The health and economic burdens associated with the COVID-19 pandemic are falling disproportionately on people of color as well as on families and individuals with very low incomes, who faced significant economic and health challenges prior to the pandemic. Some communities of color are at higher risk of contracting the virus or developing serious complications from COVID-19, according to early data. And the most recent economic forecast by the Congressional Budget Office indicates that unemployment may remain high for a long time — well into 2022 — which, history shows, may negatively impact people of color and people with the lowest incomes disproportionately. Given this, the next major economic relief package should include relief measures that will help these households avert serious hardships such as eviction, homelessness, and food insecurity.

While comprehensive data on who has lost jobs and income are not yet available, early information is sobering. More than half of adults in lower-income households and 44 percent of Black and 61 percent of Hispanic adults say they or someone in their household has lost a job or taken a pay cut due to COVID-19, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.[1] Lost jobs, reduced pay, or illness all may exacerbate economic instability for people with limited resources, whose incomes often fell short of allowing them to make ends meet before the crisis or to save for a rainy day.

There is an urgent need to increase funds for housing, food, health, and income assistance to individuals and families that tend to experience the worst health, housing, and employment outcomes, and now may be facing new barriers to seeking and receiving help. People of color are disproportionately represented in this group of families, and racism and discrimination have created barriers to good health and economic outcomes that COVID-19 has exacerbated. People who were unemployed before the pandemic, families with high housing costs compared to their incomes, individuals experiencing homelessness, immigrants who face unique barriers to accessing assistance, and those returning from prison or jail are also at especially high risk of being unable to meet their basic needs.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and, to a lesser degree, other federal relief legislation include important provisions to help families and individuals who have lost their jobs weather the crisis. They fall short, however, in providing sufficient assistance directly to families and individuals who are at the highest risk of poor outcomes due to the health and economic crisis and have the least resources to deal with decreases in income and increased costs for utilities, food, and transportation brought on by the pandemic. Moreover, economic projections indicate that the need for relief is far greater and likely will last much longer than policymakers have provided for in legislation enacted so far.

As federal policymakers consider their next major response package, they should prioritize policies that would lessen the burdens that families with very low incomes and communities of color are facing, including:

- Increasing rental assistance. The package should provide housing agencies with at least 500,000 new Housing Choice Vouchers to help people with the fewest resources remain housed during the health crisis and economic recession. These vouchers would help families exit homelessness, protect themselves from violent family members, or leave doubled-up or overcrowded housing settings. They could also be targeted to help those who are being temporarily housed in hotels, motels, and other settings access housing once the immediate public health crisis ends.

- Providing more funding for emergency homelessness assistance. People experiencing homelessness are particularly at risk for the most harmful consequences of COVID-19 and the economic crisis. HUD’s Emergency Solutions Grant program needs additional resources to:

- Strengthen homeless service agencies so they can modify emergency shelters and temporarily house people in hotels, motels, and other settings that allow for social distancing, and

- Provide people who have lost income with short-term rental assistance so they don’t become homeless.

- Creating a flexible emergency assistance fund of at least $10 billion that states could use to provide monthly cash payments, emergency assistance grants, or subsidized jobs (when it is safe to do so) to families and individuals with the lowest incomes who are facing a crisis that could lead to eviction or result in serious health consequences. The fund would be targeted to families and individuals who are largely or entirely left out of other relief mechanisms or whose needs can’t be met with those measures alone. The fund would build on the lessons learned from the highly successful, bipartisan Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Emergency Fund during the Great Recession, which provided income to more than a quarter of a million families to help pay their rent and utilities, put food on the table, and cover the costs of other basic needs like diapers and personal hygiene supplies, while also supporting subsidized jobs.

- Increasing nutrition assistance. A 15 percent increase in the SNAP maximum benefit level would provide all SNAP households, including those with the lowest incomes, additional resources to purchase food. This would amount to an increase of approximately $25 per person per month, or just under $100 per month in food assistance for a family of four. SNAP benefits provide a critical resource to households that don’t have enough to make ends meet, but SNAP benefits fall short of meeting a typical family’s food need. During downturns, when people face longer periods of joblessness and reduced income, low benefits are particularly problematic. Additional funding for Puerto Rico’s Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP) is also needed to enable the Commonwealth to better meet rising need and to raise its low benefit levels. When households receive more food assistance through SNAP or NAP, some of their limited cash resources often are freed up to meet other basic needs, including paying their rent and utilities and buying personal care and cleaning supplies.

