President Biden’s recovery proposals — including both the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan — would take important steps toward requiring wealthy households and profitable corporations to pay a fairer amount of tax. These changes would begin restoring the nation’s eroded revenue base so it can support the needs of a 21st century economy and start addressing long-standing economic and racial disparities that COVID-19 and the economic fallout exacerbated and highlighted. Policymakers, however, should go further by also repealing the 2017 tax law’s flawed “pass-through” deduction in recovery legislation they enact this year.

The 2017 law included a 20 percent deduction for certain income that owners of pass-through businesses — such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships — report on their individual tax returns, which previously was generally taxed at the same rates as labor income (income from work, such as wages and salaries). The deduction lowers the marginal income tax rate on qualifying pass-through business income well below the top rate on labor income.

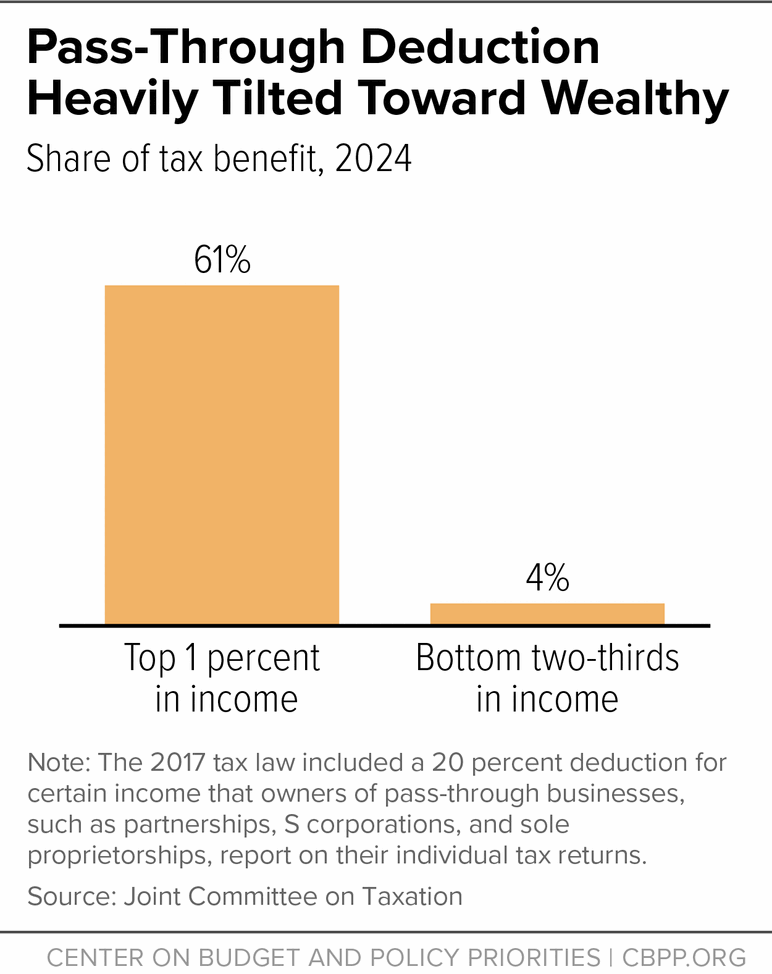

Repeal would raise significant progressive revenue. The deduction costs roughly $50 billion a year through 2025 (when it is scheduled to expire, along with other provisions of the 2017 tax law) and its benefits are heavily tilted towards the wealthy; around 61 percent of its benefits will go to the top 1 percent of households in 2024, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).[1] Wealthy households benefit the most because they receive most of the pass-through income, they get a much larger share of their income from pass-throughs than the middle class does, and they receive the largest tax break per dollar of income deducted (since they are in the top income brackets). President Biden’s proposal during the campaign to phase out the deduction for households with more than $400,000 in income would raise $143 billion over ten years, almost exclusively from the top 1 percent, the Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimated.[2]

Repeal would reduce abuse and improve tax compliance. The pass-through deduction adds significant complexity to the tax code and introduces arbitrary distinctions between different industries and different kinds of income, resulting in vastly different tax rates with little rationale. (For example, independent contractors are often eligible for the deduction but employees aren’t.) This arbitrariness creates a significant gaming opportunity: loopholes in the law allow high-income people to secure large tax savings by converting their labor income into pass-through business income to exploit the deduction. In reality, about three-quarters of high earners’ pass-through income is a form of labor income, a 2019 study found, which means it should be taxed at ordinary income tax rates.[3]

Moreover, pass-through noncompliance — most often through underreporting business income to the IRS — is the single largest source of the nation’s tax gap (the gap between what taxpayers owe and what they pay voluntarily), IRS data from 2011-2013 show.[4] Nevertheless, following massive cuts in IRS funding, audit rates for S corporations and partnerships have fallen by more than 40 percent since 2010 (to just 0.2 percent). The pass-through deduction has likely made it even harder for the IRS to police pass-through tax evasion: the combination of an under-resourced IRS and a tax provision rife with opportunities for abuse invites wealthy individuals and profitable businesses to cross the line between legal tax avoidance and illegal tax evasion.

