- Home

- Tax Credits For Individuals And Families

- States Can Adopt Or Expand Earned Income...

States Can Adopt or Expand Earned Income Tax Credits to Build a Stronger Future Economy

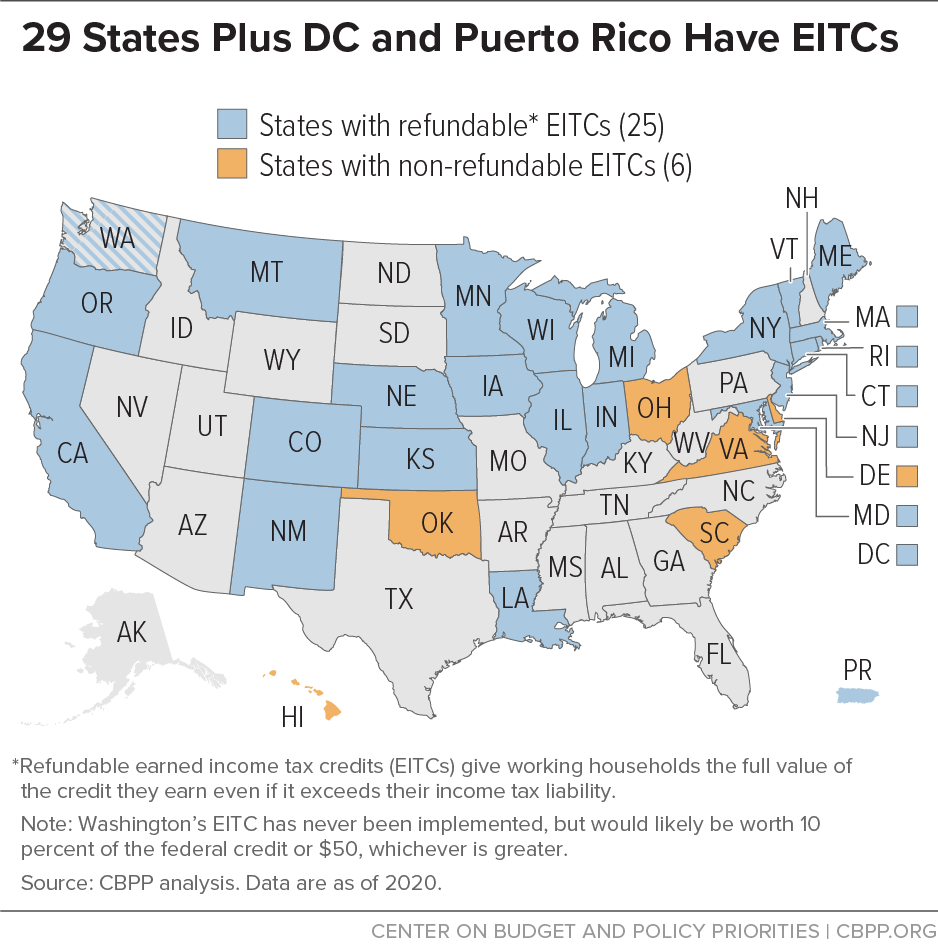

Twenty-nine states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have enacted their own version of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to help working families paid low wages meet basic needs.[1] State EITCs build on the success of the federal credit by keeping people on the job and reducing hardship for working families and children. This important state support also extends the federal EITC’s well-documented long-term positive effects on children, boosting the nation’s future economic prospects.

State EITCs provide extensive benefits to children, families, and communities, and are straightforward to administer and to claim. Lawmakers in states without their own EITC should consider enacting one. The small number of states that have cut back or eliminated their credits should reverse course, and states that have limited their credits so that they only offset income taxes should expand them to help offset the full range of state and local taxes that low-income households pay. In addition, states can extend the credit to certain workers who currently are ineligible, such as younger workers not claiming children and those filing taxes with an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN). All of these steps would substantially enhance the credits’ impact. By investing in an EITC, states can make a real difference in the lives of working families with low and moderate incomes.

Why Consider an EITC?

