Policymakers are appropriately considering additional stimulus measures in the face of mounting job losses and other dire economic signs due to COVID-19. A top item on their list should be raising SNAP (food stamp) benefits as a way of mitigating hardship and injecting fast, high “bang-for-the-buck” stimulus into the economy.

SNAP has proven to be one of the most effective mechanisms available both to reach low-income households and to provide counter-cyclical help in recessions. That’s why we recommend that policymakers increase the SNAP maximum allotment by 15 percent until economic measures show that unemployment is no longer significantly elevated. That would amount to about $25 more per person per month, or just under $100 per month in food assistance for a family of four.

SNAP benefits are one of the fastest, most effective forms of economic stimulus because they quickly inject money into the economy — and a SNAP benefit increase can be implemented virtually immediately. Low-income individuals generally spend all of their income to meet daily needs such as shelter, food, and transportation; every SNAP dollar that a low-income family receives enables the family to spend an additional dollar on food or other items. Some 80 percent of SNAP benefits are redeemed within two weeks of receipt; 97 percent are spent within a month. That’s why the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Moody’s Analytics rate SNAP expenditures as one of the most effective and efficient supports for the economy during downturns, measured on a “bang-for-the-buck” basis. Every dollar in new SNAP benefits increases Gross Domestic Product by about $1.50 during a weak economy, according to a recent Department of Agriculture (USDA) study.[1]

Increasing SNAP benefits also helps families afford adequate food. Evidence from the Great Recession shows the effect that higher SNAP benefits can have on easing hardship; the 2009 Recovery Act’s benefit increase helped lessen food insecurity (the lack of consistent access to nutritious food because of limited resources) among SNAP households.

In addition to the benefit increase, we recommend that policymakers include several additional changes to SNAP and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in a future major economic stimulus package, including:

- Suspending the three-month time limit on SNAP benefit receipt that adults aged 18-50 who aren’t employed and aren’t raising minor children face, until the economy has recovered;

- Suspending implementation of several Administration regulations that would take away food assistance from 4 million low-income individuals;

- Ensuring that Puerto Rico has the funding and tools to provide food assistance during the crisis on a par with the states;

- Supplementing states’ funding for SNAP administration; and

- Adopting two changes to WIC that would extend the program’s reach to young children before they reach school age, as well as protect babies from losing WIC coverage during the downturn.

To be sure, the food assistance provisions of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act are providing some additional SNAP benefits to many households. But that expansion will only last during the public health emergency, and it leaves out nearly 40 percent of SNAP households, including those who have the lowest incomes and thus have the most difficulty affording adequate food. Some 5 million children are among those now left out.

Effective economic stimulus and recovery measures work by increasing the demand for goods and services when there is insufficient existing demand to keep businesses operating at capacity and to generate full employment. Measures that increase demand begin to put people back to work during times when business and consumer confidence is low and economic activity is declining. Such measures continue to do so in the early stages of a recovery from a recession.[2]

SNAP benefits are one of the fastest, most effective forms of economic stimulus because they get money into the local economy quickly for two reasons: first, states can issue additional SNAP benefits to SNAP households without delay, and second, recipients will spend virtually all of the additional resources rather than save them. States can increase SNAP benefits through the same channels as regular SNAP benefits, within days or weeks of enactment. And since SNAP recipients have low incomes, they generally need to spend their resources to meet their daily needs such as shelter, food, and transportation. Additional resources from SNAP also can free up other household income for other needed goods and services.

Some 80 percent of SNAP benefits are redeemed within two weeks of receipt; 97 percent are spent within a month.[3] CBO and Moody’s Analytics rate SNAP expenditures as one of the most effective ways to boost economic growth and job creation in a weak economy.[4]

Every dollar in new SNAP benefits spent when the economy is weak and unemployment elevated would increase the gross domestic product by $1.54, a recent USDA study estimated. Previous studies have estimated this effect to be as high as $1.80 for every new dollar in SNAP benefits during a recession.[5] Increases in SNAP benefits have the largest effects on spending for food and durable goods, and on income and jobs in industries such as manufacturing, trade, and transportation.[6] As the USDA study explains:

The impact of this increased spending by SNAP households “multiplies” throughout the economy as the businesses supplying the food and other goods — and their employees — have additional funds to make purchases of their own. This multiplier effect on the economy may extend well beyond the initial money provided to SNAP participants.