- Extending assistance to immigrants. Immigrants, including those who have lost jobs and those who are still in jobs that make them at heightened risk for contracting COVID-19, should not be left out of provisions that could help them put food on the table, pay their rent, and meet their health care needs. They also should not be coerced by the new “public charge” federal regulation to forgo assistance for which they are eligible out of a fear that receiving help during this crisis could hurt their ability (or the ability of family members) to remain in the United States with their families. The next package should reverse policies that keep certain immigrant families from receiving stimulus payments and undo, or at least suspend, the Administration’s harmful public charge rule.

States and localities as well as territories and tribes have received some emergency fiscal relief, but far too little to enable them to respond to the immediate public health emergency, absorb increased program costs, and avoid sharp spending cuts that would deepen and prolong a recession. Without robust fiscal relief, states, localities, territories, and tribes are likely to make cuts in education, health care, transportation, and assistance to those who are struggling that will disproportionately impact people of color, people with limited resources, and neglected neighborhoods. Providing robust, well-designed fiscal relief in the next package is a critical component to ensuring that the current health and economic crisis does not result in deep hardships for disadvantaged individuals, families, and communities.

Past policy decisions and lack of investment in communities of color have created disparities that put people of color at higher risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19, losing their jobs, and being unable to make ends meet during the sharp economic downturn caused by the pandemic.

Health disparities. Disproportionately Black counties have five times — and disproportionately Hispanic counties have three times — as many confirmed COVID-19 cases per capita as disproportionately white counties, according to a recent analysis.[2] Early state and local data also show that Black and Hispanic people are dying of complications from COVID-19 at higher rates than white people.[3] The Indian Health Service also reports concerns due to lack of testing and a recent outbreak within the Navajo Nation.[4]

Experts agree that COVID-19 is particularly harmful for people with underlying health conditions like lung disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Obesity and smoking are also risk factors for the worst COVID-19 health outcomes. Black people and American Indian/Native Alaskans experience chronic health conditions more often than white people.[5] Both populations have higher rates of heart disease, lung disease and asthma, diabetes, kidney and liver disease, and immuno-compromising diseases — putting them at higher risk of becoming seriously ill with COVID-19 and at higher risk of dying if they do contract the virus. Hispanic people face high rates of diabetes, asthma, and obesity, which put individuals at high risk of COVID-19 complications.[6] With high rates of diabetes, coronary heart disease, and obesity, adults living in Puerto Rico are also at high risk of COVID-19 complications.[7]

These health disparities exist because too often, people of color have experienced years of economic hardship, receive lesser quality health care, and have been segregated into neighborhoods that lack access to nutritious food, green space for exercise, clean air, and jobs that pay enough for people to have the money or time for recreational activities people at higher incomes enjoy, such as belonging to a gym.[8]

Employment disparities. The pandemic is also significantly affecting finances for many people of color due to employment disparities that pre-dated the crisis. People of color, including those who are immigrants, are disproportionately represented in lower-paying service industry jobs, including retail, hospitality, child care, and restaurants, that have been hard hit due to social distance restrictions. Some 24 percent of both Black and Hispanic people are in service industry jobs, compared to 16 percent of white people.[9]

Puerto Rico and tribal communities in the United States also are being hard hit by the economic consequences of the pandemic.[10] Tourism comprises an important part of Puerto Rico’s economy and for some tribes, casinos provide a significant source of both jobs and revenue. Both industries have come to nearly a complete halt during the pandemic, causing significant job losses and the loss of a key revenue source for their communities.

A recent Pew Research Center survey found that 61 percent of Hispanic adults reported they or someone in their household has lost a job or taken a pay cut due to COVID-19, compared to 44 percent and 38 percent of Black and white adults, respectively.[11] When the government survey data on those who lost jobs in March and April come out, many expect the job losses to be far larger among lower-paid jobs and, thus, to disproportionately fall on people of color.

