Chairman Himes, Ranking Member Steil, and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am Sharon Parrott, President of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D.C.

This testimony will make three main points. First, the nation’s economic security programs have made tremendous progress over the past 50 years in reducing poverty and advancing equity, but significant gaps in our policies remain, keeping poverty and hardship far higher than they should be. Second, policymakers shored up economic security policies during the pandemic, achieving historic gains against poverty and lowering hardship despite the twin economic and health crises caused by the pandemic. Third, by building on the experiences of the last two recessions and the strong research base for a number of policies, policymakers should make the investments needed to address economic and health insecurity and glaring disparities in hardship and opportunity across lines of race and ethnicity.

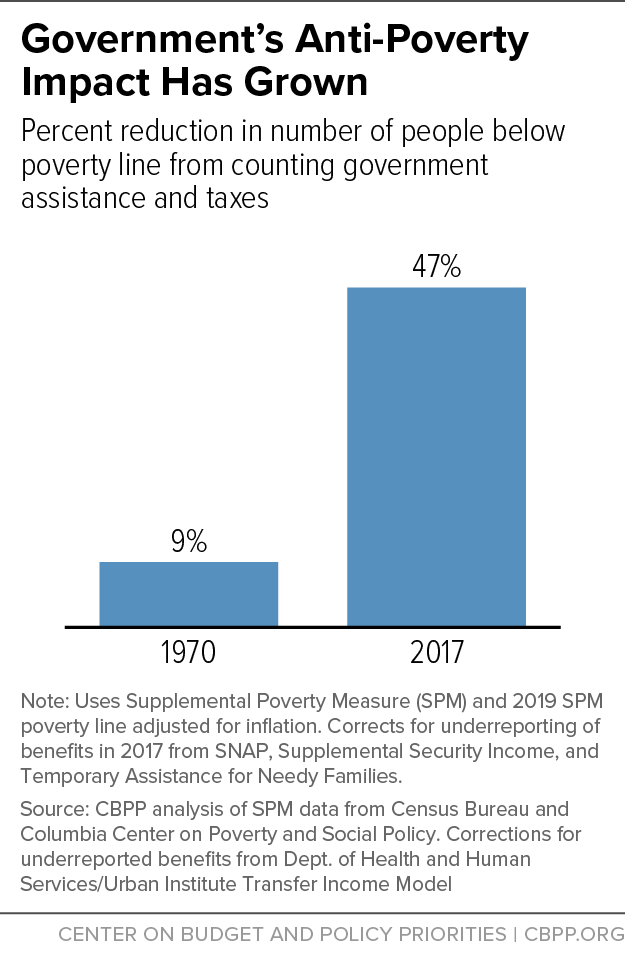

This nation’s economic and health security programs are far stronger than they were 50 years ago and do much more to reduce poverty. After accounting for the impact of government benefits and taxes, poverty fell by more than one-third between 1970 and 2017. The progress is due to policy advances. In 1970, economic security programs reduced the number of people in poverty by just 9 percent; by 2017 that figure had jumped to 47 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Government’s increasingly effective role in reducing poverty reflects the creation of programs such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for the elderly and disabled (in 1974), the national food stamp program now known as SNAP (made nationwide in 1974), tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit or EITC (in 1975) and Child Tax Credit (in 1997), as well the strengthening of older policies such as rental assistance and Social Security. Social Security lifts more people out of poverty than any other program overall, and its impact has grown as the population has aged and more people have retired. But progress in fighting child poverty has been substantial. Among children, the government role went from not reducing poverty at all in 1970 to cutting poverty by 46 percent in 2017; the tax code — because of the EITC and Child Tax Credit — lifts more children above the poverty line than any other individual program.

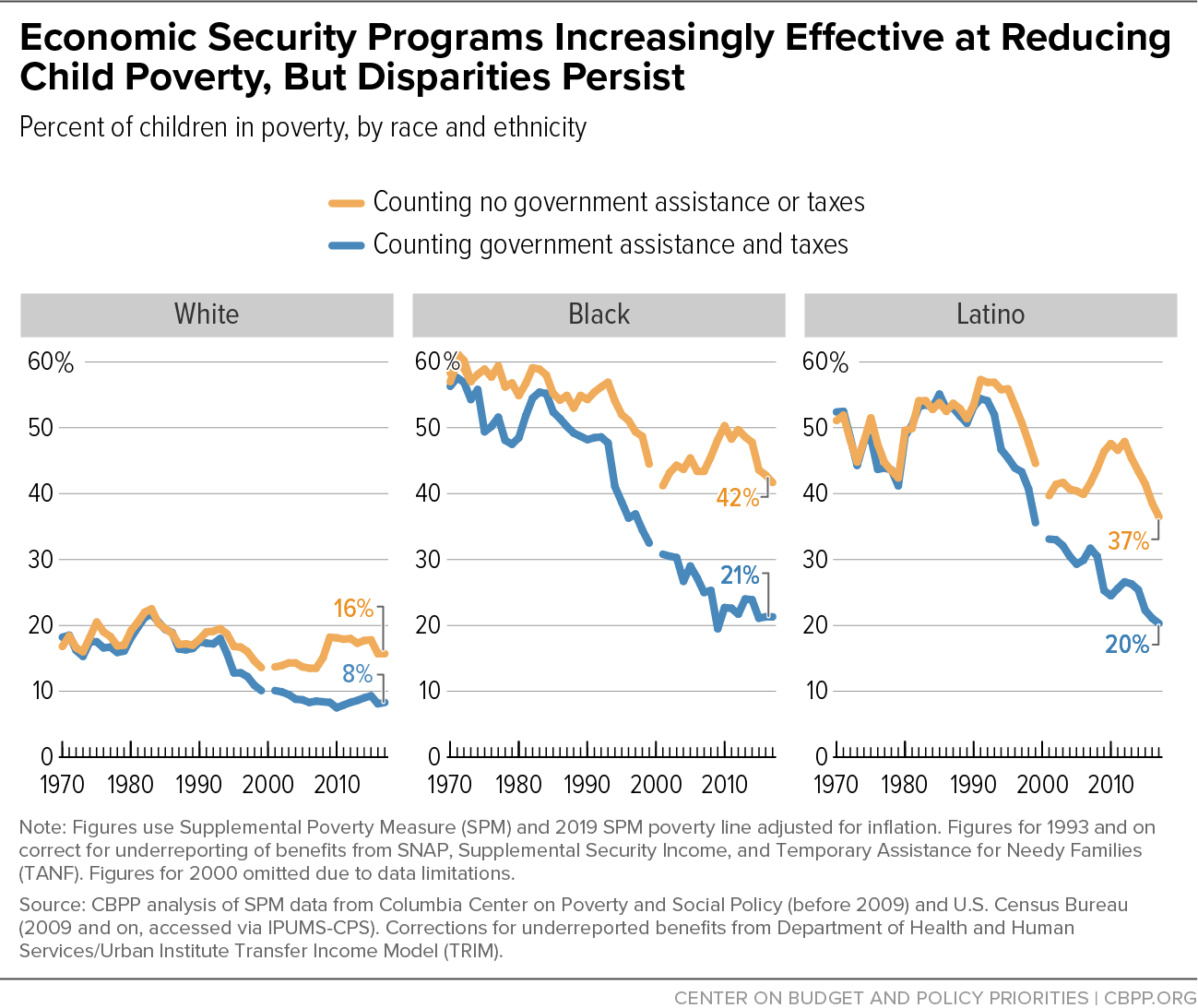

These stronger policies have reduced poverty for all racial and ethnic groups while also reducing the nation’s still-large racial differences in poverty. For example, government assistance cuts poverty by about half among Black children and among white children, but it lifts a much larger share of Black children out of poverty than of white children because poverty is more widespread among Black children.