SNAP, by design, operates as an “automatic stabilizer” because its participation and spending can expand automatically when the economy experiences a downturn that raises unemployment and reduces household incomes. The program experienced large but temporary growth during and after the Great Recession; caseloads expanded significantly between 2007 and 2011 as the recession and sluggish economic recovery dramatically increased the number of low-income households that qualified and applied for help. Beyond the automatic stimulus from caseload growth, in the 2009 Recovery Act, policymakers raised the level of maximum SNAP benefits beginning in April 2009, in recognition of SNAP’s effectiveness at providing economic stimulus. During the period that this increase was in effect, through late 2013, these payments delivered $40 billion in economic stimulus (in addition to the increase in SNAP expenditures resulting from caseload growth).[7]

Increasing SNAP benefits also helps families afford adequate food. While SNAP is effective at reducing “food insecurity” (lack of consistent access to nutritious food because of limited resources), there is substantial evidence that the SNAP benefits levels fall short of what many participants need to obtain a healthy diet throughout the month, and that additional benefits would further reduce food insecurity.[8]

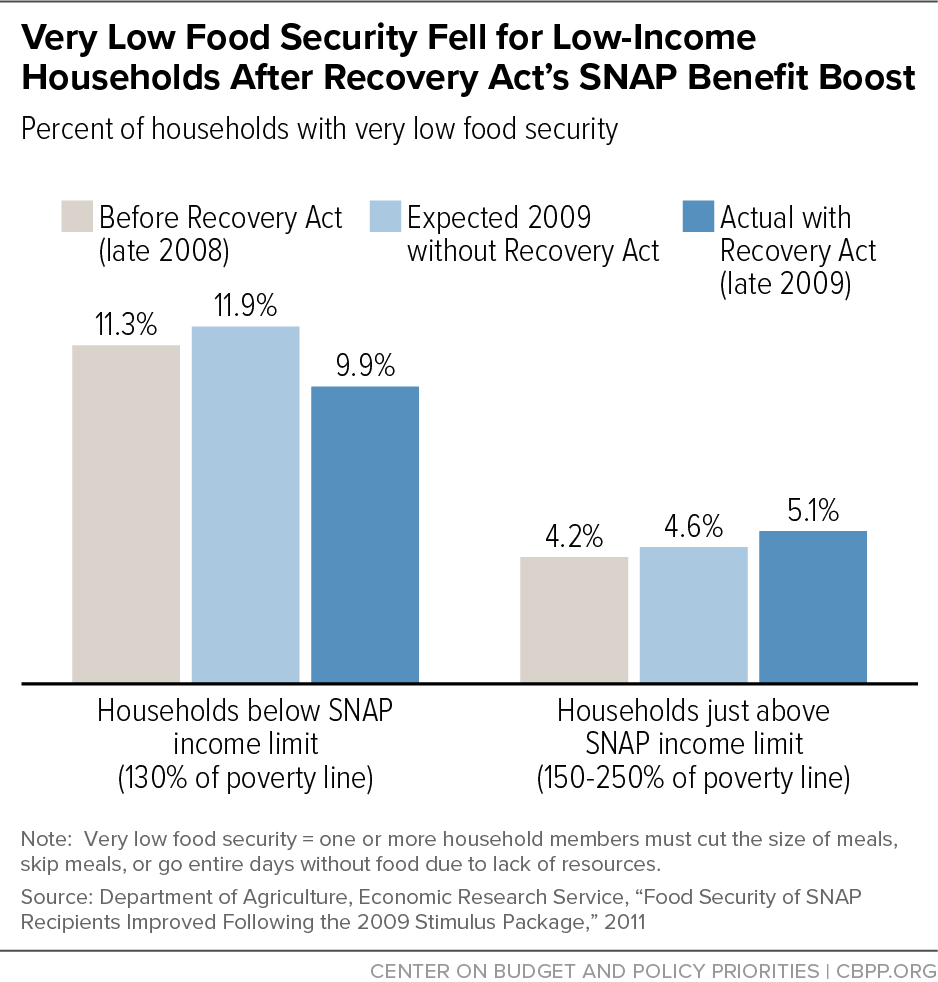

The SNAP benefit increase in the 2009 Recovery Act lessened food insecurity among SNAP recipients, according to USDA researchers. The researchers expected the share of households with “very low food security” — meaning that they had to take steps such as skipping meals because they couldn’t afford sufficient food — to rise in 2009 as a result of the recession’s harsh impact on incomes and employment. Yet very low food security actually fell that year — the year the SNAP benefit increase took effect — among households with incomes low enough to qualify for SNAP (below 130 percent of the poverty line).[9] Among households with somewhat higher incomes, in contrast, very low food security increased in 2009, as expected. (See Figure 1.)

This evidence suggests that the Recovery Act’s benefit increase helped cushion the blow of the recession by providing more income for families to purchase food. Another study found that, as inflation eroded the value of the Recovery Act benefit boost between 2009 and 2011, very low food security began to rise among low-income SNAP households, from 12.1 percent in 2009 to 13.8 percent in 2011 (at a time when low food security did not rise among low-income households not receiving SNAP). The study controlled for other factors that might have influenced household food security, such as income and employment.[10] The results of these studies indicate a strong relationship between SNAP benefit levels and recipients’ food insecurity.

Without the Recovery Act’s SNAP benefit boost, poverty would have risen more for SNAP recipients than it did. The SNAP increases in the Recovery Act alone kept close to 1 million people out of poverty in 2010, in addition to the 3 million that the existing SNAP benefits kept out of poverty, a 2011 CBPP analysis estimated.[11]