Many working families with children struggle to make ends meet on low wages. A full-time job at the federal minimum wage yields about $15,000 ― often insufficient income for a family to afford basic necessities. The EITC, a federal tax credit for people earning low and moderate pay, boosts income and improves the outlook for children in low-income households. It also helps women and communities of color — two groups that disproportionately work in low-wage jobs — see more of the fruits of their labor and share more fully in the benefits of economic growth. State lawmakers can build on the proven effectiveness of the federal EITC to help address low wages with a state-level credit. Like the federal EITC, state EITCs:

- Help working families make ends meet. Many low-wage jobs fail to provide enough income on which to live. “Refundable” EITCs, which give working households the full value of the credit they earn even if it exceeds what they owe in income taxes, provide workers struggling on low wages with a needed income boost that can help them meet basic needs.

- Keep families working. Refundable EITCs help working families paid low wages afford the very things that allow them to continue working, like child care and transportation. Research demonstrates that unmarried mothers, in particular, work more hours as a result of the credit. That extra time and experience on the job can translate into better opportunities and higher pay over time.[2] Three in five filers who receive the federal credit use it temporarily — for just one or two years at a time.[3]

- Reduce poverty, especially among children. Eight million children in working families lived below the official poverty line (about $25,500 for a family of four) in 2018;[4] millions of families modestly above that income level have difficulty affording food, housing, and other necessities. The federal EITC is one of the nation’s most effective tools for reducing the struggles of working families and children, particularly for unmarried women with children. It kept 5.6 million people — over half of them children — out of poverty in 2018, and helped many with somewhat higher incomes make ends meet. And by boosting the employment of working-age parents, particularly women, the EITC also increases their Social Security retirement benefits and thereby reduces poverty among seniors.[5] State EITCs build on that record.

- Have a lasting effect. A growing body of research finds that young children in low-income families that get an income boost like the EITC provides tend to do better and go further in school because the additional resources help parents better meet their needs. Research suggests that boys and children of color particularly benefit.[6] Children growing up poor tend to work less and earn less as adults relative to better-off peers; conversely, children receiving additional income such as from the EITC are likelier to see their employment and earnings prospects improve.[7] This helps communities and the economy because it means more people and families are on solid ground over the long haul.

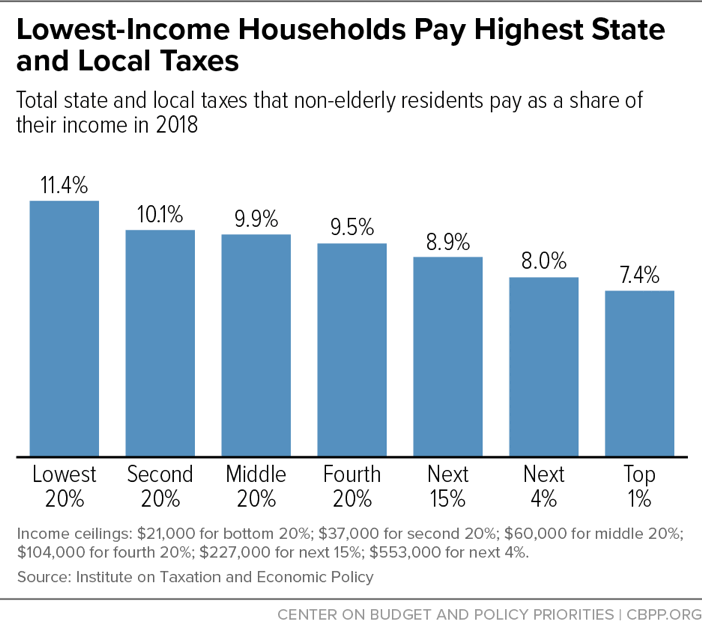

State EITCs can also help counteract the substantial state and local taxes paid by households with low and moderate incomes, especially relative to households with higher incomes. Such families in almost all states pay more as a share of their income in state and local taxes than do upper-income families (see Figure 1). This imbalance reflects states’ heavy reliance on sales, excise, and property taxes, all of which fall more heavily on families with lower incomes. Some states have increased their reliance on these taxes in recent years by shifting their tax systems away from income taxes, pushing an even larger share of the costs of roads, schools, and the like to households earning the least.