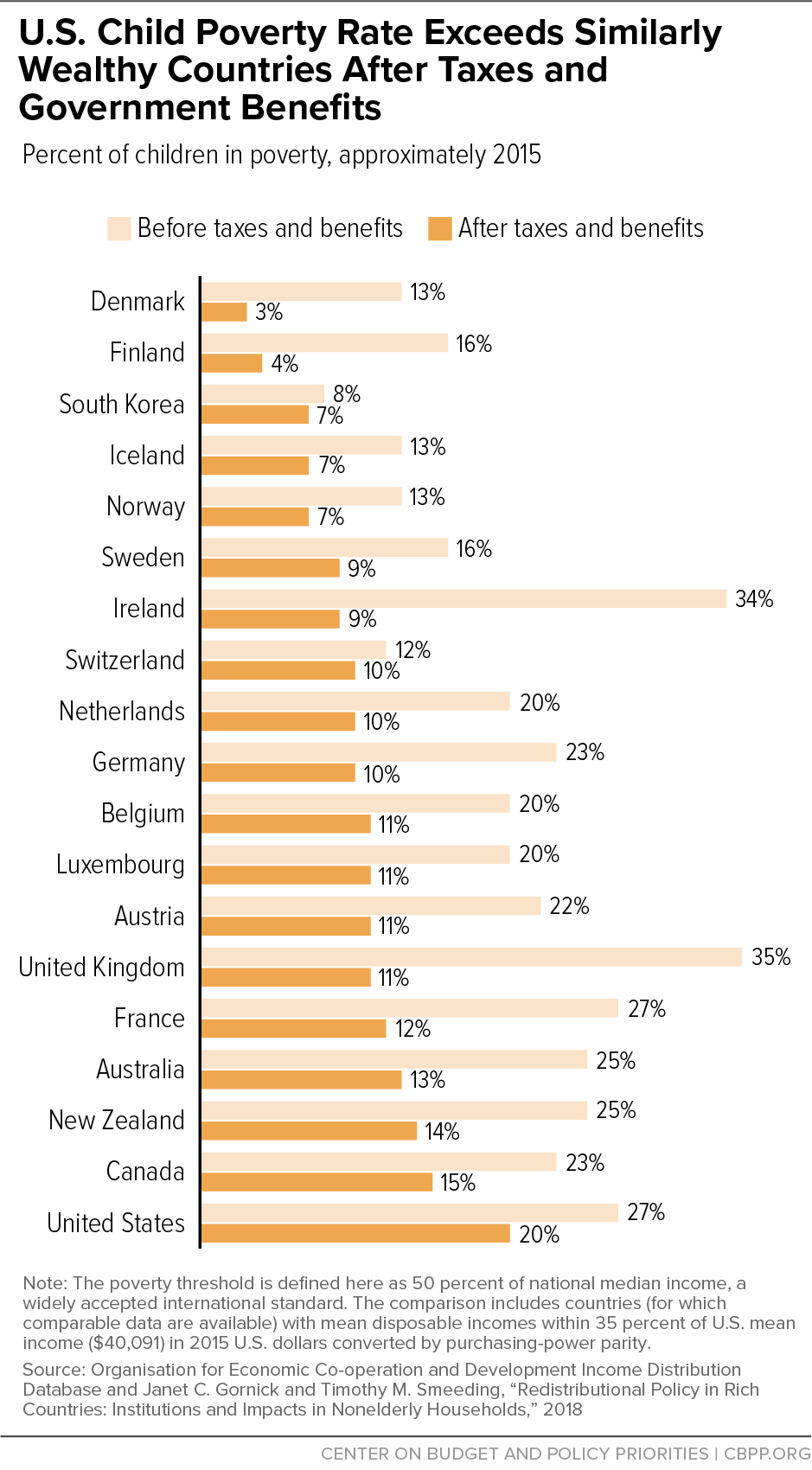

Nevertheless, U.S. anti-poverty policies have large gaps that leave U.S. children more exposed to poverty than children in other wealthy nations. For example, the U.S. has a much higher share of children living in families with incomes below half of the national median (a common way of measuring poverty internationally) than any of the world’s 18 other similarly wealthy nations. This is largely due to weaker government aid in the U.S., since many countries have child poverty rates similar to our own before counting government assistance.

In addition, an estimated 12.5 million Americans have “deep poverty” incomes, that is incomes (including government assistance) below half of the poverty line, or below just $14,200 a year for a typical family of four, after corrections for underreporting of government assistance. They include nearly 2 million children under age 18, who are particularly vulnerable to serious hardships that have long-lasting negative impacts, as well as nearly 2 million parents and other adult family members of children.

Although many families know the stresses of struggling to meet basic needs, the widespread nature of this insecurity is not always well understood, because data on such hardships seldom span more than a year of a family’s life. Many more families face hardship over multiple years than in a single year. More than 1 in 4 households, including more than 1 in 3 households with children, experienced a major form of hardship — specifically, an inability to afford adequate food, shelter, or utilities — in one or more of the years 2014, 2015, and 2016, CBPP analysis of Census data finds. Among Black and Latino households with children, roughly 1 in 2 reported one of these hardships, as did more than 1 in 4 white households with children. Even many households who are currently in the middle of the income scale may encounter hardship over time; among the middle third of households with children (ranked by their current annual income), nearly 1 in 3 reported one of these hardships over that three-year span — for example, because their incomes had fallen.

Gaps in economic security programs contribute to these problems. For example, the Child Tax Credit suffers from an “upside-down” design, providing the least help to the children who need it the most. The current design denies the credit entirely to children whose families have less than $2,500 in earnings in a single year and provides less than the full credit to low- and moderate-income families (such as a single parent with two children earning $20,000 working as a home health aide) even as married couples making up to $400,000 can receive the full credit. Some 27 million children receive a partial credit, or none at all, because their families’ incomes are too low.

Similarly, most unemployed workers do not qualify for unemployment insurance because program rules have not kept up with changes in the workforce since the system was established in the 1930s; many low-paid workers, people of color, women, and contract workers in particular, are wholly ineligible for jobless benefits when they lose their jobs. Programs like rental assistance and child care assistance help only a small share of eligible families because funding is inadequate. And the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program provides cash assistance to only a very small share of families with incomes below the poverty line, due to restrictive program rules and programmatic choices that make it hard for families to access assistance.

This nation’s long history of racism and discrimination in jobs, housing, education, and other areas also contributes significantly to poverty — and to the large differences in poverty rates among groups. As of 2017, poverty rates were more than twice as high among Black (20.9 percent) and Latino (20.1 percent) people than among white people (9.8 percent). Child poverty reflected the same dynamic, with Black and Latino child poverty rates at 21.3 and 20.3 percent, respectively, compared to 8.3 percent among white children.

Immigrants and their family members also have unique economic and health security challenges. Given the lack of progress on immigration reform, many immigrants who have been living and working in U.S. communities for decades are blocked from obtaining a lawful immigration status or accessing a pathway to citizenship and, as a result, are often subject to unfair labor practices and wage theft. Moreover, immigrants face systemic barriers to receiving help from economic security programs when they need it. Immigrants without a documented status are barred from receiving most forms of assistance; some immigrants with a documented status are also ineligible. Moreover, some immigrants or their family members are eligible for help through programs like SNAP or Medicaid but face barriers to accessing that help, including the fear that it would hurt their ability to remain in the country.

Poverty is harmful both now and over the long term. The good news is that strong research shows that reducing poverty and economic insecurity not only reduces near-term hardship but also generates lasting benefits. For example, studies have found that when programs provide additional cash assistance, participating low-income young children do better in school and earn more as adults. When elementary and middle school students received access to free school lunches, their academic performance likewise improved. When the food stamp program (now called SNAP) first expanded across the country in stages in the 1960s and 1970s, newly eligible children had better health outcomes, both as newborns and later as adults, and grew up to be more economically self-sufficient.

Another area where public investments can have both short- and long-term benefits is health coverage. Numerous studies have shown that health coverage increases access to care, improves health outcomes, and saves lives. Expanding Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), for example, prevented an estimated 19,200 deaths among near-elderly adults just in its first four years, studies found. Health insurance also improves economic security: people with health coverage are less likely to have medical debt, less likely to be evicted, and less likely to face bankruptcy, studies show.

Expansions of public programs over recent decades have greatly improved access to health coverage. Most recently, the ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility for adults and created a system of premium tax credits to help people with low and moderate incomes afford private coverage. While significant progress has been made in expanding coverage, nearly 30 million people were uninsured shortly before the pandemic. They included the 2.2 million people in the Medicaid “coverage gap;” that is, people whose incomes are too low to qualify for premium tax credits but who are ineligible for Medicaid because their states have refused to adopt the Medicaid expansion. Sixty percent of people in the coverage gap are people of color.

In response to the pandemic, policymakers approved a robust relief effort to shore up the nation’s economic security policies. Relief measures included both broad-based policies, like Economic Impact Payments, and policies that targeted those with the greatest needs, like expansions in SNAP benefits, help for those at risk of eviction, and expansions in the EITC and Child Tax Credit.

