As the income gap between the wealthiest Americans and those at the bottom and middle has widened in recent years, many states have eliminated their estate tax ― a key tool for reducing inequality and building broadly shared prosperity. States that have eliminated their estate tax should reinstate it and those with an estate tax should keep it and, if needed, improve it.

Only the very wealthiest taxpayers pay estate taxes — just 2.56 percent of estates, in the states with the tax, on average. The estate tax raises revenue for public services that build a stronger economy, protects against extreme levels of income inequality, and ensures that the wealthy cannot avoid paying taxes on certain forms of wealth.

A phase-out of the federal estate tax enacted under President Bush in June 2001 effectively repealed state estate taxes by 2005 unless states acted to retain this tax. Many states kept their estate taxes intact by passing legislation to “decouple” from the federal law or by creating separate taxes, but other states failed to act, allowing their estate taxes to disappear.

That was a mistake. Estate taxes serve many important public purposes, including:

-

Providing revenue for investments that promote a strong economy. In many states, revenues aren’t sufficient to cover the costs of critical services such as education, health care, and public infrastructure. Eighteen states plus the District of Columbia raise $4.5 billion a year from estate and inheritance taxes, which they use to support schools, roads, and other important public services. This revenue will likely fall in the coming years as some states phase in estate tax cuts that are already on the books. If all states without an estate tax reinstated this tax, they could raise an additional $3 billion to $6 billion a year. In addition, the erosion of the tax in the District of Columbia and states like Maryland and New York could be halted by eliminating future increases in the exemption levels that reduce the number of wealthy estates who pay the tax.

An estate tax will help — not harm — a state’s economy. Estate tax revenue supports services that make a state an attractive place to do business and live. Research confirms that very few wealthy individuals move as a result of an estate tax.

- Reducing inequality. The vast majority of taxpayers would never owe estate taxes. These taxes are paid by a small share of the very wealthy families — those most able to afford them. Despite opponents’ claims, small, family-owned farms and businesses owe estate tax in very few instances. And by increasing the share of their income that the wealthiest must pay, estate taxes can make state tax systems — which now require the lowest-income families to pay the most — more equitable.

- Closing a loophole that benefits the wealthiest. Without an estate tax, many unrealized capital gains go untaxed at the state level. This happens when an asset that has increased in value is not sold during the owner’s lifetime, leaving the heirs to gain the profit.

History of Federal and State Estate Taxes

Federal and state taxes on inherited wealth have long been used to fund public services. The first federal tax was a stamp tax required for wills established by Congress in 1797. Between then and 1916 — mainly in wartime — the federal government used other temporary taxes on inherited wealth. Over this same time, an increasing number of states levied their own estate taxes.

In the early 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt and others advocated for a permanent federal estate tax as a means to reduce wealth inequality, which had grown dramatically — as it has again, today. The federal government established the modern, permanent estate tax in 1916.[1] Then, as now, only a very small percentage of the wealthiest estates owed estate taxes.[2]

The establishment of a permanent federal tax threatened to limit state revenue-raising capacity as some 43 states levied estate taxes in 1916. To eliminate state-federal tension and simplify taxation of inherited wealth, the federal government in 1924 added a credit to estates for state estate or inheritance taxes paid. Under the system, estates received a dollar-for-dollar credit that reduced their federal estate tax liability by the amount they paid to the state.[3]

Prior to the passage of a federal estate tax cut in 2001, every state levied an estate tax that allowed them to “pick up” a share of federal estate tax revenues. The state “pick-up” taxes didn’t increase total estate tax liability for estates, due to the federal credit. In addition, about a dozen states levied a separate inheritance or estate tax not linked to the federal estate tax. Some portion of these taxes typically counted as a credit against federal estate taxes.

As part of the 2001 federal legislation, the federal estate tax credit to which most state estate taxes were tied was repealed. The repeal of the credit for state estate and inheritance taxes was phased in over four years, with repeal fully effective in 2005. (The American Taxpayer Relief Act, enacted in 2013, made that repeal permanent.) The repeal of the credit resulted in the automatic loss of states’ pick-up taxes, which states had set to equal the amount of the federal credit.

Despite this, a number of states retained the revenue that these taxes generated by “decoupling” from the federal tax code. (Decoupling means protecting the relevant parts of their state tax code from the changes in the federal tax code, in most cases by remaining linked to federal law as it existed prior to the change.) In addition, the federal legislation didn’t affect states that levy stand-alone inheritance or estate taxes not tied to the federal tax code.

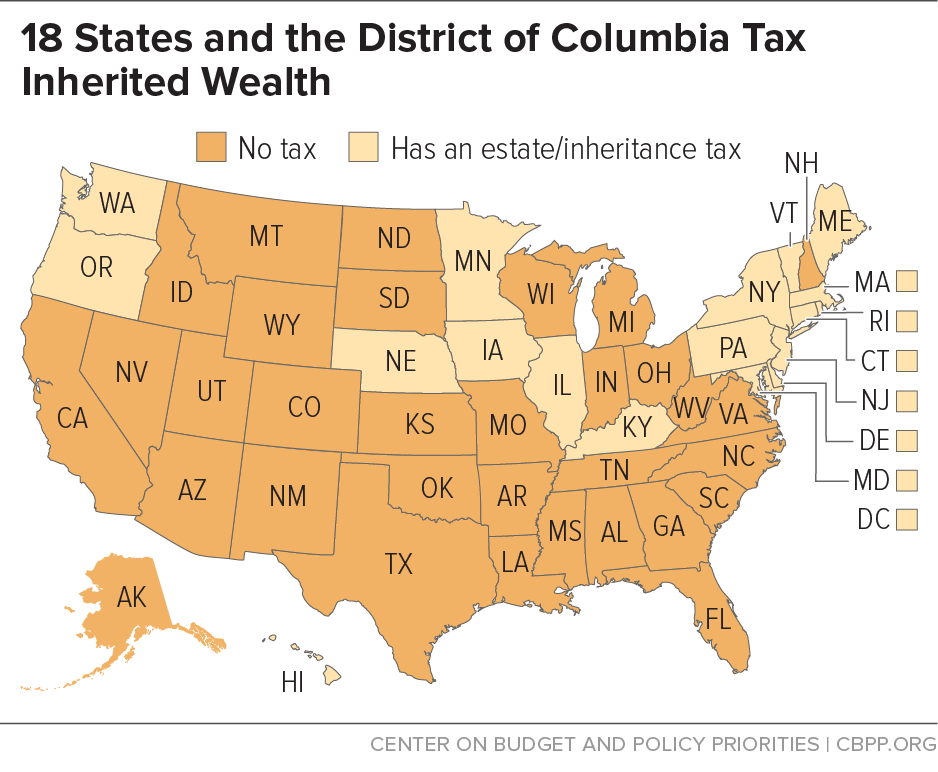

Today, 18 states and the District of Columbia continue to collect either an estate or inheritance tax. (See Figure 1.) In total, these states are collecting over $4.5 billion per year from these taxes. Of those 18 states, 14 levied pick-up taxes prior to 2001 and retained estate taxes. And of these, nine states — Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont — and the District of Columbia decoupled from the federal estate tax law and continue to levy an estate tax that is the same or very similar to the earlier pick-up tax. Five states — Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Oregon, and Washington — replaced their pick-up taxes with estate taxes that are not tied to the federal tax.

The remaining four states — Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania — levy an inheritance tax (rather than an estate tax) that was never tied to the federal pick-up tax.[4] In addition, two states — Maryland and New Jersey — levy both an estate tax that is similar to the pre-2001 pick-up tax and a separate inheritance tax.

As the nation’s economy has slowly recovered from the Great Recession, overall state revenues have exceeded their pre-recession levels, better enabling states on average to fund services. But in many states, revenues still aren’t sufficient to cover the costs of needed services such as education, health care, and improving roads, water systems, and other public infrastructure. For example, state cuts in funding for colleges and universities have led to sharp tuition increases, likely pushing college out of reach for more students.[5] With revenue collections remaining below historic averages as a share of the economy in many states, it makes sense for them to consider tax increases to support services crucial to long-term economic growth.

Existing state estate and inheritance taxes generate over $4.5 billion annually. (See Table 2.) If states without an estate tax reinstated one, they could raise an additional $3 billion to $6 billion each year. (Table 3 shows estimates of the magnitude of potential state estate tax revenue calculated using federal data. Estimates prepared by states using local data would be more precise.)

Some critics claim that an estate tax harms a state’s economy by causing retirees and elderly people to leave the state or by discouraging them from moving there, but there’s no credible evidence to support this claim. Recent analyses of the effect of taxes on interstate moves show that differences in tax levels among states have little to no effect on whether and where people move.[6]

At most, recent studies find that estate taxes have a small effect on the residence decisions of the very wealthy elderly; few people are likely to be affected, and the size of the effect is small. On the whole, after their working years, residents move from a state to retire in warmer areas or in locales with lower housing costs.[7]

Two researchers, in particular, have examined the effect of estate taxes on interstate moves. The research of University of New Hampshire economist Karen Smith Conway — the leading academic expert on this issue[8] — finds some evidence that the absence of estate and income taxes may have a weak effect on the states to which elderly people choose to move, but the presence of these taxes does not drive elderly people out of the states levying them. Even these relationships, however, are often not statistically significant or uniform across various possible measures of tax levels. In summarizing her findings, Conway says, “Put simply, state tax policies toward the elderly have changed substantially while elderly migration patterns have not. . . . Our results, as well as the consistently low rate of elderly interstate migration, should give pause to those who justify offering state tax breaks to the elderly as an effective way to attract and retain the elderly.”[9]

“Our results are overwhelming in their failure to reveal any consistent effect of state tax policies on elderly migration across state lines.”

Karen Smith Conway

University of New Hampshire economist

She concludes, “Our results are overwhelming in their failure to reveal any consistent effect of state tax policies on elderly migration across state lines.”[10]

A 2004 study by Jon Bakija of Williams College and Joel Slemrod of the University of Michigan Business School focused on the impact of taxes on the wealthiest elderly — those who file federal estate tax returns. Although estate tax opponents often cite this study because it found that high state estate and inheritance taxes reduce the number of federal estate tax returns filed in the state, the effect they found is very small. They concluded that any resulting revenue losses “would not be large relative to the revenue raised by the tax.”[11]

This suggests that the negative impact, if any, of an estate tax on a state’s economy and revenue collections is likely to be small. The loss of revenue from reducing or eliminating the estate tax, on the other hand, reduces state resources that can be used for public investments that undergird economic growth. Cuts in state services resulting from eliminating an estate tax can discourage businesses and individuals — both retirees and others — from remaining in or relocating to a state, likely doing more harm to a state’s future economic growth than any small benefit that might come from having no estate tax.

Since the 1970s, wealth has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a relatively small share of families in the United States. The wealthiest 3 percent of all households control over half of national wealth; the bottom 90 percent hold only one-quarter.[12]

The estate tax is the only state tax that is paid almost entirely by the wealthy. That makes it a valuable part of state tax systems which, overall, require the highest-income families to pay a smaller share of their income than others. In general, the higher a household’s income, the lower the percentage of that income it pays in state taxes. That is, most state tax systems are “regressive.” This situation results largely from states’ substantial reliance on consumption taxes like the sales tax and cigarette taxes. Since the estate tax is paid only by the wealthiest, enacting or retaining one makes a state’s tax structure more equitable.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Connecticut |

$2 million |

| Delaware |

$5.45 million |

| District of Columbia |

$1 million* |

| Hawaii |

$5.45 million |

| Illinois |

$4 million |

| Maine |

$5.45 million |

| Maryland |

$2 million* |

| Massachusetts |

$1 million |

| Minnesota |

$1.6 million |

| New Jersey |

$675,000 |

| New York |

$3.125 million* |

| Oregon |

$1 million |

| Rhode Island |

$1.5 million |

| Vermont |

$2.75 million |

| Washington |

$2.079 million |

The size of estates that are subject to a state estate tax varies considerably. Only estates that are larger than the exemption level that a state sets owe estate tax. Exemptions range from the federal exemption that was in effect in the early 2000s ($675,000) to the current federal exemption ($5.45 million). Most state exemptions are between $1 million and $2 million. (See Table 1.)

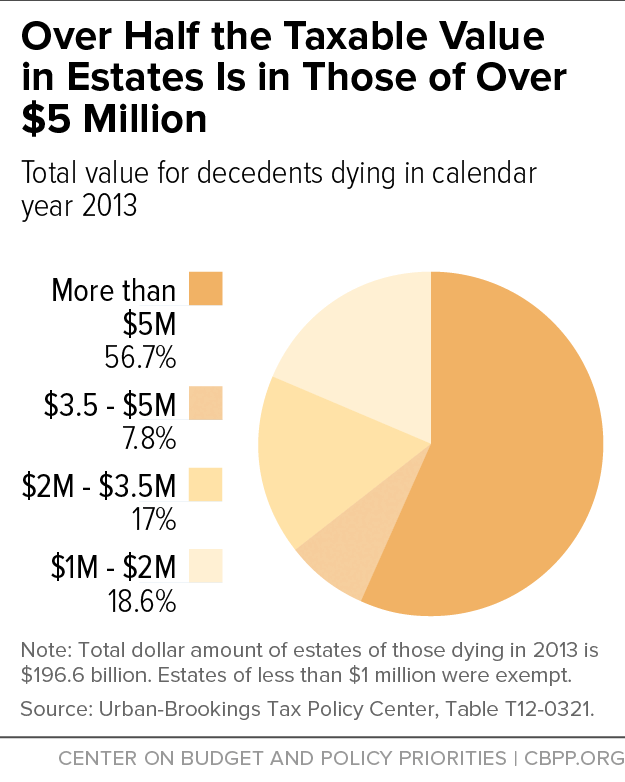

The exemption size affects the number of estates that pay the tax and the amount of revenue the state collects. For example, in 2013, if the federal estate tax exemption had been $1 million, estates between $1 million and $2 million would have made up just over half of taxable estates but only one-fifth of the total value of taxable estates, according to Tax Policy Center estimates. Estates of more than $5 million, at the other end of the income scale, would have made up only 13 percent of estates owing tax but 57 percent of taxable value. (See Figure 2.) The distribution varies by state but is similar to the national averages.

Some states have raised their exemptions in recent years, believing it easier to administer a state estate tax that applies only to estates that owe federal tax. States that use the current federal exemption level ($5.45 million) collect one-third to one-half less revenue than they would if all estates of $1 million or more — the federal exemption in 2001 when Congress eliminated the state credit — paid the tax.

The optimal exemption level for a state depends on many factors such as the distribution of wealth in the state, other elements of the state’s tax system, and desire for administrative ease balanced with the state’s need for revenue to support services.

When a state needs revenue to benefit the public good, failing to adequately tax the state’s wealthiest individuals — those most able to afford to pay — does not make sense. An estate tax also improves states’ ability to finance services in the future. One long-recognized flaw of state revenue systems is that because of their heavy reliance on consumption taxes such as the sales tax, they tend to erode relative to the economy over time. For example, state sales taxes have not kept pace with trends such as the growth of the service sector and of e-commerce.[13] State estate taxes offset some of the erosion by taxing the incomes of the highest-income households, which have risen more quickly than others — a trend that shows no sign of abating.

Arguably, the small minority of families that pay the estate tax are those who least need a tax break. The federal estate tax, owed only by estates worth $5.45 million or more, is paid not even by the top 1 percent of households, but by just two-tenths of 1 percent, or 2 out of every 1,000 households.[14] The share of estates that would owe a state estate tax that used the federal exemption varies by state depending on the distribution of wealth in the state but is less than 0.3 percent in every state.[15] (See box, “Exemption Levels Vary by State,” above, and Table 4, which shows the number and percent of estates that owe federal tax for each state.) Only 2.56 percent of estates owe tax in the states that currently levy a state estates tax, on average.

States could also choose to levy an estate tax on all estates valued at more than $1 million — the federal law in effect at the time the state estate tax credit was eliminated. An estate tax at this level would raise about twice as much revenue. When the federal exemption was $1 million, still just 1.3 percent of estates owed estate tax.[16]

Critics of the estate tax inaccurately claim that it is a problem for small, family-owned farms and small businesses. They contend that farms and small business must often be sold to pay estate taxes. The reality is far different. Very few family farms or small businesses owe estate tax, and those that do almost always have sufficient liquid assets (such as bank accounts, stocks, bonds, and insurance) to pay the tax. Only roughly 20 small business and small farm estates in the entire country owed any federal estate tax in 2013, according to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.[17]

Only roughly 20 small business and small farm estates in the entire country owed any federal estate tax in 2013.

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center

More small businesses and farms would likely have to pay an estate tax in states with exemptions lower than the federal exemption, but the number would still be very small. A 2005 Congressional Budget Office study found that with an exemption of $1.5 million, only 27 small farms and 82 small businesses in the country would have owed estate tax and would not have had sufficient liquid resources to pay the tax.[18]

The wealthiest people often accumulate large estates without ever paying income taxes on the gains in those estates’ value by keeping their wealth in unrealized capital gains. The estate tax can ensure that this income from wealth is taxed in a manner comparable to the taxes that other families pay on wages and other forms of income.

Under the current tax system, capital gains tax is due on the appreciation of assets, such as real estate, stock, or an art collection, only when the owner “realizes” the gain (usually by selling the asset). Therefore, the increase in the value of an asset is never subject to income tax if the owner holds on to the asset until death.

These unrealized capital gains account for a significant proportion of the assets held by the large estates that make up the bulk of estate tax payers. Unrealized capital gains make up from 25 to 32 percent of the value of estates worth between $3.5 million and $10 million — and as much as 55 percent of the value of estates worth more than $100 million.[19] (See Figure 3.)

If the states that lack an estate tax do not reinstate one, a very small number of wealthy families will be able to continue passing along large concentrations of wealth from generation to generation, free from state taxation.

State estate taxes continue to be the subject of much discussion and legislation. A number of states have made changes in the wake of the 2001 federal legislation that left many states without an estate tax as of 2005. For example, Delaware and Hawaii reinstated their estate taxes in 2010. Some states that initially retained the tax subsequently eliminated it, such as North Carolina, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. Other states that kept the tax have raised exemption levels.[20]

There are perennial calls to eliminate existing state estate taxes. For example, Maine’s legislature defeated Governor Paul LePage’s proposed elimination of the state’s estate tax earlier this year.[21] And there have been calls by elected officials and others to reduce or eliminate Connecticut’s and New Jersey’s estate tax.[22]

To reduce inequality and raise revenue for investments that promote a strong economy, states should resist those calls and instead consider improvements such as changes to exemption levels and rates that address specific concerns, if needed. In addition, states without an estate tax should consider reinstating it, as part of a broader effort to build an economy whose benefits are widely shared.[23]

| TABLE 2 |

|---|

Current State Estate and Inheritance Taxes Raise More than $4.5 Billion

(amounts in thousands) |

|---|

| |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

|---|

| Connecticut |

439,519 |

169,636 |

176,763 |

| Delaware |

5,300 |

1,300 |

5,800 |

| Hawaii |

14,886 |

14,789 |

12,071 |

| Illinois |

309,000 |

294,000 |

355,000 |

| Iowa |

86,810 |

91,030 |

86,980 |

| Kentucky |

41,326 |

45,844 |

50,976 |

| Maine* |

79,083 |

23,962 |

38,407 |

| Maryland |

234,615 |

213,785 |

243,418 |

| Massachusetts* |

313,394 |

401,512 |

304,300 |

| Minnesota |

158,938 |

177,432 |

145,292 |

| Nebraska** |

55,035 |

NA |

66,731 |

| New Jersey |

623,840 |

687,436 |

793,508 |

| New York |

1,014,000 |

1,238,000 |

1,109,000 |

| Oregon** |

101,831 |

85,491 |

110,994 |

| Pennsylvania |

845,258 |

877,423 |

1,002,259 |

| Rhode Island |

28,489 |

43,592 |

34,202 |

| Vermont* |

15,400 |

35,500 |

9,900 |

| Washington |

104,449 |

156,019 |

154,040 |

| District of Columbia |

39,700 |

32,100 |

48,274 |

| Total |

4,509,873 |

4,588,851 |

4,747,915 |

| TABLE 3 |

|---|

| State |

$1 million exemption |

$3.5 million exemption |

$5.45 million exemption |

|---|

| Alabama |

$110 |

$60 |

$60 |

| Alaska |

$10 |

$0 |

$0 |

| Arizona |

$130 |

$80 |

$70 |

| Arkansas |

$70 |

$40 |

$40 |

| California |

$1,740 |

$1,030 |

$950 |

| Colorado |

$110 |

$70 |

$60 |

| Connecticut |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Delaware |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Florida |

$1,050 |

$620 |

$580 |

| Georgia |

$190 |

$120 |

$110 |

| Hawaii |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Idaho |

$20 |

$10 |

$10 |

| Illinois |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Indiana |

$140 |

$80 |

$70 |

| Iowa* |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Kansas |

$60 |

$30 |

$30 |

| Kentucky* |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Louisiana |

$60 |

$30 |

$30 |

| Maine |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Maryland |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Massachusetts |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Michigan |

$240 |

$140 |

$130 |

| Minnesota |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Mississippi |

$40 |

$30 |

$20 |

| Missouri |

$180 |

$110 |

$100 |

| Montana |

$20 |

$10 |

$10 |

| Nebraska |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Nevada |

$70 |

$40 |

$40 |

| New Hampshire |

$50 |

$30 |

$30 |

| New Jersey |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| New Mexico |

$40 |

$30 |

$20 |

| New York |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| North Carolina |

$170 |

$100 |

$100 |

| North Dakota |

$10 |

$10 |

$0 |

| Ohio |

$320 |

$190 |

$180 |

| Oklahoma |

$90 |

$50 |

$50 |

| Oregon |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Pennsylvania* |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Rhode Island |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| South Carolina |

$90 |

$60 |

$50 |

| South Dakota |

$10 |

$10 |

$10 |

| Tennessee |

$130 |

$80 |

$70 |

| Texas |

$490 |

$290 |

$270 |

| Utah |

$40 |

$20 |

$20 |

| Vermont |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Virginia |

$240 |

$140 |

$130 |

| Washington |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| West Virginia |

$20 |

$10 |

$10 |

| Wisconsin |

$120 |

$70 |

$60 |

| Wyoming |

$20 |

$10 |

$10 |

| District of Columbia |

Has tax |

Has tax |

Has tax |

| Total Potential |

$6,070 |

$3,610 |

$3,330 |

| TABLE 4 |

|---|

| State of residence |

Estate tax returns |

Number of deaths (CDC) 2013 |

|

|---|

| |

Number |

|

Percent |

|---|

| Total |

5,158 |

2,606,993 |

0.20% |

| Alabama |

52 |

50,189 |

0.10% |

| Alaska |

* 5 |

3,997 |

0.13% |

| Arizona |

76 |

50,534 |

0.15% |

| Arkansas |

23 |

30,437 |

0.08% |

| California |

1,053 |

248,359 |

0.42% |

| Colorado |

50 |

33,712 |

0.15% |

| Connecticut |

111 |

29,632 |

0.37% |

| Delaware |

* 4 |

7,967 |

0.05% |

| District of Columbia |

* 26 |

4,719 |

0.55% |

| Florida |

634 |

181,112 |

0.35% |

| Georgia |

87 |

75,088 |

0.12% |

| Hawaii |

* 8 |

10,505 |

0.08% |

| Idaho |

* 18 |

12,434 |

0.14% |

| Illinois |

249 |

103,401 |

0.24% |

| Indiana |

80 |

60,716 |

0.13% |

| Iowa |

51 |

28,948 |

0.18% |

| Kansas |

44 |

25,414 |

0.17% |

| Kentucky |

27 |

43,759 |

0.06% |

| Louisiana |

60 |

43,270 |

0.14% |

| Maine |

21 |

13,547 |

0.16% |

| Maryland |

72 |

45,689 |

0.16% |

| Massachusetts |

112 |

54,567 |

0.21% |

| Michigan |

100 |

92,408 |

0.11% |

| Minnesota |

84 |

40,987 |

0.20% |

| Mississippi |

* 14 |

30,703 |

0.05% |

| Missouri |

69 |

57,444 |

0.12% |

| Montana |

* 12 |

9,511 |

0.13% |

| Nebraska |

32 |

15,754 |

0.20% |

| Nevada |

60 |

21,468 |

0.28% |

| New Hampshire |

25 |

10,897 |

0.23% |

| New Jersey |

145 |

71,403 |

0.20% |

| New Mexico |

14 |

16,805 |

0.08% |

| New York |

457 |

150,919 |

0.30% |

| North Carolina |

112 |

93,329 |

0.12% |

| North Dakota |

* 15 |

6,233 |

0.24% |

| Ohio |

126 |

113,258 |

0.11% |

| Oklahoma |

43 |

38,384 |

0.11% |

| Oregon |

50 |

33,939 |

0.15% |

| Pennsylvania |

147 |

129,123 |

0.11% |

| Rhode Island |

22 |

9,792 |

0.22% |

| South Carolina |

43 |

44,582 |

0.10% |

| South Dakota |

* 21 |

7,099 |

0.30% |

| Tennessee |

35 |

63,406 |

0.06% |

| Texas |

325 |

179,183 |

0.18% |

| Utah |

19 |

16,366 |

0.12% |

| Vermont |

* 7 |

5,639 |

0.12% |

| Virginia |

140 |

62,716 |

0.22% |

| Washington |

69 |

51,264 |

0.13% |

| West Virginia |

* 17 |

21,843 |

0.08% |

| Wisconsin |

57 |

50,026 |

0.11% |

| Wyoming |

* 7 |

4,516 |

0.16% |