less housing wealth than they otherwise would.[35]

Further, numerous studies have documented that racial discrimination and bias continue to limit housing and job opportunities for people of color.[36] States can use the added revenue from graduated property taxes on high-value property to increase opportunities in lower-income communities of color, particularly during the pandemic, helping people of color overcome these barriers, to the betterment of the country as a whole.

States can improve the taxation of high-value homes either when homes are bought and sold, or through state and local property tax systems.

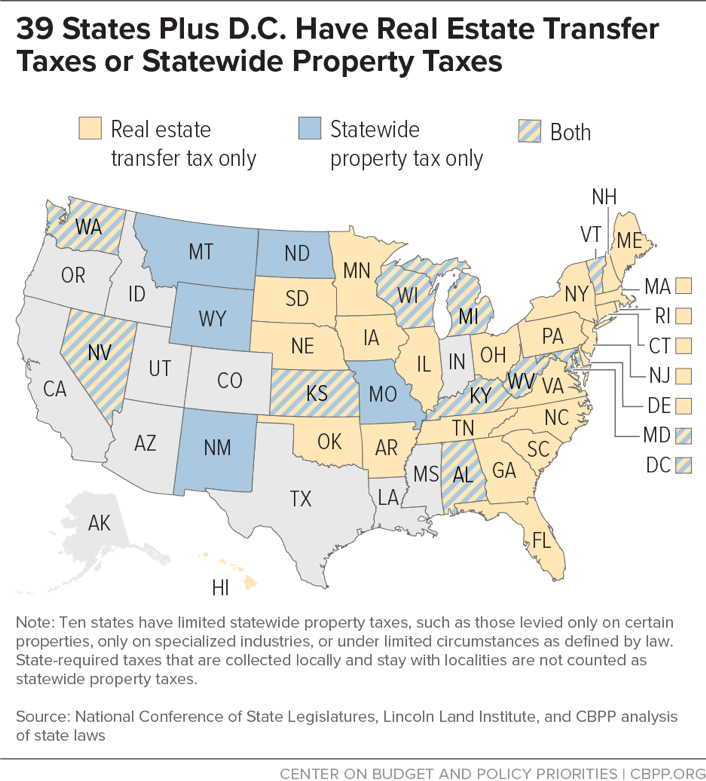

Often called a real estate transfer tax or conveyance tax, this tax — levied upon sale or purchase — is usually paid as a specified percentage of the value of a home sale. For example, Iowa’s real estate transfer tax is $1.60 per thousand dollars of home value with a $500 exemption, so the sale of a $500,000 home would generate $799 in transfer taxes. Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have such taxes, as do a number of localities including Oakland, California and New York City. (See Figure 5.)

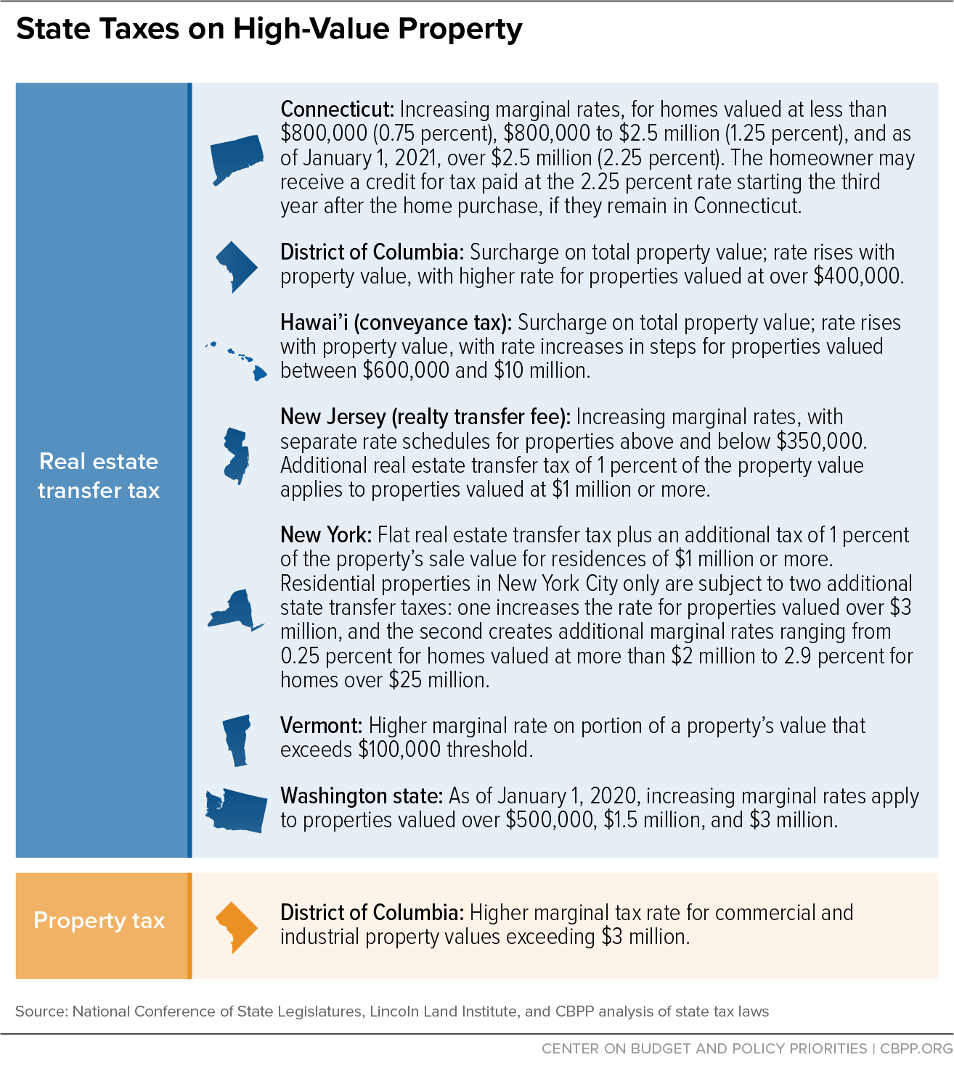

Of those with a real estate transfer tax, seven states — Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawai’i, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, and Washington — levy a surcharge on the highest-value homes or have a bracket structure under which these tax rates rise as the value of the home increases. (See Figure 6.) States can pursue either option. For example, New Jersey and New York each add a 1 percent surcharge to the total sale value of a property of $1 million or more. [37] Vermont and Washington State both have tax brackets based on home values, with higher rates for the portion of a home value above certain thresholds.[38] Marginal tax or surcharge thresholds should be tailored to the real estate market and the relative homes values in each state and be indexed for inflation, to focus the tax on the highest-value homes.

If states do not already have property transfer taxes, they should consider enacting them (although this would face constitutional restrictions in some states[39]). Municipalities, especially those with concentrations of high-value homes, can also consider enacting real estate transfer taxes and focusing them on the highest-value homes if their state permits.

States should also close a loophole in their real estate transfer taxes that exclusively benefits wealthy individuals and profitable corporations. If a limited-liability corporation owns real estate, buyers in some states can purchase a stake in the company instead of the real estate itself and thereby avoid real estate transfer taxes. While this option is most often exercised in buying and selling commercial real estate, it can also include expensive homes. States such as Michigan have closed this loophole by clarifying that a company that owns a “controlling interest” in an entity owning real estate is subject to the tax.[40] Lawmakers proposed to close this loophole in Ohio and Pennsylvania earlier this year.[41]

Creating Progressive State and Local Property Taxes

Another way to tax high-value homes is to add a mansion tax onto a state or local property tax system. Since property taxes are typically levied annually, this form of tax would produce revenue from the owners of expensive homes each year, rather than just when a home is sold, as with real estate transfer taxes. Property taxes are levied at the local level in all states, and 16 states also assess them at the state level. Property taxes are calculated using a formula that assesses the home (which may not reflect its full market value) and multiplies that amount by the state or local tax rate.