Among those who remain employed, workers of color appear to be disproportionately employed in many jobs that require them to report to a job site rather than to work from home. This includes people who work in grocery stores, at warehouses, in product delivery, and in parts of the health care industry. These workers are at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 because they are unable to shelter in place at home, putting them at higher risk of coming into contact with people with the coronavirus.[12] This is also true for immigrants, many of whom are people of color — both those who have authorization to work in the United States and those without work authorization who nonetheless do jobs that are critical to our communities and economy.[13]

Some economists predict that, coming out of the crisis, the unemployment rate among Black workers could be as much as double the national rate.[14] If past experience holds, this gap will be worst for Black people with a high school degree or less where, even in good economic times, their unemployment rate is nearly double their white counterparts with the same education. Almost 15 percent of Black people without a high school degree were unemployed in 2019, compared to 8.3 percent of white people. For those with a high school degree but no post-secondary degree, 8.3 percent of Black people were unemployed, compared to 3.9 percent of white people.

Unemployment also is traditionally higher for Hispanic people than white people. In 2019, the unemployment rate for Hispanic people was about 5 percent; it was less than 4 percent for white people. The unemployment rate for Puerto Rico was 8.2 percent.

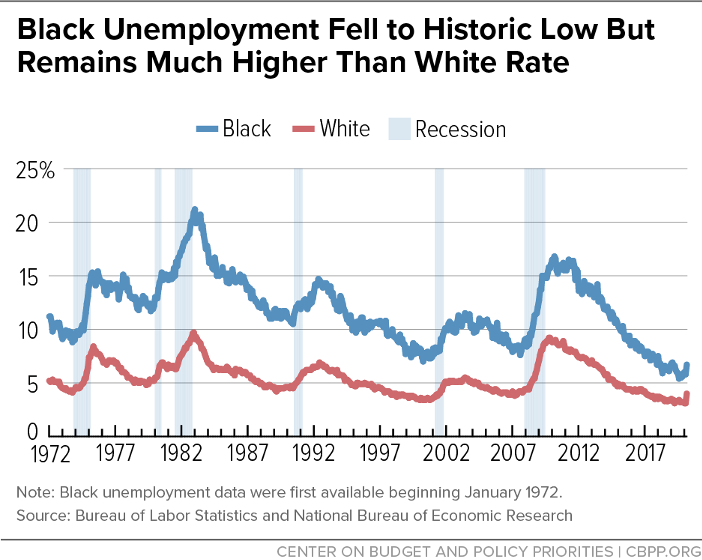

The effects of the economic fallout could be long-lasting. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the national unemployment rate will still be 9.5 percent at the end of 2021, up from 3.5 percent before the crisis hit.[15] As Figure 1 shows, the gap between Black and white unemployment rates tends to be widest when unemployment is high.[16] The gap does not narrow until unemployment has fallen substantially, but even when the gap narrows, the disparity remains. It was not until several years after the Great Recession that the unemployment rate for Black people returned to its pre-recession rate, and it remained well above the rate for white people thereafter. [17]

The longer the crisis lasts, the harder it will become for people to meet their basic needs, and Black and Hispanic people will be hit the hardest. Just 27 percent of Black, 29 percent of Hispanic, and 53 percent of white adults have emergency funds that would last three months, an April 2020 Pew Research Center survey found. Moreover, 48 percent of Black, 44 percent of Hispanic, and 26 percent of white adults said they wouldn’t be able to pay all of their bills in April.[18] The longer people are unable to pay their bills, the harder it will be for them to catch up and their risks of hunger, eviction, and homelessness will likely increase.

The pandemic has worsened conditions for families that were already struggling to pay their rent and put food on the table and may have significant difficulty weathering the crisis on their own. But the pandemic has created new barriers to seeking and receiving help, with family and friends who might have helped before the pandemic facing their own struggles and some social service organizations moving to online operations, narrowing the services they provide, or even closing their doors. In the Pew Research Center survey, only 16 percent of lower-income adults who didn’t have emergency funds that would last three months said they could cover their expenses for three months by borrowing from friends or family, using savings, or selling assets.[19]

The following groups of individuals and families will face particularly difficult challenges during the crisis:

Individuals who were unemployed before the pandemic. Although unemployment was at a historic low prior to the start of the pandemic, almost 6 million working-age adults were out of work and looking for jobs in February 2020.[20] About two-thirds were not receiving unemployment insurance and are very unlikely to be eligible for the expanded unemployment insurance benefits provided through the CARES Act because they did not lose their jobs for a COVID-19 reason. Prior to the crisis, individuals who were out of work — they may have been between jobs, have lost a job due to illness or the need to care for a family member, or have temporarily left the labor market for any number of personal circumstances — often could find a job relatively quickly, albeit often a low-paying one. Many of these individuals will now face far longer periods of joblessness than they likely were expecting.