For these reasons, tax law and policy experts have widely criticized the deduction. Former JCT Chief of Staff Edward Kleinbard termed it “Congress’ worst idea ever.”[5] New York University Law School Professor David Kamin (now deputy director of the White House National Economic Council) described it as “the very worst kind of tax policy, picking winners and losers haphazardly in a complex tax provision, and then generating significant incentives for people to rearrange their businesses to try to get on the right side of the line.”[6] NYU Law Professor Daniel Shaviro wrote that the deduction directs “economic activity away from some market sectors and towards others, for no good reason and scarcely even an articulated bad one.”[7]

Repeal would complement President Biden’s corporate tax proposals. Recognizing that corporations operating in this country derive significant benefits from the federal government’s investments in infrastructure, education, and research and development, the President’s American Jobs Plan would raise the corporate income tax rate to help finance those investments. Like corporations, pass-through businesses benefit greatly from these federal investments; asking high-income pass-through owners to pay more to fund them is appropriate and would help create a more equitable nation.

The President’s American Families Plan would limit some special tax benefits for pass-through businesses; specifically, it would eliminate a major loophole that lets high-income pass-through owners avoid a 3.8 percent Medicare tax and would permanently limit the losses that high-income business owners can deduct from their non-business income, such as capital gains. Policymakers should complement those changes by also repealing the pass-through deduction in recovery legislation this year.

The pass-through deduction effectively cuts the marginal individual income tax rate on pass-through income by 20 percent. While the 2017 law’s proponents often identify small businesses as the intended beneficiaries, the deduction is heavily tilted to the wealthy and big business: 61 percent of its benefits will go to the top 1 percent of households in 2024, JCT estimates.[8] A mere 4 percent will go to the bottom two-thirds of households. (See Figure 1.)

This regressive impact is baked into the deduction’s basic structure, for three reasons:

- Most pass-through income flows to the very highest-income people and to very large businesses. For example, around 70 percent of the income of partnerships, a common pass-through structure, flows to the top 1 percent of households.[9] Many large, profitable businesses are structured as pass-throughs — including financial firms such as hedge funds and private equity firms, real estate businesses, oil and gas companies, and large multinational law and accounting firms — and they generate most pass-through income.

- High-income households get a much larger share of their income from pass-throughs than the middle class does. The top 1 percent of households get around 23 percent of their income from pass-throughs, compared to less than 6 percent for the middle 60 percent of households.[10]

- High-income households enjoy a larger tax break per dollar of deductions because they are in higher tax brackets. For example, under current law, each dollar deducted saves up to 37 cents of tax for a multi-millionaire in the 37 percent bracket, but only up to 22 cents for a small business owner in the 22 percent bracket.

Repealing the deduction would therefore be highly progressive. It also would raise significant revenue. (Though the deduction and some other parts of the 2017 tax law are slated to expire after 2025, supporters of the law say they plan to push for extending them.) President Biden’s proposal during the campaign to phase out the deduction for households with more than $400,000 in income would raise $143 billion over ten years, almost exclusively from the top 1 percent, TPC estimated.[11] Full repeal could raise around $90 billion more, primarily from those with incomes over $200,000, based on JCT estimates.[12]

