- Home

- State Supermajority Rules To Raise Reven...

Policy Basics: State Supermajority Rules to Raise Revenues

States with supermajority requirements to pass tax increases tend to have similar levels of taxation to states without them. Supermajority rules can weaken a state’s capacity to properly handle its finances by protecting outdated tax breaks, expanding the power of special interests, and limiting states’ options in responding to recessions.

Legislatures in most states (34 states plus the District of Columbia) can approve tax bills with a simple majority vote in each house, the same margin required for practically every other bill. In the other 16 states, some or all tax bills require a supermajority vote of each house.

Most states with supermajority requirements impose them only in limited circumstances, but in seven states, the constitution requires a supermajority vote of each house, plus the governor’s signature, to enact any bill that includes a tax increase. Delaware, Mississippi, and Oregon require a three-fifths vote of each house, while Arizona, California, Nevada, and Louisiana require a two-thirds vote of each house.

Little Difference in Tax Levels Between Supermajority and Non-Supermajority States

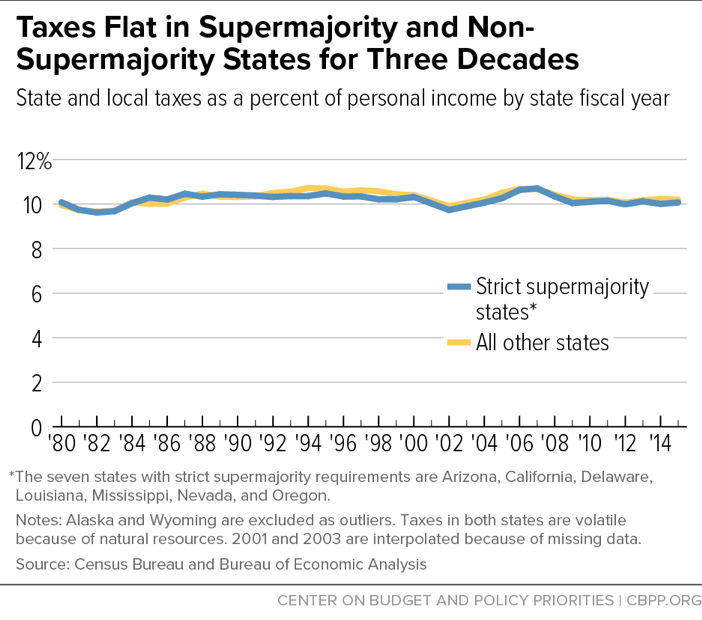

States with strict supermajority requirements levy taxes at a nearly identical level as other states, on average. In both groups of states, state and local taxes have remained flat as a share of personal income for three decades.

States with strict supermajority requirements levy taxes at a nearly identical level as other states, on average. In both groups of states, state and local taxes have remained flat as a share of personal income for three decades (see chart).

That’s because states don’t need supermajority requirements to ensure that taxes will remain manageable, that major tax increases will be rare, and that lawmakers will think very carefully before raising taxes.

States usually enact major tax increases only in the aftermath of recessions, when revenues have fallen well short of the cost of maintaining public services — and generally accompany them with deep spending cuts. Moreover, states almost always offset recession-driven tax increases by cutting taxes in good economic times. For example, a majority of states enacted tax changes that raised additional revenue immediately after the Great Recession (2007-2009), and a number of states began cutting taxes after 2010.

Beyond being unnecessary, supermajority rules can weaken a state’s capacity to properly handle its finances by:

Beyond being unnecessary, supermajority rules can weaken a state’s capacity to properly handle its finances, such as by protecting outdated and wasteful tax breaks.

- Protecting outdated and wasteful tax breaks. In many cases, repealing a tax break is considered a tax increase subject to the supermajority requirement. This means that costly deductions, credits, and other tax expenditures that don’t work as intended or have outlived their usefulness have more protection than other types of spending, which lawmakers can change by a simple majority vote.

- Shifting costs from some residents to others. When raising taxes and repealing tax breaks are subject to supermajority requirements, lawmakers are more likely to raise needed revenue by hiking fees, tuition, and other levies not subject to the requirements. They are also more likely to reduce support for local governments, which may need to raise property taxes as a result. Such actions shift the cost of government from some taxpayers to others — students, Medicaid recipients, and homeowners, for example. And because these charges generally aren’t based on a person’s income or ability to pay, rising fees most affect low- and middle-income families.

- Raising the cost of capital investments. Research shows that investors are less willing to buy bonds from states with supermajority tax requirements. This is because such rules reduce states’ flexibility to raise revenue, making them less trustworthy borrowers in the eyes of investors and bond rating agencies. Supermajority states thus are more likely to have lower bond ratings, forcing them to make higher interest payments to investors and raising the cost of new schools, university facilities, and other bond-financed projects.

-

In supermajority states, a small minority of lawmakers and special-interest lobbyists can hold even the most popular legislation hostage.

Expanding the power of special interests. In supermajority states, a small minority of lawmakers and special-interest lobbyists can hold even the most popular legislation hostage, demanding narrow concessions or the inclusion of expensive pet projects. And supermajority rules make it much easier for lobbyists representing a few corporations or other taxpayers to protect existing tax breaks for these narrow interests.

-

Limiting lawmakers’ options during recessions. The best approach to combating recession-induced budget gaps is usually a balanced one that includes both revenue increases and targeted spending cuts. This approach cushions the decline in economic activity, since fewer public employees are laid off and fewer private companies lose government contracts, and helps maintain supports for workers, such as unemployment insurance, when job losses are highest. By making it harder to raise taxes, supermajority rules encourage states to close gaps mostly if not entirely through spending cuts, which can inhibit a recovery.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.