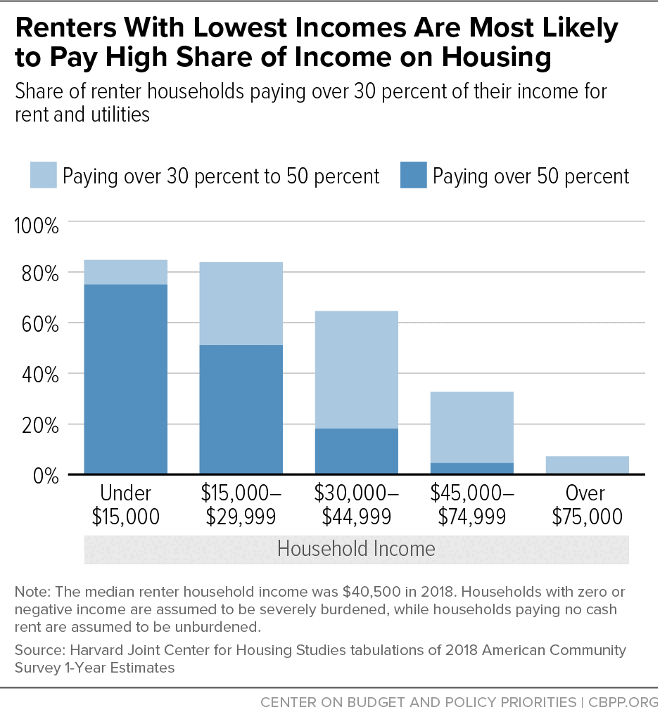

Families with high housing burdens. Before the pandemic, about 75 percent of renter households with annual incomes of less than $15,000 paid over half their income for housing. Of those earning between $15,000 and $29,000, 50 percent paid over half their income for housing (see Figure 2). Children make up about one-third of the people in low-income renter households paying over 50 percent of their income on rent.[21]

When families spend so much of their income on rent, it’s harder for them to save, which makes it nearly impossible to meet their basic needs if they lose a job, their income falls, or costs for those basic needs rise. Without assistance, some could lose their homes and be compelled to live with other family members or friends, in shelters, or on the streets. Before the crisis, 3 out of 4 households that were likely eligible for federal rental assistance didn’t receive it due to scarcity of funding.[22] The need for housing assistance will grow during this economic downturn, as it did during the Great Recession.[23]

People experiencing homelessness. People without a place to call home are among those struggling the most now. On any given night, prior to the pandemic, over 500,000 people were experiencing homelessness. Many are at risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 because they have pre-existing chronic health conditions or are older adults. Our typical response to homelessness is large, densely populated shelters, which make it difficult to adhere to social distancing guidance and other methods of protecting oneself from the virus.

Individuals returning from jail or prison. In recent years, state and federal prisons have released about 600,000 individuals per year, or about 50,000 each month.[24] An even larger number are released from jails.[25] In response to concerns about the spread of COVID-19 in jails and prisons, some individuals are being released early. An estimated 40 percent of people who are incarcerated report having chronic health conditions that could put them at higher risk of contracting and serious complications from COVID-19 both while in jail or prison and upon release.[26]

Even in good economic times, this population experiences obstacles to work, housing, medical treatment, and financial security upon release from incarceration. Now, the health and economic crisis will make it difficult for many people leaving incarceration to successfully re-enter society and be self-sufficient. Without income to meet their basic needs, some will likely become homeless and others will likely double up with family members, stretching tight family budgets and making it difficult to adhere to social distancing recommendations. Over the long term, these conditions put them at risk of re-incarceration.

