After Decades of Costly, Regressive, and Ineffective Tax Cuts, a New Course Is Needed

Testimony of Samantha Jacoby, Senior Tax Legal Analyst, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Before the Senate Committee on the Budget

End Notes

[1] Sharon Parrott et al., “McCarthy Bill Uses Debt Ceiling to Force Harmful Policies, Deep Cuts,” CBPP, April 24, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/mccarthy-bill-uses-debt-ceiling-to-force-harmful-policies-deep-cuts.

[2] The most significant tax policy changes enacted under President George W. Bush were the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, often referred to as the “Bush tax cuts” but formally named the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA) and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA).

[3] The Center for American Progress estimates that the Bush and Trump tax cuts combined will have added $10 trillion to the federal debt by the end of 2023, taking into account both the revenue lost and the associated debt service costs since their enactment. See Bobby Kogan, “Tax Cuts Are Primarily Responsible for the Increasing Debt Ratio,” Center for American Progress, March 27, 2023, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/tax-cuts-are-primarily-responsible-for-the-increasing-debt-ratio/.

[4] Emily Horton, “The Legacy of the 2001 and 2003 ‘Bush’ Tax Cuts,” CBPP, updated October 23, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/the-legacy-of-the-2001-and-2003-bush-tax-cuts.

[5] All high-income taxpayers benefited from the creation of a new 10 percent rate at the bottom, and some high-income married couples benefited from the “marriage penalty relief” provision.

[6] Average tax cuts are expressed in 2023 dollars. Tax change is distributed by percentiles of cash income adjusted for family size. These tax cuts include the amount by which the tax cuts increased the cost of raising the threshold for the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Partly due to the Bush tax cuts, the AMT — designed to ensure that higher-income people who take large amounts of deductions and other tax breaks pay at least a minimum level of tax — would have hit a growing number of middle-class taxpayers. See Aviva Aron-Dine and Robert Greenstein, “The AMT’s Growth Was Not ‘Unintended,’” CBPP, November 30, 2007, https://www.cbpp.org/research/the-amts-growth-was-not-unintended. These cuts also include the rebates in the 2008 stimulus package (passed under President Bush), and the initial phasedown of the estate tax through 2010. They do not include the tax provisions of the 2009 stimulus package (passed under President Obama) or the estate tax cuts in 2011 and 2012 that prevented the estate tax from returning to its original level after 2010. Chye-Ching Huang and Nathaniel Frentz, “Bush Tax Cuts Have Provided Extremely Large Benefits to Wealthiest Americans Over Last Nine Years,” CBPP, July 30, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/research/bush-tax-cuts-have-provided-extremely-large-benefits-to-wealthiest-americans-over-last-nine.

[7] Tax Policy Center, “T10-0232 - Current Law; Baseline: Pre-EGTRRA Law; Distribution by Cash Income Percentile, 2010,” September 14, 2010, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/distributional-impact-bush-tax-cuts-2004-2010/current-law-baseline-pre-egtrra-law-12.

[8] Ibid.

[9] This figure is based on a compilation of Congressional Budget Office (CBO) cost estimates that includes both the revenue and outlay effects of all major tax legislation enacted during the George W. Bush Administration. Based on analysis in Kathy Ruffing and Joel Friedman, “Economic Downturn and Legacy of Bush Policies Continue to Drive Large Deficits,” CBPP, February 28, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economic-downturn-and-legacy-of-bush-policies-continue-to-drive-large-deficits. For a detailed description of methodology used in this analysis, see box, “What Did Bush-Era Tax Cuts Cost through 2011?” in Kathy Ruffing and James R. Horney, “Downturn and Legacy of Bush Policies Drive Large Current Deficits,” CBPP, updated October 10, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/research/downturn-and-legacy-of-bush-policies-drive-large-current-deficits.

[10] “Chart Book: The Bush Tax Cuts,” CBPP, December 12, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/research/chart-book-the-bush-tax-cuts.

