In the wake of a historic pandemic that created enormous economic dislocation, the economy made a much stronger and faster recovery than anticipated. The speed and strength of the recovery through 2021 were due in no small measure to a strong and unprecedented policy response that both relieved hardship and stimulated economic activity and job creation.[1] High inflation in 2022 caused the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy aggressively, raising concerns that this would cause a recession. But the latest inflation data have been very encouraging, and recession fears have receded.

Concern that the economy was on the verge of a recession grew widespread after economic growth faltered in the first half of 2022 and the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to address inflation.[2] But halfway through 2023 the economy continued to grow, unemployment remained low, and employers continued to add jobs at a high rate, even as the Fed raised its policy interest rate[3] by 5 percentage points between March 2022 and May 2023.

Inflation has fallen over the course of 2023, with both the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditure inflation measure running at or close to the Fed’s targets in recent months, though more data will be needed before we can be confident that this reflects a new and lasting trend.

After pausing in June, the Fed raised its policy rate another quarter point in July. While Fed tightening has affected interest-rate-sensitive economic activity like housing construction and slowed GDP and employment growth (as intended), the economy continues to dodge a recession, which often follows from Fed tightening. As the Fed stated in July, “Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace. Job gains have been robust in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low.”[4] But, it added that in its view, “[i]nflation remains elevated.” The Fed’s concern is based on measures of underlying “core” inflation, discussed below, that exclude volatile items like food and energy and remain higher than the Fed would like.

Although inflation has fallen substantially in the last 12 months and the Fed has not laid out a specific plan for further rate hikes, Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated at his post-meeting press conference that further rate hikes were not being ruled out. The Fed should carefully consider, however, that further tightening puts at risk the employment gains workers — especially Black workers — have achieved in the rapid recovery from the pandemic recession. The Fed will have two more months of inflation data before its next meeting. If those data show ongoing progress, the case against further tightening will be strong.

The following sections expand on these developments through June, the latest available data.

Economic Activity Expanding at Moderate Pace

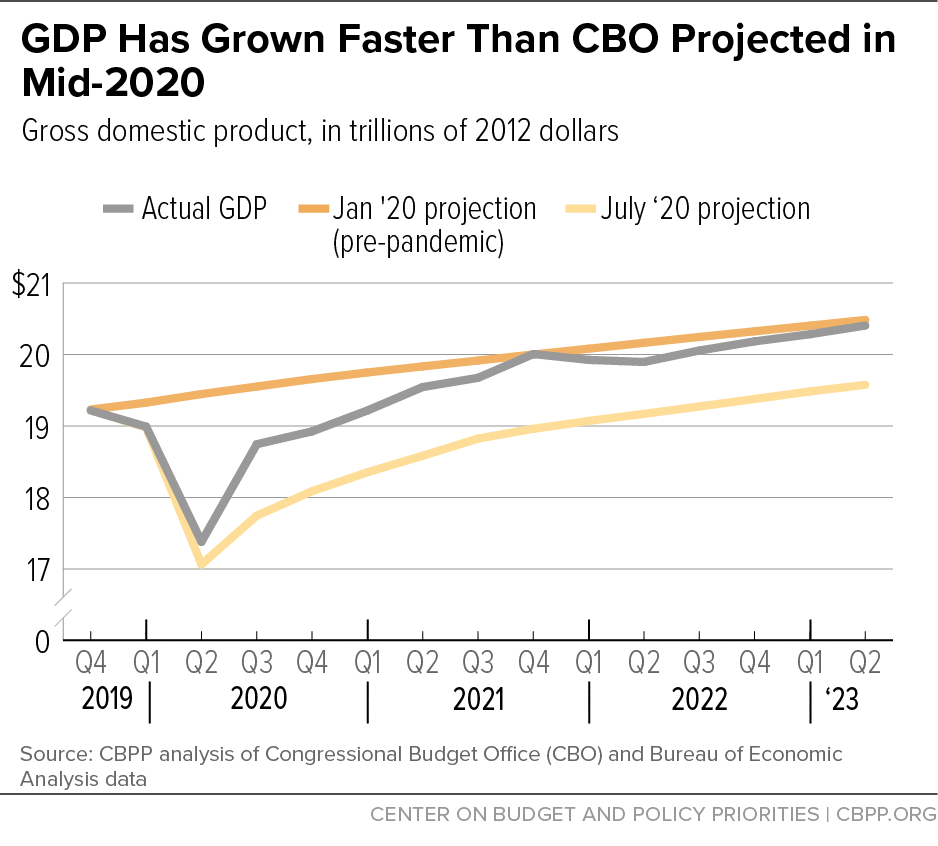

The economy rebounded strongly from the COVID-19 pandemic recession. In the fourth quarter of 2021, real GDP was essentially back to the level the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected in January 2020 and well above CBO’s July 2020 projections. (See Figure 1.) Real GDP growth slowed as the Fed began tightening in early 2022, but growth in the first half of 2023 has put GDP close to pre-pandemic projections and moderately higher than before the Fed began tightening.