Immigrants. The health and economic consequences of the pandemic will hit immigrants hard. The Migration Policy Institute estimates 6 million foreign-born workers are employed in industries vital to the COVID-19 response (which puts them at higher risk of being exposed to the virus) and another 6 million work in some of the industries hardest hit by job losses in the fight against COVID-19.[27]

Immigrants and their families are less likely to have access to government health, nutrition, and income support, either because their immigration status makes them ineligible for supports or they forgo assistance due to fears that receiving help will jeopardize their immigration status — or that of a family member — in the future. Forgoing testing and health and nutrition assistance could put immigrants at high risk for negative health outcomes and financial insecurity. When immigrants lose their jobs, they often have more limited options for getting help to meet their basic needs.

Expanding housing assistance, investing in programs that provide ongoing or emergency cash assistance to help families meet their basic needs, and increasing SNAP benefits are effective and efficient ways to help people with low incomes and limited savings make ends meet. Policymakers should pursue key policies in these areas in the next major economic response package.

The CARES Act boosted funding for the Community Development Block Grant, the Emergency Solutions Grant, and other HUD-funded rental assistance programs. Those funds will help reduce evictions of low-income renters, help communities reconfigure their homeless assistance systems to mitigate COVID-19-related health risks, and help more people move from homelessness into healthy housing, though this housing is often only temporary. And for those currently in federally backed housing, the CARES Act temporarily halts evictions. This provision, along with state and local eviction moratoriums and utility shut-off bans, is important but does not keep people from accumulating rent- or utility-related debt that they will struggle to pay back. And the rental assistance included in CARES is short-term assistance that could end before a family can afford housing without it. As the crisis worsens, more is needed to help those experiencing homelessness, to prevent homelessness, and to provide housing stability.

Emergency housing vouchers are needed to provide housing stability during the health and economic crisis and as we recover.[28] The federal government should fund at least 500,000 new Housing Choice Vouchers — which help families afford decent, stable housing in the private market — to help families exit homelessness or temporary housing settings, protect themselves from violent family members, or leave doubled-up or overcrowded housing settings.

Another concern is how to help those who are being temporarily housed in hotels, motels, and other settings once the immediate public health crisis ends. The response should not be to evict people back onto the streets or into shelters, but it is unlikely that many will quickly find a job that pays enough for them to afford housing. To rent the average two-bedroom apartment without spending more than 30 percent of its income on housing, a family must earn $47,754 annually, experts estimate.[29] Rigorous research shows that housing vouchers are the single most effective policy for reducing homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding among extremely low-income people.[30] Housing agencies already know how to help households with low incomes locate and secure housing and the programs, while under-funded, help a large number of households of color.[31]

Expand Funding for Homeless Services

Homeless service agencies, states, and localities need significantly more funding to address the needs of people experiencing homelessness during this crisis. Experts estimated in March that homeless shelters and transitional housing providers needed at least $11.5 billion to properly serve clients;[32] the CARES Act included $4 billion. In addition, more resources are needed for short-term rental assistance to help people stay in their housing and avoid homelessness. The federal government should provide substantially more funding in the Emergency Solutions Grant program to address both needs.

Additional resources would help homelessness service providers adjust their locations to make adhering to social distancing guidance possible, serve people with complex needs such as those with behavioral health conditions or exiting jails and prisons, and provide short-term assistance to prevent homelessness. These funds are also a way to target resources to people of color at high risk during the health and economic crisis. According to the most recent data, each race/ethnic group of color measured was over-represented among the homeless population, with Black people being the highest at 40 percent.

Although the CARES Act authorizes substantial cash benefits that will help large numbers of people, some of the families and individuals with the fewest resources won’t benefit from them. Individuals who were looking for work but unemployed or unable to work before the pandemic hit will not be eligible for expanded unemployment benefits. And, although many of the families and individuals with the lowest incomes are eligible for the Act’s economic impact payments, they may not receive them in time to avert a crisis and, indeed, may be left out if they aren’t able to fill out the online form the IRS has established for those who do not file a tax return to apply for the payment.

States will need additional, flexible resources to provide basic income assistance and emergency aid in the short term and subsidized employment over the long term to individuals and families with the fewest resources that lack access to other forms of significant and ongoing support. Currently, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program funds can be used to help families with children meet their basic needs, but the block grant has lost about 40 percent of its value since it was created in 1996, only a few states have substantial unspent funds that could be tapped to provide additional assistance, and it cannot generally be used for adults who aren’t caring for or financially responsible for children.

