So far in the current, pandemic-driven economic downturn, some states are following their playbook from the Great Recession of 2007-09 when they often closed large budget shortfalls with cuts to schools, higher education, and economic supports rather than protecting families and communities from the worst of the economic fallout. Those measures of roughly a decade ago ramped up layoffs that slowed the recovery, increased hardship, and worsened long-standing structural inequities that hold back Black, brown, and Indigenous people as well as women and workers struggling on low pay. In the coming year, states can take a different approach that raises the resources needed to stave off cuts, limits economic hardship, and advances equity-oriented, antiracist policies.

State economies and communities thrive when public investment in the foundations of broad prosperity unlocks the potential of every person and when structural barriers erected by racism and discrimination are knocked down. Good schools in every community offer children from lower-income families a chance at a better future. Family economic supports help parents provide their children with stable housing, nutritious food, and less stressful home lives. Health coverage protects families from bankruptcy due to a health emergency or chronic illness and ensures that businesses have healthy, productive workers. High-quality infrastructure — roads, bridges, ports, and waterways — helps businesses get their goods to market, and building it creates good jobs in the short term when the economy is not at full employment.

And, to ensure all communities thrive, states and localities must help undo the destructive legacies of past racism and the damage caused by continuing racial bias and discrimination. They can better design policies to address these harms and create more opportunities for people of color, which will make state economies more equitable and stronger, benefiting people of all backgrounds. They can also make their state a better place for people to live, work, and prosper regardless of their immigration status by enacting policies that take an inclusive approach to immigrants.

Forward-looking, antiracist, equitable tax policies and public investments are key to creating these conditions, but the Great Recession and many policies states adopted in its aftermath worsened longstanding inequities based on race, ethnicity, or income. Between 2005 and 2009, the period during which the housing bubble burst and the recession occurred, the median Black household lost more than half its meager wealth and the median Hispanic household lost two-thirds of its wealth.[1] Subsequent state actions that sharply increased college tuition, cut funding for schools, and weakened income supports like unemployment insurance and assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program added to the already extensive damage in Black and Latinx communities. And some states enacted policies that further constrained opportunities for immigrants. Further, some states cut taxes sharply for the wealthy and corporations, which primarily benefited white, affluent people, and some states and localities increased taxes and fees that fall hardest on those with the least ability to pay, which (along with cuts in public services) disproportionately harmed people of color.

These steps also made the Great Recession deeper and longer than it otherwise would have been and weakened our economy over the long term by neglecting basic investments in our children, our health, and the public systems that help people and businesses thrive. Now we’re trying to fight a pandemic when many public health agencies are under-resourced, unemployment systems are outdated, and teachers are underpaid.

To be sure, some states made progress in these areas in the years between the beginning of the Great Recession and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly three-quarters of the states expanded their Medicaid programs under the federal Affordable Care Act, and some states raised income taxes on the wealthy or corporations, strengthened earned income tax credits for families in poorly paid jobs, improved access to higher education for certain immigrants, or reformed criminal justice policies, among other things.

In the current downturn, states have already laid off or furloughed hundreds of thousands of workers and imposed harmful cuts, and some are proposing irresponsible income tax cuts including eliminating state income taxes.[2] But for most states the most consequential decisions will occur in the next few months as they hold their first full legislative sessions under COVID. To chart a better course, states can follow these three principles:

- Target aid to those most in need due to the COVID-19 and consequent economic crises. States’ immediate policy responses should prioritize supports for people and communities most in need due to the pandemic and accompanying economic crisis. They should target aid to essential workers and people who, due to lack of public investment, economic inequality, and historical and current discrimination and bias,[3] faced health and economic insecurity even before the pandemic. That includes people who have chronic health issues and people who are uninsured, experiencing homelessness, facing major barriers to work, or struggling on low pay, as well as immigrants who often have less access to supports.

- Adopt policies that address structural inequities. States can use this moment to address inequities due to historical racism and various forms of ongoing bias and discrimination. For example, they can make state unemployment rules more inclusive, boost income through state earned income tax credits, help tribal governments harmed by the pandemic, and eliminate criminal legal fees.

- Protect state finances to preserve the foundation of strong economies and widespread opportunity. Nearly every state’s tax system asks the least of the highest-income households, as a share of income. By raising taxes on high incomes and on various forms of wealth, much of which goes untaxed, states can build fairer tax systems while raising revenue for equity-enhancing public investments. States can also draw on their “rainy day” reserve funds, roll back ineffective corporate tax breaks, reform or repeal restrictions on revenue-raising by localities, and borrow (taking advantage of today’s low interest rates) for infrastructure projects that especially benefit neglected communities.