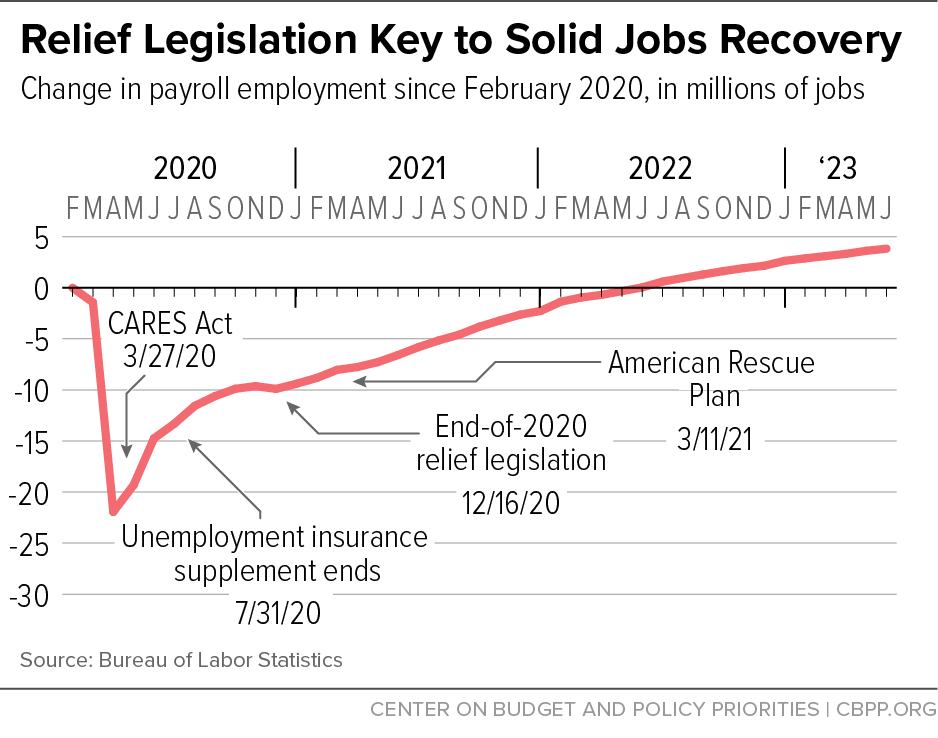

Relief legislation enacted in 2020-21 and the reopening of the economy propelled a strong jobs recovery following the pandemic recession. (See Figure 2.) Strong job growth continued through 2022 when 4.8 million jobs (an average of 399,000 per month) were added, erasing the pandemic jobs deficit.

Solid job growth has continued in 2023. Total employment (private plus government) was 3.8 million jobs higher in June 2023 than in February 2020, and private employment was 4.0 million jobs higher. This put payroll employment 1.1 million jobs higher than in CBO’s pre-pandemic projection.

The pace of job creation was a robust 278,000 jobs a month in the first half of the year, although it slipped to a still solid 244,000 in the three months ending in June. Job creation has slowed since the Fed began raising interest rates and the economy has gotten closer to full employment, but payroll job growth is still well above the rate needed for employment to simply keep up with working-age population growth.[5] The strong job growth has been paired with increases in labor force participation.

Unemployment Remains Low, Benefiting Workers Generally but Especially Black and Hispanic Workers

The unemployment rate has been under 4 percent since February 2022. It has ranged between 3.4 and 3.8 percent over the last 17 months and was 3.7 percent in June, which is in the same range as the 3.5 percent rate in February 2020 just prior to the onset of the pandemic. Moreover, the labor force participation rate (share of the population working or actively looking for work) and employment-to-population ratio (share of the population with a job) for the 25- to 54-year-old prime-age population have surpassed their February 2020 rates.[6]

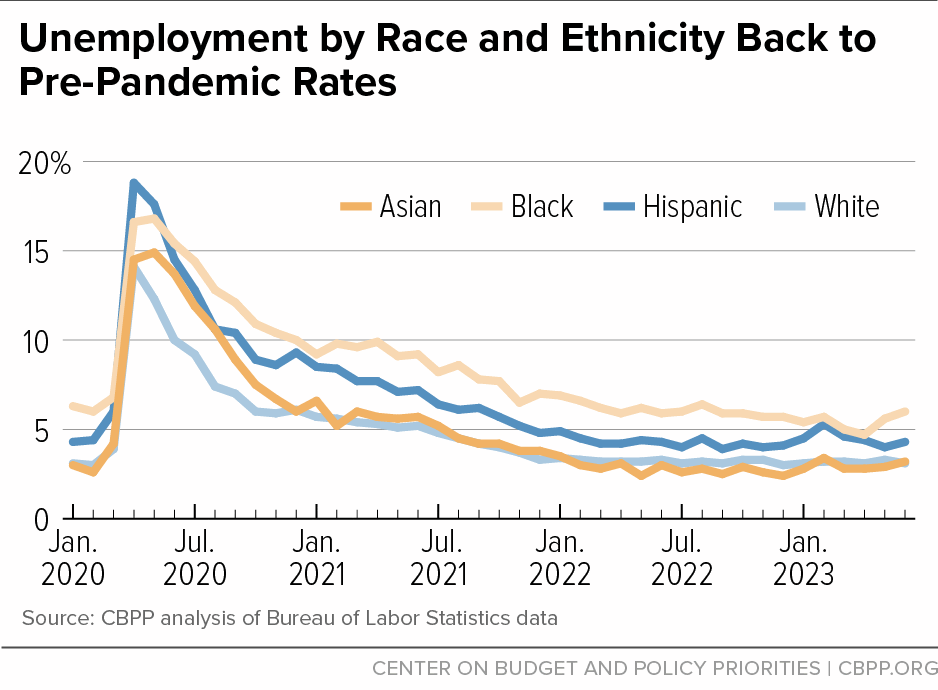

Notably, unemployment rates for Black, Hispanic, Asian, and white workers are all back in the neighborhood of their February 2020 pre-pandemic rates, which themselves were historically low. (See Figure 3 and Table 1.)

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

|

| | February 2020 | June 2023 |

|---|

| White | 3.0% | 3.1% |

| Black | 6.0% | 6.0% |

| Hispanic | 4.4% | 4.3% |

| Asian | 2.6% | 3.2% |

Black and Hispanic women aged 25-54 and in their prime working years, who had particularly large job losses in the recession, have made up all the ground lost, and their employment, labor force participation rate, and employment-to-population ratio in June were all higher than in February 2020. Immigration flows have also rebounded from their depressed pandemic levels, boosting foreign-born employment. These gains have contributed to meeting employers’ demand for workers.

However, Black and Hispanic unemployment rates are consistently higher than white and Asian rates, rise more in recessions, and come down more slowly in recoveries. That pattern was evident in the pandemic recession and subsequent recovery.

The Fed continues to anticipate a modest rise in the unemployment rate as the effects of tighter monetary policy work their way through the economy. This could put the employment gains of Black workers in particular at risk, as they are typically the first fired in a recession and the last hired in a recovery — a key reason that the Fed should be cautious as it considers further rate hikes even as inflation is trending lower.

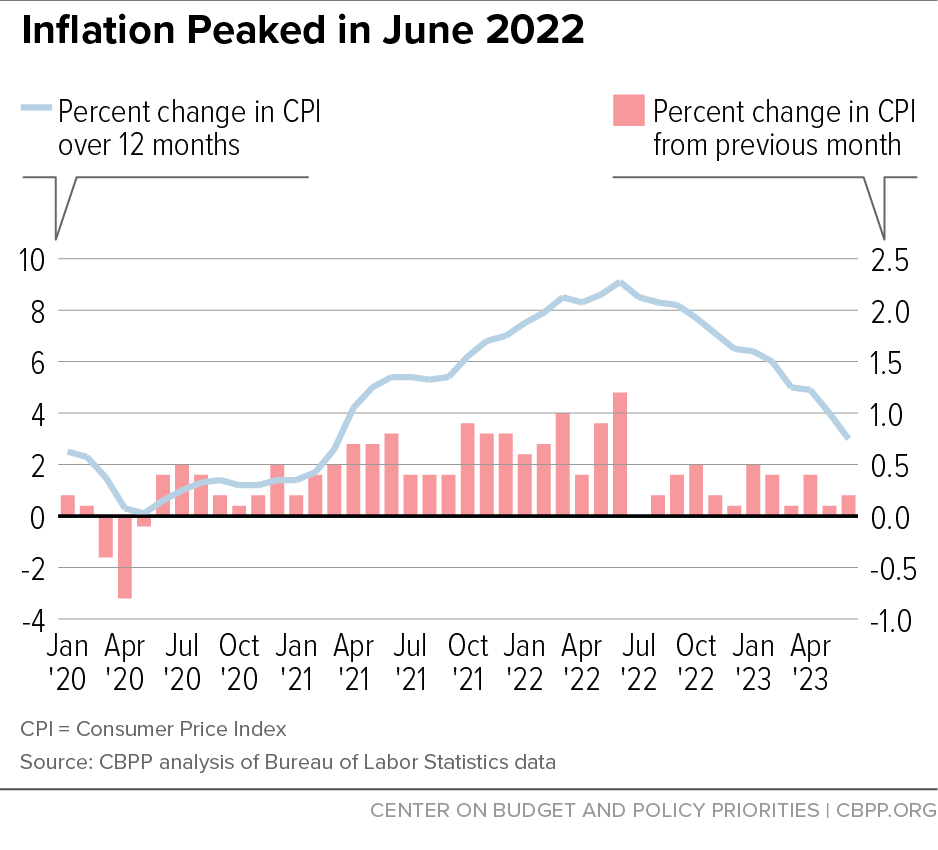

Inflation has come down significantly from its 2022 peak. Headline CPI inflation (the increase in the Consumer Price Index from the same month a year earlier) peaked at 9.1 percent in June 2022 but was down to 3.0 percent in June 2023. The monthly percentage change in the CPI has been much smaller since June 2022 than it was in the first half of that year, and the CPI over the three months ending in June was 2.7 percent. (See Figure 4.)

The Fed’s 2 percent inflation target applies to the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE), which historically has grown more slowly than the CPI.[7] Twelve-month PCE inflation peaked at 7.0 percent in June 2022 but was down to 3.0 percent in June 2023; over the six months ending in June, the PCE price index rose at a 3.3 percent annual rate, but over the three months ending in June, it rose at a 2.5 percent annual rate. The Fed wants to get the PCE all the way down to 2 percent to preserve its credibility on inflation, although many analysts think that inflation modestly higher than 2 percent could have advantages.[8]

Volatile food and energy prices have had a noticeable effect on inflation. To assess underlying (or “core”) inflation, analysts and the Fed prefer to look at the price index for all items less food and energy. For consumers, of course, it is overall inflation that affects their purchasing power.

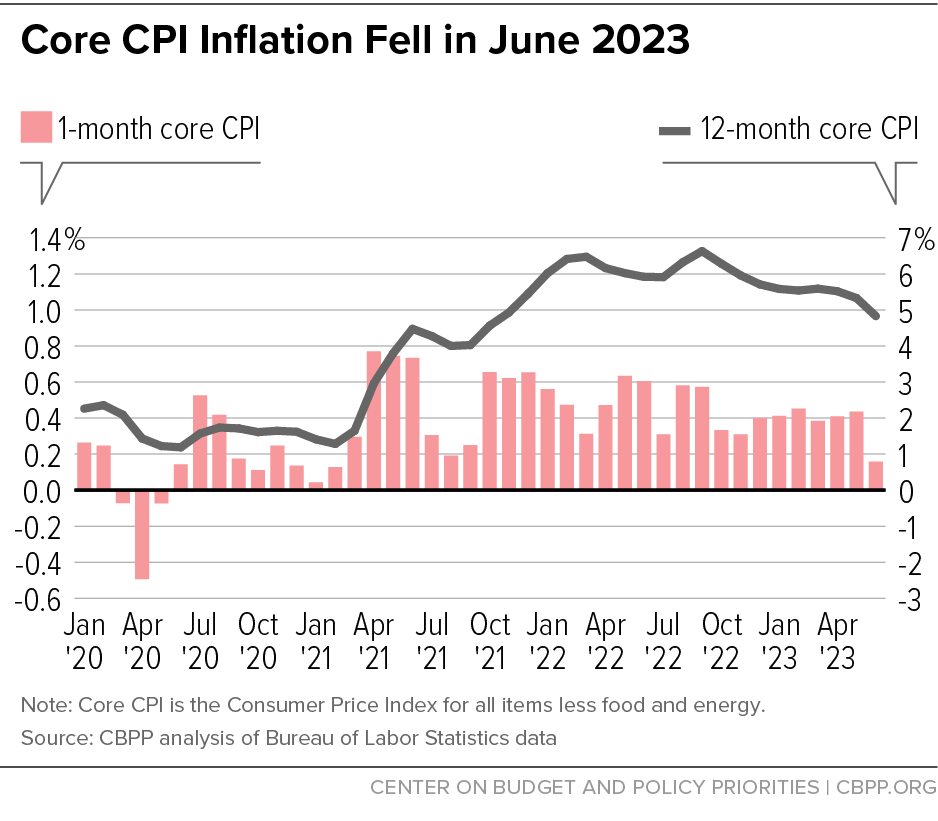

The 12-month change in the core CPI peaked at 6.6 percent in September 2022 and was down to 4.8 percent in June 2023. While the three-month change in core CPI averaged 5.1 percent at an annual rate in the first half of the year, the core CPI index rose less than 0.2 percent in June (a 1.9 percent annual rate), a rate last seen in August 2021. (See Figure 5.) A key question is whether core inflation will remain low in future months.

Twelve-month core PCE inflation has behaved similarly to 12-month core CPI inflation, fluctuating in a narrow band just below 5 percent since November 2022 before dropping to 4.1 percent in June. The annualized six-month change in June was 4.1 percent, and the annualized three-month change was 3.4 percent. In a hopeful sign, the June change was less than 0.2 percent (2.2 percent at an annual rate).

In a further effort to identify underlying inflation trends, the Fed and various analysts have looked at a variety of alternative measures, often stripping out the shelter component, which accounted for 70 percent of the June 12-month CPI increase. Shelter prices in the CPI are a combination of new and existing actual rents and owners’ equivalent rents, a majority of which are existing rents that don’t change from month to month. As a result, the CPI shelter measure lags behind market rents and doesn’t capture recent trends in shelter costs well.

Despite significant recent improvements, the Fed continues to view inflation as elevated. Fortunately, the Fed chose not to provide any specific guidance about what it will do at future meetings, which has the benefit of not tying its hands. More data will come in between now and September, and if recent trends continue, that could convince the Fed that further tightening is unnecessary. Overshooting and tightening too much could harm the strong job market and economic growth we’ve seen in 2023.

Wage Growth in a “Soft-Landing” Scenario

Tight labor markets following the worst of the pandemic led to significant wage gains, especially for jobs paying the lowest wages. Average hourly earnings for non-management jobs in June 2023 had slightly more purchasing power than in February 2020, despite inflation. Over the 12 months ending in June, real (inflation-adjusted) average hourly earnings in production and non-supervisory jobs rose 2.2 percent, with larger gains in the lowest-paying jobs. Over the same period, real average hourly earnings for all payroll jobs rose 1.2 percent.[9] The tight labor market has meant that workers in lower-paid jobs have realized the largest real wage gains.[10]

While Fed Chair Powell has stated that the initial surge in inflation “wasn’t really particularly about the labor market or wages,”[11] he has also said recently and repeatedly that an important part of reducing inflation is getting wage growth to a rate consistent with 2 percent inflation.

What Powell and others have in mind is a scenario in which nominal wage growth falls from current rates — above 4 percent — to about 3.5 percent and inflation falls somewhat faster to the Fed’s 2 percent target. With an expected 1.5 percent annual growth in labor productivity (output per hour) and 2 percent annual price increases, businesses on average could raise wages by 3.5 percent while maintaining their current profit margins. It’s possible to achieve such an outcome without going through a recession — a so-called “soft” landing — but the Fed continuing to raise rates would reduce the odds.

The economy at mid-year remains resilient in the face of substantial interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve since early 2022. But the Fed is now at a crossroads. In its determination to keep inflation from reigniting, it must remain attentive to its high-employment mandate as well, lest the employment and wage gains made by Black workers and others who are most susceptible to losses in a recession are wiped out. Further evidence prior to the Fed’s next meeting that inflation continues to fall should weigh against more tightening.