Some 1.4 million people living in Puerto Rico — about 44 percent of its population — have incomes below the poverty line, and almost half of the Commonwealth’s residents receive health coverage through Medicaid. But temporary federal funding that supplements Puerto Rico’s inadequate federal Medicaid block grant will expire soon, putting health care coverage at risk for hundreds of thousands of Commonwealth residents.

A key part of the problem is that Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program differs significantly from state Medicaid programs in ways that make it much harder for Puerto Rico to ensure that its residents, who are U.S. citizens, can get the health care they need:

- States receive open-ended federal funds to match a specified percentage of their expenditures for Medicaid-covered health services that their enrollees receive. Puerto Rico, however, is treated differently. It (like the other territories) receives only a fixed block grant funding amount each year that does not come close to covering the costs of health care for its Medicaid enrollees. Once the block grant funding is exhausted, Puerto Rico must use its own funds to pay the entire remaining cost of Medicaid health care services.

- In the states, the percentage of Medicaid costs that the federal government covers is based on a state’s per capita income relative to that of the nation as a whole. If Puerto Rico’s federal matching rate were determined using the same formula as is applied to the states, its federal Medicaid matching rate would be 83 percent. Instead, Puerto Rico draws down its federal block grant funds at a far lower matching rate set in statute at 55 percent. And because the amount of federal block grant funding that Puerto Rico receives is so small, there are periods of the year when no federal matching funds are available, because the block grant funds have been exhausted. As a result, Puerto Rico’s effective matching rate — that is, the share of its total costs for Medicaid-covered services that the federal funds defray — has been as low in some years as 15 to 20 percent.

- Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program also isn’t subject to the same eligibility and benefit standards as state programs. Puerto Rico’s Medicaid income eligibility limits are well below those in the states, so Medicaid is not available to many people in Puerto Rico who would be eligible if they resided on the mainland. Further, Puerto Rico doesn’t cover all the health services that the states must cover, including care in nursing homes, home health services, non-emergency medical transportation, and the full range of benefits for children that are guaranteed by Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment benefit. Puerto Rico also covers fewer prescription drugs than the states.

As a result of these disparities and Puerto Rico’s own fiscal constraints, Medicaid expenditures per enrollee are far less in Puerto Rico than in any state — roughly two-thirds of the lowest spending state and about one-third of the median state. (See Figure 1, which provides cost projections from the congressionally chartered Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.) On top of that, payment rates to providers are well below those in the states, which has contributed to a severe shortage of various types of health care providers on the island.

Congress provided additional federal funds to Puerto Rico in 2010 in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in 2017, and again in 2018 after Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck. But most of these federal funds expire on September 30, 2019, with a small amount available through December 31. After that Puerto Rico’s only federal Medicaid funding for fiscal year 2020 would be its block grant, which would be exhausted by March or April 2020. Policymakers consequently should work toward eliminating the sharp disparities in Medicaid funding for Puerto Rico and should act in the coming months to commit the federal funds that Puerto Rico needs to ensure continued coverage and access to care for the large share of Puerto Ricans who rely on Medicaid.

About 44 percent of Puerto Rico residents had incomes below the poverty line in 2017, compared to about 12 percent for the states.[1] Puerto Rico’s population is also older than that of the states, and its adults have higher rates of asthma, diabetes, and hypertension. Over 35 percent of adults in Puerto Rico reported they were in fair or poor health in 2014 compared to just under 18 percent in the states.[2] Despite these challenges, over 90 percent of people in Puerto Rico are insured, in large part because Medicaid covers about 45 percent of Puerto Rico’s residents.

Medicaid carries this heavy load even though Puerto Rico’s federal block grant doesn’t come close to what is needed to finance the program adequately. The block grant for fiscal year 2019 is just $367 million, while Puerto Rico’s total Medicaid expenditures are projected to be almost $2.8 billion.[3] Since 2011 Puerto Rico has received additional federal funds to supplement its inadequate block grant:

- The ACA made $5.4 billion available from July 2011 to September 2019, and an additional $925 million available through December 2019 at the 55 percent match rate;[4]

- In 2017 Congress added $295.9 million to the ACA funds available through September 2019; and

- After Hurricanes Maria and Irma devastated the island in September 2017, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 made $4.8 billion available from January 2018 through September 2019 at a 100 percent federal matching rate.[5]

Most of these funds, however, have now been spent, and the remaining funds will mostly expire by September 30, with a modest amount remaining through December.

Puerto Rico’s ability to sustain its Medicaid program is also affected by its ongoing fiscal crisis and bankruptcy proceedings. In 2016 Congress enacted the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which established the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB) to oversee Puerto Rico’s finances and restructuring of its debt. The FOMB and Puerto Rico’s government develop five-year fiscal plans, which the FOMB then certifies, that serve as blueprints for annual budgets and long-term economic projections.