To provide economic stimulus and push back against the increased hardship the coronavirus is causing, we recommend a temporary 15 percent increase in the SNAP maximum allotment level (known as the Thrifty Food Plan, or TFP).[12] Such a measure, which would be similar to the SNAP benefit increase included in the 2009 Recovery Act, would increase SNAP benefits by about $25 per person per month, or, an average of about 20 percent.

If the increase took effect in June 2020, it would increase SNAP spending by about $4 to $6 billion over the remainder of fiscal year 2020 and $10 to $15 billion over fiscal year 2021.[13] The lower figures in these ranges assume pre-crisis assumptions about the number of participating SNAP households; the higher bounds, for illustrative purposes, assume that the share of the population that participates in SNAP in each state will rise within several months to the higher of: 1) the share of the state’s population that participated at the peak of SNAP participation following the last recession or 2) a 5 percentage-point increase in the share above the current level.[14] The impact would be larger still if more households apply for SNAP than during the last recession and its aftermath, which is possible given the early indications of the severity of the current downturn. (See Tables 1 and 2 at the end of this paper for state-by-state estimates of the average increases and total additional SNAP benefits.)

SNAP benefits are based on a household’s expected contribution toward buying food. Households with no disposable, or net, income (after deductions for certain key household expenses) receive the maximum SNAP allotment for their household size, while households with some net income receive a benefit equal to the difference between the maximum allotment for their household size and their expected contribution (30 percent of their net income).

A 15 percent increase in the maximum SNAP benefit would raise SNAP benefits for all participating households, and by the same amount for all households of the same size (with one exception, discussed below). In 2020, one-person households would receive an added $29 a month; households of two, three, and four persons would receive an added $54, $76, and $97 a month, respectively. Households receiving less than the maximum benefit would receive the same fixed dollar increase, so their average benefit increase would be somewhat larger in percentage terms than the increase to the maximum benefit. Across all SNAP households, average benefits would be about 20 percent higher in 2020 as a result of the 15 percent increase to the maximum benefit.

The one exception would be that households that receive SNAP’s minimum benefit, which is available to eligible one- and two-person households that otherwise qualify for little or no benefit, would receive an additional $2 a month — $18 instead of $16. Some 1.8 million households receive the minimum benefit; the majority are households with elderly members. If policymakers wanted to provide additional SNAP to these households they could raise the minimum benefit to something like $30 a month, which would add another $200 million a year in SNAP spending.