The Great Recession was the worst downturn for states in decades, causing state revenues to fall off a table and remain depressed for years. In the first five years after the recession hit, states closed over $600 billion in shortfalls, more than double the amount closed during the 2001 recession. (In the current crisis, CBPP’s latest forecast projects shortfalls for states, localities, tribal nations, and U.S. territories at $300 billion, net of federal aid to date, through fiscal 2022. Assuming states spend all of their rainy day funds still leaves about $225 billion in shortfalls. This estimate does not include extensive but difficult-to-measure costs to fight the virus, educate students effectively during a pandemic, and help people and businesses struggling due to the pandemic and its effects.[4])

To close their budget shortfalls during the Great Recession, states could have focused on policy approaches that protected families and communities from the worst of the economic fallout. Examples include drawing fully on reserve funds, raising new revenue (particularly from those who remained well off during the recession), cutting back on spending that worsens racial and class inequities (as is typically true of spending on incarceration and corporate tax breaks, for example), and borrowing prudently.[5] Instead, they primarily responded by laying off workers and cutting spending for schools, colleges, health programs, and other public services. Spending cuts accounted for nearly half of state actions to close their shortfalls between 2008 and 2012, three times as much as tax increases and five times as much as “rainy day” fund withdrawals.[6] Without the emergency federal aid provided through the 2009 Recovery Act, the cuts likely would have been even deeper, but that aid only covered about a quarter of state shortfalls. State cuts were so deep and harmful that in a sizeable share of states, services such as education and public health capacity remained diminished when the COVID-19 pandemic struck earlier this year, a dozen years after the Great Recession hit (see below).

In addition, states and localities began laying off workers in the summer of 2008, the start of the first state fiscal year during the recession, and continued layoffs for the next five years; by the summer of 2013, they had laid off nearly 750,000 people. These layoffs and other spending cuts deepened the recession and weakened the economy’s recovery. Over the first two years after the recession officially ended — June 2009 to June 2011 — the private sector added about 1.3 million jobs, but states and localities cut 450,000 jobs.

While the cuts made life harder for people across racial categories, people of color felt many of the most harmful effects. Due in part to historical racism and modern-day discrimination, people of color often have little wealth to draw on during hard times. And many live in neighborhoods where underinvestment has weakened schools and other public infrastructure and where over-policing and criminalization of Black and brown people leave them disproportionately likely to have been incarcerated or to have a family member incarcerated. Further, the recession hit communities of color especially hard by raising unemployment and erasing a large share of the housing equity that families had built. Between 2005 and 2009, the median Black household lost more than half its meager wealth, which fell from about $12,000 to less than $6,000, and the median Hispanic household lost two-thirds of its wealth, which fell from over $18,000 to about $6,000. The median white household’s wealth fell by about one-sixth, to about $113,000.[7]

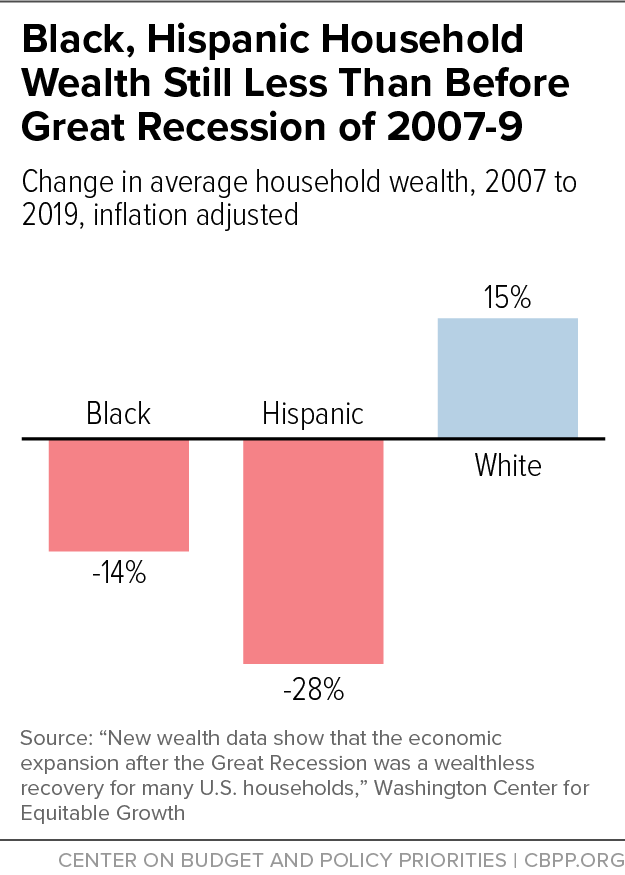

Average wealth is significantly higher than median wealth for all racial groups because wealth is very concentrated at the top,[8] but changes in average wealth also show stark racial disparities in the impact of the Great Recession. In 2019 — a full decade after the recession ended — the average Black household had about 14 percent less wealth than it did in 2007, while the average Hispanic household had about 28 percent less and the average white household had 15 percent more. (See Figure 1.)