Over the past three years, the fiscal plans have assumed deep cuts in Medicaid. Most recently on March 15 of this year, the FOMB rejected the governor’s March 11 proposed plan because it didn’t include what the FOMB regarded as sufficiently large cuts to meet fiscal goals. In a March 27 letter to the FOMB submitting a revised fiscal plan, the governor declined to include the full Medicaid cuts the board had outlined because they would require major reductions in coverage. The letter stated, “Absent a dramatic reduction in the number of lives participating in the program … total program expenditures cannot be reasonably expected to be lower than the revised expenditures indicated” in the revised plan.[6] The governor’s revised plan continues to assume additional federal funds beyond this year, which the FOMB does not include in its projections.[7]

These factors — inadequate and uncertain federal funds, a poorer and sicker population, and a debt crisis — all contributed to the longstanding pressures on Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program. Then in September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit, causing widespread devastation. The health impacts of the hurricanes continue to affect large numbers of Puerto Ricans. The hurricanes significantly increased the need for mental and physical health care and exacerbated health care provider shortages that were already a severe problem before the storms. Twenty-two percent of residents surveyed reported that they or a family member received or needed mental health services following Hurricane Maria. A large share (41 percent) of those with a chronic condition or disability or with a family member who has such a condition said that their condition worsened, or a new condition appeared after the storm.[8]

Maintaining the status quo is not sufficient. Puerto Rico needs to raise its very low provider payment rates that are inducing more health care professionals to leave for the mainland. It also needs to cover necessary health services and treatments that it fails to cover now, such as life-saving drugs to address Hepatitis C, and to address the effects of other changes that are causing some people to lose Medicaid eligibility despite having quite low incomes. To do so, it needs additional federal funding.

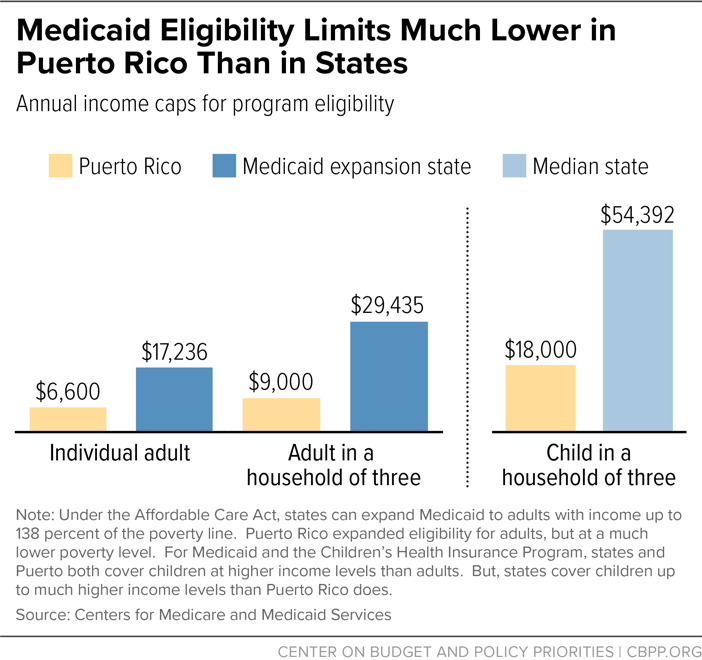

Adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line are eligible for Medicaid in states that have taken up Medicaid expansion. While Puerto Rico has expanded its Medicaid program to cover low-income adults, it bases eligibility on a local poverty line that is only about 40 percent of the federal poverty line and that has not been updated to reflect inflation since 1998.[9] This means that Puerto Rico’s program caps eligibility for individuals at $6,600 a year in 2019 and for a family of three at $9,000, compared to $17,236 and $29,435, respectively, in states that have expanded Medicaid. Eligibility for children in Puerto Rico is capped at $18,000 for a child in a family of three (twice the level for adults) but still much lower than eligibility levels for children elsewhere in the United States.[10] (See Figure 2.)

(These comparisons take into account both Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program [CHIP]. Of the 1.5 million Medicaid enrollees in Puerto Rico, coverage for about 90,000 children is financed through CHIP. An additional 150,000 people are enrolled in the Commonwealth Plan, which covers people who have incomes below 200 percent of the Puerto Rico poverty line but aren’t eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, and is paid for solely by the Commonwealth.[11])

Over the last year Puerto Rico has seen a large decrease in Medicaid enrollees. While some of the decline is likely due to people leaving the island after the hurricanes, it is also due in part to a change in how eligibility is determined. Previously, Puerto Rico’s exceptionally low eligibility levels were partially offset by certain deductions from income it allowed. Recently, Puerto Rico transitioned to a new system of determining eligibility based on modified adjusted gross income. This change, mandated nationwide by the ACA, simplifies eligibility determinations but has had unintended consequences in Puerto Rico, causing many people who were previously eligible to lose coverage even though their incomes have not changed.[12] Puerto Rico needs to increase its low eligibility limits to ensure that the new methodology doesn’t continue to cause very low-income people to lose coverage.

