BEYOND THE NUMBERS

States Can Thoughtfully Implement Grocery Tax Reforms to Help Families and Improve Equity

States looking to advance racial and economic equity for families and people with low incomes should consider reducing or eliminating sales taxes on groceries and replacing them with fairer revenue sources, or partially offsetting them with a tax credit. States that are considering major grocery tax changes this year should do so with an eye toward their longer-term fiscal health and needs. These changes could make state tax codes more equitable, help families better afford nutritious foods and other basic needs, and maintain revenue for critical public investments.

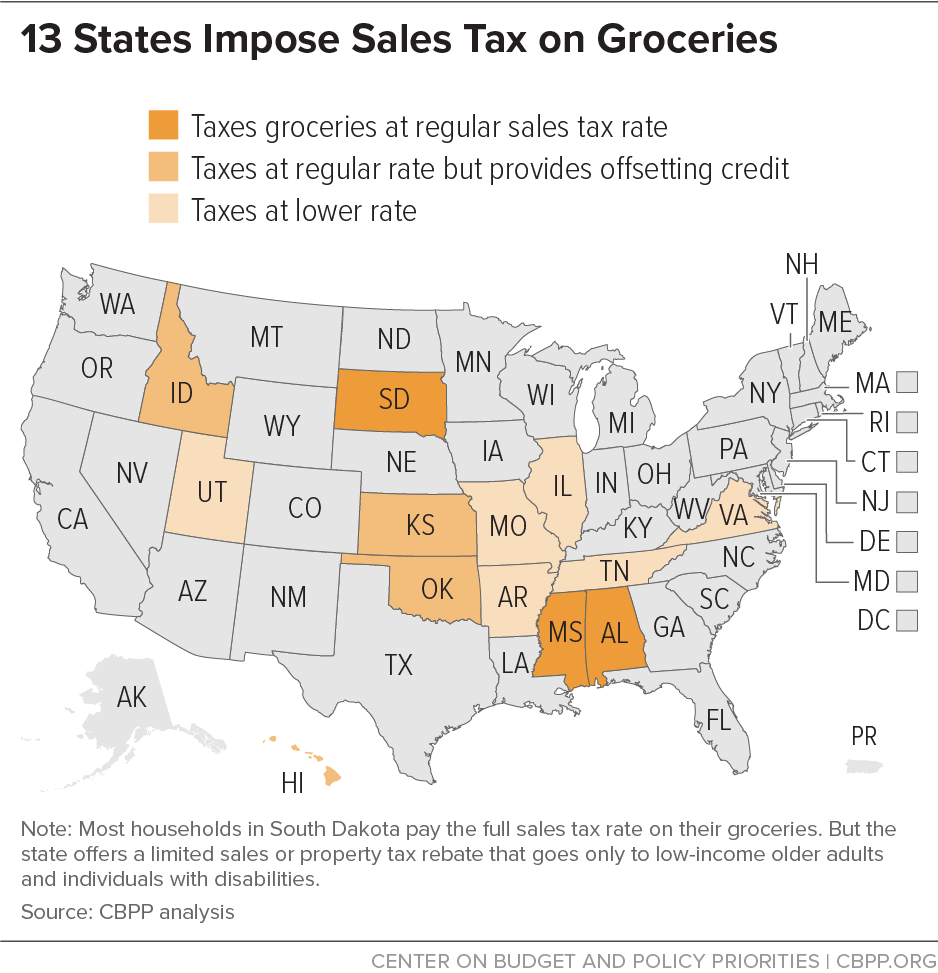

Today, only 13 states maintain grocery sales taxes. (See map.) Three of those states — Alabama, Mississippi, and South Dakota — apply the same sales tax rate to food as other goods and services. In four other states, consumers pay the full state sales tax but recoup some of those added costs by claiming a credit when they file their taxes. Six states tax groceries to a degree but levy a reduced rate. Each approach adds a noticeable cost to workers and families least able to afford it, although applying a reduced rate or offering a credit helps to mitigate some of the cost.

Reducing or eliminating grocery taxes offers states a way to help families put more food on the table and afford basic needs. Policymakers should consider major grocery tax changes but do so with care.

Sales taxes on food account for sizable amounts of revenue in several states — more than $400 million each year in Kansas, for example. States that fail to offset the drop in revenue will put funding for schools, health care, and other crucial public services at risk. This hurts all communities, but especially people of color, low- and moderate-income families, and places historically excluded from opportunity, which typically experience the most harm from public service cuts.

Meanwhile, states that choose to offset the lost revenue in a regressive way — for example, by increasing their general sales tax rate — make their tax codes more unjust, thereby hurting the same people struggling to make ends meet and whom policymakers are most trying to help.

Instead, states should replace revenue from sales taxes on groceries by:

- Adopting wealth and progressive income taxes that can raise significant revenues from those already doing very well, while also helping make state tax codes more equitable. Today, most state tax systems are upside-down, meaning they fall more sharply on households with low and moderate incomes. They also tend to exacerbate long-standing racial inequities, due in large part to an overreliance on regressive sales taxes and fees relative to revenue-raisers that collect more from taxpayers at the top. Black, Indigenous, and Latinx families, on average, are taxed at higher rates compared to white families and still experience racist and discriminatory barriers to building wealth. Seizing opportunities to raise taxes on wealthy households and profitable companies, while lowering them in targeted ways for lower-income taxpayers, is a good way to help counter a history of racist intent and impact that is baked into many state tax codes.

- Expanding and modernizing their sales tax base to keep tax rates low and revenue stable. Expanding the sales tax base to account for new and emerging technologies allows states to keep up with changes in the economy and keep their overall sales tax rate low, which especially benefits those with low incomes.

An alternative to full repeal of grocery sales taxes is for states to consider implementing or expanding existing tax credits that help families with low and moderate incomes afford the basics. Tax credits that offset grocery taxes are less expensive for states than a full repeal. An ideal credit would include adjustments for inflation, periodic payments instead of an annual lump sum, and refundability, and would reflect the true cost of the tax. States with existing credits could make similar improvements.

In 2021, at least five states (Alabama, Hawai’i, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and South Dakota) introduced legislative proposals to eliminate sales taxes on food. And at least three states (Hawai’i, Kansas, and Oklahoma) considered increasing the value of their tax credit or making it refundable. While none of these proposals became law, the elimination proposals highlight the need for equitable ways to replace the lost revenue.

In 2022, several states are already taking steps on this front. Utah’s governor has recommended a refundable grocery tax credit, targeted to low- and moderate-income families. Under this plan, a family of four with an annual income up to $60,000 would receive a $240 annual grocery tax credit. Virginia’s most recent and new governors each proposed eliminating the state grocery tax, and Illinois’ governor has proposed a one-year suspension of its grocery tax. Several proposals in Mississippi — including one that passed the House and is pending Senate review — would gradually reduce that state’s grocery tax by several percentage points. Kansas has introduced four proposals to eliminate the state’s grocery tax and the governor has made it a key part of her budget.

While such reform efforts could potentially do a great deal of good, it’s also crucial for policymakers and advocates in states navigating larger tax debates not to latch onto grocery tax improvements in isolation. For example, Mississippi leaders are weighing massive cuts to (and even elimination of) the state’s personal income tax, which could do far more harm than any reform the state’s grocery tax could reasonably offset. And in Kansas, policymakers are considering a suite of regressive tax proposals — most notably a strict tax and spending limitation — which would counteract any potential gains from cutting the state’s tax on food.

State leaders have important opportunities this year to shape a more equitable future for families of color and those with low incomes through changes to grocery sales taxes. If done carefully, these changes could reduce long-standing racial and economic inequities, make state tax codes fairer, and strengthen communities’ ability to thrive.

CBPP Research Associate Iris Hinh contributed to the research and writing of this post.