Harsh state spending cuts and other damaging state and local policy choices in the aftermath of the downturn added to challenges facing households of color and immigrants, further widened racial and class inequities, and left the country less prepared to cope with the current, pandemic-driven downturn.

Investing in K-12 schools provides a crucial foundation for a strong future for all of us and is especially important for boosting opportunities for low-income children, immigrants, and children of color. But in response to the Great Recession and slow recovery, nearly all states reduced school funding, often deeply. By 2011, 17 states had cut per-student funding by more than 10 percent, after adjusting for inflation. Local school districts responded by cutting teachers, librarians, and other staff; scaling back counseling and other services; and even reducing the number of school days.

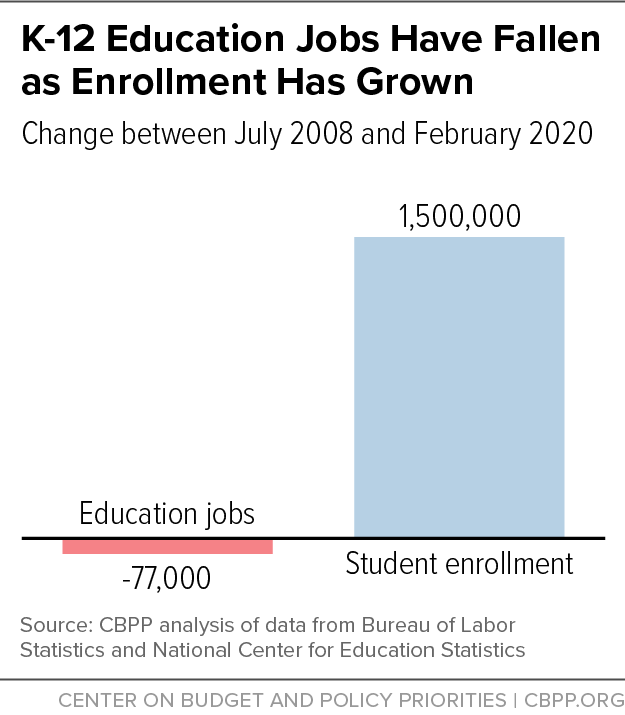

Many school districts have never recovered from those layoffs. When COVID-19 hit, K-12 schools nationally employed 77,000 fewer teachers and other workers even though they were teaching 1.5 million more children, and overall funding in many states was still below pre-Great Recession levels.[9] (See Figure 2.)

Underinvestment in education has left many schools understaffed. As of 2018, schools nationwide needed about another 110,000 qualified teachers, according to the best available estimate, likely due in part to low teacher pay.[10] Further, many teachers are not fully certified or lack educational background in the primary subject they teach, a problem that low teacher pay makes more difficult to overcome.[11]

Having qualified teachers in high-poverty schools is especially important for low-income students and students of color. However, teachers in high-poverty schools often have less experience, earn less on average than teachers in high-poverty schools,[12] and have higher turnover rates. They also often have less access to professional development and other supports. These disparities in teacher experience and longevity can exacerbate the disadvantages students in high-poverty schools face.

A strong and affordable system of higher education is crucial during downturns because it allows residents to increase their skills and broaden their prospects while the job market is weak. Regional universities and community colleges can play a particularly powerful role in boosting opportunities for immigrants and people from low-income families and communities of color. During the Great Recession and its aftermath, though, nearly every state sharply reduced funding for public higher education, by an average of 23 percent per student after adjusting for inflation.[13] As late as 2019, per-student funding was still down nearly 12 percent in the median state.[14]

Public colleges and universities, which receive over half of their funding from states, responded to these cuts by raising tuition significantly. As of the 2019 school year, annual published tuition at four-year public colleges was 35 percent above pre-recession levels, even after adjusting for inflation. In Louisiana, tuition nearly doubled, and in nine other states — Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Nevada, Tennessee, and West Virginia — it rose more than 50 percent, after adjusting for inflation.[15] These mammoth hikes have left many students and their families either saddled with debt or unable to afford college altogether. This is especially true for students of color (who have historically faced large barriers to attending college), low-income students, and students from non-traditional backgrounds. Higher costs jeopardize not only those students’ prospects but also the outlook for their communities and states, which increasingly depend on a highly educated workforce to thrive.