In addition to SNAP benefit levels, the TFP also is the basis for annual inflation adjustments for the capped block grant that provides nutrition assistance to households in Puerto Rico and American Samoa, as well as for much of the federal funding that goes to the emergency food network. Thus, a 15 percent increase in SNAP’s maximum allotments can be designed in such a way that the increase flows through to these other critical programs. This was the approach taken in the 2009 Recovery Act for the nutrition assistance block grant for Puerto Rico and American Samoa. The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) received additional funds from other appropriations in 2009.

Both the block grant and TEFAP received modest additional funding in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. But those bills were designed only to address short-term needs related to the pandemic. The severity and likely length of the economic downturn warrant a more significant increase to equip both programs to deal with the heightened need. At a minimum, they should receive roughly a similar percentage increase to that for SNAP. Puerto Rico may need still more funding to adequately provide food assistance, given its underlying economic problems — which the current crisis has compounded — as well as the insufficiency of its current nutrition block-grant funding.[15]

As we discuss below, we also recommend extending the Families First Pandemic-EBT provision to Puerto Rico, which operates the federal school meals program but was inadvertently left out of the provision.

We recommend setting SNAP benefits at a level 15 percent higher than the 2020 TFP until economic measures show that unemployment is no longer substantially elevated, or until the program’s regular annual inflation adjustments overtake it, whichever occurs first. The recession’s rapid onset and unusual genesis have created substantial uncertainty about how long economic stimulus measures will be needed. If, like after the Great Recession, it takes several years for the economic recovery to reach lower-wage workers, it would make sense to leave the SNAP increase in place for such a period. Based on the surge in unemployment insurance claims starting in March, various forecasters, including Goldman Sachs and CBO, project a sharp near-term spike in the unemployment rate to Great Recession or higher levels, with unemployment then remaining elevated for an uncertain duration but at least through much or all of 2021. And if the economy recovers more quickly, it then will be appropriate to end the temporary SNAP increase earlier, as stimulus measures will no longer be necessary.

To account for the uncertain trajectory of the recession, we recommend that policymakers design a “trigger” so the SNAP benefit increase ends automatically based on when certain economic indicators are met. Such an approach is preferable to ending the stimulus measure too soon and expecting Congress to revisit the issue in a timely manner, or leaving the increase in effect beyond when it is needed to help respond to the economic downturn.[16]

An approach could be used here similar to the approach we recommend for the unemployment insurance (UI) measures included in the CARES Act. Those UI expansions are now slated to expire this year, some over the summer and others at the end of the year; but the economic slump will likely last well past then. We suggest that the UI eligibility and benefit improvements be turned off when there are solid indications that the economy is recovering significantly — for example, that the three-month unemployment rate has fallen for two straight months and is within 1.5 percentage points of its level before the crisis. (Since the unemployment rate prior to the recession was 3.5 percent, that level would be 5 percent.)[17]

Another option would be to scale back the 15 percent bump in 5 percentage-point increments annually once the labor market has recovered, as measured by the unemployment rate returning to a level close to pre-recession levels. Alternatively, policymakers could end the entire benefit increase when such a trigger based on labor-market indicators is pulled.

Include Other SNAP and WIC Changes in Next Major Stimulus Package

In addition to the 15 percent increase to SNAP maximum benefits, we recommend that policymakers include several additional changes to SNAP and WIC in the next economic stimulus package.[18]

Preserving and Extending Eligibility for SNAP

For SNAP, we recommend:

-

Suspending the three-month limit on SNAP benefit receipt until the economy has recovered. The three-month limit for adults aged 18-50 who aren’t employed or in training 20 hours per week and aren’t raising children at home should be suspended in all states in recognition of the severe effect the crisis is having on job opportunities. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act suspends the time limit until the end of the month after the public health emergency declaration is lifted. The adverse effects of the economic slowdown on labor market opportunities for workers in low-wage occupations, however, will extend beyond the end of the public health emergency, so the suspension should remain in effect until the economy improves.

In mid-March, a federal district court issued a nationwide injunction temporarily halting a Trump Administration final rule that would sharply constrain states’ ability to obtain waivers of the three-month time limit in areas without sufficient jobs. Like the provision of the Families First Act, this decision is temporary. A longer-term solution is needed given the economic downturn’s impact on the job market.[19]

- Suspending implementation of two other pending regulations. The Administration currently is seeking large cuts in SNAP through both the final regulation mentioned above and two other regulations that the Administration has proposed but hasn’t yet promulgated as final rules. If all three regulatory changes go into effect, they will take away SNAP assistance from 4 million low-income individuals and cut SNAP spending by nearly $50 billion over ten years, according to the Administration’s own estimates.[20] Cutting back SNAP eligibility during an economic downturn runs counter to the goal of boosting aggregate demand to temper the downturn’s severity. We recommend that the next stimulus package include a provision, to stay in effect as long as the economy remains weak, barring the Administration from implementing these rules.