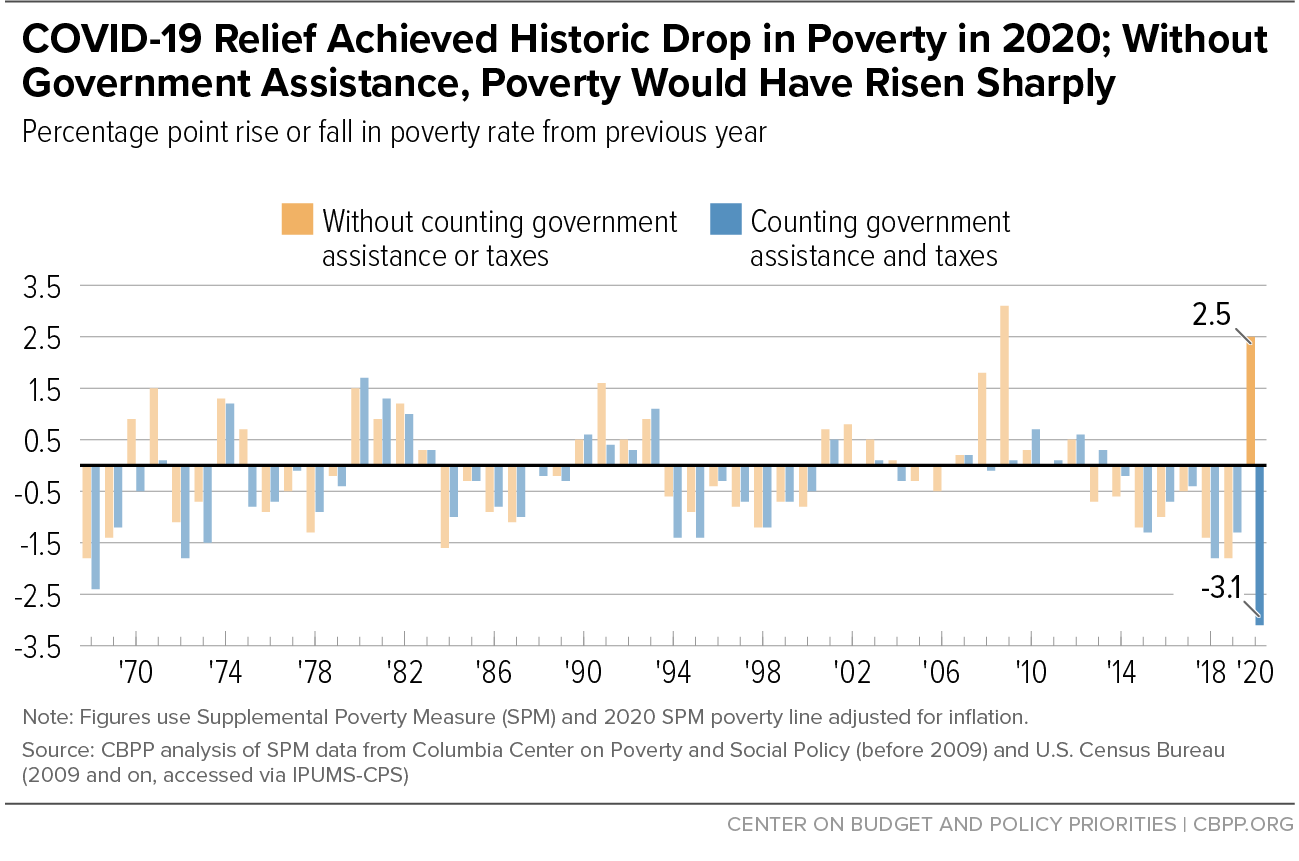

These measures largely prevented a spike in annual poverty and hardship rates and even reduced poverty significantly. The number of people in poverty fell by 10 million in 2020, the most in more than 50 years, using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) — the more comprehensive of the government’s two annual poverty measures, which counts both cash and cash-like assistance.[1] Without the COVID relief measures, the number of people with incomes below the poverty line would have risen by 8 million. The pandemic relief measures also increased access to health coverage, helped more unemployed workers weather the storm, prevented evictions, shored up the child care system, prevented many child care programs from going out of business, and ensured that state, local, territory, and tribal governments had sufficient funding to stave off deep budget cuts that could have further slowed the economy and harmed people and communities.

Some of these policies have proven effective at combatting problems that long predated the pandemic and point the way to policy advances the nation should adopt on an ongoing basis. The most notable examples are policies to better support children in low-income families: an expanded Child Tax Credit that provides the full credit to the lowest-income children, increased support for child care, and summer food benefits to prevent an increase in food insecurity when school is out.

Building on the strong research base for what is effective in reducing poverty and hardship, supporting healthy child development, and broadening opportunity, policymakers should make the investments needed to address economic and health insecurity and glaring disparities in hardship and opportunity across lines of race and ethnicity. These investments would both help families meet everyday challenges and have long-term payoffs. They would also put in place a policy infrastructure to meet the needs of families and the economy in the next recession or economic crisis. These policy advances can be financed responsibly, by raising revenues on high-income households. Such policies could include, for example:

- Helping parents make ends meet through the expanded Child Tax Credit. Policymakers should expand the Child Tax Credit and, most importantly, make the full credit available to children in families with the lowest incomes.

- Helping more households afford housing. Policymakers should make significant new investments to make housing more affordable, including expanding the number of Housing Choice Vouchers to help people with low incomes rent housing of their choice in the private market.

- Increasing health coverage and making it more affordable. Policymakers should deliver on the promise of the ACA by expanding affordable coverage to millions more people, by closing the Medicaid coverage gap and extending the expansion in premium tax credits that makes marketplace coverage more affordable.

- Improving the unemployment insurance (UI) system. Policymakers should expand the coverage, duration, and adequacy of unemployment benefits to address the shortcomings of the regular federal-state UI system.

- Strengthening pre-K and child care. Policymakers should increase the accessibility and affordability of high-quality child care and pre-K programs.

- Boosting the income of low-paid workers. Policymakers should permanently boost the EITC for working adults not raising children.

- Addressing structural barriers to supports and work for immigrants. Policymakers should address barriers to economic supports and health coverage for immigrants and their families.

- Creating a national paid leave program. Policymakers should establish a permanent paid family and medical leave program so workers can take paid time off to care for a new child, their own health issue, or a family member’s health condition while remaining connected to their jobs.

- Strengthening and better targeting TANF. Federal policymakers should reverse the long-term decline in the value of federal TANF funding. They also should set stronger national standards to guard against extremely restrictive state eligibility policies that leave many of the families with the greatest needs — including, disproportionately, Black families — with neither employment nor cash assistance

- Addressing food insecurity among children. Policymakers should strengthen proven child nutrition programs to help address a long-standing problem: many children, disproportionately those who are Black or Latino, face periods of food hardship, especially during the summer when they aren’t getting school meals.

- Improving skills and broadening access to higher education. Policymakers should invest in skill building, both through the workforce development system and by making higher education more affordable to students — for those attending right out of high school or as adults later in their careers.

Because anyone who cannot afford food, shelter, medical care, and other necessities does not have an equal opportunity to succeed in life, ensuring that all people have basic economic security is a core public duty. In the last 50 years, the U.S. has increased economic security and lowered the risk of poverty, and data from before the pandemic reveal that much of that progress is a direct result of economic security programs. Poverty remains troublingly high for all racial groups, however, and large racial inequities across lines of race and ethnicity persist in opportunity and financial insecurity.

In a recent CBPP analysis, poverty — measured comprehensively to include after-tax earnings, food and housing assistance, Social Security, tax credits, and other cash and cash-like resources — fell by more than one-third over the last five decades, from nearly 23 percent in 1970 to about 13 percent in 2017.[2] Much of this progress reflected changes in the role of government: the amount that assistance programs add to (and taxes take away from) income. How do we know? Because poverty measured in the same way but counting only private or “pre-government” income — that is, omitting government assistance and taxes — edged up slightly over this period, from about 25 percent to nearly 26 percent. (See Table 1.)

Put another way, in 1970, counting income from economic security programs reduced the number of people in poverty by just 9 percent. But by 2017, that figure had jumped to 47 percent. We are doing much more to reduce poverty than we were. If the anti-poverty effectiveness of economic security programs had remained at its 1970 level of 9 percent, over 31 million more people would have been poor in 2017, including 9 million more children.

| TABLE 1 |

| |

1970 |

2017 |

| Counting no government assistance or taxes |

25.1% |

25.6% |

| Counting government assistance and taxes |

22.7% |

13.5% |

| Effect on poverty of assistance and taxes: |

| Percentage-point reduction |

2.4 |

12.1 |

| Percent reduction |

9% |

47% |

Government’s increasingly effective role in reducing poverty reflects the creation of programs such as SSI (in 1974), the national food stamp program now known as SNAP (made nationwide in 1974), tax credits like the EITC (in 1975) and Child Tax Credit (in 1997), as well the strengthening of older policies such as rental assistance and Social Security. Social Security lifts more people out of poverty than any other program, and its impact has grown as the population has aged and more people have retired. But the improvement isn’t limited to seniors; among children, government programs did not reduce poverty at all in 1970 but cut poverty by 46 percent in 2017.[3]

Improving private incomes is important as well, of course, so that households need less help to make ends meet. The last five decades have seen progress in this area, though more is needed. Median income figures are difficult to track over long periods because household living arrangements have changed markedly, with far more small households today than 50 years ago. But median incomes for families with children have risen notably. For families with one child, for example, median income rose 28 percent between 1970 and 2017 (from $59,554 to $76,280, in 2020 dollars).[4]

Unfortunately, the share of children living in families with incomes below the poverty line when only private income is considered fell only slightly over that same period. While some societal changes — such as rising educational attainment, increased labor force participation among women, and a decline in family size — have pushed downward on poverty, other trends have pushed in the opposite direction. These include poor wage growth for many workers, widening inequality, and an increase in single-parent families who don’t receive the child support they need, often because the non-custodial parent cannot afford to pay. These forces have largely canceled each other out, leaving pre-government poverty rates high.[5]

The stronger policies that have driven down poverty overall and among children when the impact of economic security programs and taxes are taken into account have not ended differences in poverty across racial and ethnic groups. But they have shrunk those differences in percentage-point terms, while also lowering poverty for all racial and ethnic groups.

Consider poverty among Black and white children. Using income before government assistance, 16 percent of white and 42 percent of Black children were poor in 2017. Counting the role of government assistance cuts both groups’ poverty rates by about half, to 8 and 21 percent, respectively. While it is shameful that Black children are more than two and a half times likelier than white children to be poor, both before and after counting assistance, it is important also to focus on the children whose families were lifted above the poverty line by public programs. Because poverty is more widespread among Black children, cutting poverty in half means lifting a much larger share of all Black children out of poverty than of all white children.

In that sense, poverty reduction policies affect a larger share of Black children than white children. In 2017, government assistance lifted 7 percent of all white children and 20 percent of all Black children above the poverty line, reducing the Black-white difference in child poverty rates from about 26 percentage points to 13 percentage points.

Fifty years ago, government policies did little to reduce the poverty of Black children, but their growing impact since then has helped lower Black child poverty over time. Measured before counting government assistance, the Black child poverty rate declined from 58 percent in 1970 to 42 percent in 2017; after counting government assistance, it fell by more than twice as much, from 56 to 21 percent. It should be noted that at 42 percent, the pre-government poverty rate among Black children remained well above the equivalent white rate of 16 percent, reflecting continuing barriers to equal opportunity for Black families that stem from systemic racism and under-investment in Black people and communities.

The story is similar for Latino children. Government assistance (net of taxes) did not reduce Latino child poverty rates at all in 1970,[6] but by 2017, it lifted as many as 16 percent of all Latino children above the poverty line. The Latino child poverty rate after government assistance fell from 52 to 20 percent over this period.[7] (See Figure 2.)

Comparable historical figures are not available for other racial and ethnic groups, although data show that government programs lifted 236,000 Asian children (6 percent) above the poverty line in 2017.

Despite reducing poverty by half, U.S. anti-poverty policies have large gaps that leave children more exposed to poverty than other nations’ children. The gaps are harshest for some of the poorest households with the lowest earnings. These policy gaps also affect many more families over time than is widely appreciated, helping explain why, over a three-year period, even many households who are presently middle-income experience economic hardship.

Twenty percent of U.S. children live in families with incomes below half of the national median, the poverty measure most commonly used for international comparisons. This is a much higher share than in any of the world’s 18 other similarly wealthy nations, where between 3 and 15 percent of children are poor.

One key reason U.S. children are poorer is weaker government aid. Not counting the income families receive from government programs (and looking at pre-pandemic data from approximately 2015), many countries have child poverty rates similar to our own (Canada, France, Germany, and Australia, for example, have child poverty rates within four percentage points of the U.S. rate) and the British and Irish rates are well above the U.S. But all of these countries have markedly less child poverty than we do once government assistance is considered. (See Figure 3.)

The U.S. is alone among similarly wealthy nations in lacking a government-funded child allowance available to the lowest-income children.[8] Recent experience vividly shows how effective this policy tool can be against poverty. After Canada strengthened its child allowance (the Canada Child Benefit) in 2016, for example, Canada’s child poverty rate declined by one-third.[9]

In the U.S., too, expanded Child Tax Credit payments put in place by the American Rescue Plan, and available monthly without regard to family earnings for the last six months of 2021 lowered estimated monthly child poverty by nearly one-third.[10] Unfortunately, Congress allowed that expansion to expire in January 2022, ending this powerful tool for combatting poverty among children.

We estimate that in 2017, 12.5 million people lived in families with income and government assistance (net of taxes paid) below half of the poverty line, or below just $14,200 a year on average for a family of four, after corrections for underreporting of government assistance in survey data.[11] The people in “deep poverty” included 6.5 million adults aged 18-64 with no children in their family, a group that tends to qualify for the least help from economic security programs. They also included nearly 2 million children under age 18 (and 700,000 children under age 6), who are particularly vulnerable to the effects of low income, as well as nearly 2 million parents and other adult family members of children.

History shows that flawed policy choices can worsen deep poverty. Policies that take away benefits when parents cannot meet a work requirement, which are widespread in state TANF programs, contributed significantly to deep poverty in the 1990s. These policies punish families even if the parents want to work but cannot do so due to their own or their child’s health problems, or cannot find work or cannot work the required number of hours every week, or lack reliable transportation or child care — or even if their employer or the state agency doesn’t properly process the needed paperwork. While exemptions often are available on paper, they can be difficult to apply for and receive in practice, particularly for families dealing with difficult family circumstances.

In the early 1990s, in local cash assistance pilot programs that implemented this type of policy prior to TANF’s creation, deep poverty rates tended to be higher than in a randomly assigned control group, a rigorous evaluation showed.[12]

Nationwide, moreover, deep poverty among children rose in the first decade after the 1996 creation of TANF. Between 1995 (the last full year before TANF’s enactment) and 2005 (a similar point in the business cycle with a similar national unemployment rate), the deep poverty rate among children in single-mother families rose from 5.5 percent to 7.4 percent. (Deep poverty did not increase among children in married-couple families, which were not greatly affected by the 1996 law.) In 2005, an additional 300,000 children lived in deep poverty due to this increase. The increase was also largely concentrated among Black and Latino children.

The children’s deep poverty rate later receded, falling to 2.8 percent in 2017. This partly reflected policymakers’ changes in other programs (such as the Child Tax Credit) and higher participation in SNAP (in part reflecting bipartisan efforts to improve eligible families’ access to the program), which made these benefits somewhat more available to low-paid workers starting in the Great Recession. Monthly cash assistance, however, remained less available than it had been in the mid-1990s, limiting the progress against deep child poverty from those other policy changes. State spending on TANF cash assistance has dwindled as states have found more ways to reduce access to basic assistance. At the same time, unemployment benefits often exclude workers such as gig workers, people who lose work for illness or other family reasons, and part-time workers. (See further discussion below.)

All of this means that a parent who loses their job part-way through the year and can’t access TANF or unemployment benefits might have no source of cash income to cover basic expenses —rent, utilities, gas, diapers, medical needs, or new clothing for growing children — until they file their taxes the following year, when they might receive the Earned Income Tax Credit or Child Tax Credit.

Although many families know the stresses of struggling to meet basic needs, the widespread nature of this insecurity isn’t clear in official statistics because data on such hardships seldom span more than a year of a family’s life. Many more families face hardship — defined as inability to afford necessities — over multiple years than in a single year. Examining families’ economic circumstances over several years provides a fuller picture of hardship in the U.S.

CBPP analysis of Census Bureau data, newly redesigned to allow tracking of people’s hardships over multiple years, reveals how widespread economic insecurity was even before the pandemic.

More than 1 in 4 households, including more than 1 in 3 households with children, experienced a major form of hardship — specifically, an inability to afford adequate food, shelter, or utilities — in one or more of the years 2014, 2015, and 2016.[13]

Among Black and Latino households with children, roughly 1 in 2 reported one of these hardships, as did more than 1 in 4 white households with children. Even many households who are currently in the middle of the income scale may encounter hardship over time; among the middle third of households with children (ranked by their current annual income), nearly 1 in 3 reported one of these hardships over that three-year span.

High expenses for necessities like housing, child care, and medical care are a key source of financial strain. In one or more of the years from 2014 to 2016, among all households with children:

- 28 percent paid more than half of their income for housing (compared with a 14 percent one-year rate for the average of those three years). The Department of Housing and Urban Development considers housing unaffordable if it costs more than 30 percent of household income.

- 23 percent paid at least 10 percent of their income for child or dependent care (compared with an 11 percent one-year rate).[14] Experts recommend spending no more than 7 percent of income on child care, and spending more than 10 percent is considered unaffordable under current federal guidance.[15]

- 43 percent of households with children included at least one person who had no health coverage (compared with a 25 percent one-year rate), leaving households at risk of financial hardship due to medical bills and debt and likely leading some to forgo needed health care.

These expenses strain the family budgets of a larger share of Black and Latino households than white households. For example, over the three-year period, some 39 percent of Black households, 38 percent of Latino households, and 21 percent of white households paid more than half of their incomes for housing.

Other adverse consequences may follow. Families with high housing, child care, and health costs often experience hardship — that is, an inability to pay bills — in other areas as well:

- Housing. Households that must pay more than 50 percent of income for housing often have little left over for other needs and are vulnerable to foreclosure, eviction, and homelessness. In our data, households with children were twice as likely to experience food, housing, or utility hardship (that is, they were sometimes unable to pay their food or utility bills or experienced food insecurity) in a given year if they paid more than 50 percent of income for housing that year (34 percent) than if they paid less (17 percent).

- Child care. Unaffordable child care arrangements can squeeze out other necessities, restrict parents’ (typically mothers’) employment, and force children into unsafe or low quality care. In our data, households with children under age 6 that paid for child care were nearly twice as likely to experience food, housing, or utility hardship in a given year if they paid more than 10 percent of income for child care (19 percent) than if they paid less (11 percent).

- Health coverage. Lapses in health coverage leave families susceptible to catastrophic out-of-pocket medical costs. In our data, households with children were nearly twice as likely to experience food, housing, or utility hardship in a given year if someone lacked health coverage at some point that year (30 percent) than if everyone was insured (16 percent).

Gaps in our economic security programs leave individuals and families vulnerable to hardship. For example:

- The Child Tax Credit excludes those with the lowest incomes. An increasing share of economic security assistance in the U.S. comes from tax credits. Unfortunately, the design of one such credit, the $2,000-per-child Child Tax Credit is “upside down;” it shortchanges the poorest families, denying eligibility to those earning less than $2,500 in a year and providing less than the full credit to families whose earnings are above that but still low or moderate. A single mother with two children doesn’t qualify for the full Child Tax Credit until her earnings reach about $29,400. Yet the tax code provides the full credit to married filers making as much as $400,000. Some 27 million children receive a partial credit or none at all because their families’ incomes are too low, including half of Black and Latino children, 1 in 5 white children, and half of children (of any race) living in rural areas.

-

Unemployment insurance (UI) does not adequately help most workers. In the decade prior to the pandemic, the majority of jobless workers didn’t qualify for unemployment insurance benefits and those who did qualify received less than half of their previous pay, on average.[16] The share of unemployed workers receiving UI (not including the pandemic, when policymakers temporarily expanded access) has declined over many decades, reaching an all-time low of less than 30 percent prior to the pandemic. One reason is that program rules have not kept up with changes in the workforce since the system was established in the 1930s, including the increase of women in the workforce and the more recent rise of so-called gig workers. State policies often exclude workers who were in low-paying jobs, entered the labor market more recently, work part time, or lost their jobs for family or health reasons.