In addition to having lower eligibility levels, Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program covers fewer health services than do the Medicaid programs in the states. It doesn’t cover long-term services and supports, non-emergency medical transportation, or the full range of benefits for children guaranteed by the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment program.[13] It also isn’t subject to the federal Medicaid drug rebate program, and as a result (unlike the states) it does not have to cover all prescription drugs made by manufacturers who provide the federally required rebates. Among the drugs that Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program fails to provide at all are drugs to treat Hepatitis C.

An analysis by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) found that Puerto Rico spends less overall — and receives less federal funding per enrollee — than any state and far less than the median (or typical) state. Puerto Rico is projected to spend $2,144 per full-year enrollee in fiscal year 2020 compared to $3,342 for the lowest-spending state and $6,673 for the median state.[14]

Five managed care companies provide all Medicaid services in Puerto Rico, and they do so throughout the island, a significant change from before 2018 when each managed care plan was assigned a specific region. Payment rates to the managed care companies are significantly below those in the states, and plans are held accountable for spending no less than 92 percent of the Medicaid funds they receive on health care rather than administrative costs and profit. Because costs are fixed for prescription drugs, equipment, and other non-labor costs, payment rates to physicians are extremely low, reportedly as low as $10 per visit.[15]

This low provider reimbursement has likely contributed to a marked shortage of health care providers, which existed even before Hurricanes Irma and Maria. In 2015, some 500 physicians reportedly left the island, and in 2014 an estimated 2,132 health professionals left, comprising 4 percent of health care practitioners and those in related technical occupations.[16] The average annual earnings of family physicians and general practitioners in Puerto Rico are $86,970, compared to $211,780 nationally, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data for May 2018.[17] This vast disparity in earnings has contributed to an ongoing exodus of younger doctors, which has left the island with an older, shrinking physician workforce. Only 4 percent of doctors in Puerto Rico are 35 years old or younger, compared to 24 percent in the states, according to data presented to MACPAC, which leaves the island at risk of further loss of physicians as older doctors retire.[18]

Puerto Rico also has a shortage of specialty physicians. Puerto Rico had less than half the number per capita of emergency physicians, neurosurgeons, and ear, nose, and throat specialists, among other specialties.[19] Endocrinologists are also in short supply, which causes long wait times for diabetes patients.[20]

Inadequate Funding and Uncertainty Prevent Program Improvement

If Congress doesn’t provide additional federal funds to Puerto Rico, the Commonwealth will be left next year with just its highly inadequate fiscal year 2020 block grant and a small amount of federal ACA funds that are available through the end of December. These funds will run out as soon as March 2020, leaving Puerto Rico without any federal Medicaid funds throughout the remainder of the 2020 fiscal year.

Puerto Rico’s governor testified before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee that a congressional failure to act would threaten access to health care for hundreds of thousands of children, seniors, people with disabilities, and pregnant women. He also highlighted the uncertainty that the “Medicaid cliff” creates for health care providers and others involved in delivering care.[21]

As noted, the Financial Oversight and Management Board bases its fiscal planning related to Medicaid on just the small, existing block grant, because it won’t consider federal funds that Congress and the President have not already appropriated for any year covered by the five-year financial plans that guide Puerto Rico’s spending. Based on these funding assumptions, the FOMB is pushing the Commonwealth to institute large, harmful cuts to its Medicaid program over the next five years, which would exacerbate the problems in delivering health services the Commonwealth already faces. Moreover, Puerto Rico cannot take steps to shore up its Medicaid program — by increasing provider payments, covering benefits such as Hepatitis C drugs, and increasing its very low eligibility limits — without certainty that adequate funding levels will last over the long term.

Accordingly, federal policymakers should work towards eliminating the disparities in Medicaid funding for Puerto Rico and should commit the federal funds the Commonwealth needs to ensure coverage and access to care for the 1.5 million Puerto Ricans who rely on Medicaid. Puerto Rico badly needs federal funding beyond its current block grant amounts, and at a more reasonable matching rate that recognizes the island’s economic and fiscal realities. Increased federal funds are needed not just to sustain Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program at its current level, but also to raise provider payments to halt the alarming exodus of doctors and health care professionals as well as to ensure that Puerto Ricans — who are U.S. citizens — have access to health care services comparable to what they would receive if they lived on the mainland. Puerto Rico also needs to raise its Medicaid eligibility limits to stem the loss of coverage that has been an unintended consequence of the transition to federally mandated rules on how to measure household income, and to bring its eligibility levels closer to those in the states.