-

Providing supplemental funding for states’ SNAP administrative costs. Many states have been inundated by SNAP applications, and the demand is likely to continue to grow as the unemployment rate rises further.[21] This is happening at a time when states’ workforces are stretched due to offices that are closed to walk-in traffic (and have been reduced in many areas because of illness and school closures). Despite recent advances in online services for participants, before the public health emergency the SNAP application process in most states entailed substantial in-person interaction between clients and state eligibility workers, and many states had not developed telework capacity.

Once the public health emergency lifts, we expect states to be far behind in processing SNAP applications, even as more applications continue to be submitted as a result of the economic downturn. To help states with the costs of rising demand for services, implementing temporary programmatic changes, and preparing for the possibility of more remote work, we recommend that the next stimulus package make available to states an amount equal to 10 percent of the federal payments provided for states’ SNAP administrative costs in the most recent fiscal year. This provision should be in effect during the period that the SNAP benefit increase is in effect. This measure, as well, was included in the 2009 Recovery Act.

- Improving the Families First Pandemic-EBT provision. The Families First P-EBT provision gives states the option to provide school-aged children who are missing out on free and reduced-price meals due to school closures with benefits that are provided via a SNAP or SNAP-like electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card and are equal to the federal reimbursement rate for free school breakfasts and lunches.[22] Only a handful of states have implemented this option to date; some states have suggested the option could be streamlined and reworked to offer states more flexibility on how to use it, as well as extending the option so that it can cover the period when, in normal times, low-income children would be receiving meals through summer programs or summer meal sites. Many of those sites and programs could be closed this summer throughout much of the country. In addition, as noted above, the Pandemic-EBT option should be extended to Puerto Rico, which operates the federal school meals programs on the same basis as the states but was left out of the P-EBT option in the Families First Act.

WIC is a national public health and nutrition program that each month serves more than 6 million low-income women, infants, and young children at nutritional risk across the United States. Policymakers should ensure that this important nutrition program is available and accessible.

The Families First Act included several useful provisions that allow states to seek waivers to enroll, recertify, and issue WIC benefits to low-income families without requiring the usual in-person appointments, as well as to ease other requirements to ensure ongoing service to eligible households.[23] We recommend two additional changes to WIC to extend the program’s reach to more young low-income children before they reach school age and to protect low-income infants from losing WIC coverage during the downturn. While these changes would be sensible permanent improvements to the programs, for the purposes of a stimulus package they would likely need to be temporary.

- Temporarily extend WIC eligibility to age six. Temporarily extending WIC eligibility for children by one year — until their sixth birthday — would ensure that children receive WIC benefits until they become eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. National Center for Education Statistics data indicate that roughly half of children start kindergarten after the age of 5½, which means these children could face six months or more without access to either WIC or school meals.[24] Extending WIC eligibility to age 6 could protect more children from food insecurity during the health and economic crisis and improve their diet, health, and development.

- Temporarily extend WIC certification periods for infants to two years. Giving states the option to certify infants participating in WIC for two years rather than one would facilitate infants staying on WIC longer, which is associated with better diets.[25] Many families drop out of the program when an infant turns one, in part because of the burdensome recertification appointment, a problem that the current crisis is exacerbating. Providing states with the flexibility to extending the certification period would also help streamline WIC administration at a time when there will be increased demand for the program that stretches administrative capacity.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act provided several temporary, but important nutrition program flexibilities and benefit changes to supplement existing programs in addressing the short-term public health emergency.[26] These provisions are providing important help to families and states, but they expire at the end of the public health emergency as declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Yet an elevated need for food assistance and economic stimulus almost certainly will last beyond the point when the health emergency is declared over, because unemployment is expected to remain high for quite some time after that. In addition, SNAP provisions of the Families First Act, while quite helpful, leave out millions of very poor families.

