Despite the economic upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the long-term outlook for the Social Security trust funds has deteriorated only modestly, the latest annual report from the program’s trustees shows.[1] Social Security can pay full benefits for 13 more years, but then faces a significant, though manageable, funding shortfall.[2] Several key points emerge from the report.

- The trustees estimate that, if policymakers take no further action, Social Security’s combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund reserves will be depleted in 2034. This is one year earlier than projected in last year’s report, which did not take into account the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting recession.

- While most of Social Security’s benefits are funded by the payroll taxes collected from today’s workers, the program has also accumulated $2.9 trillion in trust fund reserves over the past three decades. During that period, Social Security’s income exceeded its costs, and the program invested the surplus in interest-bearing Treasury securities. Over the next 13 years, those reserves will make up the difference between Social Security’s income and costs.

- After 2034, Social Security could still pay about three-quarters of scheduled benefits using its tax income even if policymakers took no steps to shore up the program. Those who claim that Social Security won’t be around at all when today’s young adults retire and that young workers will receive no benefits either misunderstand or misrepresent the trustees’ projections.

- The program’s shortfall amounts to 1.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) over the next 75 years (and about 1.4 percent of GDP in the 75th year).

The program’s trustees have again revised their estimate for the DI trust fund, projecting that its reserves will last through 2057 — eight years sooner than the 2020 report. Because DI costs and income are in close balance, even small changes can significantly alter the DI trust fund’s projected reserve depletion date.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, its economic repercussions, and the legislative response will continue to affect Social Security’s financial outlook, causing uncertainty in the near term. This year’s report, the first to incorporate the effects of the pandemic, shows that so far Social Security’s long-term outlook remains similar to what the trustees expected before the pandemic. (See Table 1.)

Policymakers should address Social Security’s long-term shortfall primarily by increasing Social Security’s tax revenues. Social Security will necessarily require an increasing share of our nation’s resources as the population ages, and polls show a widespread willingness to pay more to strengthen the program. Recent trends also justify boosting Social Security’s payroll tax revenue: Social Security’s tax base has eroded since the last time policymakers addressed solvency in 1983, largely due to increased earnings inequality and the rising cost of non-taxed fringe benefits, such as health insurance.

For Social Security as a whole, the outlook in the 2021 trustees’ report remains similar to last year’s. The report focuses on the next 75 years — a horizon that spans the lifetime of just about everybody now old enough to work. With no tax increases scheduled, the trustees project that the program’s tax income will remain around 13 percent of taxable payroll.[3] (Taxable payroll — the wages and self-employment income up to Social Security’s taxable maximum, currently $142,800 a year — represents slightly over one-third of GDP.) Meanwhile, program costs are expected to climb, largely due to the aging of the population. Costs will grow more steeply for about 20 years and then moderate, rising to roughly 18 percent of taxable payroll in 75 years. Interest earnings, long an important component of the trust funds’ income, will shrink and eventually disappear.

Over the entire 75-year period, the trustees put the Social Security shortfall at 3.54 percent of taxable payroll; the shortfall is concentrated in the later decades of the projection. Expressed as a share of the nation’s economy, the 75-year shortfall equals 1.2 percent of GDP.

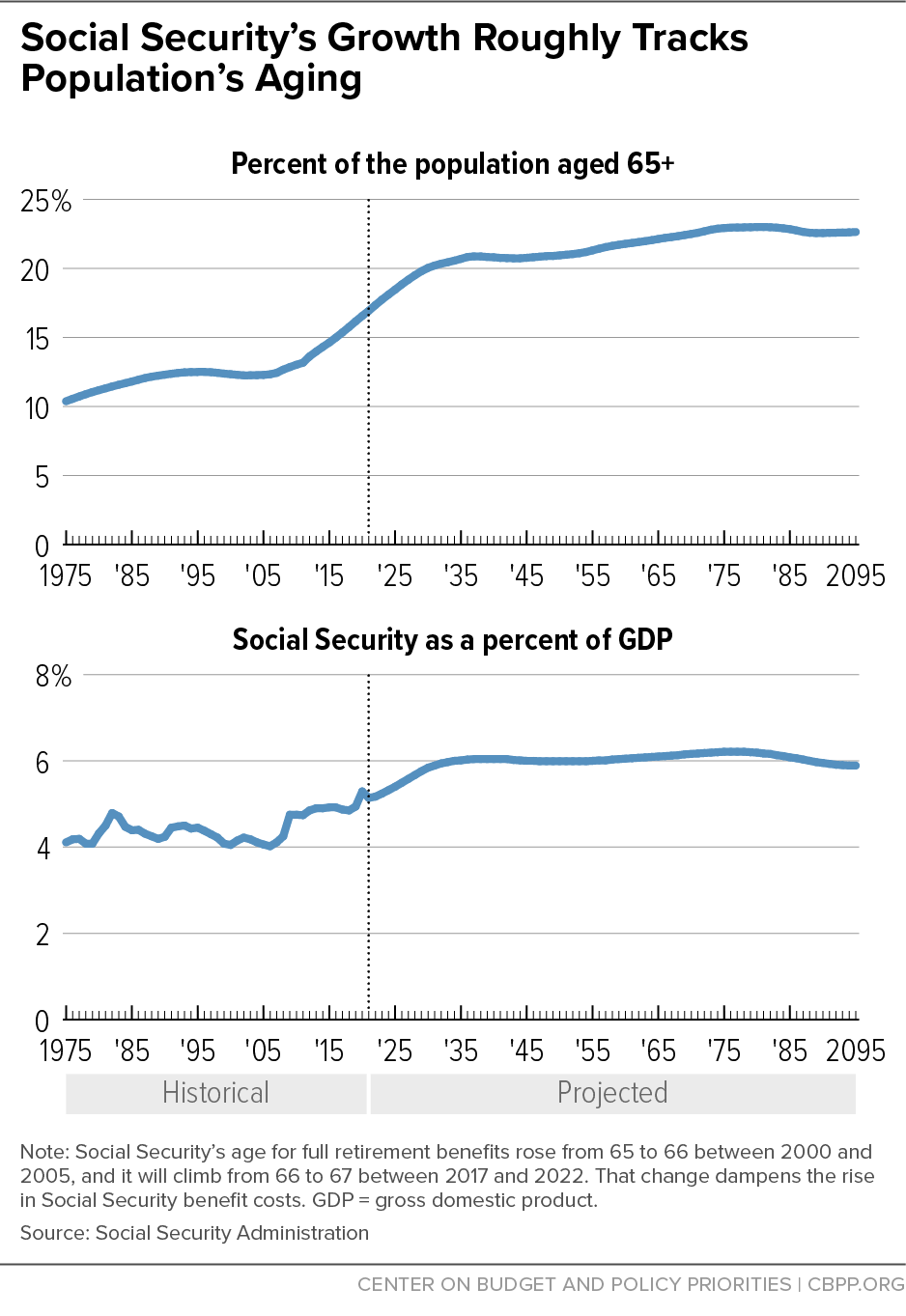

While Social Security provides earned benefits to people of all ages — young children and their surviving parents who have lost a family breadwinner, working-age adults who have suffered a serious disability, and retired workers and elderly widows and widowers — about 4 in 5 beneficiaries are older Americans. The elderly share of the population will climb steeply over the next 15 years, from just under 1 in 6 Americans to 1 in 5, and then inch up thereafter. Social Security costs as a percentage of GDP will rise slightly less than that due to already enacted increases in the age for full retirement benefits (previously 65, then 66, and now nearly 67, a level it will reach in 2022), which dampen the rise in benefit costs.[4] (See Figure 1.) These facts reinforce the point that Social Security’s fundamental challenge is demographic, traceable to a rising number of beneficiaries rather than to escalating costs per beneficiary.

| TABLE 1 |

| |

Change in actuarial balance (as percentage of taxable payroll over 75 years) since previous report due to… |

|

| Year of report |

Legislation and regulations |

Change in valuation period |

All other* |

Total change |

Actuarial balance |

Year of exhaustion |

| 1999 |

0.00 |

-0.08 |

0.20 |

0.12 |

-2.07 |

2034 |

| 2000 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.24 |

0.17 |

-1.89 |

2037 |

| 2001 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.10 |

0.03 |

-1.86 |

2038 |

| 2002 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.06 |

-0.01 |

-1.87 |

2041 |

| 2003 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

-1.92 |

2042 |

| 2004 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.10 |

0.03 |

-1.89 |

2042 |

| 2005 |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

-1.92 |

2041 |

| 2006 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

-0.03 |

-0.09 |

-2.02 |

2040 |

| 2007 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

0.13 |

0.06 |

-1.95 |

2041 |

| 2008 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

0.32 |

0.26 |

-1.70 |

2041 |

| 2009 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.25 |

-0.30 |

-2.00 |

2037 |

| 2010 |

0.14 |

-0.06 |

0.00 |

0.08 |

-1.92 |

2037 |

| 2011 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.25 |

-0.30 |

-2.22 |

2036 |

| 2012 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.39 |

-0.44 |

-2.67 |

2033 |

| 2013 |

-0.15 |

-0.06 |

0.16 |

-0.05 |

-2.72 |

2033 |

| 2014 |

-0.01 |

-0.06 |

-0.09 |

-0.16 |

-2.88 |

2033 |

| 2015 |

0.02 |

-0.06 |

0.24 |

0.20 |

-2.68 |

2034 |

| 2016 |

0.03 |

-0.06 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

-2.66 |

2034 |

| 2017 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

-0.12 |

-0.17 |

-2.83 |

2034 |

| 2018 |

0.00 |

-0.06 |

0.04 |

-0.02 |

-2.84 |

2034 |

| 2019 |

0.00 |

-0.05 |

0.10 |

0.06 |

-2.78 |

2035 |

| 2020 |

-0.12 |

-0.05 |

-0.26 |

-0.43 |

-3.21 |

2035 |

| 2021 |

-0.01 |

-0.05 |

-0.26 |

-0.32 |

-3.54 |

2034 |

Some commentators cite huge dollar figures that appear in the trustees’ report, such as the $19.8 trillion shortfall over 75 years (or even over the shortfall over the infinite horizon, a measure whose validity many experts question[5]). Except over relatively short periods, however, it is not useful to express Social Security’s income, expenditures, or funding gap in dollar terms, which does not convey a sense of our ability to support the program. Expressing them in relation to taxable payroll or GDP, in contrast, puts them in perspective. Over the next 75 years, for example, taxable payroll will equal $592 trillion, and GDP will be $1,698 trillion.[6] Thus, Social Security’s unfunded liability over the next 75 years — in other words, its shortfall divided by the potential resources available to pay for it — equals 3.4 percent of taxable payroll and 1.2 percent of GDP.[7])

2034 is the “headline date” in the trustees’ report, because that is when the combined Social Security trust fund reserves — that is, the excess contributions it has collected and invested in Treasury bonds over the past three decades — will be depleted. At that point, if nothing else is done, the program could pay 78 percent of scheduled benefits, mostly out of workers’ ongoing contributions, a figure that would slip to 74 percent in 75 years.[8] Contrary to popular misconception, benefits would not stop. [9]

The trustees project that the DI trust fund reserves will last through 2057 — eight years sooner than in last year’s report.[10] Because DI costs and income are in close balance, even small changes can significantly alter the DI trust fund’s projected reserve depletion date. So far, the COVID-19 pandemic has not led to an increase in disability claims, possibly because the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) field offices have been closed since March 2020. In fact, the number of DI applicants and beneficiaries has declined over the past several years, including in 2020. Analysts anticipated this basic trend, since most of the growth in DI enrollment in prior years was due to demographic factors such as the aging of the baby-boom generation, but enrollment has fallen more than expected. As the baby boomers have reached retirement, the number of workers receiving DI benefits has declined for six straight years. Likewise, DI applications, which spiked in the aftermath of the Great Recession, have fallen every year since 2010. The trustees assume that disability claims will increase in the near term, as SSA field offices reopen and as people with significant long-term effects from COVID-19 apply for benefits.

Although the exhaustion dates attract media attention, the trustees caution that their projections are uncertain. For example, while 2034 is their best estimate of when the trust fund reserves will be depleted, they judge there is an 80 percent probability that the reserves will be depleted between 2032 and 2038.[11] The Congressional Budget Office projected that the trust fund reserves would be depleted in 2032.[12] In short, all reasonable estimates show a long-run problem that needs to be addressed but not an immediate crisis.

Following the 1983 Social Security amendments, the trust fund reserves grew dramatically, which has helped to finance the retirement of the baby-boom generation. The principal and interest from the trust funds’ bonds will enable Social Security to keep paying full benefits until 2034. The bonds have the full faith and credit of the United States government, and — as long as the solvency of the federal government itself is not called into question — Social Security will be able to redeem its bonds just as any private investor might do.[13] To do so, the federal government will have to increase its borrowing from the public, raise taxes, or spend less. That will be a concern for the Treasury — but not for Social Security.

Policymakers need to strengthen Social Security. Nearly every American participates in Social Security, first as a worker and eventually as a beneficiary. The program’s benefits are the foundation of income security in old age, though they are modest both in dollar terms and compared with benefits in other countries.[14] Millions of beneficiaries have little or no income other than Social Security.[15]

Because Social Security benefits are so modest and make up the principal source of income for most beneficiaries, policymakers should restore solvency primarily by increasing Social Security’s tax revenues. Added revenues could come from raising the maximum amount of wages subject to the payroll tax (which covered only about 82 percent of covered earnings in 2020,[16] well short of the 90 percent figure envisioned in the 1977 Social Security amendments); broadening the tax base by subjecting voluntary salary-reduction plans, such as cafeteria plans and health care Flexible Spending Accounts, to the payroll tax (as 401(k) plans are); and raising the payroll tax rate by small steps.[17]

Future workers are expected to be more prosperous than today’s. Under the trustees’ assumptions, the average worker will be more than twice as well off in real terms by 2075. It is appropriate to devote a small portion of those gains to the payroll tax, while still leaving future workers with substantially higher take-home pay. Social Security is a popular program, and poll respondents of all ages and incomes have expressed a willingness to support it through higher taxes.[18] Policymakers need to design reforms judiciously so that Social Security remains the most effective and successful income security program.