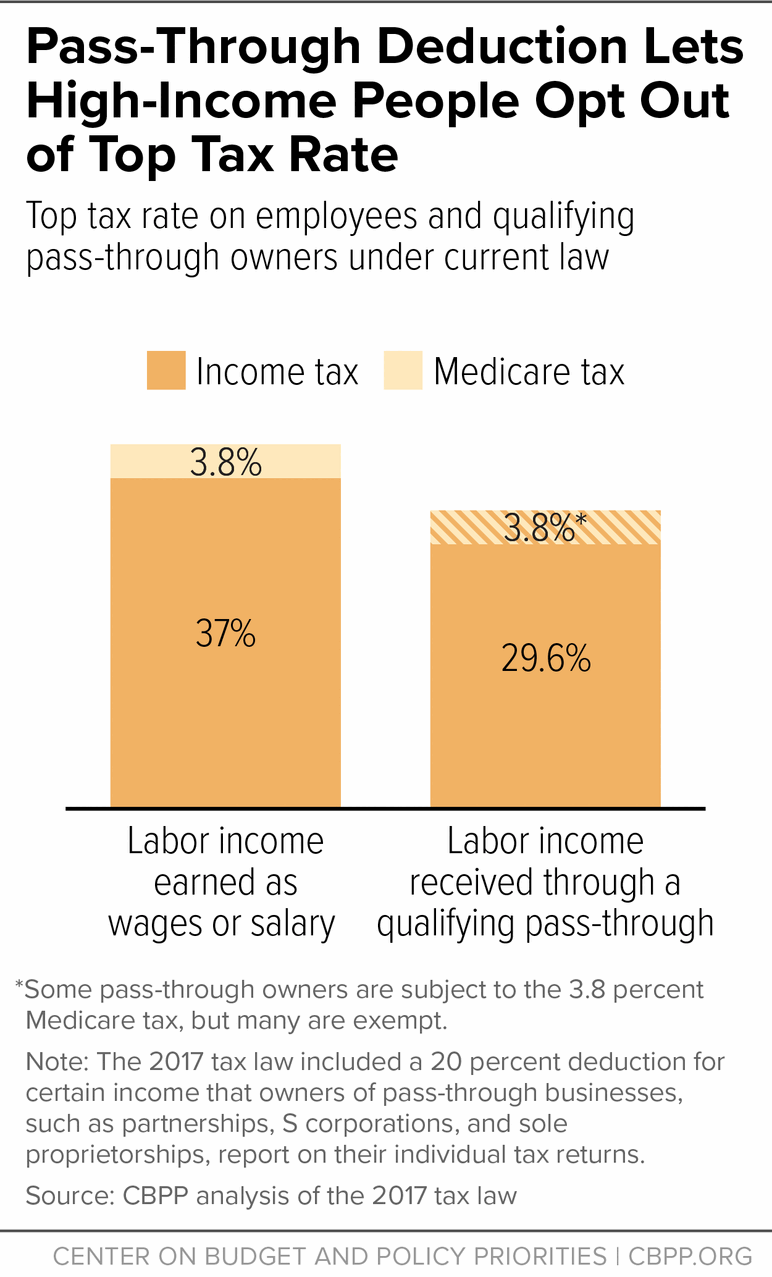

Repealing the pass-through deduction would not only ensure that the same tax rates apply to similar types of income, but also limit a significant gaming opportunity: the ability of wealthy people to generate very large tax savings by converting their labor income into pass-through business income to take advantage of the deduction. The deduction effectively sets up a two-tiered system in which high-income people can legally opt out of the top tax rate if they receive part of their income through a pass-through entity.

Consider two engineers who do similar work and receive the same amount of income, but one is an employee of a company and the other is a co-owner (or partner) of a partnership. The employee of the engineering firm is paid wages subject to ordinary income and payroll taxes, at a combined top tax rate of 40.8 percent under current law. The partner’s income, in contrast, constitutes business profits that could qualify for the pass-through deduction, for a total top rate of 33.4 percent; and the partner might be able to lower the top rate even further to 29.6 percent by avoiding the 3.8 percent Medicare tax that applies to top wages and salaries.[13] (See Figure 2.) Thus, the deduction allows many high-income individuals who receive income through a pass-through entity to secure very large tax savings on their labor income.

The American Families Plan would raise the top marginal income tax rate to 39.6 percent (the rate before the 2017 law) and repeal some tax preferences for some high-income pass-through owners. In particular, it would close the loophole noted above that lets certain high-income pass-through business owners avoid the 3.8 percent Medicare tax on high-income households. Nevertheless, by leaving the pass-through deduction intact, the plan would allow high-income pass-through owners to pay a rate that is 7.9 percentage points below the rate on top wages and salaries.[14]

There is no good justification for taxing pass-through business income at a lower rate than wages and salaries. Indeed, much pass-through income is economically similar to wages and salaries: a 2019 study found that, on average, about three-quarters of high earners’ pass-through income is due to their labor, rather than their capital.[15] For example, consider several business partners who form a pass-through business to develop real estate projects. Each partner might invest a small amount of capital to help get the business off the ground, but they also provide labor, such as meeting with potential investors, finding potential sites, obtaining licenses and permits, and hiring contractors. The eventual profits will partly reflect their initial capital investment, but a much larger share will reflect their labor.

