The economy was in the longest expansion on record before the COVID-19 pandemic, but a sharp decline in economic activity is now inevitable, with unemployment insurance claims skyrocketing and many forecasters saying that the economy has already entered a recession. The last recession — the Great Recession — was a stark reminder of the need to lessen the human hardship and economic dislocation associated with a recession. It left key lessons for policymakers, who should now use a wide array of available policy tools to keep this and future downturns as short and shallow as possible.

Economists’ thinking about anti-recessionary policies has evolved in the last decade, informed in part by the limits of conventional monetary policy that fighting the Great Recession revealed. This experience generated renewed attention among policy economists to the importance of fiscal stimulus (temporary increases in government spending and reductions in government revenues) in supporting overall spending and employment when the economy weakens and preventing serious and long-lasting damage when recessions do occur.

In March, lawmakers enacted three increasingly sizeable pieces of legislation to address the harm that the pandemic and efforts to contain it are causing.[1] One of the most important lessons from the Great Recession is that they should be prepared to do more. While the Great Recession measures were substantial and prevented an even more severe recession, they ended prematurely and were insufficient to promote a robust recovery. The protracted period of high unemployment and underemployment after the economy stopped contracting and began to grow again in June 2009 continued to generate human hardship and hurt long-term growth. Because lawmakers did not include provisions in the recently enacted coronavirus legislation to “trigger” additional stimulus automatically, based on further deterioration in economic conditions, they must be prepared to enact additional measures as conditions require and to ensure they remain in place until the recovery is clearly underway.

The following account describes the importance of keeping recessions as short and shallow as possible and how both the economy and economists’ views have changed since the Great Recession. It then provides a set of principles and policies for fiscal stimulus informed by lessons learned in the Great Recession and its aftermath. (This analysis provides background and general policy principles; CBPP has also released a number of analyses directly addressing the needs of families hit hard by COVID-19 and the resulting economic fallout.[2])

In brief:

- Recessions have profound human and economic costs. Prolonged unemployment harms not only workers’ job prospects and lifetime earnings but also the health and well-being of them and their families. Workers without a college degree and workers of color are the most vulnerable to these adverse effects. Moreover, long unemployment spells and diminished demand for goods and services in a recession erode job skills among unemployed workers and reduce business investment, which can depress the economy’s productive capacity long past the end of the recession.

- Interest rates are considerably lower now than they were in the two decades leading up to the Great Recession. The Federal Reserve has already exhausted the room it had for its standard approach of cutting short-term interest rates to offset an economic downturn and stimulate a recovery in response to COVID-19. The Fed is proceeding with unconventional measures to support economic activity similar to those used in the Great Recession and its aftermath, as well as significant emergency measures to stabilize financial markets in the pandemic. Yet, fiscal measures are still required.

- Fiscal policy has a greater role to play in fighting recessions and stimulating recoveries than academic economists’ policy advice reflected prior to the Great Recession, especially in light of the limits to conventional monetary policy. Strengthening the fiscal policy response to a weakening economy requires more robust “automatic stabilizers” — the features of tax laws and spending programs like unemployment insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program) that automatically reduce income losses and support consumer spending in a downturn — together with a willingness of policymakers to enact additional temporary discretionary measures when the automatic stabilizers alone are insufficient, as is the case now with the pandemic.

- Fiscal stimulus is most effective if: 1) it is implemented as early as possible in a recession; 2) it is directed to individuals and entities who will spend any additional resources they receive quickly; 3) it errs on the side of being larger than ultimately necessary rather than smaller; and 4) its size and duration respond to changing circumstances.

- Concerns that the United States does not have the “fiscal space” — due to high levels of deficits and debt — to enact robust fiscal stimulus to minimize the human and economic costs of a recession are misguided. The United States has a long-term fiscal challenge, not an immediate debt crisis. Deficit and debt concerns should go on the back burner in a recession.

- The following are among the most important policies that meet the criteria for effective fiscal stimulus:

- Providing additional weeks of unemployment insurance and raising the weekly benefit level;

- Raising the maximum SNAP benefit level and ensuring that unemployed adults have access to food assistance;

- Providing state fiscal relief by reducing the percentage of Medicaid spending for which states are responsible (by increasing the federal matching rate) and giving states, tribes, and localities temporary block grants or other flexible funding to maintain needed services such as education;

- Providing cash assistance to people facing economic insecurity through monthly or one-time cash payments that can help address both emergencies and ongoing basic needs, as well as through expansions of refundable tax credits;

- Implementing a subsidized jobs program for low-income workers, although the special circumstances of COVID-19 require waiting until after the health crisis diminishes and such programs can be undertaken safely; and

- Increasing housing assistance to prevent a sharp rise in evictions and homelessness.

- A recession stemming from COVID-19 also requires additional measures to deal with unique circumstances, but for many of the measures above, policymakers should design them not only to provide robust immediate stimulus but also to permanently strengthen their function as automatic stabilizers that trigger on early in future recessions, provide stimulus appropriate to the magnitude of the downturn, and do not trigger off prematurely. Such trigger mechanisms can ensure that needed stimulus measures are timely and that they neither end prematurely nor remain in effect too long.

- As noted above, if a recession turns out to be deeper or last longer than initially anticipated, policymakers should be prepared to increase the size and/or duration of their fiscal policy response, including, if needed, following up with additional discretionary stimulus.

Keeping Recessions as Short and Shallow as Possible: Why It Matters

Pursuing and maintaining high employment and avoiding deep or long-lasting recessions are critical for most Americans’ well-being, but they are especially important for people who face greater hurdles finding good jobs and steady employment even in relatively good labor markets. Victims of recessions experience serious and lasting harm, as the International Monetary Fund found in its 2010 assessment of the human and social costs of recessions:

The human and social costs of unemployment are more far-reaching than the immediate temporary loss of income. They include loss of human capital, loss of lifetime earnings, worker discouragement, adverse health outcomes, and loss of social cohesion. Moreover, parents’ unemployment can affect the health and education outcomes of their children. The costs can be particularly high for certain groups, such as youth and the long-term unemployed.a

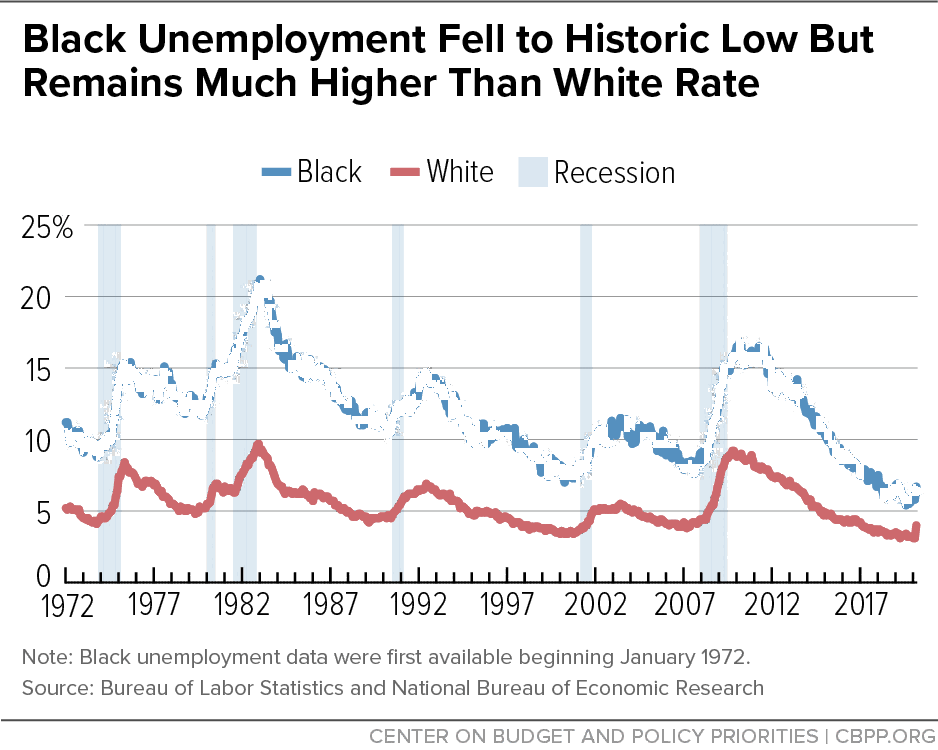

In the United States, racial disparities are particularly glaring. Black or African American and Hispanic/Latino unemployment rates fell to historically low levels in the 2009-2020 expansion, but they remained considerably higher than the white unemployment rate. Historically, black unemployment in the best of times has been little better than white unemployment in the worst of times (see chart).