States steeply reduced public health funding after the Great Recession, a set of decisions whose imprudence is especially evident during the current pandemic. States and localities cut at least 38,000 public health jobs between 2008 and 2019, according to an analysis by Kaiser Health News and the Associated Press.[16] The analysis also found per capita spending has fallen by 16 percent for state health departments and 18 percent for local health departments since 2010. As a result, “hollowed-out state and local health departments were ill-equipped to step into the breach” when the pandemic arrived, the analysis found.

That weakened capacity has had deadly ramifications — particularly for people who are Black, Native American, Hispanic, or immigrants, who have been especially likely to be infected with and die from COVID.[17] These groups are more likely to work in low-wage, “essential” jobs that carry more risk of exposure to the virus,[18] to have underlying health conditions that make it harder to fend off the virus,[19] and to lack access to health coverage.[20]

Cuts in Unemployment Benefits and Other Income Supports

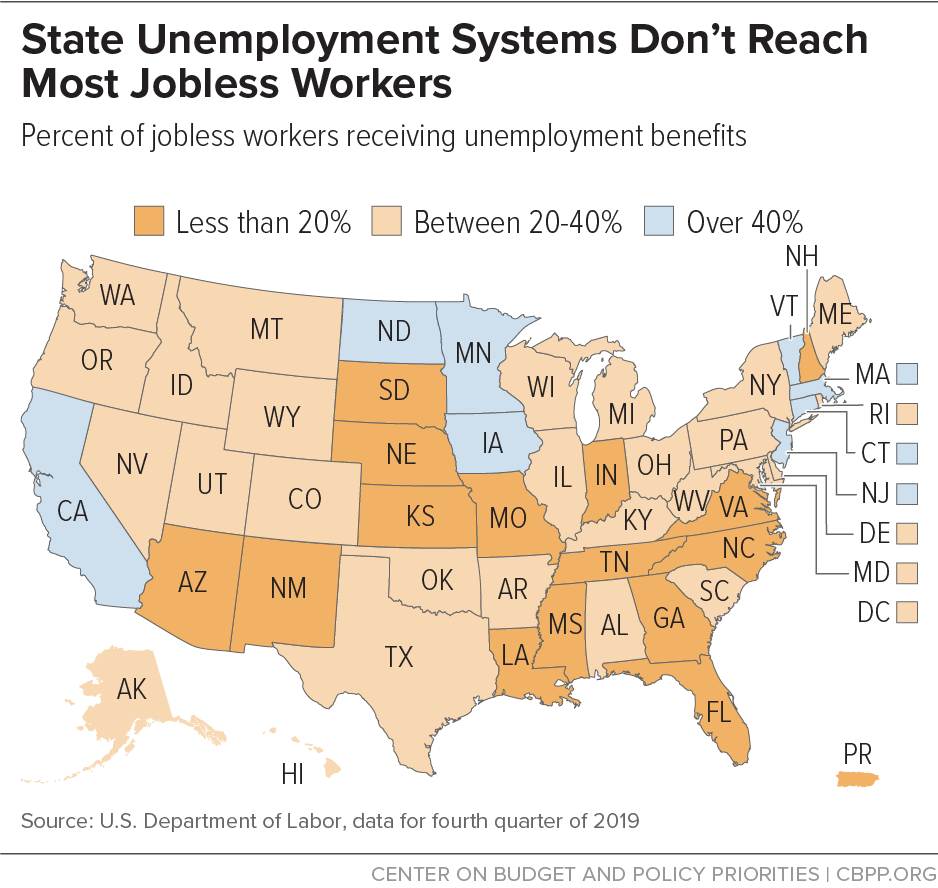

States’ unemployment insurance (UI) systems, built many decades ago for an economy in which far fewer workers were employed part time or as independent contractors, reach only a small share of jobless workers and often provide only meager benefits. This weakness partly reflects state cuts in UI benefits during and after the Great Recession, which diminished the system’s power and effectiveness heading into the current downturn. Just 29 percent of unemployed workers received UI at the end of 2019, compared to 36 percent at the end of 2007.[21] (See Figure 3.)

Some states also cut the length of time jobless workers may receive benefits. For decades before the Great Recession, all states allowed jobless workers to receive up to 26 weeks of benefits or more, but after the recession ten states broke with that custom. In Alabama and Arkansas, for example, workers currently can receive a maximum of 14 weeks and 16 weeks of regular UI benefits, respectively.[22]

Because states’ regular unemployment insurance systems are so weak, the federal government had to take bold action to protect jobless workers during the current crisis. In the spring of 2020, after the pandemic hit, federal policymakers created emergency unemployment benefit programs that temporarily increased benefits, expanded eligibility, and provided extra weeks of benefits. This emergency support has limited hardship among people laid off during the pandemic and boosted the economy by allowing them to sustain at least part of their consumption. But those measures are scheduled to expire in March, leaving many without any benefits and others with the far more limited state benefits, if policymakers do not extend these benefits.[23]

State cuts due to the Great Recession also weakened TANF, the country’s primary cash assistance program for poor families with children. During the Great Recession, temporary federal aid helped states address at least some of the increased need for assistance; the TANF caseload nationally grew a modest 10 percent between December 2006 and December 2010. But after the aid ended in 2010, several states cut benefits and reduced access to TANF,[24] which helped push caseloads well below pre-recession levels. In December 2019, TANF cases were about 43 percent lower than in December 2006.

Because of these and earlier state actions — and because the federal TANF block grant has not grown with inflation or need since the program’s inception 25 years ago — state TANF programs today do not adequately support those in poverty, particularly Black families. TANF’s direct cash assistance fails to lift a family of three with no other income to half of the poverty line (about $900 a month) in nearly every state. In addition, only 23 out of every 100 poor families with children nationwide received TANF in 2019 — down from 68 such families in 1996, when the program was established. Black children are likelier than white children to live in states where TANF’s benefits and reach are the lowest. For example, about 55 percent of Black children live in the 18 states where TANF benefits are below 20 percent of the poverty line, compared to 40 percent of white children.[25] Similarly, about 41 percent of Black children live in the 14 states where 10 or fewer families with children receive TANF for every 100 families living in poverty, compared to 28 percent of white children.

States and localities own about 90 percent of the country’s non-defense public infrastructure — its clean water systems, roads, bridges, transit systems, school buildings, and more.[26] How well they maintain and invest in these areas thus makes a crucial difference to the country’s quality of life and economic health.

Unfortunately, states and localities reduced spending on infrastructure as a share of the economy in the aftermath of the Great Recession, even as the economy recovered. State and local infrastructure spending as a share of gross domestic product is at its lowest point since the early 1980s, despite a clear need.[27] Across the United States, years of neglect have resulted in crumbling roads, bridges needing repair, inadequate public transport, outdated school buildings, and other critical infrastructure needs. In its most recent report card on the condition of America’s infrastructure, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave U.S. infrastructure a D+ or “poor” rating.[28]

Often, low-income communities and communities of color bear the brunt of this neglect. Starting in 2014, for example, thousands of people in the majority-Black city of Flint, Michigan were poisoned by lead after the city switched drinking water sources to save money.[29] In another example, a higher percentage of public schools in poor areas need repair than those in the wealthiest places,[30] partly because schools rely on local property taxes for funding and property values are lower in poor areas.

Tax Cuts Cemented Harm and Further Enriched Most Privileged

States that slashed spending during the Great Recession typically justified these policies by arguing that, with revenue down, they had no choice but to tighten their belts. But in the years after the recession, some states’ policy choices laid bare a different agenda, one aimed at cutting taxes, particularly on corporations and higher earners, at the expense of investment in public goods like education and infrastructure — and efforts to help families and communities hard hit by the Great Recession.

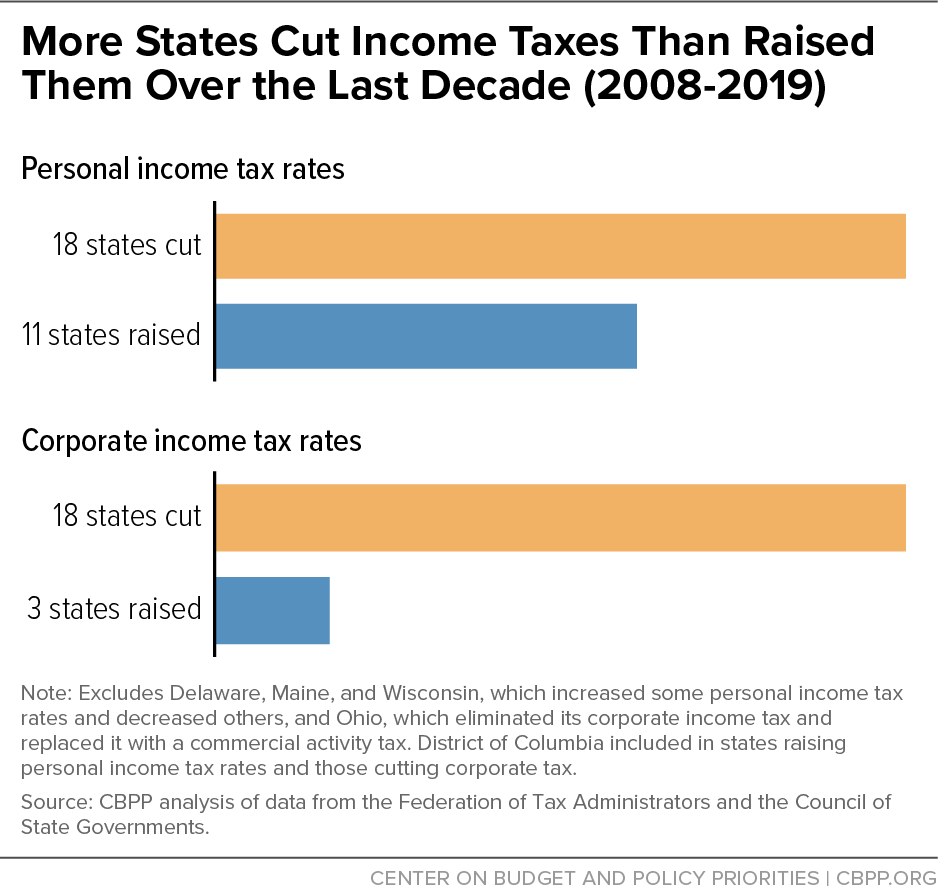

Between 2008 and 2019, 17 states plus the District of Columbia cut corporate income tax rates (see Figure 4) and others cut business taxes in other forms, sometimes by large amounts.[31] For example, Texas cut the rate of its business franchise tax, the state’s major business tax, by 25 percent, and Ohio replaced its corporate income tax and business personal property tax with a franchise tax that brings in roughly half the revenue.[32] Ohio also eliminated its estate tax. Since corporate stock is held overwhelmingly by wealthy, white households, corporate tax cuts added further to these households’ already substantial advantages.

In addition, 18 states cut personal income tax rates, all but two of which lowered the top rate.[33] Unlike the other two major sources of state and local revenue (sales and property taxes), income taxes are typically structured to ask more of the highest-income households than of middle- or low-income households. Therefore, cutting income tax rates typically reduces taxes the most — as a share of income as well as in dollar terms — for the highest-income households.

As a matter of economic policy, these tax cuts were failures. States that cut taxes received no evident economic benefit compared to neighboring states that did not cut taxes or even increased them; in a large share of cases, they fared worse.[34] The failure of tax cuts was predictable: given states’ balanced-budget requirements, they had to match every dollar of tax cuts with a dollar in reduced public-sector spending, often at the expense of investments in people and communities that improve long-term economic outcomes. Nor were tax cuts a response to any broad public outcry for lower taxes; poll after poll showed that majorities of state residents supported both fairer and more adequate tax systems to fund services.

Since these policies’ primary beneficiaries — people with large amounts of wealth and income —are overwhelmingly white and those facing hardship due to public service cuts and fee hikes are disproportionately people of color, these policy choices worsened the extreme racial inequities built up in the past through openly racist public policies and that remain in place today. In some cases, tax cut proponents drew directly on white supremacist tropes, as when economists Art Laffer and Stephen Moore called for states across “Dixie” to eliminate their income taxes.[35]

Some states and localities added to the harm by increasing taxes and fees that fall hardest on those with the least ability to pay, such as fees imposed on people caught up in a discriminatory system of law enforcement.[36] In the most widely known case, the U.S. Justice Department found that the criminal justice system in Ferguson, Missouri was heavily driven by revenue needs rather than public safety.[37] To support its budget, the city relied increasingly on fees and fines imposed disproportionately on low-income Black residents. Ferguson was not an outlier: research has found widespread use of fines and fees that can cause long-lasting harm for individuals — often poor people of color — trapped in a cycle of debt and criminal justice involvement.[38]

Some states have adopted policies in the years since the Great Recession that helped boost the recovery and pushed back against structural inequities. For example:

- Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia have expanded their Medicaid programs under the Affordable Care Act, providing health care to millions of low-income people who previously could not afford it.[39] In several states, voters have taken the initiative to pass Medicaid expansion through the ballot.

- Eight states (California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon) and the District of Columbia increased income tax rates on high incomes.[40]

- Seven states adopted a new state earned income tax credit (EITC), which targets low-income working families. In addition, most of the states with existing EITCs improved them.[41]

- More than half the states reformed their criminal justice policies, such as by eliminating mandatory minimum sentences or reclassifying certain felonies as misdemeanors.[42]

- At least 14 states made higher education more affordable to immigrant students, such as by extending in-state tuition rates and financial aid regardless of immigration status.

- Some states improved school finance formulas to get more funding to high-poverty schools. For example, California adopted a new funding formula in 2013 that boosted districts’ aid for each student from a low-income family and each student learning English.

These forward-looking policy gains, many of which were adopted years after the Great Recession officially ended in 2009, improved the lives of millions of people. But their benefits were countered by the harmful policy choices mentioned above, which diminished the capacity of many states to respond effectively when the pandemic hit and the economy slowed.

As states hold their regular 2021 legislative sessions, they can adopt a more productive policy approach than they did in response to the Great Recession, taking on structural inequities even while addressing near-term fiscal challenges.

So far, they haven’t done particularly well. Since the pandemic hit, states and localities have laid off or furloughed 1.3 million workers and some have cut spending sharply in other ways. Leading policymakers in several states have proposed deep tax cuts, including eliminating the income tax.[43] But most states have avoided deep cuts other than layoffs so far, largely by operating temporarily under budgets they know are not balanced, using federal aid, and drawing down reserves; and Arizona and New Jersey have raised tax rates on high incomes. For most states, the next few months will be crucial in determining their policy response and the well-being of their residents for years to come.

Three principles should guide state policymakers in the months ahead:

Immigrants and Black, Native American, and Hispanic people are more likely to have experienced job and income losses and to be facing economic hardship.[44] As noted earlier, they are also more likely to work in low-wage, “essential” jobs that require them to interact regularly with people outside their homes, putting their health in danger during a pandemic. And, they are more likely to live in crowded conditions and to lack access to health care. Largely for these reasons, all of which are deeply shaped by historical racism and ongoing discrimination, COVID infection and death rates are higher among these groups. Immigrants without a documented status are ineligible for most forms of assistance, and immigrants who are eligible for health or food assistance often forgo it out of fear that receiving assistance will run afoul of the Trump Administration’s “public charge” rule and jeopardize their ability to remain in the United States.[45]

States’ immediate policy responses should prioritize supports for people and communities most in need due to the pandemic and accompanying economic crisis. They should target aid to people who, due to a lack of public investment, economic inequality, and historical and current discrimination and bias,[46] faced health and economic insecurity even before the pandemic. That includes people who have chronic health issues or are uninsured, undocumented, experiencing homelessness, facing major barriers to work, or struggling on low pay.

For example, the 12 states that have yet to take up the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion should do so now to ensure millions of people have health coverage during the COVID-19 crisis and its aftermath.[47] States also can provide emergency Medicaid for immigrants without documented status who have COVID-19-related health conditions. And states can go further by implementing state-funded health programs to provide health coverage to people ineligible for Medicaid, like certain immigrants. Making health coverage accessible to as many residents as possible is crucial to keeping people healthy and safe and containing the spread of the virus.

Other examples of constructive state policies include:[48]

- Providing rental assistance and other help for people experiencing homelessness or facing eviction, especially families with children and those facing bigger barriers such as people leaving jail or prison, people with substance use disorders, people with physical disabilities or mental health conditions, and immigrant families not eligible for other rental assistance.

- Expanding cash assistance through TANF;

- Providing emergency Medicaid for undocumented immigrants who have COVID-19-related health conditions or, preferably, implementing state-funded health programs to provide health coverage to people ineligible for Medicaid, like certain immigrants.

- Establishing emergency child care services for essential workers;

- Protecting funding for schools and students most in need;

- Releasing youth with low-level offenses or technical probation violations from confinement and supporting their re-entry into schools and communities while social distancing; and

- Requiring and funding COVID-19 data tracking to understand its disparate impacts.

As discussed below, even states facing revenue shortfalls can make these kinds of investments if they are willing to raise taxes on those who remain well-off despite the downturn. This would not only provide much-needed revenue for investments but also help the economy, by shifting resources from people who have substantial savings and who do not necessarily spend every dollar they receive in a year to people who are facing challenges affording the basics, who are likely to spend additional funds they receive. Shifting resources to those who will spend them boosts overall consumer spending and the economy overall.

Even as states respond to the immediate crisis, they can pursue policies that help undo longstanding structural inequities in the economy and society generally. States can do this by eliminating or reforming policies that directly worsen racial and economic inequities and by adopting new policies that advance equity.