Many states also have property tax exemptions, caps, and credits. Circuit breakers, for example, are tax credits that are designed to help people who are paid low wages or otherwise have low incomes afford their property tax bills. At the same time, many states also have overly restrictive property tax limits that hamstring localities’ ability to raise sufficient revenue. This limits localities’ ability to provide adequate services to increase opportunity for their residents, while increasing racial and economic inequities in part by leading many localities to turn to revenue sources that fall harder on lower-income people.[42]

No state has graduated property tax rates for high-value homes (though the District of Columbia has a higher marginal rate for commercial and industrial property valued at over $3 million). Similar to real estate transfer taxes, mansion taxes could be designed to include additional tax brackets aimed at very high-value homes, or an additional tax on the total value of a home if it surpasses a certain amount (i.e., a surcharge). Decisions about the thresholds for such taxes should be made in consideration of a state’s home prices and housing market.

States can also enact additional property taxes for second homes. While no state has done this yet, several have considered it. This option can be particularly attractive in real estate markets where there are many vacation homes or investment properties. In 2015, Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo proposed a surcharge on secondary homes worth more than $1 million.[43] In New York, lawmakers proposed a “pied-a-terre” tax for New York City,[44] which would apply to owners of vacant second homes in New York City worth at least $5 million.

Finally, states can relax or repeal restrictive limits on property taxes. Such limits have provided disproportionate savings to wealthy homeowners, a group that is overwhelmingly white (in part because past government policies contributed to the segregation of people of color in lower-value areas). These limits have also been associated with states shifting toward sales taxes and fees, which fall hardest on those with the least ability to pay. Repealing or relaxing such limits can help rebalance state property taxes, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when people with high-paying jobs and stock market investments have fared better than those with much less. While many property tax limits are written into state constitutions and thus generally require more effort to repeal, some have been enacted by state legislatures directly and are more ripe for change.

The unequal recovery — marked by a rebounding stock market and continued high unemployment especially for workers of color and those with low incomes — reinforces barriers that make it harder for many to make gains. One way states can build more broadly shared prosperity is by strengthening their taxes on realized capital gains: the profits generated when selling an asset such as shares of stock, mutual funds, real estate, or artwork that has grown in value. States can then invest the tax’s proceeds in education, health care, and other building blocks of broadly shared prosperity.

While the value of an asset can increase in many or all of the years that it is owned, states and the federal government tax capital gains only when the asset is sold and the gain is “realized.” For example, consider a taxpayer who bought 100 shares of stock for $10 each (total cost of $1,000) and sold them for $15 each (total value of $1,500). The increase in value of $500 is the amount of capital gains income that the taxpayer realizes.

If the sale occurs within a year of the purchase, the gains are considered short-term capital gains for tax purposes; if more than a year after purchase, they are considered long-term gains. The vast majority of capital gains realized each year are long-term capital gains. Under current state and federal law, these capital gains are reported and taxed as income in the year that they are realized.

The federal government taxes income generated by wealth, such as most realized capital gains, at lower rates than wages and salaries from work. The highest-income taxpayers pay 40.8 percent on income from work but only 23.8 percent on long-term capital gains and stock dividends.[45]

Fortunately, unlike the federal government, most states tax income from investments and income from work at the same rate. However, nine states — Arizona, Arkansas, Hawai’i, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin — do provide tax breaks for all long-term capital gains.[46] Typically, these states allow taxpayers to exclude a portion of their capital gains income from their taxable income or provide a credit equal to a percentage of the taxpayer’s capital gains.[47]

In addition, a dozen states provide tax breaks for capital gains on investments in in-state businesses.[48] A few states have preferences targeted to investments in specific industries like technology businesses in Virginia and the farming industry in Iowa and Wisconsin.[49]