In the last decade, another factor driving UI coverage downward has been the deliberate effort by many states to reduce access to these benefits. Ten states now provide fewer than the traditional 26 weeks of UI benefits to qualifying workers, and three additional states have enacted cuts in UI duration starting next year.[17]

More broadly, the strength of unemployment insurance programs varies widely by state. For example, prior to the pandemic, only 1 in 10 unemployed workers received UI benefits in North Carolina but nearly 6 in 10 did in New Jersey.[18] Benefit amounts also varied greatly, from a weekly average of $213 in Mississippi to $527 in Massachusetts.[19]

-

Cash assistance for families with the lowest incomes has dwindled. In the years since policymakers replaced the nation’s main source of monthly cash aid for low-income children, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), with the more restrictive TANF program in 1996, the value of federal TANF funding has fallen 40 percent, after adjusting for inflation. States have diverted much of this diminishing funding to child care, child welfare services (such as abuse and neglect prevention), and other purposes rather than cash aid, including programs not focused on helping low-income families.[20]

States have taken advantage of the considerable freedom they have under the TANF block grant to implement policies that restrict access to the program, including upfront work requirements and policies that take benefits away from an entire family if a parent can’t meet a work requirement or if the family receives benefits for more than an arbitrary amount of time. As a result, too few families struggling to make ends meet can receive help. If TANF had the same reach in 2020 as AFDC did in 1996, 2.38 million more families nationwide would have received cash assistance. Instead, in 2020, for every 100 families in poverty nationwide, only 21 received TANF cash assistance — down from 68 families in 1996.[21]

Recent research has shown that states where Black residents make up larger shares of the population spend less TANF funding on basic assistance, have lower monthly benefit levels, and have more punitive policies that take families’ benefits away for not meeting work requirements. In fact, 52 percent of Black children in the U.S. live in states with benefit levels below 20 percent of the poverty line, compared to 41 percent of Latino children and 37 percent of white children.

- Child care and rental assistance work well for families who receive it, but most families eligible for help paying for child care and rent don’t get it because funding is inadequate. Only about 1 in 4 households eligible for rental assistance receive it, because funding — which is set annually through the appropriations process — falls far short of what is needed.[22] Similarly, prior to the pandemic, only about 1 in 7 children whose families were eligible for child care assistance received it.[23] Child care’s steep price tag — the average cost of center-based care for a toddler exceeded $10,000 in a majority of states in 2020 — puts it out of reach for workers who are paid low wages if they don’t receive assistance.[24]

Racism and Bias Contribute to Large Racial and Ethnic Differences in Poverty

Our success as a nation ultimately depends on whether all families, regardless of race or ethnicity, have the opportunity to thrive. But a long and continuing history of racism and bias has erected racial barriers to success, restricting opportunities for people of color in jobs, housing, education, and other areas and fueling racial and ethnic differences in economic security.

Job discrimination, for example, remains common. Mock resumes submitted with stereotypically white-sounding names were between 24 and 29 percent more likely to receive a callback than equivalent resumes with Black-sounding names and 25 to 31 percent more likely than Hispanic-sounding names, according to an overview of dozens of recent studies.[25]

Housing discrimination and insufficient enforcement of fair housing rules create further barriers. When real estate agents responded to renters’ inquiries about recently advertised housing, they gave Black renters information on 11.4 percent fewer available units than equally qualified white renters and showed them 4.2 percent fewer units, one study found. Similarly, agents gave Hispanic renters information on 12.5 percent fewer units (compared to white renters) and showed them 7.5 percent fewer, and gave Asian renters information on 9.8 percent fewer units and showed them 6.6 percent fewer.[26]

While many public economic security policies advance racial equity, other government policies and practices undermine it. For example:

- State tax rules dating from periods when discrimination and racism were more overt than today contribute to the underfunding of schools and other public services. For example, many state constitutions require a legislative supermajority vote of 60 percent or more to raise revenue, which makes it difficult to adequately fund schools and other services that promote equal opportunity. The oldest such supermajority requirement still on the books in any state dates from 1890 in Mississippi. Delegates there adopted the measure at the same state constitutional convention at which they disenfranchised nearly all of the state’s Black voters. Referring to his fellow convention delegates, the delegate who introduced the supermajority requirement stated, “All understood and desired that some scheme would be evolved which would effectually remove from the sphere of politics in the State the ignorant and unpatriotic negro.”[27]

- Research consistently shows that Black families are more likely than white families to have their TANF benefits taken away — that is, to be sanctioned — for inability to demonstrate compliance with a work requirement.[28] Researchers who presented TANF case workers with fictitious case examples in order to study racial bias found that, all else being equal, caseworkers were significantly more likely to say they would take benefits away from a Black mother with previous sanctions (94 percent) than an otherwise identical white mother with previous sanctions (77 percent).[29]

Decades of past racial discrimination also take a toll on parents’ wealth, education, job networks, and other resources, which in turn affects their children’s economic security and educational opportunities. Today’s Black and Latino parents, for example, grew up in decades that featured even higher poverty rates and lower incomes than today. Similarly, today’s higher poverty and economic insecurity rates among Black and Latino children, which research tells us shortchanges their futures, will have follow-on consequences for their economic security as adults (and the economic security of their children).

Past and present discrimination in both private markets and public policies left poverty rates in 2017 more than twice as high among Black (20.9 percent) and Latino (20.1 percent) people than among white people (9.8 percent). Child poverty reflected the same dynamic, with Black and Latino child poverty rates at 21.3 and 20.3 percent, respectively, compared to 8.3 percent among white children.

Poverty is harmful both in the near term and over the long term. The good news is that strong research shows that reducing poverty and economic insecurity not only reduces near-term hardship but improves long-term outcomes.

Studies link additional income with better outcomes for children in families with low incomes, including better educational performance and attainment, higher earnings in adulthood, and better health, which can yield benefits for children and their communities over the course of their lives.[30]

Studies have found, for example, that:[31]

- When children grew up in a household receiving additional cash benefits, their academic achievement increased.

- When elementary and middle school students received access to free school lunches, their academic performance improved.

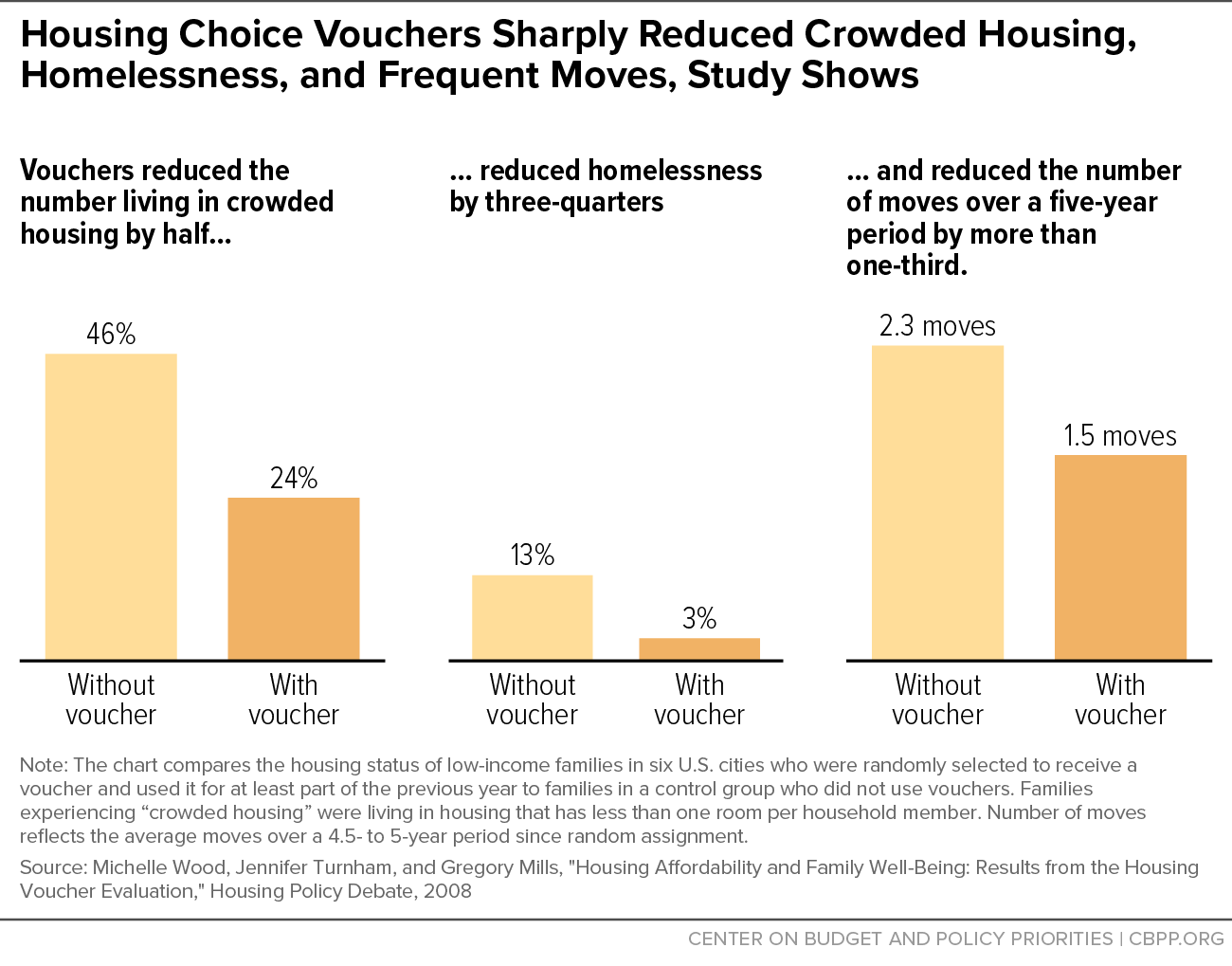

- When families with low incomes received rental assistance, they were less likely than unassisted families to experience homelessness, housing instability, or overcrowding — problems linked to far-reaching harmful effects on families and children.

- Assistance paying for quality child care can help families make ends meet and increase parental employment rates while also improving children’s behavioral and academic outcomes.

- When children had access to quality pre-kindergarten at age 4, they were likelier to enter college on time.

- When high school students were guaranteed grants to pay for community college, they were likelier to complete community college.

- When low-income college students received additional grants, they were likelier to persist in and complete college — even more so when grant aid was combined with additional supports.

- When parents had access to paid family leave, rates of early births and low birthweights declined, especially for Black mothers, whose incidence of these problems started higher.

- When mothers received more cash assistance in a recent randomized trial, results suggested promising changes in babies’ brain development.[32]

A Consensus Study Report from the National Academy of Sciences underscored the difference that anti-poverty programs can make for children: “Many programs that alleviate poverty either directly, by providing income transfers, or indirectly, by providing food, housing, or medical care, have been shown to improve child well-being.”[33]

Poverty and hardship take a toll on adults as well as children. Simply raising monetary concerns for people with low income can erode their cognitive performance even more than serious sleep deprivation, one study showed.[34] Another study found that low-income mothers given larger tax credits showed signs of reduced stress, such as less inflammation and lower diastolic blood pressure.[35]

Numerous studies have shown that health insurance coverage increases access to care, improves health outcomes, and saves lives.[36] Expanding Medicaid coverage under the ACA, for example, increased the receipt of health care ranging from cancer diagnosis to smoking cessation treatment, and it lowered infant mortality, opioid deaths, and cardiovascular mortality for middle-aged adults. And, in its first four years, Medicaid expansion prevented an estimated 19,200 deaths among near-elderly adults, studies found. Expansion also lowered maternal mortality, particularly the elevated mortality rates of Black mothers.[37]

Health insurance is also fundamental to economic security. It lowers medical debt (the most common form of debt, held by 100 million people in the U.S.)[38] and the risk of facing catastrophic out-of-pocket medical costs.[39] It also reduces evictions and bankruptcies and improves credit scores.[40] Medicaid in childhood has been found to improve school performance, and, as the children reach adulthood, to reduce their risk of disability and increase their labor supply.[41]

Expansions of public programs over recent decades have greatly improved access to health coverage. Medicaid, created in 1965, has been expanded multiple times: in 1989 to include children under age 6 in families with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, for example, and in 1990 to cover children up to age 18 under 100 percent of the federal poverty level. In 1997, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was signed into law to provide coverage for children whose family incomes were low but not low enough to qualify for Medicaid. CHIP provided incentives for states to further increase eligibility for children, and nearly every state now provides coverage for children up to at least 200 percent of poverty. [42] And, some states used their new flexibility starting in 1996 to expand coverage for parents with low incomes who were not receiving cash assistance.

This progress, however, was largely limited to children, pregnant or postpartum adults, and in some states, parents. A significant expansion for adults did not come until the ACA passed in 2010. It expanded Medicaid eligibility for adults up to 138 percent of poverty for states that chose to expand. The ACA also created a system of premium tax credits that allows people with low and moderate incomes to purchase subsidized private coverage through the ACA marketplaces.

The Medicaid expansion was intended as a mandate but a Supreme Court decision made it a state option, and 12 states (many of them in the South) have refused to adopt it. As a result, some 2.2 million people with incomes below the poverty level — 60 percent of whom are people of color — fall into the Medicaid coverage gap. [43] That is, their incomes are too low for them to qualify for tax credits to purchase coverage in the ACA marketplace, but they are ineligible for Medicaid because their states have refused to adopt the expansion.[44]

Some 71 million people[45] were enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP as of February 2020,[46] prior to the pandemic, and about 14.5 million people signed up for coverage through the ACA marketplaces during the 2022 open enrollment period.[47] The overwhelming majority of people with marketplace coverage receive premium tax credits to defray some of the cost.[48]

While significant progress in expanding health coverage has been made, nearly 30 million people were uninsured shortly before the pandemic, including the 2.2 million in the Medicaid coverage gap.[49] Latino and Black people are more likely to be uninsured than other groups; prior to the pandemic, their uninsured rates were 18.7 percent and 10.1 percent, respectively, compared to 6.3 percent for white, non-Latino people.

The COVID relief effort was robust and featured a number of successful policy innovations. As a result, the nation achieved historic gains against poverty and lowered hardship despite the twin economic and health crisis caused by the pandemic.

Relief measures included both broad-based policies, like Economic Impact Payments, and policies that targeted those with the greatest needs, like expanding access to unemployment benefits and increasing benefit levels, expanding SNAP benefits and getting food assistance to children missing out on school meals, helping those at risk of eviction, and expanding the EITC and Child Tax Credit. (While the child credit expansion was broad based, it also made the full credit available to the lowest-income children for the first time.) Policymakers also increased access to health coverage during the pandemic by helping more people stay connected to Medicaid and making marketplace coverage more affordable. Measures targeting those facing the greatest need were critical in preventing spikes in poverty, hardship, and lack of health coverage; they also promoted equity amidst a pandemic and economic crisis that hit Black, Indigenous, and Latino people particularly hard.

Such bold action was necessary, in large part, because of the underlying gaps in our economic and health security programs. If, for example, our unemployment insurance system was more robust, covering more workers who lose their jobs and providing more adequate benefits, some of the emergency measures wouldn’t have been needed, states wouldn’t have scrambled to implement those measures while handling a spike in applications, and delays in providing needed aid would have been less severe.

But since robust measures were taken, we learned quite a bit about the effectiveness of some of these policies at combatting problems that long predated the pandemic and point the way to policy advances the nation should adopt on an ongoing basis. These include policies that:

- Support children in families with low incomes, including an expanded Child Tax Credit that provides the full credit to children in the lowest-income families, increased support for child care, and summer food benefits to prevent an increase in food insecurity when school is out;

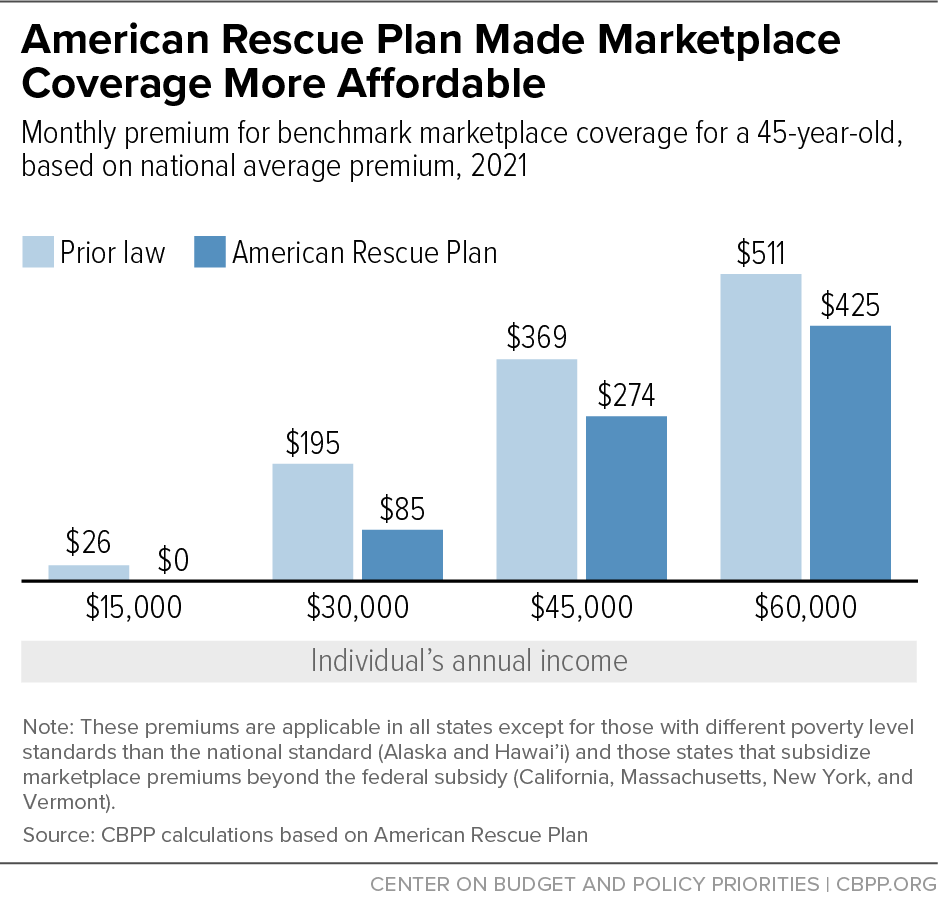

- Boost health coverage, including expanded premium tax credits to make marketplace coverage more affordable and increased continuity of Medicaid coverage (though very low-income people in non-expansion states continued to go without coverage during the pandemic because steps were not taken to close the coverage gap);

- Support workers, including an expanded EITC for workers without children and a revamped unemployment insurance system that protects workers when they lose their jobs and ensures that a temporary job loss does not create a financial crisis for workers and their families; and

- Help low-income households afford housing and avert eviction, such as expanded housing vouchers and eviction prevention assistance.

The federal response was not perfect. Many individuals and families experienced long delays before obtaining benefits, services, and supports. Policymakers allowed aid to stall in the latter part of 2020, leading to unnecessary hardship that swifter action could have avoided. But overall, the effort was highly effective at mitigating harm during an enormously difficult chapter in the nation’s history.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of federal relief policies in preventing greater hardship during the pandemic. The pandemic’s sharp earnings declines could have triggered suffering unprecedented in the post-World War II era, as well as a more protracted downturn and longer period of high unemployment. While many families had harsh financial ups and downs due to the severity of the crisis and delays and gaps in assistance, relief measures lifted many households’ incomes above pre-pandemic levels for 2020 as a whole, turning a likely near-record spike in poverty into a remarkable overall decline in poverty in annual Census figures.

The number of people with annual income below the poverty line in 2020 fell by 10 million from the year before, using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which counts both cash and cash-like assistance in determining poverty status. This one-year decline was the largest in more than 50 years and brought this measure of poverty to its lowest point on record, in data back to 1967.[50] Without the government assistance provided through COVID relief measures, the number of people in poverty would have risen in 2020 by 8 million, the second-largest amount on record.[51] Government assistance lifted 53 million people above the poverty line in 2020, well above the previous record of 40 million people in 2009. (The decline in the poverty rate was also the largest in more than 50 years. See Figure 4.)

While final annual poverty figures for 2021 are not yet available, it is clear that relief measures — including those enacted in 2020 and those in the American Rescue Plan — had a sizable impact on poverty in 2021; poverty would have been markedly higher without them. According to multiple projections, poverty in 2021 is likely to remain well below any pre-pandemic level on record, with data back more than 50 years.

Indeed, a number of preliminary projections suggest that the American Rescue Plan could prove to be the single most effective piece of legislation since the 1935 Social Security Act for reducing poverty and economic hardship in a given year. (The 2020 CARES Act may come close, and the combination of CARES and the other relief measures enacted in 2020 may well have jointly reduced poverty by more than the Rescue Plan alone.)

Columbia University researchers estimate that the Rescue Plan’s advance Child Tax Credit payments reduced the number of children in monthly poverty in December 2021 by 3.7 million. (When the payments expired the following month, child poverty snapped back upward by over 40 percent.) The Rescue Plan overall, including the Child Tax Credit expansion as well as other major provisions such as $1,400-per-person Economic Impact Payments, SNAP benefits, expanded unemployment benefits, a larger EITC for workers without children, and a Child and Dependent Tax Credit expansion, is projected to have reduced annual poverty in 2021 by more than 12 million people when compared with poverty without this aid. That includes 5.6 million children kept out of poverty by the Rescue Plan, a reduction in child poverty of 56 percent.[52]

Indications of the potency of the policy response in reducing hardship include the following:

- Major measures of food hardship held steady, despite record job losses. The rate of food insecurity in 2020 (the latest year for which the Department of Agriculture has detailed annual data) was statistically unchanged from 2019. Less detailed weekly data from the Census Bureau showed the number of adults reporting that their household didn’t get enough to eat in the last seven days fell sharply in 2021 after each of a number of infusions of relief payments, including the Economic Impact Payments and monthly Child Tax Credit benefits provided by the American Rescue Plan.[53]

- Medicaid enrollment increased by over 16 million from February 2020 to February 2022 due to relief provisions that provided continuity of coverage, and ACA marketplace enrollment grew by more than 3 million from 2020 to 2022. Without these measures, the number of people without health coverage during a pandemic almost certainly would have risen.

- Despite significant administrative challenges, millions of people received jobless benefits because of temporary eligibility expansions and tens of millions received increased benefits. Jobless benefits kept 5.5 million people out of poverty in 2020, Census data show. The Urban Institute projected during 2021 that unemployment benefits overall would keep 6.7 million people above the poverty line that year and that the Rescue Plan’s expansion of these benefits alone would lower poverty from 13.7 to 12.6 percent, or by more than 3 million people.[54]

- There was no surge in evictions in 2021 when the national eviction moratorium was lifted even though millions of people were behind on rent. This was due to relief measures overall that helped households make ends meet and brought back jobs more quickly as well as to critical housing-specific measures. More than 5.7 million households received emergency rental assistance from January 2021 through April 2022 to help them with past-due and current rent bills, forestalling eviction for many.

The economic fallout from the pandemic was especially severe for workers in low-paid sectors of the economy, such as restaurants and hospitality, in which people of color and women are overrepresented. Black and Latino people entered the pandemic with lower incomes and fewer assets due to structural racism and discrimination, which have limited opportunities for people of color in employment, housing, education, and other areas. This meant that many elements of the pandemic response that targeted those with the greatest need had particularly large, positive impacts on Black and Latino people.

At the same time, many relief measures excluded some immigrants, who are important members of our communities and who were particularly affected by the pandemic and recession, and immigrants and their families often feared receiving help they qualified for. The American Rescue Plan helped by expanding access to Economic Impact Payments — providing them to people with Social Security numbers who lived with others without an SSN — and the Biden Administration has taken steps to reduce fear among immigrants and their families so that they don’t forgo help they need and qualify for.

Surveying the relief policies’ impacts on hardship, H. Luke Shaefer of the University of Michigan concluded: “While we should always think about the ways that we can do better, I think it is also critical to recognize the successes we have had. This is the best, most successful response to an economic crisis that we have ever mounted, and it is not even close.[55] (Emphasis added.)

Pandemic Relief, Other Evidence Provide Lessons for Policymakers

The COVID relief effort teaches that well-designed relief measures can reduce the harm done by a recession or crisis, largely avoiding widespread hardship. The measures we put in place in 2020 and 2021 largely prevented a spike in annual poverty and hardship rates and even reduced poverty significantly as compared to pre-pandemic levels, increased access to health coverage, helped more unemployed workers weather the storm, prevented evictions, shored up the child care system, prevented many child care programs from going out of business, and enabled state, local, territory, and tribal governments to stave off deep budget cuts that could have further slowed the economy and harmed people and communities.

Economic and health security programs have an important role to play even when the economy is healthy, by supporting individuals and families who nonetheless fall on hard times due to job loss or other factors. Many people are paid low wages that aren’t enough to make ends meet. And personal circumstances such as a worker’s illness or a family member’s need for care can lead families to need help. Finally, in a dynamic economy, resources are constantly reallocated to their most effective use. This means that even in times of economic growth, some businesses are closing and jobs are being lost.

Shoring up our permanent economic and health security policies would not only improve well-being and reduce poverty in the short term but also, as discussed above, expand opportunity and promote well-being over the long term. Multiple studies demonstrate lasting benefits from a wide array of programs, both those counted as income in the SPM (such as cash assistance, nutrition and rental assistance, child nutrition, and tuition assistance) and policies such as quality child care, preschool, and paid parental leave that can lift families’ earnings.

Strengthening economic and health security policies can also strengthen the nation’s resiliency to recessions and other crises. Currently, our “automatic stabilizers” — the features of tax laws and spending programs like unemployment insurance and SNAP that automatically reduce income losses and support consumer spending in a downturn — are weaker than in other countries. This requires policymakers to enact larger temporary discretionary measures to mitigate the effects of a downturn, as during the pandemic. If we had a stronger set of economic and health security policies that automatically helped more people when they fall on hard times, fewer discretionary measures would be necessary during a recession, mitigating the risk that policymakers may not act quickly enough or do enough to assist those in need.

Building on the experiences of the last two recessions and the strong research base for a number of policies, policymakers should make the investments needed to address economic and health insecurity and glaring disparities in hardship and opportunity across lines of race and ethnicity. These investments would both help families meet everyday challenges and have long-term payoffs. They would also put in place a policy infrastructure to meet the needs of families and the economy in the next recession or economic crisis.

Today’s uncomfortably high inflation is no excuse to further delay action against long-standing policy shortcomings that, despite progress, still result in high levels of poverty, lack of affordable health coverage for many, and highly unequal access to opportunity. The nation can afford policy advances that address these issues and can finance them responsibly.[56] Nor is inflation an excuse for inaction on solvable problems that shortchange the lives and futures of millions of people and diminish the nation.

Failure to address these serious issues would have long-term negative consequences. When children don’t have economic security — when their families struggle to afford the basics — they are less likely to grow up healthy and succeed in school. Not only does this shortchange their futures, but lack of investing in our children robs the nation as a whole of benefitting from their full potential. A near-term inflation problem is no reason to underinvest in proven strategies that help children thrive.

Some examples of policies that should be enacted are described below.

Policymakers should expand the Child Tax Credit and, most importantly, make it “fully refundable,” meaning that children in families with the lowest incomes would receive the same amount as children in higher-income families, and should deliver payments on a monthly basis. Simply making the current $2,000-per-child credit fully refundable (apart from other benefit expansions) would reduce child poverty in 2022 by about 17 percent, lifting an estimated 1.7 million children above the poverty line.

In addition to making the credit fully refundable, the American Rescue Plan’s one-year expansion of the Child Tax Credit increased the maximum credit amount (to $3,600 for children under age 6 and $3,000 for children aged 6 to 17), allowed families to claim their 17-year-old children for the first time, and delivered half of the credit via advance monthly payments rather than entirely as a lump sum at tax time.[57] These payments — which were delivered to over 61 million children in December 2021[58] — sharply reduced monthly child poverty and reported food insufficiency, with full refundability almost certainly being the main driver of that poverty reduction. There is no evidence the payments negatively affected parental employment.[59]

The Rescue Plan’s improvements in the Child Tax Credit also reached all five U.S. Territories — Puerto Rico, Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands — which together are home to nearly 4 million U.S. residents. Not only did the Rescue Plan extend its temporary expansions of the credit to the territories, it also permanently erased long-standing discriminatory barriers that had prevented the bulk of families with children in the territories from accessing the credit. Further improvements to the credit would significantly reduce child poverty in the territories, which is much higher than in the rest of the country.

Policymakers should make significant new investments to make housing more affordable, including expanding the number of Housing Choice Vouchers to help people with low incomes rent housing of their choice in the private market. As noted, vouchers and other rental assistance only reach 1 in 4 eligible low-income households due to inadequate funding, and there are long waiting lists for assistance around the country.[60]

Studies show that vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. (See Figure 5.) And because stable housing is crucial to many aspects of a family’s life, vouchers have numerous other benefits. Children in families with vouchers are less likely to be placed in foster care, switch schools less frequently, have fewer behavioral problems, and are likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors such as offering to help others. Vouchers also give families greater choice about where they live; when families use vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, their children are more likely to attend college and earn more on average as adults.[61] And vouchers provide stable housing for people experiencing homelessness and support seniors and people with disabilities, many of whom face serious housing affordability and access challenges.

The economic fallout from the pandemic caused millions of households to fall behind on rent, putting them at risk of eviction and homelessness, adding to the crisis of homelessness and housing instability that already existed when the pandemic hit. Policymakers took unprecedented measures to keep renters in their homes during the pandemic, including an eviction moratorium put in place by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[62] To help renters with past-due and current rent bills, policymakers also allocated $47 billion of emergency rental assistance. Over 5.7 million households received this assistance between January 2021 and April 2022, which likely played a key role in preventing a surge in evictions after the end of the national eviction moratorium in August 2021.[63] Nationally, the emergency rental assistance program is on pace to exhaust nearly all of its funding by late 2022;[64] this adds to the urgency of addressing the underlying housing instability that made millions of renters vulnerable to losing their homes during the pandemic. Expanding ongoing rental assistance programs to meet significant unmet need is a critical first step, starting with a major expansion of vouchers.

Increasing Health Coverage and Making It More Affordable

Policymakers should deliver on the promise of the ACA by expanding health insurance to millions of uninsured people and improving affordability for millions more. These steps would take further strides toward universal coverage and reduce racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in coverage.[65]

The ACA cut the nation’s uninsured rate nearly in half, but nearly 30 million people — including millions of working people, parents, people with disabilities, and others — remained uninsured prior to the pandemic. People with low incomes are more likely to be uninsured than those with higher incomes. People of color make up a majority of the uninsured because they face structural barriers such as income and wealth inequities and are disproportionately likely to work in lower-paid jobs, which often don’t come with health benefits.[66]

More than 2 million uninsured people with incomes below the poverty line are in the Medicaid coverage gap because they live in one of 12 states that have failed to adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. People in the coverage gap are adults of varying age, race, and ethnicity; in 2019 some 60 percent were people of color, reflecting long-standing racial and ethnic discrimination.[67] An estimated 445,000 people in rural areas fall into the coverage gap; in fact, the rural uninsured rate in 2019 was nearly twice as high in non-expansion states as in expansion states (21.5 vs. 11.8 percent).[68]

Policymakers should close the coverage gap. They also should extend the Rescue Plan’s premium tax credit improvements, which eliminate or reduce premiums for millions of marketplace enrollees, ensuring that people spend no more than 8.5 percent of their income on premiums and that people with low incomes pay far less. (See Figure 6.) These improvements have already boosted marketplace enrollment.

Improving Unemployment Insurance Benefits and Administration

Policymakers should expand the coverage, duration, and adequacy of unemployment benefits to address the shortcomings of the regular federal-state UI system. Under the regular system, significant gaps in UI coverage exist for workers in low-paid, part-time, or intermittent work, while self-employed contractors, including gig workers, and new labor market entrants are completely shut out. These large holes in UI coverage and benefits disproportionately hurt workers of color.

Equitable coverage and adequate benefits should be a paramount goal for UI. That’s important not just during recessions but also during normal economic times, when millions of workers still lose their jobs through no fault of their own and need assistance as they look for new ones. Federal policymakers ultimately need to enact legislation to comprehensively reform the UI system on a permanent basis.

The pandemic highlighted both the importance of benefit expansions for reducing hardship and the weaknesses of state UI systems for delivering these benefits. Despite the strenuous efforts of many officials to simultaneously address a massive surge in UI claims while quickly starting up new programs, the state-administered UI system was ill prepared to cope with the enormous wave of unemployment of early 2020. Inadequate staffing, outdated technology, and confusion about new eligibility criteria all likely hindered the system’s response. The results were significant delays in processing benefits and higher vulnerability to fraud.

Those difficulties demonstrate the need to modernize and strengthen UI administrative systems. However, efforts to reduce fraud must not erect new barriers to benefits for eligible workers. Increased customer service will likely be needed to help the most vulnerable individuals comply with any new requirements, particularly those related to identity verification. Ultimately, the experience of temporary unemployment programs during the pandemic makes a strong case for permanent federal UI reforms so that states are not forced to rapidly implement major program changes while responding to a deluge of new claims during a recession.

Finally, without federal reform, a weak UI system will become even weaker. After the Great Recession, ten states restricted access to regular unemployment benefits by slashing their duration. In 2022, three more states (Iowa, Kentucky, and Oklahoma) have cut their UI benefit duration significantly, and other states have considered similar reductions. These cuts fall particularly hard on workers of color, since their average duration of unemployment is longer than for white workers.

Strengthening Pre-K and Child Care

Policymakers should increase the accessibility and affordability of high-quality pre-K and child care programs. State-funded pre-K programs enrolled only 34 percent of 4-year-olds and 6 percent of 3-year-olds in 2019-2020.[69] In addition, only 1 in 7 eligible children receive federal child care assistance due to lack of funding.[70] Black children have the least access to high-quality child care, and Black and Latino children face the greatest child care affordability challenges.

Robust research demonstrates the positive long-term results from effective early childhood programs. Randomized control trials of small pre-K programs that tracked children over decades show robust effects on high school graduation rates, college enrollment, and adult earnings.[71] Notable research on programs operating at scale, including Head Start and Boston’s citywide pre-school initiative, has also shown lasting gains for children.[72] Although findings are not uniform,[73] a preponderance of evidence suggests lasting gains for children from quality pre-K programs.[74]

High-quality child care can also yield lasting benefits for families. Increasing the accessibility and affordability of child care has been shown to boost maternal employment.[75] Parents who don’t have access to affordable child care but nevertheless need to work often must rely on lower-quality, unstable child care arrangements that have negative impacts on children’s development and can lead to lost work hours and increased family stress.[76] Several studies document positive long-term educational and developmental impacts of high-quality child care, especially for disadvantaged children. A 20-year longitudinal study, for example, found that attending high-quality child care was consistently associated with higher performance on standardized tests and higher grades.[77]

Quality and design are critical in the context of early childhood programs.[78] To ensure high-quality programs requires, for instance, setting high standards for curriculum and child development; providing adequate pay, training, and opportunities for advancement for staff (who, particularly in the context of child care, are often badly underpaid, resulting in high turnover); using data for quality improvement; and encouraging strong family engagement.

Policymakers should permanently boost the EITC for working adults not raising children. The Rescue Plan temporarily raised both the maximum credit for these workers (from roughly $540 to roughly $1,500) and the income cap for them to qualify (from about $16,000 to at least $22,000). It also temporarily expanded the age range of eligible workers without children to include younger adults aged 19-24 (excluding students under 24 who are attending school at least part time), as well as people aged 65 and over.

This one-year expansion increased the incomes of more than 17 million working adults without children who do important work for low pay. They include nearly 5.8 million people aged 19 to 65 whom the federal tax code would otherwise tax into, or deeper into, poverty — the lone group for whom that happens — in large part because their EITC would otherwise be too low.

Policymakers should address barriers to economic supports and health coverage for immigrants and their families. For example, they should eliminate the so-called “five-year bar” policy, which blocks many immigrants who have lawful immigration statuses from accessing most federal means-tested programs, including TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid.

The Biden Administration has proposed new “public charge” rules to help address fears that have deterred immigrants and their families from receiving benefits for which they are eligible. To maximize the benefit of these policy improvements, Congress should authorize funding focused on outreach aimed at addressing those fears.

In addition, many immigrants have lived in our nation for most of their lives and have contributed to our communities in many ways yet have no pathway to a lawful immigration status or citizenship. These individuals face barriers to employment and are vulnerable to wage theft and other unfair employment practices. Congress should adopt comprehensive immigration reform to address this crisis.

Policymakers should establish a permanent paid family and medical leave program. The United States is alone among wealthy countries in lacking a national paid leave program; instead, we have a patchwork of federal, state, and local policies. Federal law affords a little over half of workers access to unpaid leave but provides no national paid leave. Eleven states and the District of Columbia have paid leave programs at various stages of implementation, but most workers don’t live in those states. And while some employers voluntarily offer paid family and medical leave, the vast majority do not.

Paid leave offers improved economic security for families by making it possible for working people to meet family obligations and stay healthy while keeping their job and receiving a paycheck. In the absence of such paid leave, a worker with a new child or a sick family member, or a worker who becomes sick, often faces only bad choices. They can take unpaid leave and sacrifice income that may be critical for their family’s well-being. Or they can stay at work, forgo providing or being provided care, and risk losing their job anyway due to emergencies or strain.[79] One in five low-paid working mothers report losing a job because of illness or the need to care for a family member.[80] Paid leave also benefits businesses by improving retention and productivity and boosting labor force participation.

A national paid leave program should cover comprehensive reasons for leave, including caring for a new child and for a worker’s serious health condition or that of a family member. It should be generous enough that low- and middle-income workers can meet their families’ needs while on leave. Overall, policy design should ensure that paid leave is fully accessible to all workers. It also should prioritize the needs of low-paid workers, workers of color, and other marginalized groups who are disproportionately ineligible for current leave policies and face more barriers to accessing benefits even when they are eligible.

Strengthening and Better Targeting TANF

Policymakers should reverse the long-term decline in the value of federal TANF funding. They also should set standards to guard against extremely restrictive state eligibility policies that leave many of the families with the greatest needs — including, disproportionately, Black families — with neither employment nor cash assistance. In addition, they should set a minimum benefit level to ensure that all families, regardless of where they live, have access to cash benefits during times of need that will allow them to cover their most basic expenses. States should be required to spend any new federal resources they receive to meet the program’s core purposes: cash assistance, employment assistance, and work supports.

The TANF block grant has not been increased since its inception; as a result, it has lost 40 percent of its value due to inflation, as noted above. That fixed block grant funding and erosion, combined with TANF’s nearly unfettered state flexibility, narrowly defined work requirements, and time limits, have created a system in which very few families in need receive cash assistance or help preparing for success in today’s labor market.