States Continue Building on Federal Credit

State EITCs made significant gains in 2019, as California, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon all expanded their credits. California’s expansion provides an additional $1,000 credit for each eligible family with at least one child under age 6, raises the credit’s income limit, and increases the credit for families receiving small credits. Maine raised the credit from 5 percent of the federal EITC to 12 percent for families with children, and to 25 percent for families without dependent children. Minnesota doubled the maximum credit for workers without dependent children and raised the income limit for those workers. New Mexico raised its credit from 10 percent of the federal EITC to 17 percent for the 200,000 families receiving it. Ohio raised its non-refundable credit from 10 percent of the federal EITC to 30 percent and removed a cap on the credit that no other state had. Oregon raised the credit from 8 percent of the federal EITC to 9 percent, and from 11 to 12 percent for families with a child under age 3.

Box 1: Recent Examples of States Creating or Expanding EITCs

California extended its credit to self-employed workers (2017) and to younger workers and full-time workers earning the state minimum wage (2019). It also created an additional $1,000 credit for families with young children (2019). |

Minnesota boosted the total value of its credit by 25 percent (2014), extended eligibility for the childless workers’ EITC to workers aged 21-24 (2017), and both doubled the maximum credit for childless workers and raised the income limit for those workers (2019).

|

Hawaii enacted a non-refundable credit worth 20 percent of the federal credit (2017).

|

Montana enacted a refundable EITC worth 3 percent of the federal credit (2017).

|

Iowa doubled its credit to 14 percent of the federal EITC (2013) and raised it to 15 percent (2014).

|

New Jersey raised its credit from 20 percent of the federal EITC to 30 percent (2015), then to 35 percent (2016), and then to 40 percent in 2018.

|

Illinois raised its EITC from 10 percent of the federal credit to 14 percent (2017) then to 18 percent (2018).

|

Oregon raised its credit from 6 percent of the federal EITC to 8 percent (2013), and then to 9 percent (2019). It also raised its EITC for families with very young children to 11 percent of the federal credit (2016) and then to 12 percent (2019).

|

Maine made its credit refundable (2015), then raised it from 5 percent of the federal EITC to 12 percent for families with children in the home and to 25 percent for families without children (2019).

|

Puerto Rico enacted a local EITC (2018).

|

Maryland raised its credit from 25 percent of the federal EITC to 28 percent over four years (2014), and extended the credit to younger workers without children in the home (2018).

|

New Mexico raised its credit from 10 percent of the federal EITC to 17 percent (2019).

|

Rhode Island expanded its credit for most recipients by making it fully refundable, though the state also cut the credit from 25 percent of the federal EITC to 10 percent (2014). Rhode Island later raised its credit to 12.5 percent of the federal EITC (2015) and to 15 percent (2016).

|

Washington, D.C. became the first jurisdiction to expand the credit for workers without dependent children in the home, extending the credit’s reach to childless workers with somewhat higher incomes and setting its value at 100 percent of the federal credit (2014).

|

States’ successes in 2019 build on earlier advances. Puerto Rico signed its new local EITC into law in 2018. Louisiana increased its credit from 3.5 of the federal credit to 5 percent, Massachusetts from 23 to 30 percent, New Jersey from 35 to 40 percent, and Vermont from 32 to 36 percent. California and Maryland also expanded access to the credit for some groups previously ineligible. Californians aged 18 and older without dependents can now receive the credit, and the credit’s income limit will increase both for workers with children in the home and those without. The changes in California will benefit an estimated 700,000 working households. In Maryland, an estimated 40,000 workers without dependents — mostly ages 18-24 —can now receive the credit. Many other states continue to enact and improve their credits. (See Box 1.)

Unfortunately, several states have cut their credits back. Most recently, in 2017, Connecticut reduced its credit from 27.5 percent of the federal credit to 23 percent, well below its original 30 percent level.[8]

Because state lawmakers have moved to support working families through state EITCs, almost half of recipients of the federal EITC now also are eligible for a state credit. State EITCs boost the earnings of 13 million working families by more than $5 billion annually.

EITC’s Design Boosts Work

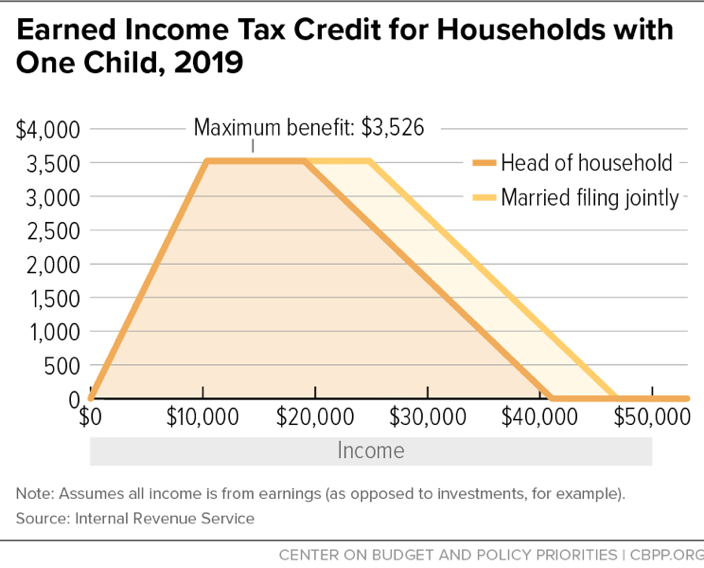

The EITC goes to working families and is designed to boost work. For families with very low earnings, the EITC increases as earnings rise. Working families with children earning up to about $41,000 to $56,000 (depending on marital status and the number of children in the family) generally qualify for a state EITC, with the largest benefits going to families with incomes between about $10,000 and $24,000. Workers without children can also qualify in most states, but the benefit is small, and they can receive it only if their income is below about $15,000 ($21,000 for a married couple).

The EITC’s design also reflects the reality that larger families face higher living expenses than smaller families: the maximum benefit varies for families with one, two, and three or more children. For example, the maximum federal benefit for families with two children in tax year 2019 is $5,828, compared to $3,526 for families with one child. (As with most other federal tax provisions, the IRS adjusts EITC benefit amounts and eligibility levels each year for inflation.) [9] However, recent federal tax changes will erode somewhat the value of the credit over time (see Box 2).

Figure 2 shows how the federal EITC works for a single-parent family with one child earning the minimum wage in 2019 (about $15,000 a year for full-time, year-round work). For every dollar she earns, she gets 34 cents in EITC benefits. The value of the credit continues rising at that rate until her earnings reach $10,370. At that point, she receives the maximum benefit of $3,526. Once her earnings exceed $19,030, the credit shrinks by about 16 cents for each additional dollar of earnings until reaching zero at about $41,000 in earnings.

Box 2: Recent Federal Tax Changes Somewhat Weaken the EITC

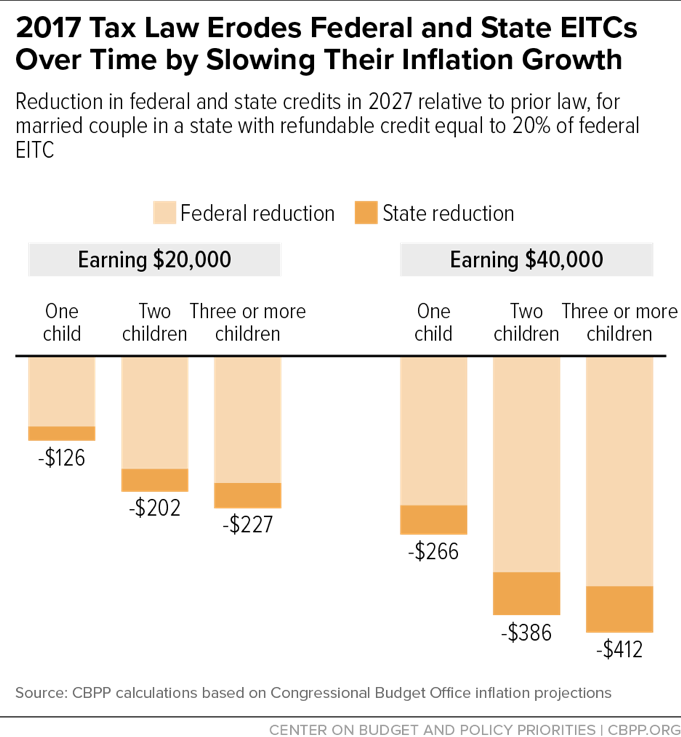

The 2017 federal tax law, which took effect in 2018, erodes the EITC’s value over time by using a different measure of inflation, the “chained” Consumer Price Index, to adjust the EITC’s parameters each year. Using this new measure, the maximum value of the federal credit will rise more slowly over time (on average, by a few tenths of a percentage point each year) than under previous law.a (See chart.) This change will similarly reduce the value of state EITCs that rely on the federal credit and hence on the federal inflation adjustment, as most do. States can mitigate this effect by increasing their credits or putting in place incremental increases over time.

a Chuck Marr, “Instead of Boosting Working-Family Tax Credit, GOP Tax Bill Erodes It Over Time,” CBPP, December 21, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/instead-of-boosting-working-family-tax-credit-gop-tax-bill-erodes-it-over-time.