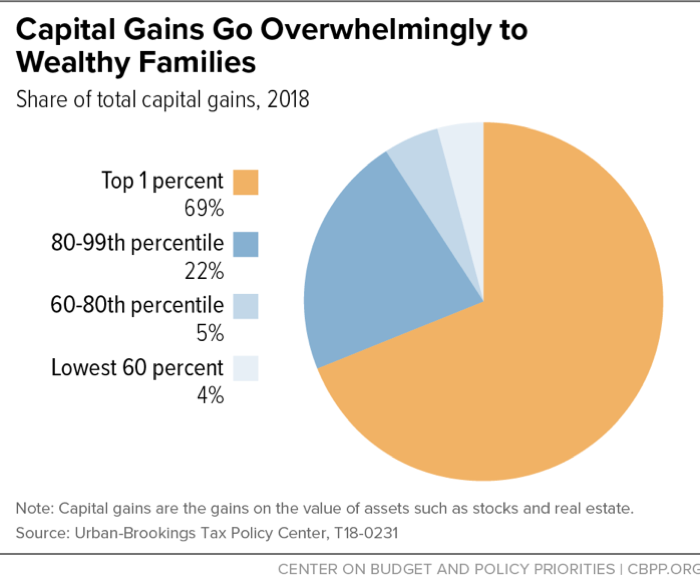

Capital gains are generated by wealth and are therefore highly concentrated: about 80 percent of capital gains income goes to the wealthiest 5 percent of taxpayers, and 69 percent goes to the top 1 percent.[50] (See Figure 7.) As noted, white families are three times likelier than families of color to be in the top 1 percent.[51]

Historically there has been no relationship between federal capital gains taxation and economic growth.[52] In addition, it is highly unlikely that a state capital gains tax break would drive economic investment in the state. The largest category of capital assets is shares of stock, and the companies in which shareholders have a stake could be located in any state or in other countries.

The following proposals for changing state taxation of capital gains could apply to just long-term capital gains or to both long- and short-term gains.[53]

States that provide tax preferences for capital gains income should eliminate this special treatment. Taxing all capital gains at the same rate as ordinary income would mitigate rising wealth concentration and could raise significant revenues. For example, eliminating capital gains preferences in the nine states that provide tax breaks for all long-term capital gains would have raised more than $740 million in 2019, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimates.[54] Rhode Island’s action in 2010 to eliminate its lower capital gains rates is bringing in over $50 million in additional revenue each year.[55]

Other steps that states have taken include New Mexico’s recent reduction of its capital gains preference. The state now taxes 50 percent of realized capital gains compared to the 40 percent previously taxed.

Similarly, in 2010, Wisconsin increased the share of long-term capital gains from non-farm assets that are taxed, from 40 percent to 70 percent. Rhode Island and Wisconsin both scaled back their capital gains tax preferences as part of revenue-raising measures they adopted in the wake of the Great Recession.

The 2017 federal tax law provides special capital gains tax breaks for investments in low-income areas designated as “Opportunity Zones.” These Opportunity Zone tax preferences have proven to be subject to abuse, however, and some relatively affluent areas have been able to qualify as Opportunity Zones. States should consider “decoupling” from these tax breaks, rather than providing similar tax breaks at the state level on top of the federal ones. Decoupling could save states $500 million a year in tax revenue.

The federal Opportunity Zone provisions let investors defer taxes they would otherwise owe on capital gains by “rolling” the capital gains into investment funds — known as Opportunity Zone, or OZ, funds — that then are invested in Opportunity Zone areas.[56] If investors maintain their investments in these OZ funds for a certain number of years, they qualify for additional tax breaks, including a permanent tax exemption on all capital gains they realize through 2047 on their Opportunity Zone investments.

Investors in states where the state income tax code uses the federal definition of income receive this tax break automatically on their state income taxes as well. This reduces state tax revenue — unless a state acts to decouple from the federal tax break. We recommend that states in which this tax break now applies as a result of the state tax code’s linkage to the federal tax code take action to decouple from this tax break.

Impose a Pandemic Surcharge or Raise the Capital Gains Rate Permanently

States considering raising their tax rate on capital gains income can do so either as a temporary pandemic surcharge or as a permanent tax-rate increase. States also can consider levying a somewhat higher tax rate on capital gains than on wages and salaries. Doing so could reverse a modest portion of the federal government’s large and unproductive tax break for long-term capital gains while still resulting in a total capital gains tax rate — state and federal combined — that is below the combined federal and state tax rate on ordinary income.[57] States that have adopted or may be considering some variant of this approach include:

- Massachusetts, which taxes short-term capital gains at 12 percent, more than double the 5 percent rate on ordinary income.

