BEYOND THE NUMBERS

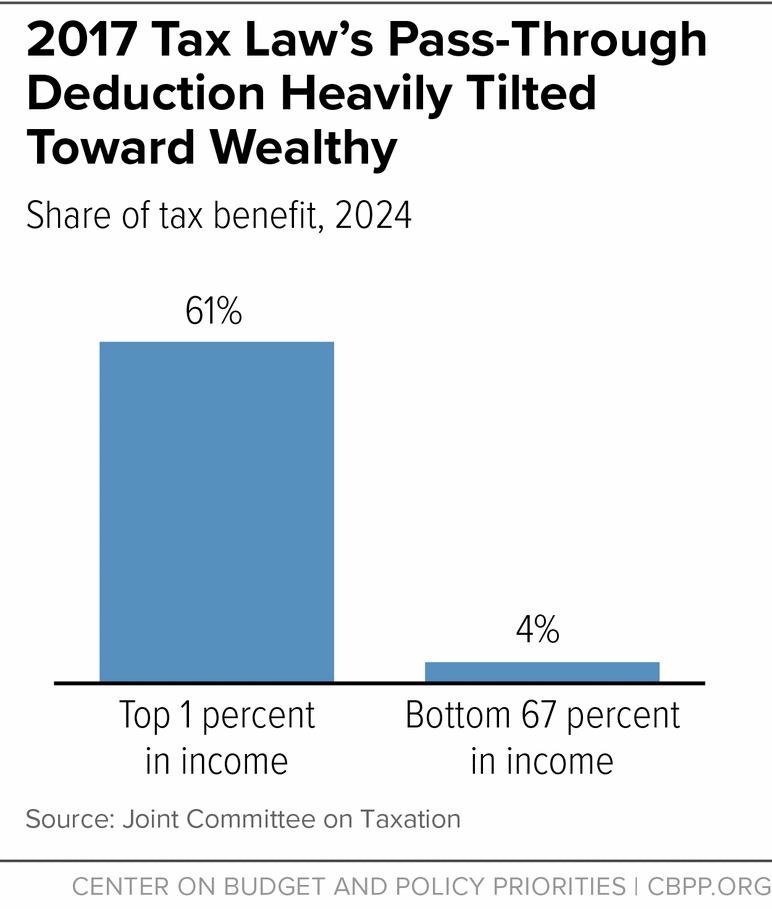

Some 61 percent of the benefit from the 2017 tax law’s 20 percent deduction for pass-through income will flow to the top 1 percent of households in 2024, compared to just 4 percent for the bottom two-thirds, we estimate based on new and earlier estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). (See chart.)

This deduction — like the law in general — has three fundamental flaws: it disproportionately benefits the wealthy, is fiscally irresponsible, and invites rampant tax gaming. The new JCT estimates confirm just how skewed to high-income filers the deduction is.

The law provides a 20 percent deduction on certain “pass-through” income — income that the owners of businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships report on their individual tax returns and that, before this new law, was taxed at the same individual tax rates as an individual’s other ordinary income.

This tax benefit is skewed to the wealthy, as the JCT estimate shows, because pass-through income is heavily concentrated at the top, that income makes up a larger share of wealthy people’s income, and each dollar of the deduction is worth more as a tax break for high-income people as they face the highest individual tax rates. Further, under the 2017 tax law, pass-through owners benefit not only from the 20 percent deduction, but also from the reduction in individual income tax rates. The top rate falls from 39.6 percent to 37 percent under the new law, and so with the 20 percent deduction the top rate on certain pass-through income is now only 29.6 percent.

To put the pass-through deduction, and the law itself, in context, income has shifted dramatically upward in recent decades as wages have been close to stagnant for many working families while income has risen sharply at the top. The share of household income flowing to the bottom 60 percent fell by 4 percentage points from 1979 to 2014, while the share flowing to the top 1 percent rose by 6 percentage points, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The pass-through deduction is a prime example of how the new law further shifts income upward. The top 1 percent will enjoy a share of the benefits from this deduction that’s more than 15 times as large as that which the bottom 67 percent will receive.

It’s also expensive. By 2021, it will cost more than $50 billion a year. (Like other elements of the law, it is set to expire after 2025, though Republican lawmakers say they want to make it permanent without offsetting the cost.)

The provision is the antithesis of tax reform. Instead of improving economic efficiency, it invites wealthy people, who can afford high-priced accountants and lawyers, to restructure their finances strictly for tax — not business — purposes. For example, many may try to convert wage and salary income into pass-through profits to take advantage of the deduction. New York University law professor Daniel Shaviro described it as “the worst provision ever even to be seriously proposed in the history of the federal income tax.”