Most States Model Their EITCs on Federal Credit

Nearly all state EITCs are modeled directly on the federal EITC: they use federal EITC eligibility rules and are a specified percentage of the federal credit. (The percentages are shown in Table 1.)

A few state credits, however, differ somewhat from the federal credit:

- California’s EITC, enacted in 2015, is available to only a share of workers who can claim the federal credit — those with incomes less than about $30,000.[10] Starting in 2018, workers 18 and older not raising children in their home can get the credit. Workers with a child under age 6 are also eligible to receive a new $1,000 Young Child Tax Credit.

- Indiana uses old federal guidelines that exclude recent expansions and improvements to the federal credit.

- Maryland eliminated, as of 2018, the lower age limit of 25 for workers without children in the home. (The federal credit stipulates that workers without children in the home must be between 25 and 64 to receive the federal EITC.)

- Massachusetts permits survivors of domestic abuse who are separated from a spouse to receive the credit, many of whom would otherwise be ineligible.

- Maine allows young workers aged 18 to 24 not raising children in the home to claim the credit, as of 2019.

- Minnesota uses federal eligibility rules, and its credit parallels major elements of the federal structure, but it has its own schedule for the income levels at which the credit phases in and out. With its 2017 expansion, it also allows younger workers aged 21-24 without children in the home to claim the state credit.

- New York offers an EITC to non-custodial parents.

- Puerto Rico enacted a local EITC in 2018. Puerto Rican families cannot claim the federal EITC, so the credit could not be set as a percentage of the federal EITC despite its similar design. Like state credits, it is substantially smaller than the federal EITC. Unlike most state credits, it phases in and out more quickly than the federal credit.

- Washington, D.C.’s expanded EITC for workers without dependent children phases in following federal guidelines, but the maximum credit extends to 150 percent of the poverty line (for an individual), and the credit fully phases out entirely at twice the poverty line. D.C. also offers an EITC to non-custodial parents.

Twenty-three states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico follow the federal practice of offering a fully refundable EITC. (See Figure 3.) Without this feature, state EITCs would fail to offset the other substantial state and local taxes that families pay, such as sales taxes, property taxes, and others. Refundability is the reason that the EITC is so effective at boosting income and reducing hardship. It lets families keep more of what they earn and helps them keep working despite earning low wages.

Box 3: Expanding EITC for Workers Not Raising Children Would Improve Equity

Expanding the EITC for workers not raising children in their home would ensure that the credit offers a hand up to more workers struggling to get by on low wages.a The federal EITC for these workers is very limited and small, even though they are integral members of their communities and local economies. Many are non-custodial parents or future parents.

Partly because the EITC for these workers is so small, they are the lone group that federal income and payroll taxes push into or deeper into poverty. Proposals to expand the federal credit for these workers — such as the nearly identical proposals of former President Obama and former House Speaker Paul Ryan — would help address this problem.b

An expansion also would modestly reduce the income disparity between high- and low-income households by boosting incomes at the bottom. Some 13 million workers would benefit from the Obama/Ryan proposals — people who do important but low-paid work in hospitals, schools, office buildings, and construction sites across the country. Just under half of them are women, more than half are under age 35, and more than half are white. People of color would benefit substantially, since they are likelier than whites to have low incomes. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) people also would benefit, both because LGBTQ adults are more likely to earn low wages than heterosexual adults and because same-sex couples are less likely to be raising a qualifying child than other families.c

In addition to making work pay and boosting incomes at the bottom of the wage scale, an expansion of the EITC for workers not raising children in the home would likely produce other benefits. Research indicates that it can increase employment rates among workers not raising children,d as EITC expansions in the early 1990s did among single mothers. It also could strengthen attachment to the labor force among less-educated, younger workers, whose rates of employment and incomes have fallen over the last couple of decades.