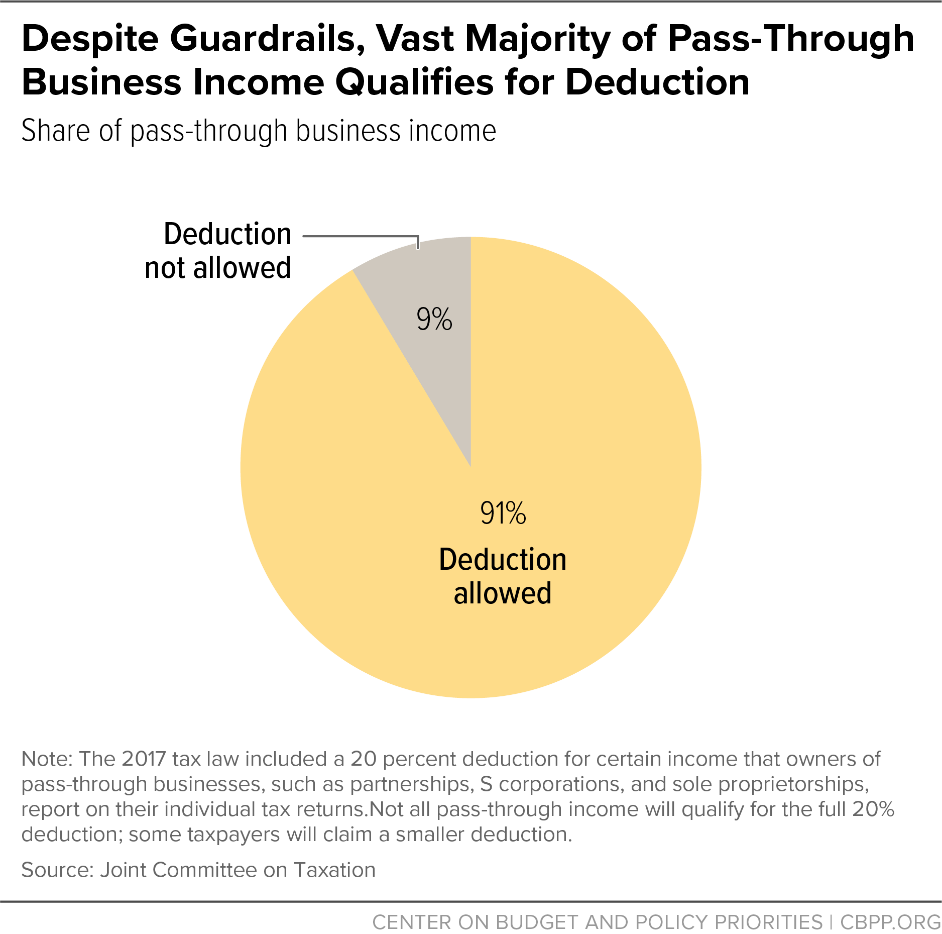

The pass-through deduction includes complex “guardrails” ostensibly aimed at limiting owners’ ability to claim the deduction on their labor income in this way. But JCT estimates that more than 91 percent of pass-through business income will qualify for the deduction even with the guardrails[16] (see Figure 3), and flaws in the guardrails could allow even more income to qualify. (See box, “Flawed Guardrails Can’t Prevent Gaming of Pass-Through Deduction.”)

The guardrails consist of a series of questions for taxpayers to determine whether particular income qualifies for the deduction, with each question drawing a line between qualification and disqualification. (Among other things, the questions draw lines between compensation and profits, between different types of services, and between real estate investment trusts and other assets.) This creates an incentive for wealthy pass-through owners, aided by their accountants or lawyers, to try to place themselves on the tax-saving side of each line in order to claim the deduction for income that should be taxed at ordinary income rates. This gives owners an unfair tax advantage over employees and encourages them to shift even more of their labor income into pass-through businesses.

The current rules’ arbitrariness and potential for abuse weaken the integrity of the entire income tax and add new burdens to an already under-resourced IRS, which has suffered deep funding cuts since 2010.[17] Tax noncompliance by pass-through businesses — in particular, underreporting of income — is the single largest source of the nation’s tax gap.[18] The IRS has estimated, for example, that sole proprietors misreport a staggering 56 percent of their income,[19] and new research from IRS and outside economists suggests that wealthy households’ use of pass-through businesses to illegally evade taxes is even greater than previously assumed.[20] Complex and lucrative provisions like the pass-through deduction create an additional incentive for well-resourced taxpayers to push the boundary between lawful tax avoidance and unlawful tax evasion; and the IRS budget cuts, which have greatly weakened the agency’s audit capacity, give them even more leeway to do so.[21] The American Families Plan includes a strong, two-pronged proposal that would provide multi-year funding for IRS enforcement and expand information reporting for income that tends to be underreported, but policymakers could bolster this effort by repealing the pass-through deduction to eliminate a major loophole in the tax code.

The 2017 tax law included several “guardrails” to prevent high-income people’s labor income from qualifying for the pass-through deduction.a But like many other parts of the hastily drafted law, the guardrails fall well short of their intended goal. They generally won’t stop wealthy taxpayers from gaming the deduction — through both legal tax avoidance and illegal tax evasion — to avoid paying the top tax rate on their labor income. The flaws include:

- Inconsistent exclusion for service businesses. The 2017 law excludes certain high-income owners of “specified service businesses” — such as law, health, and financial services — from claiming the deduction. But it provides little justification for excluding these businesses but not others, and the rules leave so much room for interpretation that different accounting firms often offer conflicting conclusions for the same client.b Moreover, Treasury regulations implementing the law allowed several types of businesses to qualify for the deduction — such as real estate brokers, insurance brokers, and banks — but not other types of brokers and financial professionals.c

- Inadequate restrictions on independent contracting. Independent contractors can often claim the deduction but employees can’t. Employees who become independent contractors of the same business must prove to the IRS that they really are independent contractors in order to receive the deduction, but some employees (especially those with high incomes) could still benefit from the deduction by hiring tax advisors to plan around the rules, even if their income comes from their labor and should therefore be taxed at ordinary income rates. The deduction may also encourage firms to break themselves into pieces so that supervisors could become business owners and thereby qualify for the deduction.d

- Weak wage and property guardrail. For high-income people, the deduction is limited to the greater of 50 percent of the wages the business pays to employees or 25 percent of wages plus 2.5 percent of the cost of the business’s property.e But this guardrail likely isn’t a significant limitation for most pass-throughs. Even when the guardrail does apply, high-income taxpayers might be able to get around it. For instance, while someone who leaves their job to become an independent contractor might see their deduction limited if they have no employees and thus no wages beyond what they pay themselves, they can increase their deduction by paying themselves higher wages. (Amounts paid as wages do not qualify for the deduction, however.)

a In its “Blue Book” (a comprehensive technical description) on the 2017 tax law, JCT noted that “[t]reating corporate and noncorporate business income more similarly to each other under the Federal income tax requires distinguishing labor income from capital income in a noncorporate business.” That is, an across-the-board rate cut for pass-through businesses would unfairly cut taxes on the owners’ labor income. Joint Committee on Taxation, “General Explanation of Public Law 115-97,” December 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5152.

b Eric Yauch, “Whether a Taxpayer Qualifies for 199A Depends on Who You Ask,” Tax Notes, April 11, 2019, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today/exemptions-and-deductions/whether-taxpayer-qualifies-199a-depends-who-you-ask/2019/04/11/29c4h.

c Samantha Jacoby, “Pass-Through Deductions Reflect Industry Lobbying,” CBPP, January 30, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/pass-through-deduction-regulations-reflect-industry-lobbying.

d Brendan Duke, “Pass-Through Deduction in 2017 Tax Law Could Weaken Wages and Workplace Standards,” CBPP, December 19, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/pass-through-deduction-in-2017-tax-law-could-weaken-wages-and-workplace.

e For example, the owner of a firm with $1 million in profits can receive the full 20 percent deduction — worth $200,000 — if the firm pays at least $400,000 in wages.

The American Jobs Plan proposes roughly $2 trillion of infrastructure, research and development, and other investments, financed over 15 years by raising the corporate income tax rate from 21 to 28 percent and making other corporate tax reforms. These changes would begin restoring the nation’s eroded revenue base so it can support the needs of a 21st century economy that broadens opportunity, supports workers and those out of work, and ensures health care for everyone.

Corporations operating in the United States derive considerable benefit from the federal government: they rely on our roads, airports, and ports to move their goods and employees, and they benefit from the large spillover effects of government-funded research and development.[22] Asking profitable corporations to pay more for these services and investments that broaden opportunity is appropriate and would help create a more equitable nation.

The same holds true for pass-through businesses, which account for around half of all U.S. business income.[23] Accordingly, it is reasonable to ask high-income pass-through owners — like shareholders of profitable corporations and high-income wage earners — to pay a fairer amount of tax. Furthermore, with the pass-through deduction, a business that regularly distributes profits to its owners generally pays a lower tax rate than a similar business structured as a corporation.[24] Rolling back the deduction would complement a corporate rate increase and avoid more lopsided tax advantages for pass-through business owners relative to corporations.