States That Still Impose Sales Taxes on Groceries Should Consider Reducing or Eliminating Them

End Notes

[1] For more discussion of issues involving sales taxation of food, see Nicholas Johnson and Iris J. Lav, “Should States Tax Food? Examining the Policy Issues and Options,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 1998, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/stfdtax98.pdf.

[2] The term “sales tax” in this paper refers to general sales taxes on goods and services as defined by the Census Bureau in its Government Finances series. (See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/gov-finances/about/glossary.html#par_textimage_1654604272https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/gov-finances/about/glossary.html#par_textimage_1654604272.) This definition includes most retail sales and use taxes but excludes nominal business license taxes as well as taxes that are levied specifically on such items as alcohol, tobacco, insurance products, motor fuels, amusements, and utilities. In several states, the sales tax is known in statute by another name.

[3] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” October 2018, https://itep.org/wp-content/uploads/whopays-ITEP-2018.pdf.

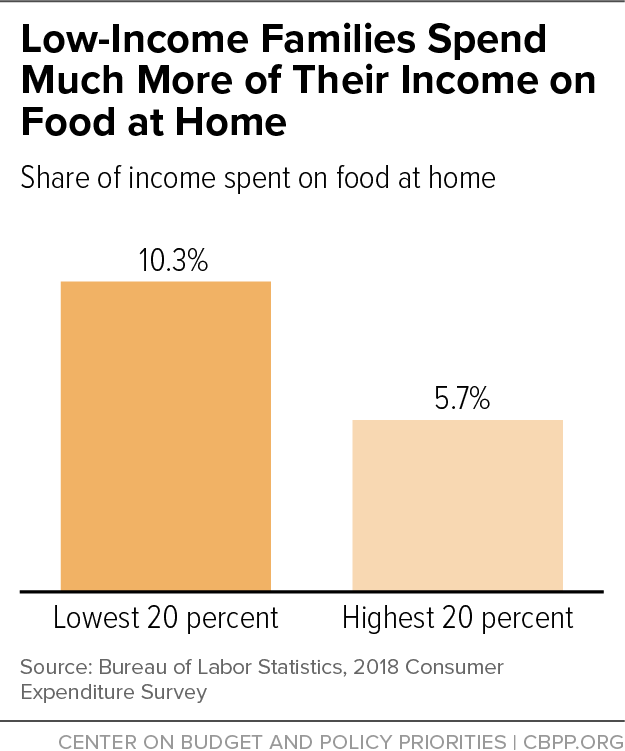

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018 Consumer Expenditure Survey (released September 10, 2019), https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables.htm#annual.

[5] Some low-income households do not qualify for SNAP due to the program’s federal income or asset limits. Also, some categories of people are not eligible for SNAP regardless of how small their income or assets may be, such as many adults without children in the home, many college students, certain legal immigrants, and immigrants without documented status. For more on who is eligible for SNAP, see Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),” updated June 25, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/policy-basics-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap.

[6] About 15 percent of households that qualify for SNAP do not enroll. U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Rates: Fiscal Year 2010 to Fiscal Year 2017,” September 2019, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/trends-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-participation-rates-fiscal-year-2010.

[7] The SNAP benefit formula assumes that 30 percent of a household’s “net” income (after a series of deductions to take into account certain other basic needs) will be used to purchase food. SNAP makes up the difference between the household’s expected contribution to food purchases and the cost of the “Thrifty Food Plan,” the Agriculture Department’s estimate of a diet intended to provide adequate nutrition at a minimal cost. See Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits,” updated November 1, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits.

[8] For more on SNAP benefit levels, see Steven Carlson, “More Adequate SNAP Benefits Would Help Millions of Participants Better Afford Food,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 30, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/more-adequate-snap-benefits-would-help-millions-of-participants-better.

[9] The eligibility criteria, amount, and refundability of the current credits vary widely. Hawaii, for instance, has a refundable credit that phases out for a single filer making over $30,000, but neither the income threshold nor the credit amount automatically adjusts to account for inflation, which shrinks the credit’s real value and reach over time. The credit also requires consumers to complete and submit a separate form with their tax return, which creates an additional barrier. The Kansas credit is nonrefundable and only applicable after all other credits have been utilized, so it provides little benefit to low-income filers, who often have little to no state income tax liability. Kansas’ credit is also only available to filers who are 55 and older, those with permanent disabilities, or those with a dependent under 18, which effectively excludes childless adults.

[10] For more on how states can update their sales taxes, see Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “Four Steps to Moving State Sales Taxes Into the 21st Century,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 9, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/four-steps-to-moving-state-sales-taxes-into-the-21st-century.

[11] Bureau of Labor Statistics data. For the 2018 figure, see https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables.htm#annual; for the 1960 figure, see https://www.bls.gov/cex/1961/Standard/ce_196061_tables.pdf.

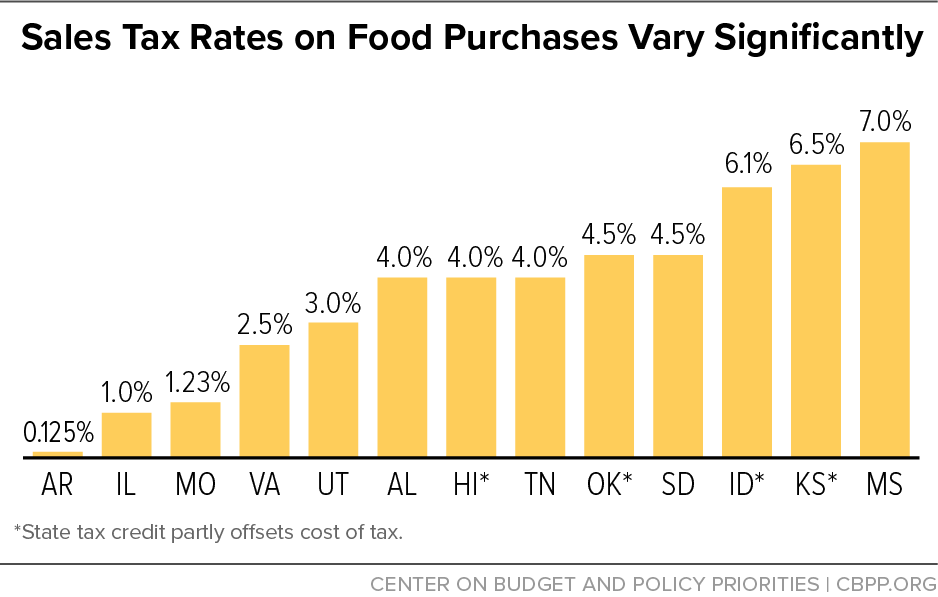

[12] Food sales tax rates (and general sales tax rates) in these states are as follows: Arkansas: 0.125 percent (6.5 percent), Illinois: 1 percent (6.25 percent), Missouri: 1.225 percent (4.225 percent), Tennessee: 4 percent (7 percent), Utah: 3 percent (6.1 percent), and Virginia: 2.5 percent (5.3 percent).

[13] South Dakota offers a limited refund of either sales or property taxes to eligible seniors and disabled residents. Most households in the state pay the full sales tax rate on food.

[14] Idaho Legislature, 2017 regular legislative session, HB 67, https://legislature.idaho.gov/sessioninfo/2017/legislation/h0067/.

[15] Utah State Legislature, 2018 general session, HB 148, https://le.utah.gov/~2018/bills/static/HB0148.html. In 2019, Alabama considered — but did not adopt — a proposal to exempt groceries from taxation and to allow cities and counties to reduce or eliminate their sales taxes on groceries. John Sharp, “Grocery tax plan halted in Alabama House committee,” AL.com, April 17, 2019, https://www.al.com/news/2019/04/grocery-tax-plan-halted-in-alabama-house-committee.html.

[16] Rebecca Moss, “Food tax bills in New Mexico Legislature met with skepticism,” Santa Fe New Mexican, February 18, 2019, https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/legislature/food-tax-bills-in-new-mexico-legislature-met-with-skepticism/article_d2e4fdd0-5cc5-5475-8146-c37314bc7fad.html. For more on attempts to restore the tax, see “Food Tax Repeal,” Think New Mexico, http://www.thinknewmexico.org/food-tax-repeal/.

[17] Utah State Legislature, 2019 second special session, SB 2001 Tax Restructuring Revisions, https://le.utah.gov/~2019S2/bills/static/SB2001.html.

[18] Bethany Rodgers and Benjamin Wood, “Utah’s Legislature, governor announce plans to repeal controversial tax reform law,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 24, 2020, https://www.sltrib.com/news/politics/2020/01/23/utahs-legislature/.