[11] William Gale and Andrew Samwick, “Effects of Income Tax Changes on Economic Growth,” Brookings Institution, February 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/09_Effects_Income_Tax_Changes_Economic_Growth_Gale_Samwick_.pdf.

[12] Chye-Ching Huang, “Budget Deal Makes Permanent 82 Percent of President Bush’s Tax Cuts,” CBPP, January 3, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/budget-deal-makes-permanent-82-percent-of-president-bushs-tax-cuts.

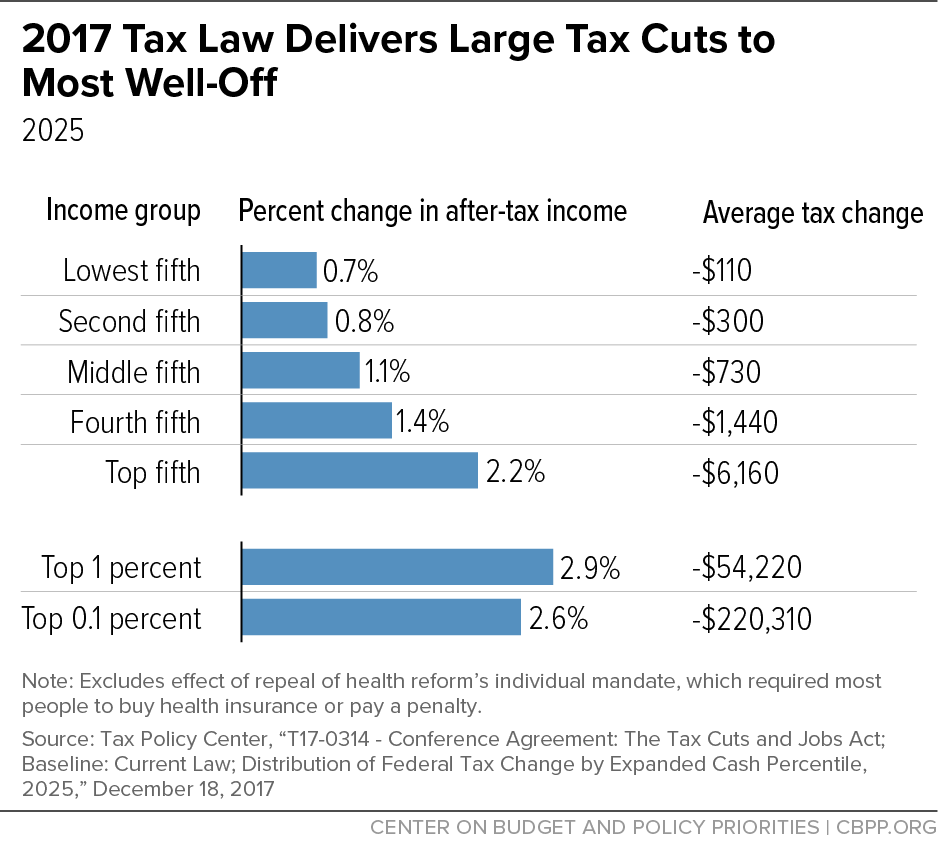

[13] 2025 is when the law is fully phased in and is before many provisions in the law are scheduled to expire. Tax Policy Center, “T17-0314 - Conference Agreement: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act; Baseline: Current Law; Distribution of Federal Tax Changes by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2025,” December 18, 2017, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/conference-agreement-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-dec-2017/t17-0314-conference-agreement.

[14] Due to racial barriers to economic opportunity, households of color are overrepresented at the bottom of the income distribution while non-Hispanic white households are heavily overrepresented at the top. The 2017 tax law’s core provisions tilt heavily toward households at the top of the income distribution: white households in the highest-earning 1 percent receive 23.7 percent of the law’s total tax cuts, far more than the 13.8 percentage share that the bottom 60 percent of households of all races receive. Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity,” CBPP, July 25, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-the-federal-tax-code-can-better-advance-racial-equity.

[15] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,” JCX-67-17, December 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2017/jcx-67-17/.

[16] Tax Policy Center, “T17-0180 - Share of Change in Corporate Income Tax Burden; By Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2017,” June 6, 2017, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/distribution-change-corporate-tax-burden-june-2017/t17-0180-share-change-corporate.

[17] Council of Economic Advisers, “Corporate Tax Reform and Wages: Theory and Evidence,” October 2017, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/Tax%20Reform%20and%20Wages.pdf#:~:text=Using%20conservative%20estimates%20from%20the%20academic%20literature%20on,in%20current%20dollars%20by%20at%20least%20%244%2C000%2C%20conservatively.

[18] Patrick J. Kennedy et al., “The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax: Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” January 20, 2022, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/course/kennedyetal2023TCJA.pdfWhen accounting for the fact that some workers benefit indirectly from equity ownership, the study finds that 78 percent of the overall economic gains accrue to the top 10 percent of the income distribution and just 22 percent flow to the bottom 90 percent. (Breakdowns within the bottom 90 percent are not reported, but equity ownership is highly concentrated toward the top of the income distribution).

[19] Joint Committee on Taxation, op cit.

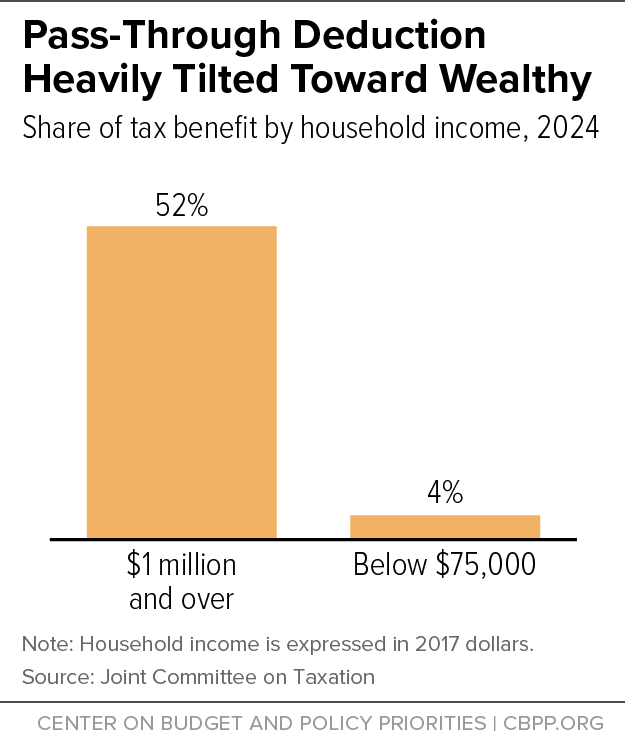

[20] Household income is expressed in 2017 dollars. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 through 2026,” JCX-32r-18, April 24, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2018/jcx-32r-18/.

[21] For example, around 70 percent of the income of partnerships, a common pass-through structure, flows to the top 1 percent of households. Michael Cooper et al., “Business in the United States: Who Owns It, and How Much Tax Do They Pay?” Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2016, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/685594#.

[22] Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2019,” November 15, 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58353.

[23] For example, see Lucas Goodman et al., “How Do Business Owners Respond to a Tax Cut? Examining the 199A Deduction for Pass-through Firms,” NBER Working Paper 28680, November 2022, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28680/w28680.pdf.

[24] Since 2011, the audit rate for partnerships has declined by almost 90 percent, with less than 0.05 percent of partnerships audited in 2019. IRS, “SOI Tax Stats - IRS Data Book,” 2021, Table 17.

[25] Samantha Jacoby, “Repealing Flawed ‘Pass-Through’ Deduction Should Be Part of Recovery Legislation,” CBPP, June 1, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/repealing-flawed-pass-through-deduction-should-be-part-of-recovery-legislation.

[26] Lucas Goodman et al., op. cit.

[27] CBPP, “2017 Tax Law Weakens Estate Tax, Benefiting Wealthiest and Expanding Avoidance Opportunities,” June 1, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/2017-tax-law-weakens-estate-tax-benefiting-wealthiest-and-expanding-avoidance.

[28] See Congressional Budget Office, Budget and Economic Data, 10-Year Budget Projections, Revenue Projections by Category, May 2022, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-05/51138-2022-05-Revenue-Projections.xlsx. This figure does not include the cost of interest payments on the debt from resulting larger deficits.

[29] The law doubled the Child Tax Credit’s maximum value from $1,000 to $2,000 per child but denied millions of children in families with low and moderate incomes the full increase. In tax year 2022, roughly 19 million children get less than the full $2,000 Child Tax Credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes are too low. Tax Policy Center, “T22-0123 – Distribution of Tax Units and Qualifying Children by Amount of Child Tax Credit (CTC), 2022,” October 18, 2022, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/children-and-other-dependents-receipt-child-tax-credit-and-other-dependent-tax. Further, the law was estimated in 2017 to have ended the Child Tax Credit for about 1 million children who weren’t eligible for a Social Security number because of their immigration status but might have been claimed as tax dependents using an Individual Tax Identification Number. CBPP, “2017 Tax Law’s Child Credit: A Token or Less-Than-Full Increase for 26 Million Kids in Working Families,” August 27, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/2017-tax-laws-child-credit-a-token-or-less-than-full-increase-for-26-million.

[30] The 2017 law permanently switched from the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) to the “chained” CPI to adjust tax brackets and certain provisions for inflation each year. The chained CPI generally rises more slowly over time than traditional the CPI-U. This slower growth erodes the value of certain provisions, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, and is expected to push more taxpayers into higher tax brackets over time.

[31] See CBO, Budget and Economic Data, op. cit.

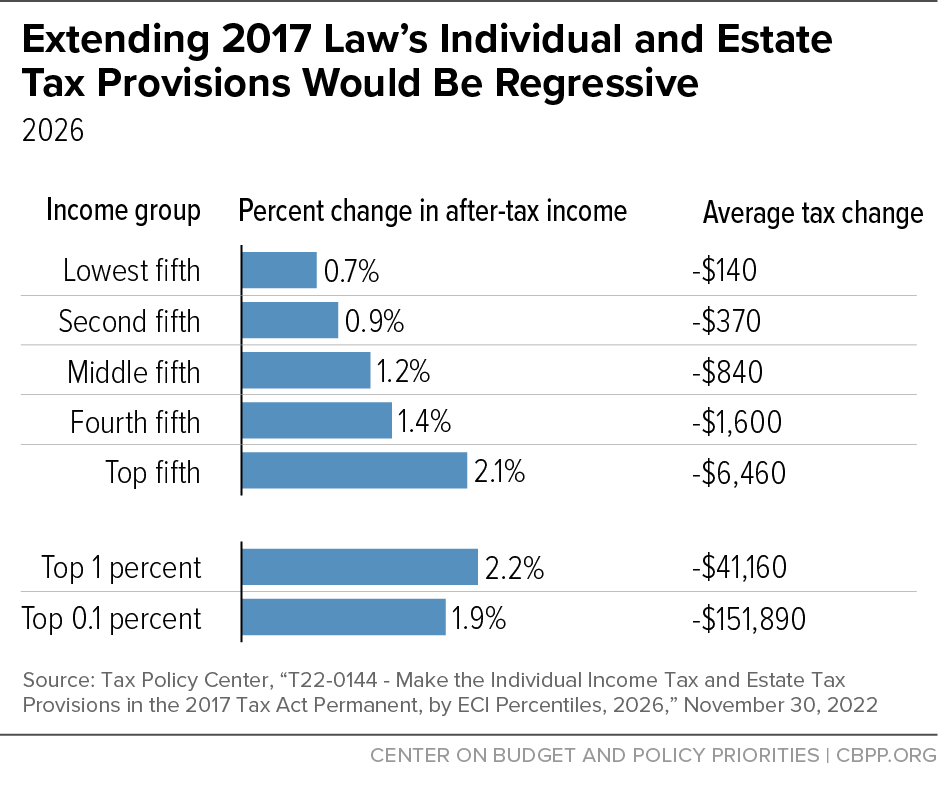

[32] Tax Policy Center, “T22-0144 – Make the Individual Income Tax and Estate Tax Provisions in the 2017 Tax Act Permanent, by ECI Percentiles, 2026,” https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/make-individual-income-tax-and-estate-tax-provisions-2017-tax-act-permanent-1.

[33] Ibid.

[34] CBO, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028,” April 9, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651.

[35] Chuck Marr and Samantha Jacoby, “President Biden’s Budget Charts a Needed Course Correction as 2025 Tax Debate Begins,” CBPP, March 29, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/president-bidens-budget-charts-a-needed-course-correction-as-2025-tax-debate. See CBO, Budget and Economic Data, https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data.

[36] CBO, Budget and Economic Data, op. cit.; Chuck Marr and Samantha Jacoby, “Corporate Lobby’s New Math Doesn’t Add Up for Kids,” CBPP, December 8, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/corporate-lobbys-new-math-doesnt-add-up-for-kids.

[37] Patrick J. Kennedy et al., op. cit.; William Gale and Claire Haldeman, “Searching for supply-side effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Brookings Institution, July 6, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/research/searching-for-supply-side-effects-of-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/.

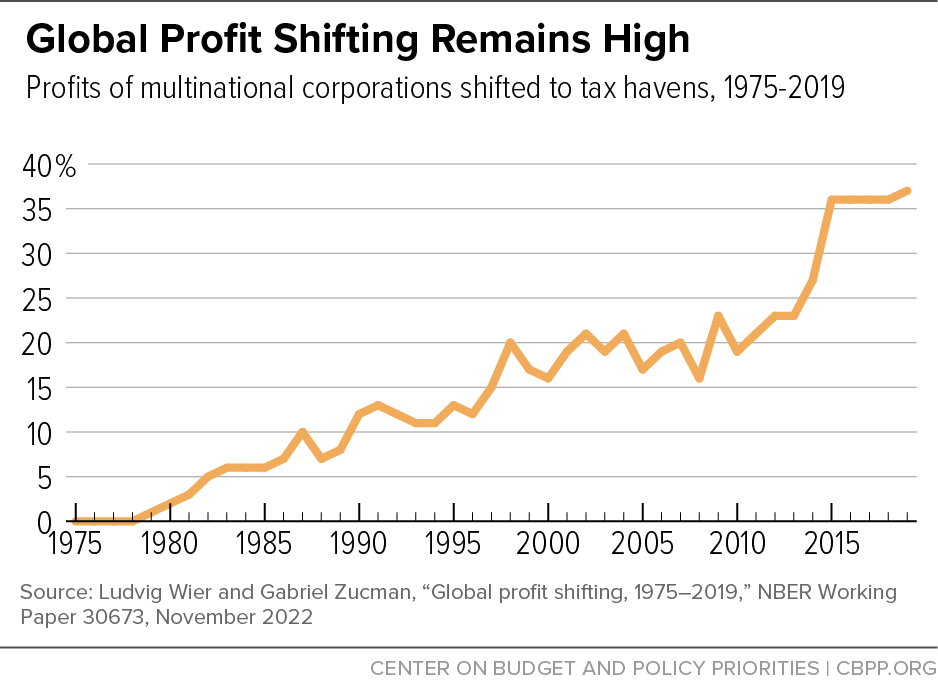

[38] OECD, “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy,” October 8, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-october-2021.htm. See also Samantha Jacoby, “International Tax Reform Proposals Would Limit Overseas Profit Shifting, End ‘Race to the Bottom,’” CBPP, July 11, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/international-tax-reform-proposals-would-limit-overseas-profit-shifting-end.

[39] See Kimberly A. Clausing, Testimony Before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget, April 18, 2023, https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Dr.%20Kimberly%20A.%20Clausing%20-%20Testimony%20-%20Senate%20Budget%20Committee.pdf.

[40] Ludvig Wier and Gabriel Zucman, “New global estimates on profits in tax havens suggest the tax loss continues to rise,” Centre for Economic Policy Research, December 4, 2022, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/new-global-estimates-profits-tax-havens-suggest-tax-loss-continues-rise.

[41] Thomas Tørsløv, Ludvig Wier, and Gabriel Zucman, “The Missing Profits of Nations,” August 10, 2021, https://gabriel-zucman.eu/files/TWZ2021.pdf.

[42] Rebecca Kysar, “US must follow Europe’s lead on global minimum tax — or be left behind,” Financial Times, December 19, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/0e13dbd3-70e6-4733-b546-a50cd9454f8d.

[43] Andrew Barr, Jonathan Eggleston, and Alexander A. Smith, “Investing in Infants: the Lasting Effects of Cash Transfers to New Families,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, April 20, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjac023

[44] According to IRS tax return data, in 2020 the average tax rate for households in the top 0.001 percent of income was 23.73 percent, 2 percentage points lower than the effective tax rate for the top 1 percent as a whole. TPC, “Effective Tax Rate by AGI,” May 8, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/effective-tax-rate-agi. These amounts only include taxable income and therefore exclude unrealized capital gains, which are highly concentrated at the very top of the income distribution. If unrealized gains are included in total income, effective tax rates for the wealthy would be much lower. See Greg Leiserson and Danny Yagan, “What Is the Average Federal Individual Income Tax Rate on the Wealthiest Americans?” September 23, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/09/23/what-is-the-average-federal-individual-income-tax-rate-on-the-wealthiest-americans/.

[45] See Samantha Jacoby, “Biden Proposal Would Eliminate Tax-Free Treatment for Much of Wealthiest Households’ Annual Income,” CBPP, May 6, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/biden-proposal-would-eliminate-tax-free-treatment-for-much-of-wealthiest-households-annual; Jason Furman, “Biden’s Better Plan to Tax the Rich,” Wall Street Journal, March 28, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/bidens-better-plan-to-tax-the-rich-unrealized-capital-gains-assets-treasury-distortion-11648497984?mod=hp_opin_pos_5.

[46] Income and wealth have grown increasingly concentrated at the top of the income distribution in recent decades. See box, “Income, Wealth Are Highly Concentrated and Growing More So,” in Chuck Marr, Samantha Jacoby, and Kathleen Bryant, “Substantial Income of Wealthy Households Escapes Annual Taxation or Enjoys Special Tax Breaks,” CBPP, November 13, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/substantial-income-of-wealthy-households-escapes-annual-taxation-or-enjoys.

[47] Karen C. Burke, “Exploiting the Medicare Tax Loophole,” Florida Tax Review, May 16, 2018, https://journals.upress.ufl.edu/ftr/article/view/639.

[48] For discussions of proposals to tax carried interest as ordinary income, see Steven M. Rosenthal, “Taxing Private Equity Funds as Corporate ‘Developers,’” Tax Notes, January 21, 2013, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/taxing-private-equity-funds-corporate-developers/full; Victor Fleischer, “Two and Twenty Revisited: Taxing Carried Interest as Ordinary Income Through Executive Action Instead of Legislation,” September 18, 2015, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2661623.

[49] Chuck Marr, “Real Estate Tax Breaks, Low-Income Rent Hikes Reflect Skewed Priorities,” CBPP, May 7, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/real-estate-tax-breaks-low-income-rent-hikes-reflect-skewed-priorities.

[50] For example, leading tax scholar Joel Slemrod has noted that “there is no evidence that links aggregate economic performance to capital gains tax rates.” Joel Slemrod, “The Truth About Taxes and Economic Growth,” Challenge, Vol. 46, No. 1, January/February 2003, pp. 5-14, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40722179?seq=1. A Congressional Research Service report finds that cuts in the top capital gains rates since 1945 “have had little association with saving, investment, or productivity growth.” Thomas L. Hungerford, “Taxes and the Economy: Analysis of the Top Tax Rates Since 1945,” Congressional Research Service, December 2012, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R42729.pdf.