Sustaining a high-employment economy is a necessary condition for making progress to close that gap, and that requires robust automatic stabilizers and effective discretionary fiscal stimulus to keep recessions as short and shallow as possible.

Recessions, of course, have immediate economic costs from unrecoverable output and income losses. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that in the half century before the Great Recession, net output and employment losses in recessions that outweighed increases in output above potential during booms caused actual gross domestic product to fall short of the output the economy was capable of producing by an average of about half a percentage point a year.b

Moreover, protracted unemployment spells can erode workers’ job skills or lead them to leave the labor force. And lower demand for their products can discourage businesses from investing in maintaining or expanding their capital stock of machines, factories, offices, and stores or from making other productivity improvements. The net result is slower growth in the economy’s long-run capacity to supply goods and services and slower income growth.c

a Mai Dao and Prakash Loungani, “The Human Cost of Recessions: Assessing It, Reducing It,” International Monetary Fund, November 11, 2010, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/IMF-Staff-Position-Notes/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Human-Cost-of-Recessions-Assessing-It-Reducing-It-24221.

b Congressional Budget Office, “Why CBO Projects That Actual Output Will Be Below Potential Output on Average,” February 2015, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/49890-gdp-projections.pdf.

c Laurence Ball, “The Great Recession’s long-term damage,” Vox, July 1, 2014, https://voxeu.org/article/great-recession-s-long-term-damage.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy Before the Great Recession

Before the Great Recession, the prevailing view among academic economists was that monetary policy should bear the primary responsibility for stabilizing economic activity, inflation, and employment. Fiscal policy’s role was largely confined to the automatic stabilizers built into existing tax laws and spending programs, such as progressive tax rates, unemployment insurance (UI), and SNAP.

That view reflected experience during the two-decade-long period prior to the Great Recession in which business-cycle fluctuations were significantly less volatile than in the previous four decades of the post-World War II era due to what economists perceived to be better monetary policy.[3] It also reflected a skepticism about policymakers’ ability to implement discretionary fiscal stimulus measures in a timely manner, even among economists who believed prompt enactment of well-designed measures could be effective in fighting recessions. (See box, “The Great Moderation,” for more about this period.)

Consistent with that view, when signs began to emerge in late 2007 that the expansion following the 2001 recession was threatened by weakness in the housing market and brewing turmoil in financial markets stemming from problems in the subprime mortgage market, economists generally emphasized that monetary policy should be the first line of defense. They argued that the Fed, which had gradually raised its short-term interest rate target from 1 percent in mid-2004 to 5.25 percent in June 2006, had ample room to cut interest rates to provide stimulus.

Economists who did not reject out of hand that fiscal policy could be helpful argued that any discretionary stimulus measures should be timely (i.e., stimulate new spending early in the recession), targeted (i.e., go to individuals and entities that would quickly spend any new resources they received), and temporary (i.e., expire when stimulus was no longer needed, so as not to add unnecessarily to budget deficits and debt without providing effective stimulus — or possibly even lead to overheating if they provide stimulus for too long).

The two decades preceding the Great Recession didn’t prepare policymakers for the challenges they would face in 2008-09. To the contrary, this period, known as the Great Moderation, was one in which inflation was relatively tame, recessions were relatively mild, and the then record-length 1990s expansion produced strong growth and very low unemployment. That experience stood in marked contrast to the preceding period from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, which included the stagflation of the early-to-mid 1970s — when inflation and unemployment coexisted and growth slowed — and the double-digit inflation of the late 1970s followed by the double-digit unemployment of the 1981-82 recession.

The 1990-1991 and 2001 recessions were both relatively short and mild (although the expansions coming out of each began sluggishly and unemployment continued to rise, peaking 15 and 19 months after the formal end of the recessions, respectively). The Fed had begun to cut its target interest rate prior to both of these recessions (the first steps toward interest-rate cuts totaling 5.8 and 4.5 percentage points, respectively) and did not begin to raise interest rates again until after unemployment began to fall. In both recessions, policymakers enacted additional weeks of emergency unemployment insurance (UI) payments for workers who exhausted their 26 weeks of regular UI benefits after the formal end of the recession but before unemployment peaked.

The 2001 recession ended what was then the longest economic expansion on record. As that expansion showed signs of faltering early that year, President Bush re-branded his campaign proposal for large permanent tax cuts as stimulus, but the only deliberate stimulus measure was a one-time (modest and non-refundable) tax rebate.

With unemployment still rising in early 2003, President Bush signed a second large tax cut that accelerated but did not expand some previously enacted tax cuts, expanded the child credit and included an advance payment mechanism for 2003, and increased certain business tax cuts. The 2003 package also included $20 billion in state fiscal relief

For the most part, however, the two Bush tax cuts provided limited stimulus while primarily benefiting high-income households and significantly increasing current and projected future budget deficits by lowering the path of future revenues substantially.

These positions were echoed in early 2008 by then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, who testified that the Fed had responded proactively by cutting its short-term interest rate target by a full percentage point to 4.25 percent between September and December 2007. Bernanke said that further cuts could be appropriate, and he agreed that well-designed fiscal measures could be helpful but poorly designed measures would be counterproductive.[4] Economists Jason Furman and Douglas Elmendorf similarly endorsed the priority of monetary policy and cautioned about the dangers of fiscal measures that were poorly timed, badly targeted, or permanently increased the deficit. They observed, however, that “if a sharp economic downturn appears imminent, and well-designed tax or spending changes could be implemented quickly, such fiscal stimulus could boost economic activity more quickly than monetary stimulus.”[5] A CBPP analysis added the recommendation that, to avoid the costs of not being ready if the economy did fall into a recession, policymakers should immediately assemble a stimulus package but wait for it to be triggered on by a specific indicator of further deterioration in economic conditions.[6]

Federal policymakers took reasonably timely steps early that year in response to evidence of a rising risk of recession.[7] In February 2008, President Bush and the Democratic Congress enacted a $152 billion package of individual income tax rebates, incentives to stimulate business investment, and steps to address the subprime mortgage crisis. In a series of steps from January to May, the Fed cut its interest rate target to 2 percent and adopted measures to contain the turmoil in financial markets. In July, with unemployment about a percentage point higher than a year earlier, the President and Congress enacted additional weeks of UI benefits.

In the second half of 2008, however, a meltdown in financial markets turned what might have been only a mild downturn into the Great Recession.

Unsustainable increases in bond and housing prices and excessive borrowing to purchase risky assets led to the financial market meltdown in the summer and fall of 2008, which in turn further weakened economic activity. As former Fed chair Janet Yellen, then President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, explained in early 2009:

Once this massive credit crunch hit, it didn’t take long before we were in a recession. The recession, in turn, deepened the credit crunch as demand and employment fell, and credit losses of financial institutions surged. . . . Consumers [pulled] back on purchases, especially on durable goods, to build their savings. Businesses [canceled] planned investments and [laid] off workers to preserve cash. And, financial institutions [shrank] assets to bolster capital and improve their chances of weathering the current storm.[8]

The first step of re-establishing financial market stability fell largely to the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which acted to restore liquidity that had evaporated in the crisis due to falling asset prices and the failure or near-failure of major financial institutions. Most notably, Congress eventually agreed to the controversial Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which established a $700 billion fund to give banks the capital they needed to continue to make loans.

To address the faltering economy, the Federal Reserve cut its target interest rate essentially to zero between October and December 2008, when it adopted a target range of 0 to 0.25 percent, which it maintained for the next five years. With no room for further conventional monetary stimulus via cuts in short-term interest rates, the Fed turned to unconventional measures, notably what would eventually be three rounds of large-scale purchases of longer-term assets — a policy known as quantitative easing — to try to lower longer-term interest rates and continue to provide needed stimulus.

On the fiscal policy front, President Obama and Congress enacted the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in February 2009. ARRA’s roughly $830 billion of tax cuts and spending measures were at the time by far the largest package of “Keynesian stimulus” in the post-World War II era. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), in its 2015 assessment of the impact of ARRA on employment and output, grouped the various provisions into the following four broad categories:[9]

- Providing funds to states and localities — for example, by raising the federal government’s share of Medicaid costs, providing funding for education costs, and increasing financial support for some transportation projects;

- Supporting people in need — such as by extending and expanding unemployment benefits and increasing benefits under SNAP;

- Purchasing goods and services — for instance, by funding construction and other investment activities that could take several years to complete; and

- Providing temporary tax relief for individuals and businesses — ranging from expansions of the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits and a new Making Work Pay tax credit to creating enhanced deductions for depreciation of business equipment and raising exemption amounts for the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

Economists Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi describe policymakers’ response to these developments as a major reason why the Great Recession did not become the United States’ “Great Depression 2.0,” and why the United States fared much better than many other countries in the global economic and financial crisis:

The policy responses to the financial crisis and the Great Recession were massive and multifaceted. . . . Not only did they include the aggressive use of standard monetary and fiscal policy tools, but new tools were invented and implemented on the fly in late 2008 and early 2009. Some aspects of the response worked splendidly, while others fell far short of hopes, and many were controversial — both in real time and even in retrospect. In total, however, we firmly believe that the policies must be judged a success. [10]

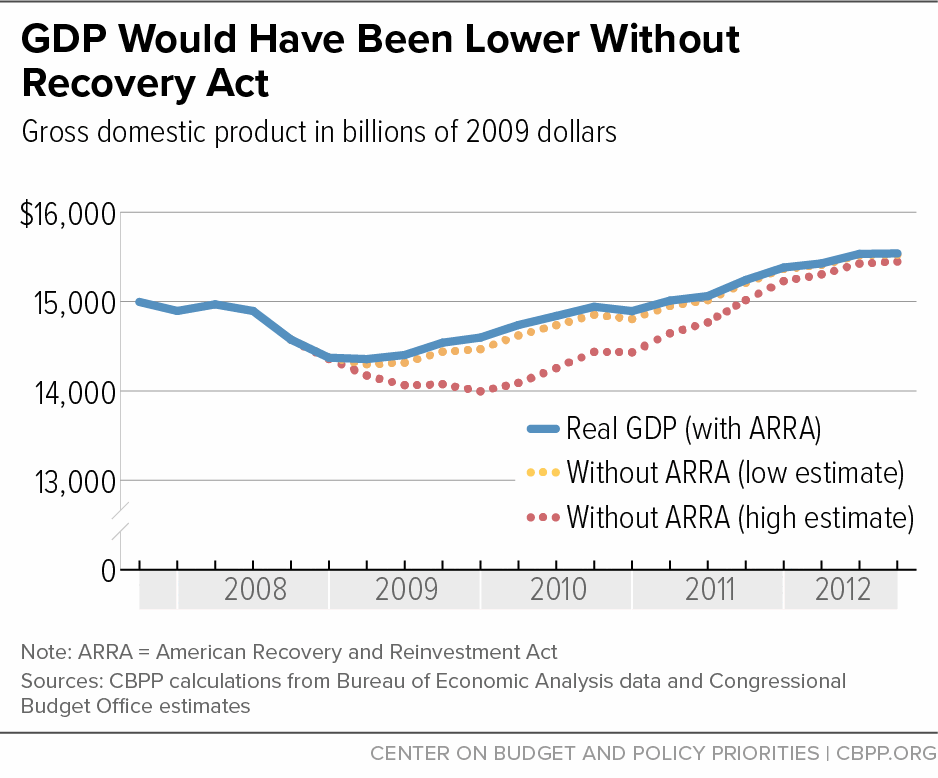

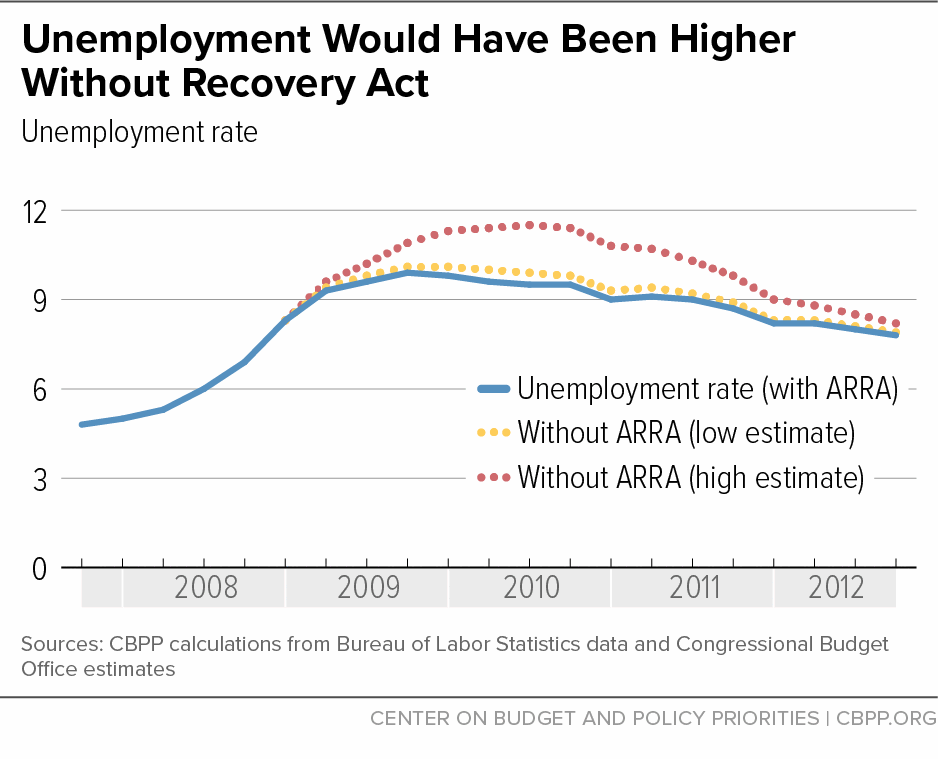

Neither TARP nor ARRA was successful politically, and not all of ARRA’s provisions — such as AMT relief — satisfied the criteria for sound stimulus. But their positive effect on financial markets and the economy was crucial to turning the economy around in 2009. Output and employment would have been significantly lower in the recession and early stages of the recovery without ARRA, according to CBO’s analysis.

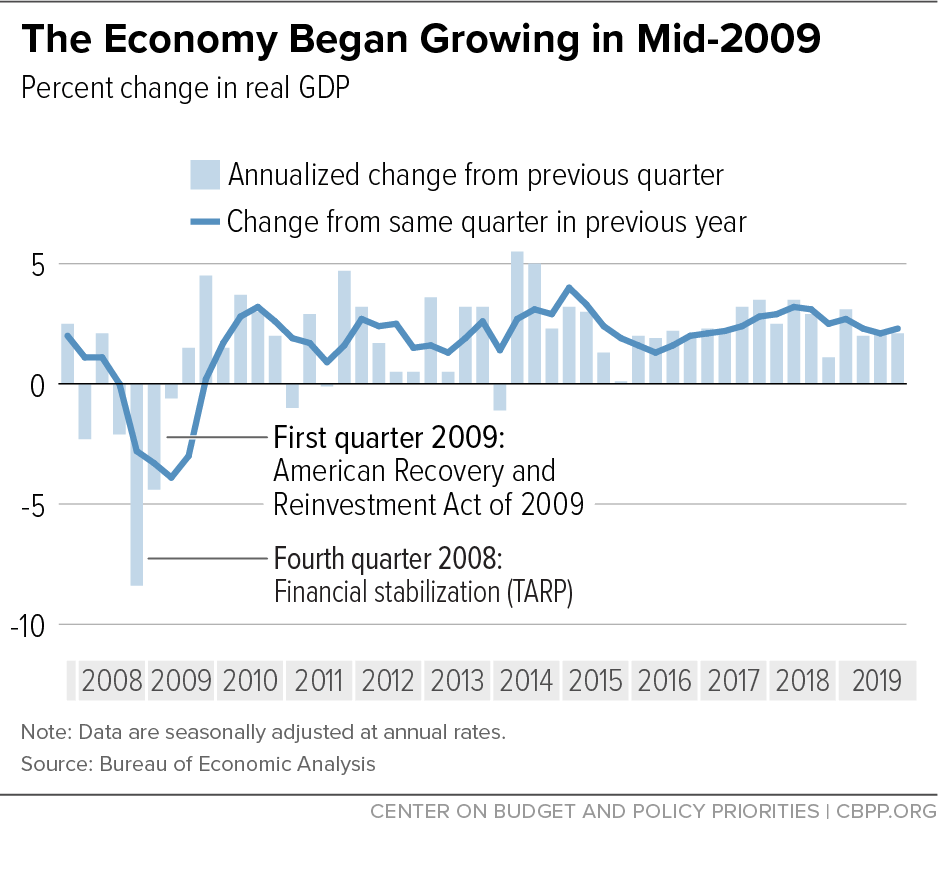

Economic activity as measured by real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) was contracting sharply when policymakers enacted TARP and ARRA (see Figure 1). The economy stopped shrinking and began growing in mid-2009, and the expansion lasted more than a decade. Job losses, which reached over three-quarters of a million a month in late 2008, began to shrink in the spring of 2009, and private-sector job growth began an unbroken string of monthly job gains from March 2010 through February 2020.

ARRA was designed to boost the demand for goods and services in order to stimulate growth and preserve jobs in the recession and to create them in the early stages of the recovery. (See box, “How ARRA Increased Output and Employment.”) GDP was higher and the unemployment rate lower each year between 2009 and 2012 than they would have been without ARRA, with the largest impact in 2010, CBO found.

GDP was between 0.7 and 4.1 percent higher in 2010 than it otherwise would have been, CBO estimated (see Figure 2). The impact faded after 2010, as ARRA stimulus wound down, but CBO estimated that even at the end of 2012, GDP was between 0.1 and 0.6 percent larger than it would have been without ARRA.

Similarly, while CBO estimated that ARRA had the greatest effect on the unemployment rate in 2010 (see Figure 3), even in the fourth quarter of 2012, the unemployment rate was 0.1 to 0.4 percentage points lower than it otherwise would have been, and employment was between roughly 100,000 and 800,000 jobs greater than it otherwise would have been.

How ARRA Increased Output and Employment

Effective economic stimulus and recovery measures work by increasing the demand for goods and services at a time when there is economic “slack” — insufficient demand to keep businesses operating at full capacity and to generate full employment. Measures that increase demand stop the destruction of jobs and begin to put people back to work during times when business and consumer confidence is low and economic activity is declining. They continue to do so in the early stages of a recovery from a recession if there is still substantial economic slack.

For the most part, ARRA was well-designed to produce stimulus as quickly as could be done. It included fast-spending, high “bang-for-the-buck”* items such as expansions in SNAP and UI — provisions that a broad range of economists and CBO rate as some of the most highly stimulative types of spending per dollar of cost. Its state fiscal relief was essential to moderate the drag on the economy from the even larger budget cuts and tax increases that states otherwise would have had to impose. The package also included infrastructure investments, which are highly stimulative once projects are underway but sometimes require significant lead time. Finally, some of the package’s tax provisions were targeted on low- and moderate-income households, such as expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, making them effective as stimulus. Various other ARRA tax provisions were less well-targeted and, according to CBO, had a far smaller stimulative effect.

CBO’s range of estimates of the percentage boost to GDP from ARRA is based on low and high estimates of the bang for the buck of the various ARRA measures. Among major provisions, these were 0.5 to 2.5 for federal purchases of goods and services, 0.4 to 2.1 for transfer payments to individuals such as SNAP and UI, and 0.3 to 1.5 for tax cuts for lower- and middle-income people. In contrast, CBO’s estimates of bang for the buck were 0.1 to 0.6 for alternative minimum tax relief for higher-income people, and 0 to 0.4 for the corporate tax provisions in ARRA, suggesting that the latter two provided little or no stimulus.

*Dollars of net new aggregate demand for goods and services stimulated per dollar of budget cost. A value above 1 means that for every dollar of cost to the Treasury, the demand for private sector goods and services increased by more than a dollar.

As discussed in the box “Keeping Recessions as Short and Shallow as Possible: Why It Matters,” the human, social, and economic costs of recessions go well beyond the value of the goods and services not produced and the income not earned, though these immediate economic losses were quite large in the Great Recession. The cumulative gap between actual GDP and CBO’s high estimate of how much lower GDP would have been without ARRA (the cumulative gap between the blue line and the red dotted line in Figure 2) was about $1.3 trillion (in 2009 dollars). By reducing job losses, ARRA saved the equivalent of 11 million full-time years of work, CBO estimated.[11]

As large, timely, and reasonably well-targeted and effective as ARRA was, a rapid and robust recovery from the Great Recession proved elusive. The output losses and jobs hole created by the Great Recession were so large that an even larger stimulus package would have been required to climb out more quickly. Indeed, the incoming Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), Christina Romer, suggested a larger package, but it was judged to be politically impractical.[12] President Obama proposed additional stimulus in subsequent budgets, but Congress agreed to only modestly more stimulus.

In a 2012 assessment of ARRA, Romer acknowledged that it was too small and could have been more effective but stated that over time, “the fiscal stimulus will be viewed as an important step at a bleak moment in our history. Not the knockout punch the administration had hoped for, but a valuable effort that improved the lives of many.”[13]

The CBO and Blinder-Zandi analyses bear out Romer’s belief that ARRA moderated the Great Recession. Jason Furman, who served as CEA chair in the second Obama term, argues based on recent fiscal stimulus research that “the tide of expert opinion” among policy-oriented economists and international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development was already shifting prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The “new view” of fiscal policy reverses most of the “old view” that prevailed leading up to the Great Recession — and still may prevail among some policymakers, notwithstanding the bipartisan and near-unanimous support for the CARES Act as a COVID-19 emergency measure.[14]

Several policy shifts distinguish this new perspective, which features the following four principles:

- Fiscal policy shouldn’t be subordinate to monetary policy. Furman argues that fiscal policy is an essential tool to support aggregate demand and should not be subordinate to monetary policy, as many considered it to be before the Great Recession. In response to COVID-19, the Fed has cut its target interest-rate range from one that was already substantially lower than before the Great Recession essentially to zero,[15] eliminating its room for conventional interest rate cuts to stimulate aggregate demand in a weakening economy. Notwithstanding the significant quantitative easing and financial-market stabilization measures the Fed is now taking, the CARES Act and other fiscal policy measures are critical for fighting a COVID-19 recession, and fiscal policy will be a necessary complement to monetary policy in any future recession.[16]

-

Fiscal policy stimulates demand in a recession. Furman argues that evidence from the Great Recession shows that discretionary fiscal policy can be highly effective at stimulating aggregate demand when the Fed does not counter it by tightening. By stimulating economic growth while interest rates are low, well-targeted, deficit-financed stimulus measures may even encourage new investment despite increasing the deficit. This suggests that CBO’s high-end estimates of ARRA’s effect on output and employment, described in the box above, are likely to be much closer to the likely stimulus effects of those measures in a recession than its low-end estimates.