- Maryland and Connecticut, where legislators seriously considered surtaxes on capital gains last year. Maryland’s House Ways and Means Committee considered a 1 percent surtax on capital gains income, with the resulting revenues to be used to boost state support for K-12 education. The Connecticut legislature’s Progressive Caucus agenda included a plan to shift some of the responsibility for taxes in the state from low- and middle-income taxpayers to wealthy households by raising tax rates on both capital gains and very high salaries and wages to finance a new child tax credit and an expanded earned income tax credit. Neither of these efforts were ultimately successful.[58]

Finally, states with no broad-based income tax can still tax capital gains income. Currently, only one state without an income tax (New Hampshire) taxes capital gains. The remaining non-income-tax states could levy a tax on just this type of income, as Washington State recently considered.[59] The proposed capital gains tax there would have been paid almost entirely by the wealthiest 1.2 percent of households in the state.[60]

The lion’s share of wealth in America has long been in the hands of very few. The top 1 percent of households own almost 40 percent of the country’s wealth. The net worth of the wealthiest 10 percent alone is four times that of the other 90 percent.[61] The pandemic has worsened this unequal concentration of wealth. While many low- and moderate-income families have watched their savings evaporate as jobs disappear, the value of many stock portfolios and expensive homes of the wealthy have continued to grow.

The way that states and the federal government tax inherited wealth contributes to this wealth inequality. Many states have no estate or inheritance tax, and the federal government taxes only the inheritances of the very wealthy, with the first $11.6 million of an estate for an individual — effectively $23.2 million for a couple — being entirely exempt from the estate tax in 2020.[62] (These thresholds are adjusted annually for inflation.)

Low or no taxes on inheritances make it easier for wealthy families to pass on wealth, contributing to growing concentrations of wealth and reducing the revenues available for investment in schools, transportation, and health care, which in turn creates barriers to economic opportunity for people in families with low or no savings.

Ways that states can begin to reverse this trend include the following:

- States with an estate tax can raise their rates or lower the threshold at which the taxes apply.

- States without such a tax can enact a new tax on inherited wealth.

- States also can eliminate “stepped-up basis” for taxing inherited assets. Under current state and federal law, people who inherit assets such as stocks, bonds, or real estate pay no taxes on any appreciation of those assets that occurred before they inherited them. (Technically, the value of those assets is “stepped up” from the original purchase price to their value on the date of the estate owner’s death.)

An estate tax is a tax on property (cash, real estate, stock, and other assets) transferred from deceased persons to their heirs. A state applies a tax rate to the value of an estate that exceeds a certain threshold; both the rate and the exemption threshold differ by state. A typical state with an estate tax exempts $2 to $5 million per estate[63] and applies rates ranging from 1 percent to 16 percent to the value of property left to any heirs except a spouse. On average, fewer than 3 percent of estates — very large ones owned by the wealthiest individuals — owe state estate taxes.

Some states levy an inheritance tax rather than an estate tax. It is levied on the recipients of the estate (the heirs) instead of the deceased person’s estate.

Consider an unmarried woman who owns a house, stocks, cash, and other assets worth $30 million and leaves those assets to her three children in equal shares upon her death. In a state with an estate tax, the tax is based on the value of the estate and is subtracted from the estate before the estate’s distribution to the heirs. In a state with an inheritance tax, the children each receive their $10 million bequest and then owe inheritance tax on that bequest.

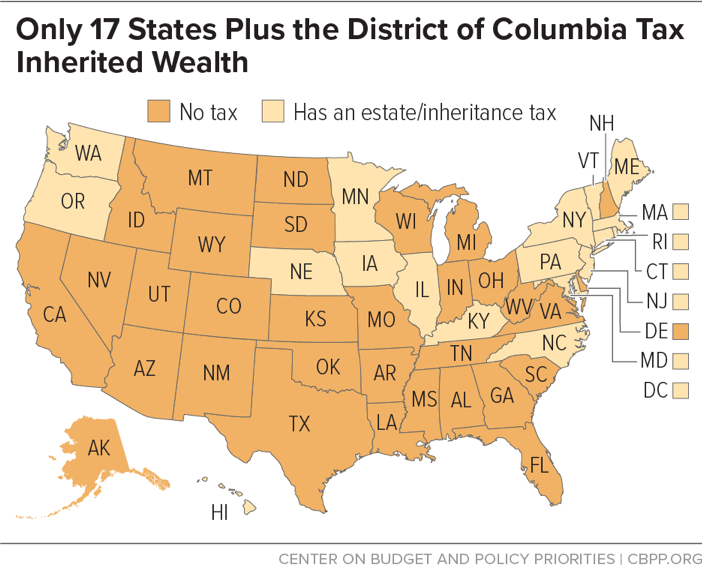

As of October 2020, only 17 states and the District of Columbia levy either an estate or an inheritance tax. (See Figure 8.) These taxes generate about $4.5 billion per year. If all states levied an estate tax, they could generate an additional $3.5 to $11 billion, depending on the exemptions and the tax rates.[64]

States that lack an estate or inheritance tax could enact new taxes on inherited wealth by adopting a state estate or inheritance tax. (Until 2001, every state levied some form of estate tax.) Hawai’i and Delaware reinstated estate taxes in the wake of the Great Recession, although Delaware has since repealed it.

States that have an estate tax could secure more revenue by raising their tax rates or lowering the thresholds at which the estate taxes began to apply. For example:

- Hawai’i strengthened its estate tax in 2019 by adding a higher rate for the largest estates.

- Under the 2017 federal tax law, the federal estate tax exemption threshold was increased and now stands at $11.6 million for individuals and $23.2 million for married couples. The District of Columbia, Maryland, Maine, and New York have since delinked their thresholds from the federal one, making Connecticut the only state still linked to the federal threshold. (Its estate tax threshold is scheduled to increase to the federal threshold in steps over the next few years.)

Under current state and federal law, people who inherit assets such as stocks, bonds, or real estate pay no taxes on any appreciation of those assets that occurred before they inherited them. (Technically, the value of those assets is “stepped up” from the original purchase price to their value on the date of inheritance.) As a result, a large share of capital gains is never taxed.

Consider a taxpayer who bought 100 shares of stock for $10 each and held them until her death, when their value had risen to $50 per share. She left them to her daughter, who sold them a number of years later, after their value had risen to $55 per share. Under current law, the daughter’s taxable capital gains would reflect the $5-per-share increase that occurred while she owned the stock, not the $45-per-share increase that occurred since her mother bought it.

State estate taxes used to help compensate for stepped-up basis by taxing assets at the time they were inherited. But most states no longer have an estate tax, and the tax thresholds in states that do have the tax are generally so high that very few estates actually owe it.[65]

Stepped-up basis primarily benefits the wealthiest families because they have the most unrealized capital gains. Also, they can afford to hold on to their assets until they die and pass them on to their heirs rather than use them to pay expenses in retirement. Families of color have lower savings than white families and are less likely to have pension income. They consequently are less likely than white families to benefit from this generous tax break. Some two-thirds of Black and Latinx working-age households own no assets in a retirement account, compared to 37 percent of white households.[66]

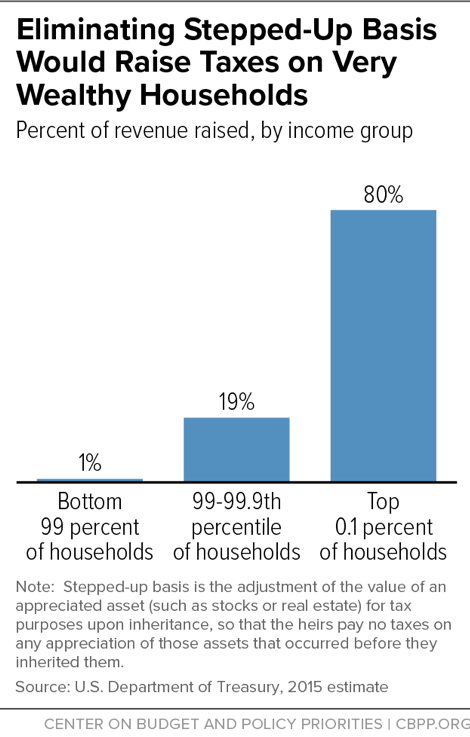

Eliminating stepped-up basis would result in taxation of an asset’s full increase in value from the time of its purchase to the time it is sold. This would have a very progressive impact: fully 99 percent of the revenue from eliminating stepped-up basis would come from the top 1 percent of filers, and 80 percent would come from the top 0.1 percent, according to the Treasury Department.[67] (See Figure 9.)