States need not wait for an expansion of the federal credit for childless workers. The District of Columbia expanded its own EITC to fully match the federal credit for workers without children in the home in 2014. In 2017, Minnesota expanded its Working Families Credit so that young workers without dependent children can qualify at age 21. In 2018, California extended its EITC to workers 18 and over, and Maryland eliminated the credit’s lower age limit. In 2019, Maine extended its credit to workers 18-24 without children in the home and enabled them to receive a credit worth 25 percent of the federal EITC. Several other states are considering similar expansions.

a Chuck Marr, “EITC Could Be Important Win for Obama and Ryan,” CBPP, November 16, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/eitc-could-be-important-win-for-obama-and-ryan.

b See Chuck Marr et al., “Strengthening the EITC for Childless Workers Would Promote Work and Reduce Poverty,” CBPP, April 11, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/strengthening-the-eitc-for-childless-workers-would-promote-work-and-reduce.

c “Paying an Unfair Price: The Financial Penalty for Being LGBT in America,” Center for American Progress and Movement Advancement Project, http://www.lgbtmap.org/file/paying-an-unfair-price-exec-summary.pdf, and Census Bureau, Characteristics of Same-Sex Couple Households: 2005 to Present.

d Cynthia Miller et al., “Boosting the Earned Income Tax Credit for Singles: Final Impact Findings from the Paycheck Plus Demonstration in New York City,” MDRC, September 2018, https://www.mdrc.org/publication/boosting-earned-income-tax-credit-singles.

The remaining six states’ EITCs — those in Delaware, Hawaii, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Virginia — are available only to the extent that they offset a family’s state income tax. Thus, while these non-refundable EITCs reduce income taxes for families that owe them, they do not make up for other taxes that working families pay. Nor do they do much to help keep families working and out of poverty.

| TABLE 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Earned Income Tax Credits, 2019 | |||||

| State | Percentage of Federal Credit | Refundable? | Eligibility Expansions Beyond the Federal Credit | ||

| California | 85% of federal credit, up to 50% of the federal phase-in rangea | Yes | Workers without children in the home 18 and older; $1,000 Young Child Tax Credit for families with children under 6 | ||

| Colorado | 10% | Yes | |||

| Connecticut | 23% | Yes | |||

| Delaware | 20% | No | |||

| District of Columbiab | 40%/ 100% |

Yes | Adults without dependent children with incomes up to twice the poverty line, and non-custodial parents | ||

| Hawaii | 20% | No | |||

| Illinois | 18% | Yes | |||

| Indianac | 9% | Yes | |||

| Iowa | 15% | Yes | |||

| Kansas | 17% | Yes | |||

| Louisiana | 5% | Yes | |||

| Maine | 12%/25%d | Yes | Workers 18-24 without children in the home | ||

| Marylande | 28% | Yes | Workers without children in the home under age 24 | ||

| Massachusettsf | 30% | Yes | Survivors of domestic abuse who would otherwise be ineligible | ||

| Michigan | 6% | Yes | |||

| Minnesotag | Avg. 37% | Yes | Workers 21-24 without children in the home | ||

| Montana | 3% | Yes | |||

| Nebraska | 10% | Yes | |||

| New Jersey | 40%h | Yes | |||

| New Mexico | 17% | Yes | |||

| New York | 30% | Yes | Non-custodial parentsi | ||

| Ohio | 30% | No | |||

| Oklahoma | 5% | No | |||

| Oregonj | 9%/12% | Yes | |||

| Rhode Island | 15% | Yes | |||

| South Carolinak | 41.67% | No | |||

| Vermont | 36% | Yes | |||

| Virginia | 20% | No | |||

| Washingtonl | 10% (when implemented) | Yes | |||

| Wisconsin | 4% - one child 11% - two children 34% - three children No credit - childless workers |

Yes | |||

| Puerto Rico | Follows a separate schedule, credit between $300-$2,000 based on family sizem | Yes | |||

a California’s credit is available to working families and individuals with wage income below $30,000 depending on family size. The credit is worth 85 percent of a household’s federal EITC until household income reaches half of the level at which the federal credit is fully phased in; it then begins phasing out at varying rates, depending on family size. In 2019, the maximum credit ranges from $240 for workers without dependent children to about $3,000 for workers with three or more children, plus a new $1,000 Young Child Tax Credit for families with children under 6. The value of the credit is set each year by the legislature.

b The District of Columbia now offers a credit equal to 100 percent of the federal EITC to adults without dependent children who have incomes up to twice the poverty line (for an individual). The D.C. EITC also counts the children of non-custodial parents, as long as the worker is aged 18 to 30 and the worker pays child support and is up to date on those payments.