Recovery from the Great Recession was slowed by a premature turn toward budget austerity beginning in 2010, when concerns about budget deficits and debt prevented policymakers from adopting further needed stimulus. Instead, the winding down of ARRA spending became a drag on growth in 2010-11, as Figure 1 shows. Congressional opposition to continuing fiscal stimulus in order to promote a stronger recovery was fueled by the emergence of small-government populist Tea Party sentiments and since-discredited academic evidence purporting to show that levels of debt beyond a 90-percent-of-GDP-threshold were damaging to growth[17] and that cutting government spending in a recession could increase growth[18] — contrary to the overwhelming evidence that cutting spending or raising taxes in a recession is contractionary.

-

Fiscal space constrains stimulus less than previously thought. Furman rejects the idea that the United States now faces a debt crisis that requires immediate austerity, noting that “fiscal stimulus is less constrained by fiscal space than previously appreciated.” Fiscal space is the amount of room a country has to increase deficits and debt without debt holders losing confidence and provoking a debt crisis with spiking interest rates, falling government bond prices, and the risk of a sharp contraction in economic activity. Furman does not call for abandoning fiscal responsibility, but even before COVID-19 created the need for an urgent and robust response, he rejected the idea that we - have, or are near to having, a debt crisis that precludes borrowing for stimulus in a recession.

Both former CBO Director Douglas Elmendorf and current CBO Director Phillip Swagel agree with that position, with Swagel stating last summer, “when there’s a financial crisis and a recession . . . countries that respond with expansionary policy do better. And it looks like the United States has the fiscal space to do that. . . . Interest rates are low. The federal government is able to borrow. So [the debt situation] is not an immediate crisis. . . . It’s a long-term challenge.”[19]

Similarly, Elmendorf wrote in the Washington Post last year, “Yes, we have a serious long-term debt problem, but no, that problem does not make anti-recessionary budget policy impossible or unwise.”[20] The fact that interest rates were at a historically low level and expected to remain so for many years even at the time he was writing last summer led Elmendorf to the following conclusion, which is even more true now:

Federal borrowing is thus less costly and creates less risk for the federal government than many of us predicted several years ago — and, according to economic analyses, does less harm to the economy even in the long run. In addition, the funds used as stimulus do not disappear: They support government spending for public goods and services, or they lower taxes so that households have more resources for their private activities.

In sum, we have plenty of capacity in the federal budget to undertake vigorous countercyclical tax and spending policies when the next recession arrives. Given the economic and social costs of recessions, we should undertake such policies (emphasis added).

-

Sustained fiscal expansion could be necessary. The low-interest-rate environment and the experience with sluggish recoveries from the Great Recession and the milder recessions in 1990-1991 and 2001 lead to the fourth principle in the new view of fiscal policy: it may be desirable to pursue sustained fiscal expansion.

Before the Great Recession, economists who were sympathetic to fiscal stimulus in principle were hesitant to recommend it in practice due to concerns that delays in recognizing the need and enacting the necessary legislation would delay the stimulus from taking effect until monetary stimulus had already kicked in and the economy was recovering at a reasonable pace. That could potentially be destabilizing and lead the Fed to raise interest rates to prevent overheating, largely offsetting the stimulus. The net result would simply be an unnecessary increase in debt to finance stimulus that was no longer needed and the Fed had largely offset.

In today’s low-interest-rate global economy, however, the case for more sustained stimulus in the face of deficient aggregate demand is much stronger, especially if the stimulus takes the form of productive investment.[21] The Great Recession wreaked long-lasting damage on the economy’s productive capacity, as a result of the sharp contraction in productive investment and the effects of long-term unemployment on workers’ skills, employment prospects, labor force participation, and earnings, as described earlier. Stronger and more sustained fiscal stimulus could have attenuated these effects substantially. Avoiding additional damage due to COVID-19 is now essential.[22]

Stimulus measures must be well-designed to stimulate aggregate demand in a cost-effective way. The principles for designing effective stimulus under the new view of fiscal policy are similar in many ways to those captured in the “timely, targeted, and temporary” catch-phrase prevalent in 2008, but they should be updated to reflect changed circumstances — including COVID-19 — and lessons learned from the Great Recession.[23]

To be most effective stimulus should be:

Implemented early. Fiscal stimulus should be implemented as early as possible in a recession. Measures like cash or SNAP payments for those in the greatest need delivered early in a recession stimulate new spending quickly, lessening the extent to which businesses cut back on production or lay off workers due to weak demand. Tax cuts that will be saved in large part rather than spent quickly, in contrast, do little to bolster demand. Increased outlays in government investment programs that spend out slowly don’t immediately boost aggregate demand, but they can be helpful in getting back to full employment more quickly, thereby reducing the human costs and preventing the harm to future growth a sluggish recovery could cause.

Well targeted. Measures targeted on individuals and entities that will quickly spend the bulk of any new resources they receive have a high bang for the buck in stimulating aggregate demand (see box, “How ARRA Increased Output and Employment”). Such individuals include unemployed workers and people of modest means, in contrast to higher-income individuals and households, who will save a large portion of any additional income.

Fiscal relief for state governments is another well-targeted form of stimulus. Faced with declining tax receipts and looming deficits when the economy slows, states respond by raising taxes and cutting back on spending, especially for health care, education, and aid to local governments. States have little alternative, since almost all are required to balance their operating budgets in bad economic years as well as good ones. But such actions further reduce demand in the economy and deepen the recession. Federal fiscal relief that enables states to minimize such spending cuts and tax increases thus helps prop up the economy in a time of weakness.

Bold in size and scope and responsive to changing conditions. Fiscal stimulus is a response to temporary weakness in the economy. The country should not be stuck with permanent, deficit-increasing tax cuts or spending increases because of a temporary economic downturn — but neither should stimulus measures be terminated prematurely, as happened with ARRA. When the economy weakens, avoiding a serious recession and its attendant social and economic costs should be policymakers’ top priority, and recent slow recoveries suggest that the costs of erring on the side of providing too much stimulus are less than the costs of providing too little — especially in today’s low-interest-rate environment.

A more robust set of automatic stabilizers would vary the size and duration of stimulus automatically in response to changing economic conditions. In a recession, however, policymakers also should be prepared to provide additional discretionary stimulus as needed.

The temporary measures enacted to fight the Great Recession added to the debt, and interest on that higher debt added modestly to future deficits, but economic stimulus played only a minor role in the rise in deficits and debt since 2001.[24] While it might be ideal in a non-crisis atmosphere to pair stimulus measures with other measures that pay for the stimulus once the economy is strong enough, the search for the latter in a politically fraught or crisis environment should not stand in the way of enacting needed stimulus to keep a recession as short and shallow as possible.

