- Home

- Federal Tax

- President Biden’s Budget Charts A Needed...

President Biden’s Budget Charts a Needed Course Correction as 2025 Tax Debate Begins

A high-stakes tax debate will begin this year, accelerate through the presidential campaign, and likely culminate with legislative action in 2025. This debate provides an opportunity to correct our course — moving away from the flawed trickle-down path of the 2017 tax law and toward a tax code that raises more needed revenues, is more progressive and equitable, and supports investments that make the economy work for everyone. Putting down an early and important marker, President Biden’s 2024 budget proposes exactly such a course correction.[1]

The President’s budget opposes extending regressive provisions of the 2017 tax law benefitting people making more than $400,000 and supports paying for extensions of provisions affecting people below this threshold with progressive revenue. It also scales back the 2017 law’s egregiously large and permanent tax cuts for corporations and their shareholders and ensures that the wealthiest households pay some income tax each year, while reducing the special breaks they currently receive when they do pay taxes.

The budget then proposes to allocate some of these progressive revenues — generated from reforms that insist that high-income households and profitable corporations pay a more reasonable amount of tax — to pay for key priorities such as expanding the Child Tax Credit, closing the Medicaid coverage gap, helping people afford rent, and making quality child care and pre-K more affordable and accessible. It would also reduce ten-year deficits by nearly $3 trillion.

Making Individual Income and Estate Tax Provisions Permanent Would Be a Costly Mistake

The 2017 tax law’s individual income and estate tax provisions expire beginning in 2026. But more than 70 House Republicans recently introduced a bill that would make them all permanent, and House Budget Committee Chair Jodey Arrington has indicated that the House Republican budget plan will reflect these expiring tax cuts being made permanent.[2] This would be an expensive policy mistake, costing around $2.6 trillion from 2024 to 2033.[3] It would give a roughly $49,000 annual tax cut to the top 1 percent but only about $500 to those in the bottom 60 percent.[4]

In stark contrast, the President “opposes cutting taxes for the wealthy — either extending tax cuts for the wealthy or bringing back tax breaks that would benefit the wealthy.”[5] Moreover, the budget makes clear that extensions of provisions affecting people with incomes below $400,000 should be paid for with progressive revenue.

Indeed, there is a strong case to be made that not all of the tax cuts for people with incomes below this $400,000 threshold should be extended. For example, consider two uses of funding: lowering taxes for households with incomes above $200,000 or $300,000 or using those resources to expand access to affordable child care for families earning less than $50,000.

While households with incomes above $200,000 or $300,000 are not wealthy, they generally are well off enough to afford their monthly expenses and save for future goals. But households with incomes below $50,000 face serious challenges to affording child care, which can exceed $10,000 per year for young children even in middle-cost states.

Expanding access to child care supports child development, parental employment, and household budgets that can be strained to the point where they can’t afford the basics. Households with incomes of $200,000 or $300,000 have a stronger claim on help through the tax code than multi-millionaires, but the nation faces a significant investment deficit and closing it is critical to expanding opportunity.

Budget Calls for Two Key Steps to Creating a Better Tax System

The President’s budget also highlights two important steps to help create a tax system that collects more revenues and requires that high-income households and wealthy corporations who benefit the most from our economy pay a more reasonable amount of tax.

Reforming The 2017 Tax Law’s Costly and Regressive Corporate Provisions

The budget reconsiders the 2017 law’s permanent provisions that are heavily tilted in favor of large corporations and their shareholders, who are disproportionately wealthy. The Biden budget would partially reverse the deep cut in the corporate tax rate, raising it to 28 percent, or halfway between the pre-2017 law 35 percent rate and the current 21 percent rate, acknowledging that the deep cut in the corporate tax rate cost significant revenue without a clear economic benefit for employees.

The budget also calls for Congress to adopt changes to update the international tax rules — which the 2017 law modified but left significant room for profit shifting — to align with the global minimum tax agreement, which Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen played a lead role in negotiating on behalf of the Administration. During congressional negotiations leading up to the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the corporate lobby argued that the U.S. shouldn’t implement the deal before other countries, but this argument is now moot.

The European Union has reached unanimous agreement to implement the 15 percent global minimum tax, which could begin in 2024, with other large economies, including the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Japan, also making progress toward implementation. If the U.S. fails to enact these changes, U.S. companies could end up paying higher taxes to foreign governments — revenues that the U.S. government would have collected had it imposed a reformed minimum tax.

Republican lawmakers made a policy mistake in 2017 by singling out the law’s corporate provisions for permanence. Given their expense, their failure to deliver on promises made, and choices made by other countries, policymakers should not repeat this mistake by exempting these provisions from reconsideration in the debate around the expiring provisions of the 2017 tax law.

Ensuring That More Income of Very Wealthy People Faces Annual Taxation, Reducing Special Breaks

With its 25 percent minimum tax on multimillionaires, President Biden’s budget addresses the deepest flaw of the individual income tax code: the wealthiest people in the country often pay little or no income tax on much of their income each year.

The individual income tax is the nation’s primary federal tax, raising roughly half of federal revenues. For most of the income spectrum, the progressive individual income tax generally works as it should, with higher-income households paying a larger share of their incomes in tax than households with lower incomes.

But this relationship often breaks down at the very top because of the large tax advantages for capital gains, or increases in the value of assets, such as stocks and real estate, which disproportionately benefit wealthy households. First, a special low tax rate applies to realized capital gains — that is, when assets are sold. Even more significantly, unrealized capital gains, a primary source of income for many of the country’s richest people, are not taxed annually and may never face income taxes if the underlying assets are never sold.

The budget’s proposed 25 percent minimum tax would rightly treat these unrealized gains as income for people with assets of more than $100 million. As Martin Sullivan, chief economist of Tax Analysts, recently noted, “among tax economists, it is widely accepted that the income tax base should — as much as possible — equal economic income, which can be defined as consumption plus changes in wealth. Unrealized gain is a change in wealth.”[6] That is, unrealized gains are income that should be taxed.

President Biden’s proposed minimum tax would be paid over several years — essentially a down payment on future tax owed when assets are sold or after the owner’s death. Spreading out the payments in this way would help mitigate concerns about wealthy taxpayers who have large gains in one year and losses the next: if a taxpayer later has a large unrealized loss, those losses will also be spread out over several years and future tax payments will be reduced by the amount of the losses, with refunds paid to taxpayers who have no tax payments to offset. Another design feature would allow taxpayers who primarily own certain types of illiquid assets to defer tax (with a charge akin to interest) until they sell assets. The proposal would raise $437 billion over ten years.

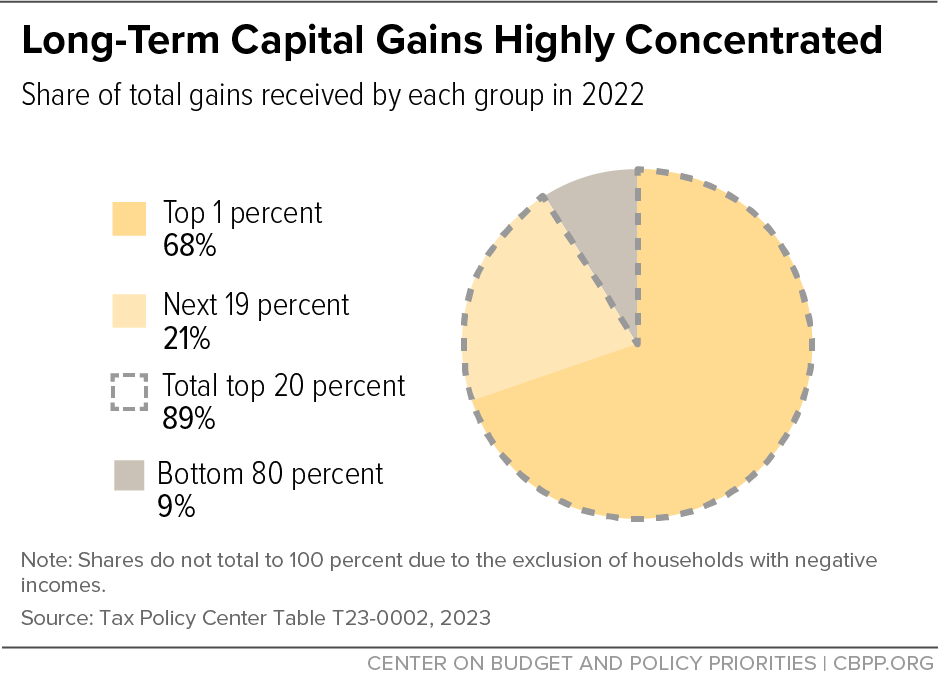

High-income households enjoy special tax breaks even when their income is counted on their tax returns. The budget advances a series of important proposals to reduce some of these special breaks. It proposes to tax income from capital gains and dividends — which are highly concentrated at the top (see Figure 1) — at the same rates as wage and salary income. It would also close several loopholes, including those allowing certain pass-through business owners to avoid a 3.8 percent Medicare tax that others pay, private equity executives to treat their compensation from carried interest as capital gains, and real estate developers to avoid capital gains tax even when they sell buildings and receive profits.

These proposed reforms to the corporate and high-income provisions of the tax code — beyond considerations of the 2017 law provisions that are scheduled to expire — belong at the center of the coming tax debates. They would generate substantial progressive revenue that the U.S. could use to fund key national priorities such as an expanded Child Tax Credit and policies to make health care and housing more affordable.

The President’s budget is a critical opening marker for a broad and robust debate leading up to the 2025 expirations of the 2017 tax law’s provisions. That debate should weigh which provisions should expire, how corporate and high-income provisions should be reformed, how to ensure the wealthiest people in the country pay a reasonable amount of individual income taxes each year, and what national priorities those funds should pay for.

President Biden’s 2024 Budget Moves Us Toward Nation Where Everyone Can Thrive

Policy Basics

Federal Tax

End Notes

[1] Sharon Parrott, “President Biden’s 2024 Budget Moves Us Toward Nation Where Everyone Can Thrive,” CBPP, March 9, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/press/statements/president-bidens-2024-budget-moves-us-toward-nation-where-everyone-can-thrive.

[2] Lindsey McPherson, “Balanced Budget Takes a Backseat to Paring Spending to ’22 Levels at GOP Retreat,” Roll Call, March 20, 2023, https://rollcall.com/2023/03/20/balanced-budget-takes-back-seat-to-paring-spending-to-22-levels-at-gop-retreat/.

[3] CBPP analysis of the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) May 2022 estimates of the effects of extending the 2017 tax law’s expiring individual and estate tax provisions over the 2023-2032 period, adjusted to account for the current ten-year budget window and CBO’s February 2023 budget and economic projections. See CBO, Budget and Economic Data, https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data.

[4] Tax Policy Center, Table T22-0144, “Make the Individual Income Tax and Estate Tax Provisions in the 2017 Tax Act Permanent, by ECI Percentiles, 2026,” https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/make-individual-income-tax-and-estate-tax-provisions-2017-tax-act-permanent-1.

[5] Office of Management and Budget, “Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2024,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/budget_fy2024.pdf.

[6] Martin Sullivan, “Are the Superrich Burdened and Paying the Highest Rates?” Tax Notes, March 13, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-federal/individual-income-taxation/are-superrich-more-burdened-and-paying-highest-rates/2023/03/13/7g494.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: