BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Alabama and Utah Join Growing Number of States Moving to Reduce or Eliminate Sales Taxes on Groceries

This year, Alabama became the latest in a growing number of states that have reduced or eliminated sales taxes on groceries — with Utah moving to do the same pending voter approval in 2024. Both are welcome developments in improving the fairness of state tax codes.

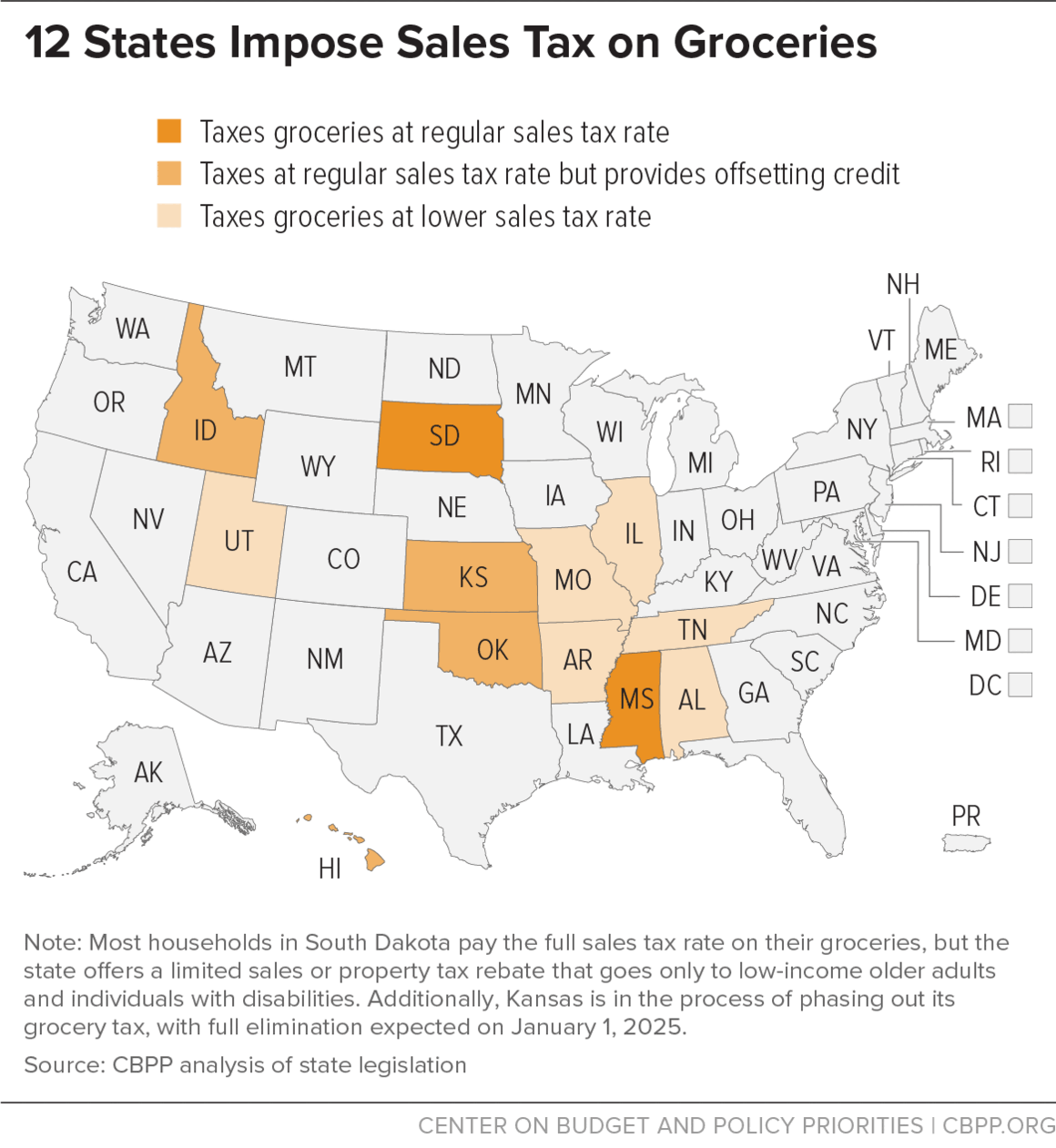

Inflation broadly and spikes in food prices specifically have spurred renewed, bipartisan attention to the impact of grocery taxes. In the past five years, Virginia and Kansas have moved to eliminate the sales tax on groceries (Kansas is phasing out its tax now), while Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee have reduced their grocery sales tax. As a result, today just 12 states apply a sales tax to food intended for home consumption (see map below).

In 2023, in addition to Alabama enacting a law to gradually reduce the grocery sales tax rate over the next two years, Utah lawmakers passed a repeal of their state tax on groceries, contingent on approval of a related constitutional amendment by voters next year. And policymakers in Idaho, Hawai’i, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Tennessee also proposed full or partial eliminations. Tennessee lawmakers eventually approved a larger package of tax cuts that included a temporary suspension of the state grocery tax; the state approved a similar temporary suspension in 2022.

Last year, as noted above, Illinois, Kansas, Tennessee, and Virginia enacted laws to eliminate or ease the cost of sales taxes on food by reducing the grocery tax rate or temporarily suspending the tax. Additionally, Idaho increased the value of its refundable grocery tax credit.

As states continue to move away from a reliance on grocery taxes to generate revenue, this is good news for tax fairness. Sales taxes contribute to regressivity in state tax codes, and overreliance on sales taxes makes state tax codes less fair overall. Everyone must eat no matter how much they earn, so sales taxes on groceries disproportionately fall on people and families with lower incomes, who must spend a larger share of that income on food to be consumed at home than those with higher incomes. According to 2021 data, those with the lowest earnings spent more than 11 percent of their incomes on groceries, while those at the top spent just 6.3 percent of their total earnings on food to be consumed at home.

While it is the right choice for tax fairness, it is true that reducing or eliminating sales taxes on groceries will also reduce the public funds available for key services such as health care and education. For example, Alabama is projected to forgo more than $150 million in 2024 and upwards of $300 million when the next phase of its reduction takes place. Economic growth and existing surpluses will help fill that hole in Alabama, but a long-term replacement is still needed.

To prevent the harmful consequences of revenue loss, in addition to reducing or eliminating sales taxes on groceries, states should consider replacing them with fairer revenue sources, such as progressive income taxes or wealth and estate taxes. That combined approach will ensure both fairness and revenue adequacy, a winning combination for families and communities.