The CARES Act and other measures policymakers have taken thus far in the pandemic largely satisfy these criteria. CARES includes essential measures to respond to the public health and economic crises, though more will be needed. The CARES Act measures are in effect only for temporary periods, such as through the end of the year, and lack provisions for extending them as economic conditions warrant. They also lack key elements such as a SNAP benefit increase and an emergency fund modeled after the successful TANF Emergency Fund in place during the Great Recession. Furthermore, the increase in the federal share of state Medicaid costs provided in the previous COVID-19 response legislation is smaller than the increase provided in the Great Recession and ends at the end of the public health emergency, neither continuing nor increasing if the economy worsens.[25]

Well-designed stimulus measures should “trigger on” as early as possible and “trigger off” once a robust recovery is clearly underway. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the recognized arbiter of business-cycle dating, does not provide a determination of when a recession started until well after that date, and only after examining and comparing several measures of economic activity over many months. And, as discussed above, in recent business cycles, the formal end of a recession has been followed by an extended period of sluggish growth and persistent slack during which fiscal stimulus would still be beneficial, rather than the sharp rebound and robust recovery characteristic of most earlier post–World War II recessions.

Thus, the NBER’s dating of business-cycle peaks and troughs is not a reliable real-time indicator of when to start or end stimulus. Economist Claudia Sahm has shown, however, that a reliable early indicator that the economy is in a recession is when the three-month average unemployment rate is 0.5 percentage points higher than its level in any of the previous 12 months. That indicator has occurred early in every recession back to the 1970s and has never given a false reading indicating a recession when none has followed.

In more typical circumstances,[26] this indicator, now known as the “Sahm rule,”[27] is a good indicator for triggering on a package of stimulus measures that ideally has already been enacted and is ready to go. There also should be a trigger for turning off or phasing out such stimulus measures when, but only when, a robust recovery is underway. That trigger may be different for particular stimulus measures. In many cases, however, meeting all three of the following conditions would be a reasonable triggering off criterion:

- the three-month average unemployment rate has fallen for two straight months (in order to guard against cutting off stimulus before unemployment has peaked);

- the three-month average unemployment rate is below a specified threshold level for two straight months (so as not to cut off stimulus when unemployment is still highly elevated); and

- the three-month average unemployment rate is less than 1.5 percentage points higher than its rate when the measure was triggered on.

In the case of the CARES Act, where measures are already in place but expire by the end of the year, it is important that policymakers avoid prematurely withdrawing needed support for the economy and those facing hardship. Triggers based on economic conditions, not arbitrary calendar dates, should determine the extent and duration of stimulus measures.

To prepare for future recessions, policymakers could strengthen the existing automatic stabilizers by embedding the Sahm rule in the statutes that provide such benefits, such as by providing additional federally funded weeks of unemployment insurance, a bump in SNAP benefit levels, and an increase in the federal matching rate for state Medicaid expenditure when the Sahm-rule trigger signals that the economy is in a recession.

A core set of measures would provide effective fiscal stimulus to bolster aggregate demand and reduce economic hardship in recessions. The following discussion offers general principles for designing effective stimulus in those core areas.

One caveat: Puerto Rico participates fully in the unemployment insurance system, but instead of receiving federal funding for its nutrition assistance program sufficient to serve all eligible people who apply and having a fixed percentage of its Medicaid costs covered by the federal government, as a state would, Puerto Rico instead gets capped block grants for Medicaid and nutrition assistance that don’t rise automatically when need increases in a recession. ARRA and the CARES Act included provisions to increase assistance for Puerto Rico in the troubled periods these pieces of legislation cover, and so should subsequent stimulus packages that Congress is likely to work on in the months ahead. But Puerto Rico, whose economy has been struggling for years, has undergone the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history, and has been devastated further by recent natural disasters, ultimately needs stronger safety net programs on an ongoing basis,[28] not just accommodations in stimulus packages.

Additional measures are also likely to be needed to address challenging idiosyncratic problems associated with particular crises, such as distressed homeowners in the mortgage crisis and Great Recession[29] and, most vividly, the health care costs and income losses due to quarantines and business shutdowns in the pandemic.

Unemployment insurance provides well-targeted fiscal stimulus and scores high in bang for the buck. Substantial reforms to the UI program, however, would improve its coverage and make it a stronger fiscal stimulus measure.

States run the basic UI program, while the U.S. Department of Labor oversees the system. The basic program in most states provides up to 26 weeks of benefits to unemployed workers, replacing about half of their previous wages, up to a maximum benefit amount that each state sets. States provide most of the funding for those benefits through taxes paid by employers; the federal government pays only the administrative costs.

Although states are subject to a few federal requirements, they are generally able to set their own eligibility criteria and benefit levels. In recent years, for example, a handful of states have reduced their maximum number of weeks of regular UI benefits below 26 weeks. This has weakened the protections UI provides workers experiencing long unemployment spells and has reduced UI’s effectiveness as stimulus when the economy is weak.

UI was established in 1935 and has not adapted adequately to subsequent changes in the labor market. When UI was designed, the typical job loser was a married male breadwinner laid off from a full-time job to which he could expect to return when business picked up. But in the 21st-century labor market, the program’s outdated eligibility requirements often exclude people such as part-time workers and those who must leave work for compelling family reasons, like caring for an ill family member. This prevents large numbers of unemployed workers, many of whom are women and people of color, from receiving UI benefits.

Nor does UI respond as effectively as it could to provide additional weeks of benefits in an economic downturn, when unemployed workers are more likely to exhaust their regular state UI benefits. UI’s Extended Benefits (EB) program provides an additional 13 or 20 weeks of benefits to jobless workers who have exhausted their regular UI benefits in states where the unemployment situation has worsened dramatically (regardless of whether the national economy is in recession). The total number of weeks of EB available in a state depends on the severity of unemployment in the state and its unemployment insurance laws. Normally, the federal government and the states split the cost of EB.

When a state’s economy weakens, regular state UI caseloads expand and at some point EB may kick in, supporting unemployed workers’ and their families’ incomes and spending. In practice, however, the criteria for EB to trigger on are so stringent that federal policymakers have had to enact temporary programs providing additional weeks of UI benefits on an ad hoc basis in national recessions since the late 1970s. The temporary discretionary measures enacted in the Great Recession, for example, included extra weeks of benefits and full federal funding of EB from mid-2008 through 2013, as well as a federally funded $25 increase in weekly UI benefits in 2009-10.

As discussed earlier, the stimulus to demand from an expanding UI caseload and additional weeks of UI benefits helped prevent an even sharper drop in spending during the Great Recession and its immediate aftermath. However, temporary federal UI stimulus needed to be reauthorized periodically — which became increasingly contentious politically — and it expired at the end of 2013, even though there was still considerable unemployment and underemployment at the time and economic activity was recovering relatively slowly. In addition, out-of-date eligibility criteria and the reduction in the maximum number of weeks of regular UI benefits in some states limited the expansion of caseloads in the Great Recession and hence the amount of stimulus UI could provide.

To strengthen UI as a stimulus measure — as well as to meet UI’s primary purpose of supporting eligible workers (and their families) who’ve lost their jobs through no fault of their own — the criteria for receiving UI benefits should be modernized to reflect 21st-century labor market conditions, which would result in a larger share of the jobless receiving benefits and hence boost the total amount of automatic stimulus in a recession.

The Obama Administration’s 2017 budget proposal[30] and a collaboration among the Center for American Progress, the National Employment Law Project, and the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality[31] both provide blueprints for comprehensive reform of the UI system, including modernizing eligibility and reforming EB not only to improve protections for workers but also to strengthen the fiscal stimulus UI can provide. (These proposals also include UI solvency reforms to ensure that states build up reserves during good economic times and are better prepared to fund regular benefits when unemployment rises.)

