What the 2023 Trustees’ Report Shows About Social Security

End Notes

[1] Social Security Administration (SSA), “The 2023 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds,” April 2023, https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2023/.

[2] SSA, “The 2022 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds,” June 2022, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/TR/2022/.

[3] SSA, “Summary: Actuarial Status of the Social Security Trust Funds,” March 2023, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/trust-funds-summary.html.

[4]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table IV.B4.

[5]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table VI.G4.

[6]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table II.D1.

[7]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table IV.B1.

[8] Elisa A. Walker, Virginia P. Reno, and Thomas N. Bethell, “Americans Make Hard Choices on Social Security: A Survey with Trade-Off Analysis,” National Academy of Social Insurance, October 23, 2014, https://www.nasi.org/research/disability/report-americans-make-hard-choices-on-social-security-a-survey-with-trade-off-analysis/; Pew Research Center, “Political Polarization in the American Public,” June 12, 2014, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/.

[9] Kathleen Romig, “Increasing Payroll Taxes Would Strengthen Social Security,” CBPP, September 27, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/increasing-payroll-taxes-would-strengthen-social-security.

[10] 2023 Trustees’ Report, Table IV.B1; Social Security payroll taxes equal 12.4 percent of taxable payroll, while dedicated income taxes that higher-income beneficiaries pay on a portion of their Social Security benefits contribute a gradually rising percentage of taxable payroll.

[11] SSA, “Contribution And Benefit Base,” https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/cbb.html.

[12]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table IV.B1.

[13]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table II.D2.

[14]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table VI.G4.

[15] SSA, “Monthly Statistical Snapshot, February 2023,” March 2023, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/quickfacts/stat_snapshot/.

[16]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table V.A3.

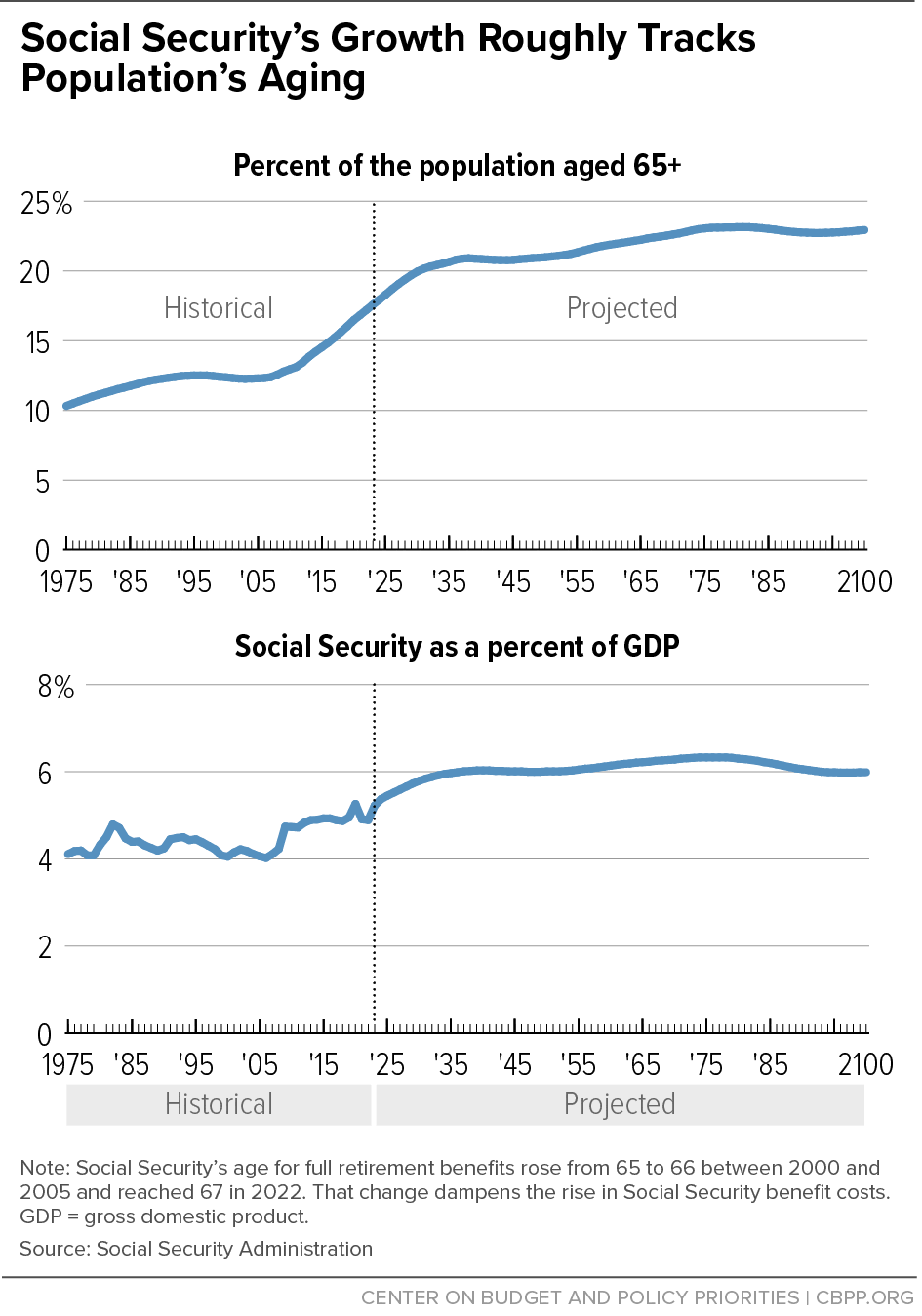

[17] The rise in the full retirement age from 66 to 67, which phased in between 2017 and 2022, slowed the growth of program costs, as the previous rise from 65 to 66 did. For an explanation, see Kathleen Romig, “Raising Social Security’s Retirement Age Cuts Benefits for All Retirees,” CBPP, January 20, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/raising-social-securitys-retirement-age-cuts-benefits-for-all-retirees.

[18]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table IV.B4.

[19] Barry F. Huston, “Social Security: What Would Happen If the Trust Funds Ran Out?” Congressional Research Service, updated September 28, 2022, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33514.pdf.

[20] In addition, the 2015 bipartisan budget agreement addressed DI solvency by temporarily reallocating payroll taxes between the DI and OASI trust funds, which extended the solvency of the DI trust fund by several years but did not affect the projected exhaustion year of the OASI fund.

[21] CBPP, “Policy Basics: Social Security Disability Insurance,” updated March 13, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/social-security-disability-insurance.

[22]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table V.C5.

[23]2023 Trustees’ Report , Table VI.E1.

[24] Congressional Budget Office, “CBO’s 2022 Long-Term Projections for Social Security,” December 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58564.

[25] CBPP, “Policy Basics: Understanding the Social Security Trust Funds,” updated April 17, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/understanding-the-social-security-trust-funds.

[26] Paul N. Van de Water and Kathleen Romig, “Social Security Benefits Are Modest,” CBPP, updated January 8, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/social-security-benefits-are-modest.

[27] CBPP, “Policy Basics: Top Ten Facts About Social Security,” updated April 17, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/policy-basics-top-ten-facts-about-social-security.

[28] SSA, “Annual Statistical Supplement, 2022,” Table 4.B1, December 2022, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2022/4b.html#table4.b1.

[29] Romig, “Increasing Payroll Taxes Would Strengthen Social Security.”

[30]2023 Trustees’ Report, Table VI.G6.

[31] Walker, Reno, and Bethell, op. cit.; Pew Research Center, op. cit.