End Notes

[1] Cecile Murray contributed to this report.

[2] Social Security Administration, “The 2016 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivor’s and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds,” June 22, 2016, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/tr/2016/tr2016.pdf.

[3] Kathleen Romig, “What the 2016 Trustees’ Report Shows About Social Security,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 12, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/what-the-2016-trustees-report-shows-about-social-security. The Congressional Budget Office is somewhat more pessimistic about Social Security’s finances; for more details see Kathy Ruffing, “CBO’s Social Security Projections No Cause for Alarm,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 16, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/cbos-social-security-projections-no-cause-for-alarm.

[4] Kathy Ruffing and Paul N. Van de Water, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Social Security Benefits Are Modest: Policymakers Have Limited Room to Reduce Benefits Without Causing Hardship,” August 1, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/social-security-benefits-are-modest.

[5] It would take at least 20 to 30 years from enactment to net appreciable savings from benefit cuts, so “increasing revenue is almost the only viable short- to medium-tem policy option.” Thomas L. Hungerford, “Broadening the Social Security Tax Base: Issues and Options,” Tax Notes, June 6, 2016, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2853616/Hungerford.pdf.

[6] More than seven in ten registered voters say Social Security benefits should not be reduced in any way, including 68 percent of Republicans and 72 percent of Democrats. (Pew Research Center, “Campaign Exposes Fissures Over Issues, Values and How Life Has Changed in the U.S.,” March 31, 2016, http://www.people-press.org/2016/03/31/3-views-on-economy-government-services-trade/.) More than eight in ten — including 74 percent of Republicans and 88 percent of Democrats — agree that “it is critical to preserve Social Security even if it means increasing Social Security taxes paid by working Americans.” (Jasmine V. Tucker, Virginia P. Reno, and Thomas N. Bethell, “Strengthening Social Security: What Do Americans Want?” National Academy of Social Insurance, January 2013, https://www.nasi.org/sites/default/files/research/What_Do_Americans_Want.pdf.)

[7] Most economists agree that employees bear the true cost of employer payroll taxes in the form of lower wages.

[8] Social Security replaces 90 percent of the first $856 of average indexed monthly earnings (AIME), 32 percent of AIME between $856 and $5,157, and 15 percent of AIME above $5,157, for all earnings up to the tax cap.

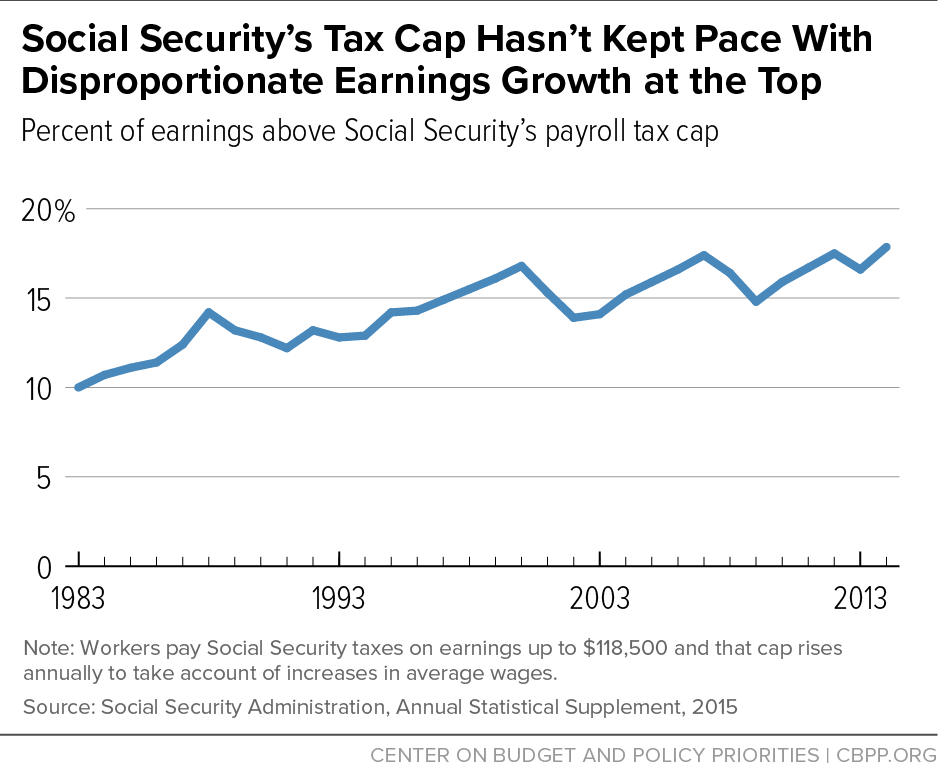

[9] Kevin Whitman and Dave Shoffner, “The Evolution of Social Security’s Taxable Maximum,” Social Security Administration (SSA), Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, September 2011, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/policybriefs/pb2011-02.html.

[10] The 1977 legislation fully phased in the tax cap changes by 1981, after which the cap was indexed to wage growth. In years in which there is no cost-of-living-adjustment for Social Security, the taxable maximum does not increase. See Kathleen Romig, “No COLA for 2016 Will Affect Medicare Premiums and Social Security Finances,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 20, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/no-cola-for-2016-will-affect-medicare-premiums-and-social-security-finances.

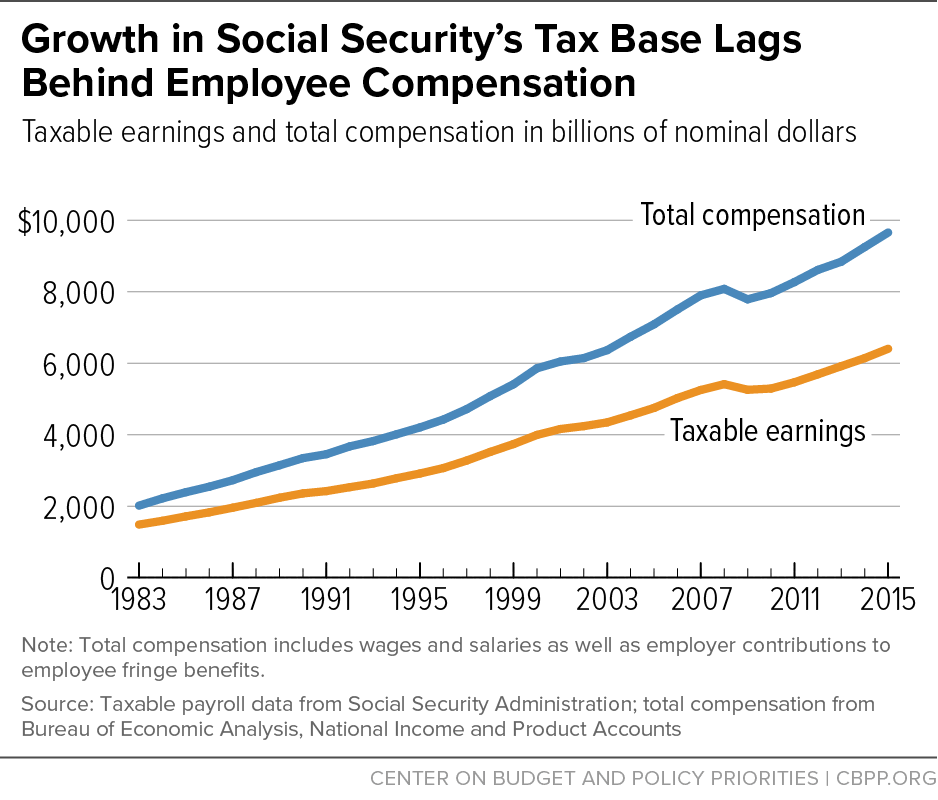

[11] Social Security’s actuaries estimate that 81.77 percent of wages are taxed in 2016 and expects the proportion to rise to 82.50 percent in 2025. CBO projects it will fall below 79 percent. See Kathy Ruffing, “CBO’s Social Security Projections No Cause for Alarm,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 16, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/cbos-social-security-projections-no-cause-for-alarm.

[12] For more information, see Jonathan Gruber, “The Tax Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15766, February 2010, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15766.pdf?new_window=1

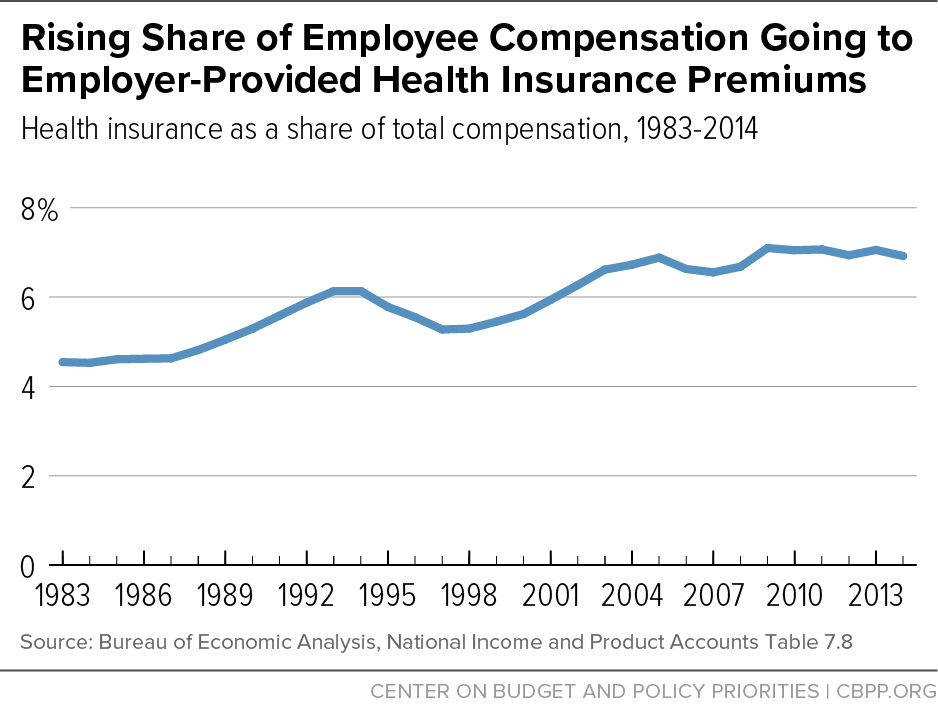

[13] Gary Burtless and Sveta Milusheva, “Effects of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Costs on Social Security Taxable Wages,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 73 No. 1, 2013, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v73n1/v73n1p83.html.

[14] Excluding employer sponsored health insurance premiums from both Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes is estimated to cost $127.5 billion in 2015, and $1.6 trillion over 2016-2025. (See Supplementary Table 14-1 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Analytical_Perspectives.) The Social Security Trustees estimate that the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) taxable payroll is about 25 percent larger than the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) taxable payroll (TR, p. 200), and the rates are different for each tax: 12.4 percent OASDI and 2.9 percent for HI, with an additional 0.9 percent tax on the highest earners. After factoring in the rate and base for each payroll tax, we estimate that Social Security payroll taxes account for about three-quarters of the total payroll tax expenditure.

[15] Thomas L. Hungerford, “Broadening the Social Security Tax Base: Issues and Options,” Tax Notes, June 6, 2016.

[16] This paper analyzes each of these options using solvency and distributional estimates from SSA’s Office of the Chief Actuary and Office of Retirement Policy. For more on the methodology used to produce these estimates, please see https://www.ssa.gov/policy/about/mint.html.

[17] Policymakers could also raise revenues by taxing a greater proportion of Social Security benefits, by taxing new sources of income like investment returns or by increasing the number of people who pay into the program — for example, by covering state and local workers who do not participate in Social Security or through comprehensive immigration reform. Those options are beyond the scope of this paper.

[18] The bipartisan plans that Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles (co-chairs of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform) and Alice Rivlin and Pete Domenici (co-chairs of the Bipartisan Policy Center Debt Reduction Task Force) produced in late 2010 each recommended increasing Social Security’s tax cap.

[19] “Population Profiles: Taxable Maximum Earners,” SSA, ORP, March 2015, https://www.ssa.gov/retirementpolicy/fact-sheets/tax-max-earners.html.

[20] Benjamin I. Page, Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright,

“Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans,” Perspectives on Politics, March 2013, http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~jnd260/cab/CAB2012%20-%20Page1.pdf.

[21] SSA, OCACT, August 2016, “Social Security Contribution and Benefit Bases for 2016-2025 for Current Law and Levels Needed to Achieve 85%, 86%, 87%, and 90% Ratios of Effective Taxable Payroll to Covered Earnings Under the Intermediate Assumptions of the 2016 Trustees Report.”

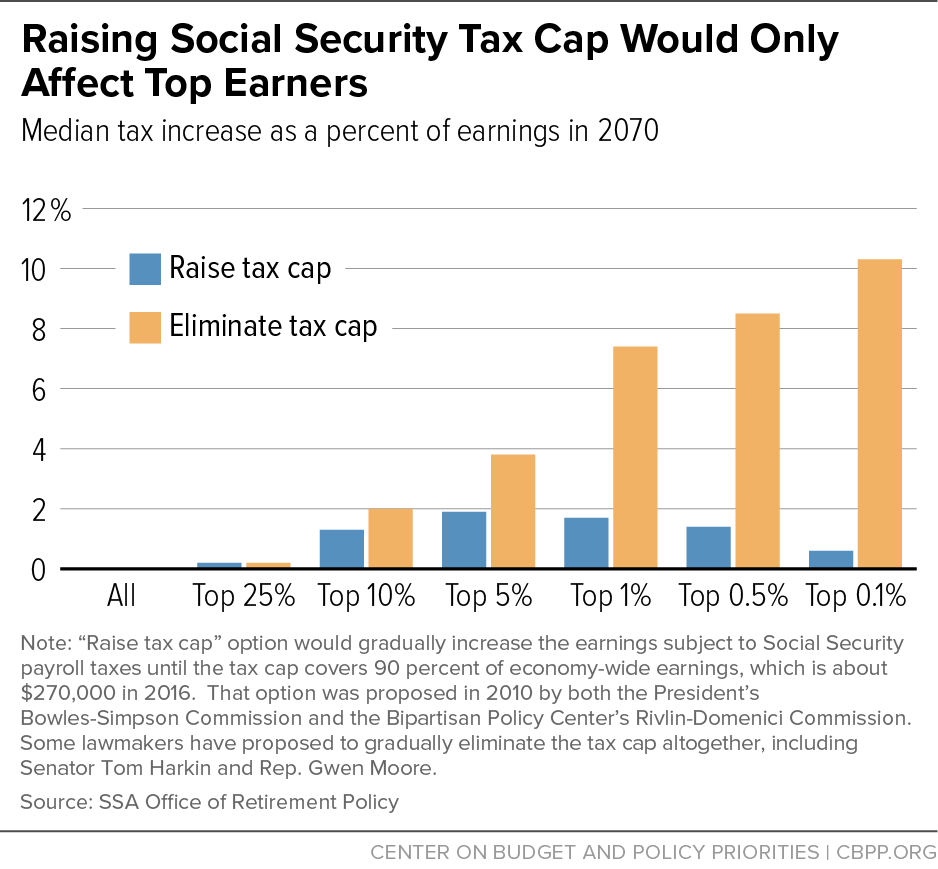

[22] Figure 5 shows the difference between the lifetime present value of payroll taxes paid under each option and under current law, divided by the lifetime present value of taxable covered earnings under current law.

[23] The solvency estimates in this paper, from SSA’s Office of the Chief Actuary, account for shifting compensation away from taxable earnings. The distributions estimates, from SSA’s Office of Retirement Policy, do not.

[23]“Payroll Tax Loophole Used by John Edwards and Newt Gingrich Remains Unaddressed by Congress,” Citizens for Tax Justice, September 6, 2013, http://www.ctj.org/taxjusticedigest/archive/2013/09/payroll_tax_loophole_used_by_j.php#.V9rLgPkrJD8.

[25] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Joel Friedman, “Tax Expenditure Reform: An Essential Ingredient of Needed Deficit Reduction,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 28, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/tax-expenditure-reform-an-essential-ingredient-of-needed-deficit-reduction, and Joel Friedman, Robert Greenstein, and Sharon Parrott, “Key Elements of the President’s Fiscal Year 2015 Budget,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 5, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/key-elements-of-the-presidents-fiscal-year-2015-budget.

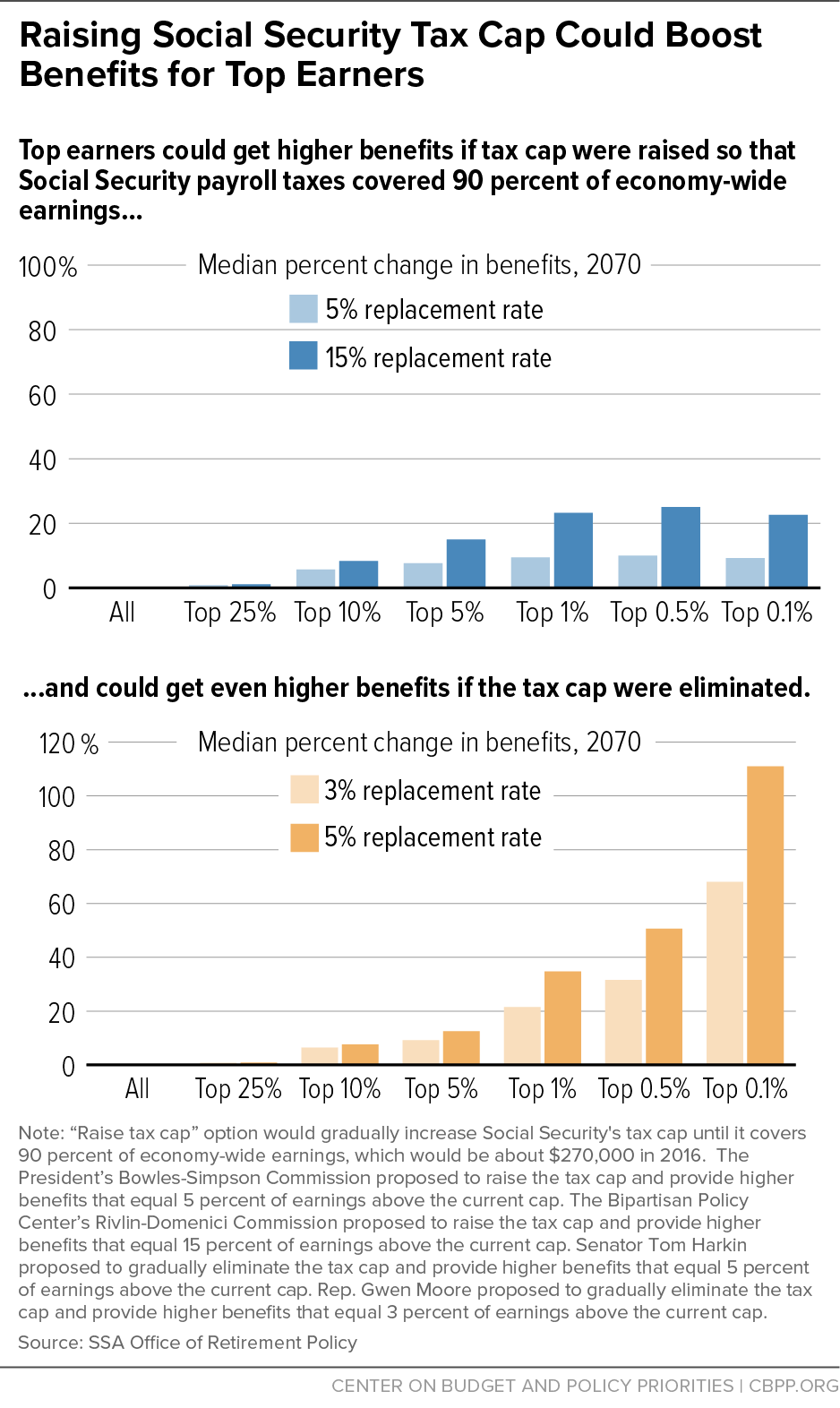

[26] Social Security Expansion Act (S. 731), introduced in 2015, E2.5: https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/BSanders_20150323.pdf

[27] This option would gradually increase the tax cap 2 percent per year beyond current-law indexing, until it covers 90 percent of covered earnings. Any AIME above the current cap would be replaced at a 15 percent rate. SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, Provisions Affecting Payroll Taxes, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/payrolltax.html, E3.5 (beginning in 2017).

[28] Policymakers could also treat any earnings above the tax cap separately, applying a specific replacement rate only to any annual earnings above that year’s tax cap (“AIME+”), instead of the current-law AIME, which measures average earnings over a lifetime. This would limit the benefit increase — and costs — of raising the tax cap.

[29] This option would increase the tax cap 2 percent per year beyond current-law indexing, until it covers 90 percent of covered earnings. Any AIME above the current cap would be replaced at a 5 percent rate. SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, Provisions Affecting Payroll Taxes, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/payrolltax.html, E3.7 (beginning in 2018).

[30] Both the Social Security Enhancement and Protection Act of 2013 (H.R. 1374), introduced by Rep. Gwen Moore, and the Rebuild America Act (S. 2252), introduced by Senator Tom Harkin in 2012, would gradually eliminate the tax cap, by taxing all earnings above the current cap at 1.24 percent in the first year, 2.48 percent in the second, and so on, up to the full 12.4 percent in the tenth year. Any AIME above the current cap would be replaced at a 3 percent rate in the Moore plan and at 5 percent in the Harkin plan. SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, Provisions Affecting Payroll Taxes, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/payrolltax.html, E2.12 and E2.10 (beginning in 2019 and 2018, respectively).

[31] Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population, 2014,” http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/.

[32] Robert Kaestner and Darren Lubotsky, “Health Insurance and Income Inequality,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 30, No. 2, Spring 2016, http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.30.2.53.

[33] The Kaiser Family Foundation found that the number of Americans who purchase insurance on the individual market — including in the marketplaces — grew 46 percent from 2013 to 2014, from 10.6 to 15.6 million. See Larry Levitt, Cynthia Cox, and Gary Claxton, “Data Note: How Has the Individual Insurance Market Grown Under the Affordable Care Act?”, Kaiser Family Foundation, May 12, 2015, http://kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/data-note-how-has-the-individual-insurance-market-grown-under-the-affordable-care-act/.

[34] The provision would gradually expand Social Security-covered earnings to include both employer and employee premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance. Starting in 2020, premiums above the 75th percentile would be subject to the payroll tax, with this gradually expanding until all premiums are taxed in 2030. (This proposal would also cap and phase out the exclusion of employer-sponsored health insurance premiums from income taxes.) SSA, OCACT, Provisions Affecting Coverage of Employment or Earnings, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/coverage.html, F3, based on the provision from the deficit reduction plan that former Office of Management and Budget and CBO director Alice Rivlin and former Senator Pete Domenici developed for the Bipartisan Policy Center.

[35] For a detailed breakdown of how tax and benefit changes would be distributed in the population, see Kathleen Romig, Dave Shoffner, and Kevin Whitman, “Distributional Effects of Taxing Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Premiums for Social Security,” SSA, August 2016, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/policybriefs/pb2016-01.html. The change would affect benefits — which are based on covered earnings — gradually. As workers paid Social Security taxes on their health insurance premiums for more years, their resultant benefits would be higher.

[36] Many lower earners get Medicaid; middle earners are the group receiving the greatest share of its compensation as fringe benefits; some higher earners are shielded by the tax cap.

[37] See “FAQ for Government Entities Regarding Cafeteria Plans,” Internal Revenue Service, https://www.irs.gov/Government-Entities/Federal,-State-&-Local-Governments/FAQs-for-government-entities-regarding-Cafeteria-Plans.

[38] See Table 41 in “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2015,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 2015, http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2015/ebbl0057.pdf.

[39] This provision would expand Social Security-covered earnings to include contributions to voluntary salary reduction plans (such as Cafeteria 125 plans and Flexible Spending Accounts), starting in starting in 2017. SSA, OCACT, Provisions Affecting Coverage of Employment or Earnings, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/coverage.html, F4, based on provision from Rivlin-Domenici commission.

[40] SSA, 2016 Trustees Report, Overview, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/TR/2016/II_A_highlights.html#. In 2034, the 75-year window would include more deficit years than today’s 75-year projection period does.

[41] This provision would increase the payroll tax rate by 0.1 percentage point each year, starting in 2019, until it reaches 13.0 percent in 2024. SSA, OCACT, Provisions Affecting Payroll Taxes, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions /payrolltax.html, E1.8 (based on based on Social Security Enhancement and Protection Act of 2013, H.R. 1374, introduced by Representative Gwen Moore).

[42] This provision would increase the payroll tax rate by 0.1 percentage point each year, starting in 2020, until it reaches 14.8 percent in 2043, where it would stay for 40 years. Then, from 2082 to 2086, the rate would increase 0.1 percentage point each year until it reached 15.3 percent. SSA, OCACT, Provisions Affecting Payroll Taxes, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/solvency/provisions/payrolltax.html, E1.9 (based on H.R. 1391, The Social Security 2100 Act, introduced in 2015 by Representative John Larson).

[43] “Policy Basics: Federal Payroll Taxes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-federal-payroll-taxes.