The few states that have used their TANF funds to help people avoid crises or to meet critical needs have shown how great the need is. For example, Tennessee received 22,000 applications for emergency assistance in the first week after it began accepting applications. And two Ohio counties drained the more than $1 million they set aside to provide emergency assistance grants within 48 hours.[33]

A flexible emergency fund that builds off of the successful experience and lessons learned from the TANF Emergency Fund, which was available to states during the Great Recession, could help to avert the crises that accompany extreme hardship.[34] With a $10 billion fund (and more funding if unemployment remains higher for more than the next 12 months), states could provide three types of assistance to help families and individuals meet their basic needs: (1) one-time emergency assistance payments to help families buy essential supplies or pay for rent or utilities; (2) monthly cash payments to help families with no other income meet their basic needs; and (3) subsidized employment, if unemployment remains high after it is safe to return to work.

To ensure the majority of the funds go to families and individuals with the fewest resources, the funds should be targeted to families and single individuals with incomes below 100 percent, or no more than 200 percent, of the federal poverty line. Families with children and adults who aren’t supporting children should be eligible to receive assistance. The fund should also be structured to ensure that Puerto Rico, other territories, and tribal governments also receive funding that reflects the need among their populations.

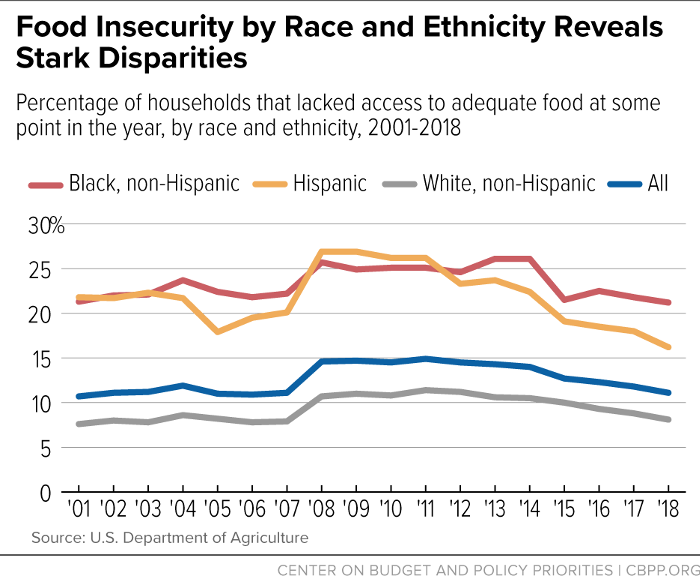

Rates of food insecurity by race and ethnicity reveal stark disparities (see Figure 3). In 2018, 21.2 percent of Black, non-Hispanic households and 16.2 percent of Hispanic households lacked access to adequate food at some point during the year, compared to 8.1 percent of white households.[35] The disparate impacts of COVID-19 on communities of color could cause these disparities to widen further.

The food assistance provisions of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act are providing additional SNAP benefits to many households. But the primary benefit increase, emergency allotments that raise all households’ benefits to the program’s maximum allotment, will only last during the public health emergency and leaves out nearly 40 percent of SNAP households — those with the lowest incomes, who have the most difficulty affording adequate food. Some 5 million children are among those now left out. In the next relief package, policymakers should provide additional food assistance to households with the lowest incomes by increasing the SNAP maximum benefit and increasing funding for Puerto Rico’s Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP).

SNAP is one of the few means-tested government benefit programs available to almost all households with low incomes; SNAP reaches low-wage working families, seniors, people with disabilities, and other households with low incomes and targets benefits to those with the lowest incomes. Prior to the economic downturn, SNAP provided food assistance to nearly 40 million people in nearly 20 million households. More than two-thirds of SNAP participants are in families with children; a third are in households with seniors or people with disabilities. And, during the current crisis, eligibility restrictions that limit access to SNAP for adults under the age of 50 without children in the household are not in effect, which broadens the program’s reach.[36]

SNAP benefits provide a critical resource to households that don’t have enough to make ends meet, but they fall short of meeting a typical family’s food need. When households receive more food assistance, it can free up some of their limited resources to meet other basic needs, including paying their rent and utilities and buying personal care and cleaning supplies.

A 15 percent increase in the SNAP maximum benefit level (known as the Thrifty Food Plan) would provide all SNAP households, including those with the lowest incomes, additional resources to purchase food. This would amount to an increase of approximately $25 per person per month, or just under $100 per month in food assistance for a family of four.[37] The 15 percent increase in SNAP benefits should remain in place until economic measures show that unemployment is no longer significantly elevated.