c Indiana decoupled from federal provisions expanding the EITC for families with three or more children and raising the income phase-out for married couples.

d Maine’s credit is 12 percent for families with children in the home, and 25 percent for families without children in the home (these families receive a much smaller federal credit)

e Maryland also offers a non-refundable EITC set at 50 percent of the federal credit. In effect, taxpayers may claim either the refundable credit or the non-refundable credit, but not both.

f Massachusetts’ credit increased to 30 percent of the federal credit starting in 2019. In addition, survivors of domestic violence can file their own tax returns and remain eligible for the EITC. (Otherwise, survivors separated from a spouse must either file joint tax returns with an abuser or claim head of household status, for which they may not be eligible.)

g Minnesota’s credit, unlike the other credits shown in this table, is structured as a percentage of income rather than a percentage of the federal credit. In 2019, Minnesota doubled the maximum credit for workers without children in the home and raised the income limit for those workers. Families with three or more children will receive a larger credit (previously they received the same credit as families with two children), and families with one or two children will see a small increase. The figure shown here for the Minnesota credit reflects total projected state spending for the state’s Working Family Credit divided by projected federal spending on the EITC in Minnesota, as modeled by Minnesota’s House Research Department. This figure fluctuates from year to year.

h New Jersey’s credit will reach 40 percent of the federal credit starting in 2020.

i New York non-custodial parents who meet certain requirements may claim 20 percent of the federal credit that they would have received with a qualifying child, or 2.5 times the federal credit for workers without qualifying children.

j In 2016, Oregon lawmakers increased the credit for workers with children 3 years and younger to 11 percent of the federal credit.

k South Carolina’s EITC will be phased in in six equal installments starting in 2018, to reach 125 percent of the federal credit by 2023. This credit is non-refundable and is less generous than a 5 percent refundable EITC, because workers with very low incomes tend to have little to no tax liability.

l Washington’s EITC has never been implemented, but would likely be worth 10 percent of the federal credit or $50, whichever is greater.

m Puerto Rico’s EITC, while similar in design to the federal credit, has different parameters. Its EITC phases in at between 5% and 12% of earnings, depending on family size, and begins phasing out at the same rate at between $13,000 and $18,000 depending on family size. The maximum credit is $2,000, which is much smaller than families would receive on the mainland. (Puerto Rico residents are ineligible for the federal EITC.) For additional information about Puerto Rico’s EITC parameters, see Javier Balmaceda, “Puerto Rico on Verge of Implementing an EITC,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 10, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/puerto-rico-on-verge-of-implementing-an-eitc.

State EITCs Are Easy to Administer, Offer Good Value to States

State EITCs are easy for states to administer and for working families to claim. States incur virtually no costs for determining eligibility for the credit because, in most cases, families eligible for the federal credit also are eligible for the state credit. Since state credits typically are set at a fixed percentage of the federal credit, state revenue departments need only add one line to a state’s income tax form, and filers need only multiply their federal EITC by a specified rate to determine their state credit.

State EITCs also offer a good value to states. In states with an income tax and a refundable EITC, the EITC costs less than 2 percent of state tax revenues each year.[11] Because state EITCs are well targeted to low- and moderate-income working families, they cost less than many other tax cuts that states consider.[12] A credit of a few hundred dollars can make a big difference to many families without making a major dent in a state’s treasury.

Also, if a state raises a tax that hits low-income households hardest, like the sales tax or gas tax, it can help make low-income families whole again by setting aside part of the resulting revenue to adopt or expand an EITC.

Box 4: Even States Without an Income Tax Could Offer a State EITC

Like the federal EITC, state EITCs have a long, successful history of using the income tax to improve the economic security of low-income working families. Some question whether a state without an income tax could offer similar assistance, since state revenue departments in these states do not typically collect the information about family income and structure needed to determine EITC eligibility. The example of Washington State’s Working Families Tax Rebate, however, illustrates how states without an income tax could work with the IRS to provide a state credit.