The Families First Act provides authority for USDA to approve state waiver requests to temporarily raise SNAP allotments to address increased food needs. USDA has interpreted the new authority as allowing states to increase household benefits to the level of the SNAP maximum allotment for those households that don’t otherwise receive the maximum allotment; all states are using this authority. However, the additional allotments are available only while federal and state emergency or disaster declarations are in effect. The timing of when those emergency designations will end is uncertain, but we expect the 15 percent increase in the maximum benefit would carry through during the duration of the economic downturn as a way of addressing both food insecurity and the need for longer-term economic stimulus.

While these SNAP emergency allotments are providing a measure of economic stimulus and alleviating hardship for the households receiving them, some 40 percent of SNAP households already receive the SNAP maximum benefit and thus cannot receive any additional resources for food under this provision. These SNAP households are, by definition, the SNAP households with the lowest incomes; they receive the maximum benefit because they have no disposable income available to purchase food under the SNAP benefit calculation rules.[27]

In total, 12 million of the poorest individuals participating in SNAP are not being helped by the current SNAP emergency allotments. Those not helped include 5 million children, many of whom are less than 5 years old, about 1 million households with elderly members and 600,000 households with people who have disabilities. These numbers will only grow as the incomes of more households decline and more households apply for SNAP benefits.

The 15 percent increase in the SNAP maximum benefit that we recommend as economic stimulus doesn’t change who is eligible for SNAP or the conditions under which they apply. Rather, it adds — on a temporary basis — a modest $25 a month per person to the SNAP benefit for those who are eligible under the program’s existing terms and conditions as set by Congress. The measure would both benefit millions of impoverished families and help in bolstering the weakened U.S. economy.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

|

|

|

Remainder of Fiscal Year 2020 (June-Sept. 2020) a |

Fiscal year 2021c |

|---|

| State |

Number of SNAP Households Prior to Pandemic b (thousands) |

Share of State Population Participating in SNAP Prior to Pandemic b |

Share of State Population That Participated in SNAP When Caseloads Were at the Peak Following Last Recession |

Estimated Total Benefit Increase Based on Pre-pandemic Caseloads (millions) |

Estimated Total Benefit Increase With Illustrative Assumptions About Caseload Increasesd (millions) |

Estimated Total Benefit Increase Based on Pre-pandemic Caseloads (millions) |

Estimated Total Benefit Increase With Illustrative Assumptions About Caseload Increasesd (millions) |

|---|

| Alabama |

338 |

14.5% |

19.1% |

$71 |

$96 |

$197 |

$265 |

| Alaska |

36 |

10.8% |

13.1% |

$11 |

$16 |

$30 |

$44 |

| Arizona |

371 |

10.8% |

17.5% |

$75 |

$123 |

$207 |

$337 |

| Arkansas |

157 |

11.5% |

17.2% |

$33 |

$50 |

$92 |

$138 |

| California |

2,155 |

10.2% |

11.5% |

$405 |

$603 |

$1,117 |

$1,663 |

| Colorado |

222 |

7.6% |

9.8% |

$44 |

$73 |

$121 |

$200 |

| Connecticut |

213 |

10.1% |

12.4% |

$36 |

$54 |

$100 |

$149 |

| Delaware |

59 |

12.3% |

16.9% |

$11 |

$16 |

$32 |

$44 |

| District of Columbia |

66 |

15.5% |

22.7% |

$11 |

$16 |

$30 |

$44 |

| Florida |

1,496 |

12.7% |

18.5% |

$274 |

$399 |

$756 |

$1,101 |

| Georgia |

633 |

12.8% |

21.2% |

$136 |

$226 |

$375 |

$623 |

| Hawaii |

80 |

10.9% |

13.9% |

$29 |

$42 |

$83 |

$122 |

| Idaho |

66 |

8.0% |

15.0% |

$14 |

$26 |

$38 |

$71 |

| Illinois |

897 |

14.0% |

16.1% |

$178 |

$241 |

$491 |

$666 |

| Indiana |

258 |

8.5% |

14.2% |

$57 |

$96 |

$157 |

$264 |

| Iowa |

147 |

9.6% |

13.7% |

$29 |

$44 |

$80 |

$122 |

| Kansas |

93 |

6.7% |

11.1% |

$20 |

$34 |

$54 |

$94 |

| Kentucky |

222 |

11.0% |

20.0% |

$47 |

$86 |

$131 |

$236 |

| Louisiana |

370 |

17.0% |

21.4% |

$79 |

$103 |

$219 |

$283 |

| Maine |

86 |

11.5% |

19.2% |

$15 |

$25 |

$41 |

$68 |

| Maryland |

329 |

10.0% |

13.5% |

$58 |

$87 |

$160 |

$240 |

| Massachusetts |

456 |

11.0% |

13.3% |

$76 |

$111 |

$210 |

$305 |

| Michigan |

612 |

11.5% |

19.7% |

$115 |

$197 |

$318 |

$544 |

| Minnesota |

202 |

7.0% |

10.3% |

$39 |

$68 |

$109 |

$187 |

| Mississippi |

204 |

14.6% |

22.5% |

$40 |

$62 |

$109 |

$169 |

| Missouri |

314 |

10.9% |

16.0% |

$67 |

$98 |

$184 |

$271 |

| Montana |

52 |

9.9% |

13.1% |

$10 |

$15 |

$28 |

$42 |

| Nebraska |

71 |

8.0% |

9.8% |

$15 |

$24 |

$41 |

$67 |

| Nevada |

221 |

13.5% |

15.2% |

$40 |

$55 |

$110 |

$151 |

| New Hampshire |

39 |

5.3% |

9.1% |

$7 |

$14 |

$20 |

$39 |

| New Jersey |

342 |

7.6% |

10.4% |

$65 |

$108 |

$179 |

$296 |

| New Mexico |

223 |

21.3% |

22.1% |

$45 |

$55 |

$123 |

$152 |

| New York |

1,478 |

13.2% |

16.5% |

$278 |

$383 |

$772 |

$1,064 |

| North Carolina |

597 |

11.7% |

18.0% |

$123 |

$189 |

$340 |

$521 |

| North Dakota |

23 |

6.3% |

9.2% |

$5 |

$9 |

$13 |

$24 |

| Ohio |

684 |

11.8% |

16.0% |

$132 |

$188 |

$363 |

$518 |

| Oklahoma |

272 |

14.5% |

16.6% |

$58 |

$77 |

$159 |

$214 |

| Oregon |

345 |

13.8% |

21.2% |

$58 |

$90 |

$161 |

$247 |

| Pennsylvania |

941 |

13.5% |

14.6% |

$167 |

$228 |

$458 |

$627 |

| Puerto Rico and American Samoae |

712 |

40.7% |

Not Applicable |

$292 |

$292 |

$267 |

$267 |

| Rhode Island |

89 |

13.9% |

17.2% |

$15 |

$20 |

$41 |

$55 |

| South Carolina |

269 |

11.2% |

18.6% |

$56 |

$92 |

$153 |

$253 |

| South Dakota |

37 |

8.8% |

12.6% |

$8 |

$12 |

$22 |

$34 |

| Tennessee |

417 |

12.7% |

20.9% |

$87 |

$143 |

$241 |

$394 |

| Texas |

1,414 |

11.3% |

16.2% |

$315 |

$454 |

$865 |

$1,249 |

| Utah |

71 |

5.1% |

10.8% |

$16 |

$35 |

$45 |

$95 |

| Vermont |

39 |

10.8% |

16.3% |

$7 |

$10 |

$19 |

$28 |

| Virginia |

338 |

8.1% |

11.5% |

$69 |

$112 |

$191 |

$309 |

| Washington |

471 |

10.5% |

16.2% |

$80 |

$124 |

$220 |

$341 |

| West Virginia |

162 |

17.0% |

20.3% |

$29 |

$38 |

$81 |

$104 |

| Wisconsin |

310 |

10.3% |

15.0% |

$55 |

$82 |

$152 |

$225 |

| Wyoming |

12 |

4.4% |

6.7% |

$3 |

$5 |

$7 |

$15 |

| Guam |

15 |

25.2% |

29.7% |

$6 |

$7 |

$17 |

$21 |

| Virgin Islands |

10 |

20.0% |

26.4% |

$3 |

$4 |

$8 |

$10 |

| United States |

19,022 |

11.4% |

15.2% |

$4,029 |

$5,674 |

$10,580 |

$15,122 |

| TABLE 2 |

|---|

| |

Average Monthly Benefit Increase from a 15% Increase in SNAP Maximum Benefits |

|

|---|

| State |

Average Monthly Benefits per Household, October 2019 to January 2020 |

Per Household |

Per Person |

Approximate Average Monthly Benefits Per Household, Including Increase |

|---|

| Alabama |

$251 |

$52 |

$25 |

$303 |

| Alaska |

$379 |

$77 |

$34 |

$456 |

| Arizona |

$257 |

$53 |

$24 |

$310 |

| Arkansas |

$242 |

$55 |

$24 |

$297 |

| California |

$231 |

$50 |

$25 |

$281 |

| Colorado |

$238 |

$50 |

$25 |

$288 |

| Connecticut |

$227 |

$43 |

$25 |

$270 |

| Delaware |

$236 |

$48 |

$24 |

$284 |

| District of Columbia |

$217 |

$40 |

$25 |

$257 |

| Florida |

$219 |

$46 |

$25 |

$265 |

| Georgia |

$266 |

$53 |

$25 |

$319 |

| Hawaii |

$459 |

$91 |

$47 |

$550 |

| Idaho |

$237 |

$54 |

$24 |

$291 |

| Illinois |

$246 |

$49 |

$25 |

$295 |

| Indiana |

$261 |

$55 |

$25 |

$316 |

| Iowa |

$234 |

$49 |

$24 |

$283 |

| Kansas |

$233 |

$53 |

$25 |

$286 |

| Kentucky |

$256 |

$52 |

$24 |

$308 |

| Louisiana |

$270 |

$54 |

$25 |

$324 |

| Maine |

$201 |

$45 |

$24 |

$246 |

| Maryland |

$211 |

$45 |

$24 |

$256 |

| Massachusetts |

$209 |

$43 |

$25 |

$252 |

| Michigan |

$222 |

$46 |

$25 |

$268 |

| Minnesota |

$203 |

$48 |

$25 |

$251 |

| Mississippi |

$240 |

$51 |

$23 |

$291 |

| Missouri |

$262 |

$53 |

$25 |

$315 |

| Montana |

$231 |

$50 |

$24 |

$281 |

| Nebraska |

$248 |

$55 |

$24 |

$303 |

| Nevada |

$216 |

$45 |

$24 |

$261 |

| New Hampshire |

$190 |

$48 |

$25 |

$238 |

| New Jersey |

$229 |

$49 |

$24 |

$278 |

| New Mexico |

$238 |

$51 |

$25 |

$289 |

| New York |

$240 |

$48 |

$27 |

$288 |

| North Carolina |

$237 |

$44 |

$25 |

$281 |

| North Dakota |

$241 |

$52 |

$25 |

$293 |

| Ohio |

$245 |

$49 |

$24 |

$294 |

| Oklahoma |

$252 |

$54 |

$25 |

$306 |

| Oregon |

$206 |

$42 |

$25 |

$248 |

| Pennsylvania |

$218 |

$46 |

$24 |

$264 |

| Rhode Island |

$221 |

$41 |

$25 |

$262 |

| South Carolina |

$256 |

$51 |

$24 |

$307 |

| South Dakota |

$267 |

$55 |

$25 |

$322 |

| Tennessee |

$255 |

$51 |

$25 |

$306 |

| Texas |

$271 |

$56 |

$24 |

$327 |

| Utah |

$266 |

$60 |

$25 |

$326 |

| Vermont |

$210 |

$44 |

$25 |

$254 |

| Virginia |

$241 |

$51 |

$25 |

$292 |

| Washington |

$207 |

$43 |

$25 |

$250 |

| West Virginia |

$205 |

$47 |

$24 |

$252 |

| Wisconsin |

$205 |

$45 |

$23 |

$250 |

| Wyoming |

$250 |

$56 |

$25 |

$306 |

| Guam |

$536 |

$105 |

$36 |

$641 |

| Virgin Islands |

$343 |

$64 |

$32 |

$407 |

| United States |

$238 |

$49 |

$25 |

$287 |