SNAP has proven to be one of the most effective mechanisms available to reach low-income households and a SNAP benefit increase can be implemented virtually immediately. States will, however, need additional administrative funds to deal with the increase in demand resulting from job and income losses.

SNAP is not only an effective mechanism for helping households with low incomes put food on the table; it also provides counter-cyclical help in recessions, which means that its positive impact extends beyond those directly receiving the benefits. Every dollar in new SNAP benefits increases gross domestic product by about $1.50 during a weak economy, according to a recent Department of Agriculture (USDA) study.[38]

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act and CARES Act provided Puerto Rico with a little over $295 million in additional nutrition assistance to supplement its NAP funding. The additional funding represents roughly a 15 percent increase over NAP’s annual funding from the federal government, and is less than what was provided in additional benefits for SNAP.[39] While this additional funding will partially offset the increased need for nutrition assistance from job and income losses from the economic slowdown, it is not sufficient to cover the Commonwealth’s increased need. (Unlike SNAP, which automatically expands to meet rising need, Puerto Rico receives nutrition assistance in the form of a block grant that does not increase with need.)

Before the crisis, benefits were already lower in Puerto Rico than they likely would have been under SNAP rules, and eligibility rules were constrained by available funding. As many as one-third of Puerto Rico adults were already struggling to afford adequate food before the pandemic, research indicates.[40] In addition to covering new households affected by the economic downturn, increased funding for NAP could help the Commonwealth increase benefit levels.

The CARES Act makes substantial, one-time economic impact payments available to most people with low incomes, but it left out many immigrants and their U.S. citizen family members. Specifically, households where the tax filer or the spouse do not have a Social Security number (but file a tax return using an Individual Tax Identification Number or ITIN) are entirely ineligible for stimulus payments, even if one spouse and children in the household are U.S. citizens. New coronavirus response legislation should make stimulus payments available to individuals who use an ITIN on their federal tax return.

Additionally, the next legislative package should ensure that immigrants and their families can access COVID-related health care as well as supports like Medicaid and SNAP that can ease hardship during the crisis, without the fear that doing so may jeopardize their ability to live together in the United States. The Trump Administration’s public charge rule and other policies have left many immigrants and their families afraid to access public benefits for which they are eligible. Because these policies are harsh, opaque, and confusing, many families that include immigrants have avoided benefits even when the public charge-related policy changes do not apply to them or are very unlikely to affect them.

The pressures on state and local finances from the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic fallout are mounting and becoming severe. The Families First and CARES acts have provided some emergency fiscal relief, but far too little to enable states and localities (including the territories and tribal governments) to respond to the immediate public health emergency, absorb increased program costs, and avoid sharp spending cuts that would deepen and prolong a recession while hurting individuals and families who rely on public services like education, health care, and transportation.

States and localities are important sources of funding for programs that help people with the greatest needs. They fund homeless shelters, child care for low-income children, employment and training programs to help people find work, services for people coming out of jails and prisons, behavioral health programs for people dealing with mental health or substance use issues, transportation systems that help people without cars get to work, and increasingly, construction of affordable housing. Without additional resources to address the significant budget shortfalls states are facing, many of these programs could be subject to significant cuts, potentially worsening the circumstances of families who struggle the most to pay their rent, put food on the table, afford health care, and meet other basic needs.

An important part of fiscal relief for states and territories is providing states with additional resources to expand and strengthen Medicaid coverage.[41] In the next economic response package, Congress should increase the federal share of state Medicaid expenditures, with the extent and duration of the increase tied to state-specific economic indicators.

The next relief package should also temporarily raise the federal government’s portion of Medicaid expansion costs to 100 percent, up from the current 90 percent. Several states are close to adopting or implementing expansion, which financial incentives could help finalize — opening up comprehensive coverage to hundreds of thousands of people who are already uninsured and many others who risk becoming uninsured in coming months. This is particularly important for low-income Black, Native American, and Hispanic people in states that have not expanded Medicaid; as stated above, early evidence shows they may be disproportionately impacted by COVID-19’s poor health outcomes and, if uninsured, need help paying their medical bills.