The CARES Act provides robust changes to UI that temporarily expand eligibility and, for four months, raise benefit levels substantially, but new legislation will be required to extend these provisions beyond the current year.[32] Comprehensive UI reform that broadens eligibility and strengthens UI’s role as an automatic stabilizer is necessary to be better prepared for future recessions.

SNAP provides nutritional support for low-wage working families and unemployed individuals, low-income seniors, and people with disabilities living on fixed incomes. The federal government pays the full cost of SNAP benefits and splits the cost of administering the program with the states, which operate the program. SNAP eligibility rules and benefit levels are, for the most part, set at the federal level and uniform across the nation, though states have flexibility to tailor aspects of the program.

Like UI, SNAP benefits are spent quickly and therefore provide high bang-for-the-buck stimulus in a weak economy. SNAP caseloads also expand and contract with the level of economic activity as more people’s income falls below the income threshold for eligibility in a recession and more people’s income rises above it in an expansion.

The SNAP benefit formula targets food assistance according to need: very poor households receive larger payments than households with somewhat more income since they need more help affording an adequate diet. The benefit formula assumes that families will spend 30 percent of their disposable income for food; SNAP makes up the difference between that 30 percent contribution and the SNAP “maximum benefit,” which is set at the cost of the Thrifty Food Plan, the Agriculture Department’s estimate of a very low-cost but nutritionally adequate diet. In 2018 the typical family with children received $387 a month in SNAP benefits; a typical one-person household received $130 a month.

Some people are not eligible for SNAP regardless of how small their income and assets may be, such as striking workers, many college students, and certain immigrants with lawful immigration status. Immigrants with undocumented status also are ineligible for SNAP.

In addition, adults without a disability who are aged 18 through 49 and aren’t employed at least 20 hours a week or participating in a qualifying workfare or job training program (and don’t have dependents in the home) are limited to three months of benefits in a 36-month period. States can waive this rule in areas with high unemployment. During the Great Recession and its aftermath, that time limit was either suspended (for 2009 and 2010 under a provision of ARRA) or waived in most states due to high unemployment.

Until recently, states qualified for waivers during and immediately after a recession when UI Extended Benefits were triggered on in the state. In late 2019, however, the Trump Administration finalized an administrative rule that sharply limits such waivers, even in a recession.[33] If the new policy goes into effect, the EB criterion will no longer be allowed as a qualification for state waivers, and very few areas will qualify during economic downturns.[34]

SNAP experienced large growth during and after the Great Recession. Caseloads expanded significantly between 2007 and 2011 as the recession and sluggish economic recovery dramatically increased the number of low-income households that qualified and applied for help. In addition to the automatic stimulus from caseload growth, ARRA raised the level of maximum SNAP benefits by 13.6 percent beginning in April 2009, with the intention of keeping benefits at that new level until the value of the Thrifty Food Plan caught up through normal food-price inflation. Because of very low food price inflation (in fact, deflation in some years), the cost of the plan grew more slowly than expected and policymakers ended the supplement to benefits in November 2013. While they were in effect, these payments delivered $40 billion in high bang-for-the-buck economic stimulus on top of the increase in SNAP outlays due to the growth in caseloads.

Both a provision allowing states to seek waivers to raise SNAP benefits for some households and a suspension of the three-month time limit for unemployed adults not raising minor children are in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, but last only through the pandemic emergency period.[35] A measure to raise the maximum SNAP benefit, comparable to the ARRA provision, is still needed and should be designed to remain in effect while the economy remains weak and unemployment remains elevated. In addition, to be ready for future recessions, policymakers should enact legislation that provides for an increase in maximum SNAP benefits and suspension of the three-month time limit that would be triggered on automatically when the economy slides and then triggered off automatically when the economy recovers.

In a recession, state budget receipts fall, and rising unemployment and poverty increase the demands on state-provided services that assist people in need, including the state share of Medicaid costs. Many of the actions that states must take to achieve budget balance in the face of falling revenues — cutting services, laying off workers, and raising taxes — further weaken the economy.

Federal financial assistance to states can mitigate these effects. Direct federal grants to states can provide fiscal relief in a recession that helps states meet their balanced budget requirements without having to go as far in enacting contractionary policies that lengthen and deepen the recession. The approach taken in the last two recessions included, as one of the key fiscal relief measures, temporarily increasing the federal government’s share of the costs that states incur in operating Medicaid, the public insurance program that provides health coverage to low-income families and individuals.

Medicaid is funded jointly by the federal government and the states. Each state operates its own Medicaid program within federal guidelines. Because the federal guidelines are broad, states have a great deal of flexibility in designing and administering their programs. As a result, Medicaid eligibility and benefits can and often do vary widely from state to state. States are guaranteed federal Medicaid matching funds for the costs of covered services furnished to eligible individuals, but states have relatively broad discretion to determine who is eligible, what services they will cover, and what they will pay for covered services.

The federal government contributes at least a dollar in matching funds for every dollar a state spends on Medicaid. The fixed percentage that the federal government pays, known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), varies by state, with the federal government shouldering a larger share of the costs in poorer states than in wealthier ones. In the poorest state, the federal government pays well over 70 percent of Medicaid service costs. In addition, the federal government pays 90 percent of the costs for care provided under the Medicaid expansion provision of the Affordable Care Act in states that have adopted the expansion. The federal share of Medicaid expenses used to be about 57 percent overall in a typical year but has increased to over 60 percent with the expansion.[36]

In the 2001 downturn, Congress gave $20 billion in fiscal relief to the states, half in the form of enhanced Medicaid matching rates and half in a block grant distributed among the states on a per-capita basis. That relief was not enacted until May 2003, however, more than two years after the start of the recession, by which time virtually all states were experiencing budget deficits. That delay reduced the effectiveness of the fiscal relief in averting cuts in vital programs such as Medicaid and education and in lessening the adverse effects that such state budget actions were having on the economy.

State fiscal relief in the Great Recession was enacted more quickly as part of ARRA. That relief included an increase in the Medicaid FMAP and a “State Fiscal Stabilization Fund” that provided two block grants for states — a $39.5-billion grant earmarked for education and an $8.8-billion grant to help fund other key services. States could use the flexible block grants to avert budget cuts in education or other basic state services, such as public safety and law enforcement, services for the elderly and people with disabilities, and child care. Those funds could also be used for school modernization, renovation, or repair.

The CARES Act contains significant new resources to help states address massive budget problems due to COVID-19, though states will need more aid in coming months.[37] The FMAP increase in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act lasts only through the health emergency period. A larger increase in the FMAP of longer duration, as well as a more robust stabilization fund, are necessary.[38] In addition, to be ready for future recessions, policymakers should enact legislation that provides for an increase in the FMAP and a stabilization fund that would be triggered on automatically in a national recession and for states experiencing high unemployment when there is not a national recession.

Stimulus Payments to Individuals and Families

Direct cash assistance to low- and moderate-income households is one of the most well targeted stimulus measures because it goes to people who will quickly spend almost all of any additional income they receive, generating high bang for the buck. Either one-time, lump-sum payments or a refundable tax credit (under which taxpayers whose tax liability is less than the amount of the credit receive a cash payment for the difference) are suitable delivery mechanisms for a large share of the population. Low-income people not required to file a tax return can be identified if they are receiving benefits such as Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, or veterans’ benefits that are administered by the federal government, and likely also if they receive benefits administered through state social service agencies. In addition to its role in providing stimulus, direct cash assistance for low- and moderate-income households directly addresses the human costs of recessions by helping ensure that individuals and families have enough income to meet basic needs in particularly tough times.

In theory, temporary middle-class tax cuts are less stimulative because recipients are less cash constrained and are not likely to change their consumption dramatically in response to a temporary increase in income, although some evidence suggests one-time cash rebates may stimulate one-time purchases of, or be used as a down payment for, big-ticket items such as new appliances or a car. Temporary tax cuts for high-income taxpayers have little bang for the buck because high-income taxpayers are least likely to increase their spending substantially in response to a temporary boost to their income.

The Economic Stimulus Act, enacted in February 2008, delivered one-time income tax rebates and payments to tax filers who had at least $3,000 in earnings in 2007 or 2008, and to people who received Social Security benefits or veterans’ payments. These rebates were phased out for high-income taxpayers. ARRA then followed with a “Making Work Pay” refundable tax credit for the 2009 and 2010 tax years, in the form of reduced income-tax withholding over the course of the year, although the saliency of the tax cut to many taxpayers seems to have been less than if they had received it as a lump sum payment. The Making Work Pay tax credit was replaced in 2011 and 2012 by a 2-percentage-point cut in the payroll tax, which delivers stimulus in a less well targeted way than does a refundable credit.

ARRA also made temporary changes to the Child Tax Credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), both refundable credits.[39] The changes lowered the earnings threshold for the Child Tax Credit from $12,550 to $3,000, which enabled families with earnings in that range to receive a partial credit and many other low-income families to receive a larger credit. This change was well targeted at families with low earnings who were most likely to spend the additional funds. The EITC is designed to reach individuals of modest means, so expansions of it during a recession generate high bang for the buck. ARRA increased the EITC for families with three or more children and provided a larger tax credit to married couples, which lessened marriage penalties.

Expansions of the Child Tax Credit and EITC to respond to an economic downturn can be further tailored to reach the lowest-income individuals, enhancing these measures’ effectiveness as stimulus. Making the full $2,000-per-child Child Tax Credit available to families without requiring them to meet a minimum earnings threshold would enable the credit to reach families with very low or no earnings, who have the highest likelihood of spending the funds quickly but who currently receive only a partial Child Tax Credit or no credit at all, due to their very low income. In addition, increasing the EITC for workers without children at home would reach substantially more low-income workers, who are particularly susceptible to losing income during recessions such as by having their hours reduced or losing part-time jobs as businesses cut back.

The stimulus payments in the CARES Act are available to low- and moderate-income households, including those without earnings and those that do not file tax returns. But the Act left out key groups, including many immigrants, large numbers of whom are on the front lines in the COVID-19 pandemic delivering food, providing health care services, and caring for the elderly. The CARES Act also didn’t provide sufficient direction to ensure that Treasury will use all existing means to get these payments to eligible households automatically rather than requiring them to file tax returns.[40] The Treasury should aggressively use the authority the CARES Act provides, and any upcoming legislation should fill the holes and improve delivery.

A recession heightens the importance of improvements in and further expansions of eligibility for the Child Tax Credit and EITC, especially for the lowest-income workers and families currently left out of the full credits. Such improvements would deliver high bang-for-the-buck stimulus and, if made permanent, also could strengthen these credits’ role as automatic stabilizers.

Emergency Cash Assistance and Subsidized Jobs

The number of people facing deep economic insecurity because they are unable to find steady work rises in a recession. Many of these people normally don’t qualify for unemployment insurance, which over the past decade reached less than 30 percent of the unemployed. And while the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program can provide cash assistance to families with children with very low incomes, TANF is a fixed block grant whose resources fail to expand in a recession despite rising need. Moreover, TANF benefits in most states are very low and have eroded substantially in value over time.[41]

Policymakers should be ready to address the rising number of people facing deep economic insecurity in a recession by designing a program that supplements TANF with additional grants to states to help address emergent and ongoing basic needs of low-income households, especially those facing financial crisis. Ideally, such a program would be enacted and ready to go when triggered on by the Sahm rule and then be triggered off in the same way that UI Extended Benefits would be. Unlike TANF, which is limited to families with children, this assistance should also be available to other low-income individuals who otherwise meet the state’s TANF eligibility criteria.

The TANF Emergency Fund in ARRA provided funding that states could use in 2009 and 2010 to deliver cash assistance to help families meet basic needs, provide emergency assistance to help avert family crises, and create subsidized jobs for both parents and youth. The flexibility afforded states allowed them to quickly deploy resources to families, reducing harm that might otherwise have occurred. A signature feature of the fund was its subsidized jobs program, which an assessment found succeeded in engaging the private sector in creating meaningful employment for large numbers of individuals who would otherwise have been unemployed. It showed that “unemployed individuals in large numbers will seize the opportunity to work when given a paying job.”[42]

Together, an emergency cash assistance fund and a subsidized jobs program would provide needed income support to populations with limited assets and labor market prospects in a recession and stimulate economic activity in their local economies.

The CARES Act does not include anything akin to the TANF Emergency Fund in ARRA, leaving it up to states to fund any additional assistance that families and individuals may need to meet their basic needs, which only a few states have done. Some families and individuals in need of ongoing assistance will be helped by the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance benefits in the CARES Act or the expansion of grants to address and prevent homelessness, but many others will not. For the future, emergency assistance and subsidized jobs measures should be ready in advance to go into effect when the Sahm rule indicates a recession is under way.

People experiencing homelessness are at greater risk of contracting illnesses. They struggle to address chronic health conditions and experience worse mental health, exacerbated by the stress and trauma of being without a home. Families with children who are without a home face additional challenges ensuring that their children regularly attend school, have a safe place to do homework, can access nutritional meals, and receive needed health services.

Recessions lead to increased risks of evictions and homelessness. Measures that help people remain housed and safe moderate the increase in human hardship and suffering. They also provide stimulus by enabling those at risk of losing their housing to spend more of their income on other basic needs.

In the Great Recession, ARRA’s Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program (HPRP) was important in helping very poor families who were homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. Despite lacking adequate administrative infrastructure in many places when it was enacted, HPRP drew on $1.5 billion to serve about 1.15 million people in about 470,000 households between July 2009 and September 2011. Communities’ infrastructure for providing homelessness prevention and rapid re-housing assistance is now more established, and they could ramp up in times of need and scale down during better times if provided the federal resources to do so.[43]

While an increase in HPRP-type assistance should help in a recession, a major 2015 study from the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that Housing Choice Vouchers[44] are the most effective tool to help homeless families with children find and keep stable housing.[45] More than 5 million people in 2.2 million families with low incomes use vouchers to help pay for housing in the private market. The program is federally funded but run by a network of about 2,150 state and local housing agencies. Only 1 in 4 eligible households use housing vouchers, however, because of inadequate funding.[46]

Housing agencies have the administrative capacity to quickly and effectively extend rental assistance to more families and the expertise to inspect housing to ensure that it meets basic health and safety standards. They are also able to target assistance to those with the most urgent needs, such as people who are experiencing or at high risk of homelessness. With additional funding, housing agencies could increase the availability of vouchers in a recession when many more families experience temporary homelessness and housing instability and return to pre-recession levels when the economy improves. The amount and duration of such temporary increases should be tied to economic conditions.

The CARES Act contains important new investments in programs to serve people experiencing homelessness and to prevent people from losing their housing, but considerably more is needed.[47] An anti-recessionary increase in housing vouchers along with an increase in funds to address emergency housing needs should be in further COVID-19 responses. To be ready for the next recession, policymakers can enact legislation with triggers that automatically increases the number of vouchers when the economy weakens.

The long economic expansion following the Great Recession lulled many policymakers into unwarranted complacency about the need to prepare for the next recession. The COVID-19 pandemic has produced a rude awakening, just as the financial crisis and Great Recession did a dozen years ago. This time, however, important lessons from the Great Recession about the effectiveness of fiscal policy in keeping an economic crisis from becoming even more severe should guide our responses.