Potential steps include:[49]

- Eliminating criminal legal fees and basing fines on ability to pay, thereby avoiding jailing people for being poor;

- Making UI systems more inclusive of part-time, contingent, and low-paid workers, who are more likely to be women and people of color;

- Considering ways to assist immigrants who are undocumented and who have been laid off due to the virus but are ineligible for existing federal and state benefits;

- Adopting paid leave policies that extend to low-income workers the degree of flexibility more often enjoyed by those in higher-paying jobs;

- Boosting income for workers in low-paying jobs through state EITCs and making state EITCs more inclusive of families with undocumented workers;

- Investing in schools in high-poverty areas still affected by the legacy of historic segregation and ongoing forms of disinvestment and discrimination;

- Investing in higher education for low-income students and students of color, including by prioritizing need-based aid over merit-based, and by prioritizing community colleges and regional universities in funding decisions; and

- Helping tribal governments harmed by the pandemic and, over a much longer period of time, by federal neglect.

Protect State Finances and Build More Equitable Tax Systems

The health and adequacy of state finances are critical to addressing the dire needs of those hit hardest by the crisis and dismantling longstanding racial and economic inequality, but state budgets face severe pressure from the COVID-19 outbreak and economic fallout. States can protect their finances to preserve the foundation of strong economies and widespread opportunity by, for example:

- Drawing on “rainy day” funds and other reserves as much as necessary to avoid cuts. States can help stave off deep cuts and minimize public-sector job losses by drawing on their reserves. With COVID-19 vaccines already being distributed and the possibility of more federal aid coming, states can limit hardship and boost the economy by spending their reserves without undo worry about needing substantial reserves in the future. Spending reserves to protect against public-sector layoffs can also enhance equity, since people of color make up a disproportionate share of the public workforce. Rainy day funds were designed to minimize cuts to services in adverse economic times, and while states generally do put these funds to use, they don’t always draw them down as much as they should when the economy turns down. In some cases, this is due to short-sighted limitations on using the funds or requirements to replenish them when the economy is still weak from a prior recession. States should act quickly to reform these policies.

- Raising revenue, especially from profitable corporations and the wealthy. As noted, past policy decisions have produced state and local tax systems that — in the vast majority of cases[50] — ask the least as a share of income of wealthy, mostly white households, thereby expanding wealth and income disparities often built or aggravated by racism. States have a choice during downturns: cut services, often in ways that harm families most in need, or raise revenue. That choice has important implications for racial justice, given that high-income and high-wealth households are disproportionately white and households with low incomes are disproportionately comprised of Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people, as well as immigrants. Moreover, tax increases are a particularly good option for states needing to close budget shortfalls in bad economic times — especially when those measures target the wealthy, who reduce their consumption less during economic downturns than less-affluent people do. In this particular downturn, with the stock market having risen significantly and high-income workers largely avoiding layoffs, tax systems based more on ability to pay are performing particularly well, limiting revenue losses in those states. States also should eliminate procedural barriers to raising revenue such as supermajority vote requirements, which have racist roots[51] and allow a small group of lawmakers to slow or block tax measures even when they have majority support.[52]

- Rolling back economic development incentives and other tax breaks for profitable corporations. Economic development incentives cost states about $45 billion per year, in aggregate, despite evidence that they are largely ineffective. Other tax breaks often reward companies for doing things they would have done anyway (such as locating in a certain place) or have a low “bang for the buck.” Rolling back ineffective breaks and using the savings to improve economic supports for people in hard-hit communities of color would also improve racial equity, since the corporations that most benefit from these breaks typically are owned mostly by white, wealthy shareholders.[53]

- Reforming or repealing restrictions on localities’ revenue-raising. The pandemic is sharply increasing costs and reducing revenue for localities as well as states, making it much harder for them to provide basic community services like schools, parks, and clean water. States can remove unnecessarily strict barriers to raising revenue at the local level. One such barrier is property tax limitations, which expand racial income gaps by disproportionately benefiting white homeowners, who are more likely than Black or Latinx people to own more valuable homes — in part because past government policies segregated people of color in lower-value areas.[54]

- Borrowing for equity-enhancing infrastructure investments. States can take advantage of today’s low interest rates and low state debt levels by borrowing for infrastructure projects aimed particularly at the hardest-hit communities. Projects could include improved public transit; modernized systems for clean drinking water; new, energy-efficient schools; and a range of projects to develop more sustainable energy supplies and mitigate damage from climate change. These projects both help bolster the long-term economies of communities and provide important near-term jobs for workers on the projects.