The Washington EITC has never taken effect because the state legislature hasn’t funded it,a but its design shows how it would work in the absence of a state income tax. To confirm eligibility, Washington State would use data on federal EITC claimants that the IRS provides to state revenue departments under a data-sharing arrangement. Piggybacking on these federal efforts saves administrative costs for the state. State officials estimate that when the credit was phased in fully, the administrative costs would constitute only about 4 percent of the cost of the EITC itself.b (Administrative costs in states that already have an income tax are substantially lower, typically well below 1 percent of the credit’s value.) If Washington were to increase the size of its credit, the administrative costs would be an even smaller share of the total cost.

Other states without a broad-based income tax (Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming) could follow the Washington State model. State EITCs could be particularly helpful in these states because their tax systems rely heavily on excise taxes, property taxes, and in most cases sales taxes. Because of this reliance, low- and moderate-income families in these states tend to pay a significantly higher share of their income in taxes than wealthier families.c

a The Washington State credit was scheduled to take effect in tax year 2009, but policymakers have not financed it, largely because of the Great Recession and resulting revenue shortfalls.

b Fiscal note for Washington ESSB 6809.

c ITEP, “Who Pays, 6th Edition,” https://itep.org/whopays/.

End Notes

[1] Puerto Rican families are not eligible for the federal EITC. The Puerto Rico EITC is a local tax credit that provides a maximum credit of between $300 and $2,000, depending on family size and configuration. It is available to working people on the island making less than about $34,000 (or $42,000 for a married couple), with the highest benefits provided to people with incomes between $6,000 and $18,000, depending on family size.

[2] David Neumark and Peter Shirley, “The Long-Run Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Women’s Earnings,” University of California-Irvine Economic Self-Sufficiency Policy Research Institute, December 18, 2017, https://www.esspri.uci.edu/files/docs/working_papers/ESSPRI%20working%20paper%2020175%20Neumark%20Shirley.pdf.

[3] Chuck Marr et al., “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” CBPP, updated October 1, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3793.

[4] According to Census’ Current Population Survey, 8 million poor children had at least one working parent in 2018.

[5] Molly Dahl et al., “The Earned Income Tax Credit and Expected Social Security Retirement Benefits Among Low-Income Women,” Congressional Budget Office, March 5, 2012, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/43033.

[6] Marr et al.

[7] Greg J. Duncan et al., “Early Childhood Poverty and Adult Attainment, Behavior, and Health,” Child Development, January/February 2010, pp. 306-325, and Jacob Bastian and Katherine Michelmore, “The Long-Term Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Children’s Education and Employment Outcomes,” December 27, 2016, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2674603.

[8] Other cuts include: Oklahoma cut its credit by nearly 70 percent in 2016, shrinking it to only cover state income tax liability. In 2013, North Carolina allowed its EITC to expire and cut it by 10 percent in its final year of existence. In 2011, Michigan cut its credit by 70 percent and Wisconsin cut its credit by 21 percent for families with two or more children. In 2010, New Jersey cut its credit to 20 percent of the federal EITC from 25 percent, though it has since raised the value of the credit.

[9] The 2009 Recovery Act included two key provisions to help the EITC go further. First, it expanded “marriage penalty relief” by raising the EITC income eligibility level for married workers by $2,000, thereby extending eligibility for the maximum credit to more married-couple working families with low incomes. Second, it provided, for the first time, a third benefit tier for larger families. Working families with three or more children receive an EITC equal to 45 cents for each dollar earned up to $14,290, for a maximum credit of $6,431 in 2018. The credit completely phases out for single-parent families with three or more children when their income exceeds $49,194 and for married-couple families of this size when their income exceeds $54,884. These expansions were extended in 2012 and made permanent at the end of 2015.

[10] California’s credit is worth up to 85 percent of the federal credit for workers earning up to $7,800, depending on family size. It is only available to workers earning up to about $30,000, also depending on family size. In 2019, the maximum credit ranges from $240 for workers without dependent children to about $3,000 for workers with three or more children, plus a new $1,000 Young Child Tax Credit for families with children under 6. The value of the state EITC is set each year by the legislature.

[11] Four factors affect the cost of a state EITC: the number of families that claim the federal credit, the percentage of the federal credit at which the state credit is set, whether the state credit is refundable, and how many state residents who receive the federal credit also claim the state credit.

[12] For further information about estimating the cost of a state EITC, see Erica Williams, “How Much Would a State Earned Income Tax Credit Cost in Fiscal Year 2020?” CBPP, updated March 7, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/how-much-would-a-state-earned-income-tax-credit-cost-in-fiscal-year.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise