Robust COVID Relief Achieved Historic Gains Against Poverty and Hardship, Bolstered Economy

End Notes

[1] Lennart Niermann and Ingo Pitterle, “The COVID-19 crisis: what explains cross-country differences in the pandemic’s short-term economic impact?” United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs, April 28, 2021, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/109165/1/MPRA_paper_109165.pdf.

[2] H. Luke Shaefer, Testimony Before the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis Hearing on the Impact of Pandemic Response, September 22, 2021, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/VC/VC00/20210922/114055/HHRG-117-VC00-Wstate-ShaeferH-20210922.pdf.

[3] Bernard Yaros, Jesse Rogers, Ross Cioffi, and Mark Zandi, “Fiscal Policy in the Pandemic,” Moody’s Analytics, February 24, 2022, https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/article/2022/global-fiscal-policy-in-the-pandemic.pdf.

[4] CBPP, “Policymakers Should Craft Compromise Build Back Better Package,” February 1, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/policymakers-should-craft-compromise-build-back-better-package.

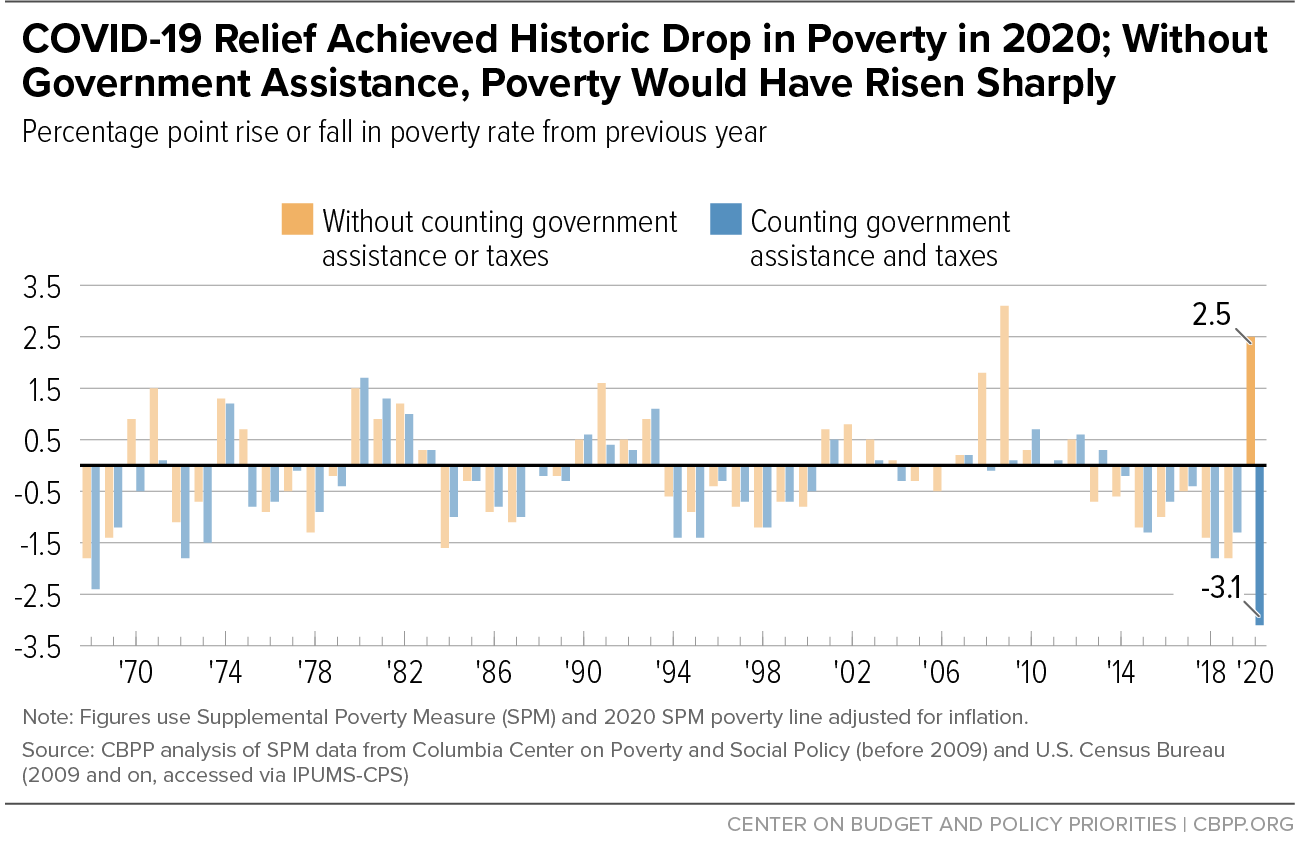

[5] Unless noted, poverty figures in this report use the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). CBPP analysis of the March Current Population Survey merged with historical SPM data produced by the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy. For methods used, see Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Economic Security Programs Reduce Overall Poverty, Racial and Ethnic Inequities,” CBPP, updated July 1, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-reduce-overall-poverty-racial-and-ethnic.

[6] Figures account for all public benefits (including permanent programs such as Social Security, food assistance, rental vouchers, regular state unemployment insurance, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, as well as pandemic programs such as Economic Impact Payments and supplemental unemployment benefits and food assistance), as well as federal and state income taxes and payroll taxes. The decrease in the percentage of people in poverty (from 11.8 percent to 9.1 percent) was also the largest on record.

[7] CBPP analysis of March 2020 and 2021 Current Population Survey. Figures are based on income before benefits and taxes. The increase in the percentage of people in poverty before counting government assistance and taxes (from 22.5 percent in 2019 to 25.3 percent in 2020) was also the second largest on record, with data back to 1967.

[8] Figures refer to the number of people whose family disposable income (i.e., SPM resources) for the year is below $40,000 in inflation-adjusted 2019 dollars when government assistance and taxes are not considered but above that threshold once assistance is included and taxes are subtracted.

[9] See, for example, Patrick Cooney and H. Luke Shaefer, “Material Hardship and Mental Health Following the Covid-19 Relief Bill and American Rescue Plan Act,” University of Michigan Poverty Solutions, May 2021, http://sites.fordschool.umich.edu/poverty2021/files/2021/05/PovertySolutions-Hardship-After-COVID-19-Relief-Bill-PolicyBrief-r1.pdf; Paul R. Shafer et al., “Association of the Implementation of Child Tax Credit Advance Payments With Food Insufficiency in US Households,” JAMA Network Open, January 13, 2022, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2788110; Lauren Bauer, Krista Ruffini, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “An Update on the Effect of Pandemic-EBT on Measures of Food Hardship,” Brookings Institution Hamilton Project, September 29, 2021, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/blog/an_update_on_the_effect_of_pandemic_ebt_on_measures_of_food_hardship;

Zachary Parolin et al., “The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material Hardship,” Columbia University Poverty and Social Policy Working Paper, September, 20, 2021, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/610831a16c95260dbd68934a/t/6148c84a76d7c27c418bcd13/1632159820347/Child-Tax-Credit-Expansion-on-Material-Hardship-CPSP-2021.pdf.

[10] For childless adults, food insufficiency also declined after the EIP payments (which they received) but not after the start of the monthly Child Tax Credit payments (which they did not receive), consistent with the conclusion that these and other relief policies eased hardship.

[11] Stefani Wendel, “State of Credit 2021: Rise in Scores Despite Pandemic Challenges,” Experian, September 7, 2021, http://www.experian.com/blogs/insights/2021/09/state-of-credit-2021/.

[12] Internal Revenue Service, “All third Economic Impact Payments issued,” January 26, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/all-third-economic-impact-payments-issued; Internal Revenue Service, “SOI Tax Stats – Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) Statistics,” June 28, 2021, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-coronavirus-aid-relief-and-economic-security-act-cares-act-statistics. These figures do not include households that did not receive payments as an “advance” but who received the amount as a credit on a tax return.

[13] Kalee Burns, Danielle Wilson, and Liana E. Fox, “Two Rounds of Stimulus Payments Lifted 11.7 Million People Out of Poverty During the Pandemic in 2020,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 14, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/09/who-was-lifted-out-of-poverty-by-stimulus-payments.html.

[14] Written Testimony of Charles P. Rettig, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, Before the Senate Finance Committee on the Filing Season and COVID-19 Recovery, April 13, 2021, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/written-testimony-of-charles-p-rettig-commissioner-internal-revenue-service-before-the-senate-finance-committee-on-the-filing-season-and-covid-19-recovery.

[15] These estimates reflect Pew Research Center estimates of the number of people and children under age 18 living in households containing people without a lawful immigration status (20.2 million), adjusted using data from the March 2019 Current Population Survey to match EIP eligibility criteria. See Jeffrey S. Passel and D’Vera Cohn, “U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Total Dips to Lowest Level in a Decade,” Pew Research Center, November 27, 2018, https://pewrsr.ch/3aNwutB.

[16] Chuck Marr et al., “Future Stimulus Should Include Immigrants and Dependents Previously Left Out, Mandate Automatic Payments,” CBPP, May 6, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/future-stimulus-should-include-immigrants-and-dependents-previously-left-out.

[17] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Effects of Selected Federal Pandemic Response Programs on Personal Income, June 2020,” July 31, 2020, effects-of-selected-federal-pandemic-response-programs-on-personal-income-june-2020.pdf (bea.gov).

[18] U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Unemployment Insurance, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims_arch.asp.

[19] Andrew Stettner and Elizabeth Pancotti, “1 in 4 Workers Relied on Unemployment Aid During the Pandemic,” Century Foundation, March 17, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/1-in-4-workers-relied-on-unemployment-aid-during-the-pandemic/?agreed=1.

[20] Lei Fang, Jun Nie, and Zoe Xie, “The CARES Act Unemployment Insurance Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, December 2020, https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/research/publications/policy-hub/2020/12/21/16-cares-act-unemployment-insurance-program-during-covid-19-pandemic.pdf.

[21] CBPP analysis of March 2021 Current Population Survey data using the SPM. Findings are similar when using the official poverty measure. Unemployment insurance protected 4.7 million people from falling below the official poverty line, according to the Census Bureau. For data by race and ethnicity, see Frances Chen and Em Shrider, “Expanded Unemployment Insurance Benefits During Pandemic Lowered Poverty Rates Across All Racial Groups,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 14, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/09/did-unemployment-insurance-lower-official-poverty-rates-in-2020.html.

[22] “The Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output,” Congressional Budget Office, September 18, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56537.

[23] Diana Farrell et al., “Consumption Effects of Unemployment Insurance during the Covid-19 Pandemic,” JPMorgan Chase, July 2020, https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/labor-markets/unemployment-insurance-covid19-pandemic.

[24] Shawn Donnan, Reade Pickert, and Madeline Campbell, “Covid Unemployment Benefits Show How Broken U.S. System Is,” Bloomberg, November 19, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-georgia-unemployment-bias/.

[25] Kyle Coombs et al., “Early Withdrawal of Pandemic Unemployment Insurance: Effects on Earnings, Employment and Consumption, Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 22-046, August 2021, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=61668.

[26] These larger credit amounts start to phase down to $2,000 for families with incomes above $112,500 for a head of household and $150,000 for a married couple. The $2,000 credit starts to phase down for families with incomes above $200,000 for a head of household and $400,000 for a married couple.

[27] Department of the Treasury, “By State: Advance Child Tax Credit Payments Distributed in December 2021,” December 15, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Advance-CTC-Payments-Disbursed-December-2021-by-State-12152021.pdf .

[28] Zachary Parolin, Sophie Collyer, and Megan A. Curran “Sixth Child Tax Credit Payment Kept 3.7 Million Children Out of Poverty in December,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Vol. 6, No. 1, January 18, 2022, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/61ea068f13dbfa56bfc9be17/1642727056209/Monthly-poverty-December-2021-CPSP.pdf; Zachary Parolin et al., “Absence of Monthly Child Tax Credit Leads to 3.7 Million More Children in Poverty in January 2022,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Vol. 6, No. 2, February 17, 2022, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/610831a16c95260dbd68934a/t/620ec869096c78179c7c4d3c/1645135978087/Monthly-poverty-January-CPSP-2022.pdf. Note that monthly and annual poverty-reduction calculations differ. The estimated monthly poverty impact of the expanded Child Tax Credit, for instance, does not include the lump-sum payments received at tax time, so monthly poverty reductions understate the eventual full-year effect of the credit.

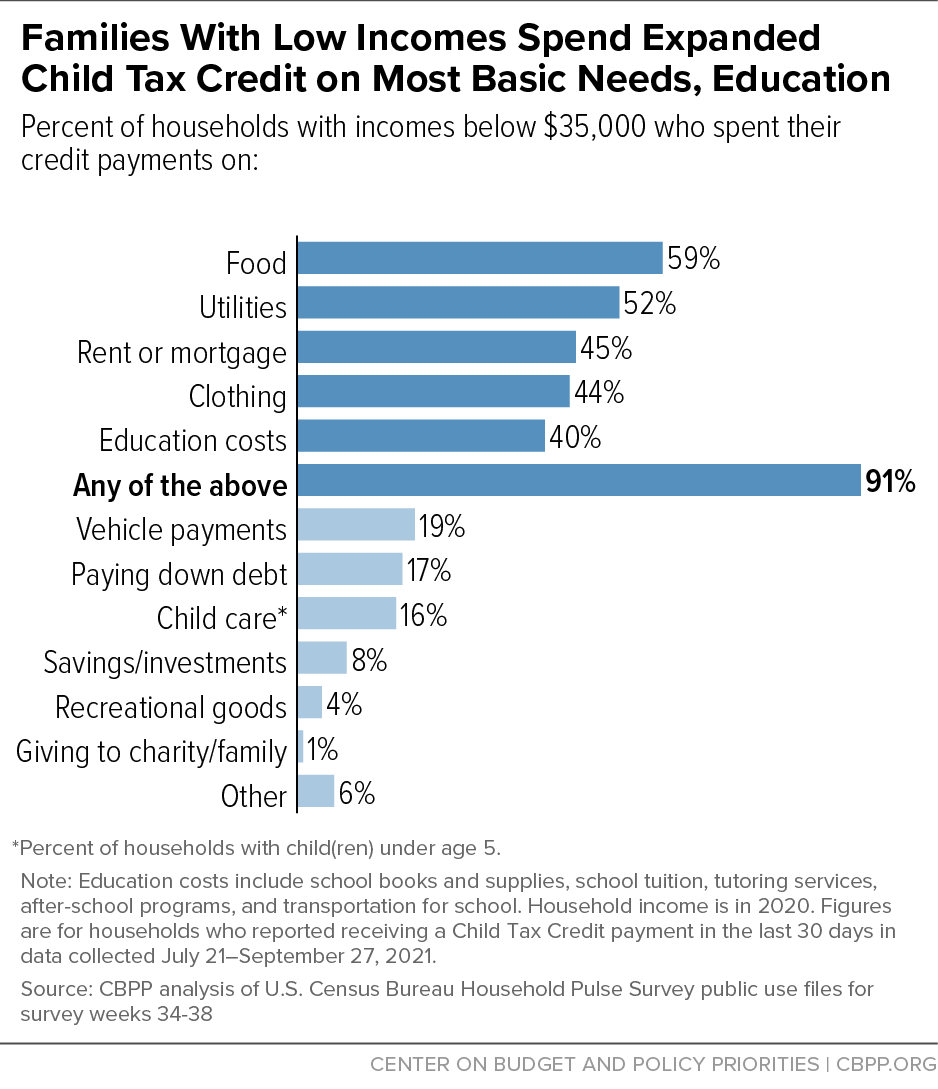

[29] Claire Zippel, “9 in 10 Families With Low Incomes Are Using Child Tax Credits to Pay for Necessities, Education,” CBPP, October 21, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/9-in-10-families-with-low-incomes-are-using-child-tax-credits-to-pay-for-necessities-education.

[30] Megan A. Curran, “Research Roundup of the Expanded Child Tax Credit: The First 6 Months,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Vol. 5. No. 5, December 22, 2021, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/610831a16c95260dbd68934a/t/61f946b1cb0bb75fd2ca03ad/1643726515657/Child-Tax-Credit-Research-Roundup-CPSP-2021.pdf

[31] Kris Cox et al., “If Congress Fails to Act, Monthly Child Tax Credit Payments Will Stop, Child Poverty Reductions Will Be Lost,” CBPP, updated December 3, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/if-congress-fails-to-act-monthly-child-tax-credit-payments-will-stop-child.

[32] National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, “A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty,” 2019, https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25246/a-roadmap-to-reducing-child-poverty.

[33] See Arloc Sherman et al., “Recovery Proposals Adopt Proven Approaches to Reducing Poverty, Increasing Social Mobility,” CBPP, August 5, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/recovery-proposals-adopt-proven-approaches-to-reducing-poverty; Claire Zippel and Arloc Sherman, “Bolstering Family Income Is Essential to Helping Children Emerge Successfully From the Current Crisis,” CBPP, updated February 25, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/bolstering-family-income-is-essential-to-helping-children-emerge.

[34] Jessica Banthin and John Holahan, “Making Sense of Competing Estimates: The COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Health Insurance Coverage,” Urban Institute, August 2020, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102777/making-sense-of-competing-estimates_1.pdf

[35] Jared Ortaliza et al., “How Does Cost Affect Access to Care?” Peterson-KFF Health Systems Tracker, January 14, 2022, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/cost-affect-access-care/.

[36] Joel Ruhter et al., “Tracking Health Insurance Coverage in 2020-2021,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, October 29, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/tracking-health-insurance-coverage.

[37] Medicaid.gov, “Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Application, Eligibility Determination, and Enrollment Reports & Data,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/monthly-medicaid-chip-application-eligibility-determination-and-enrollment-reports-data/index.html. July 2021 data are preliminary.

[38] Gideon Lukens, “Medicaid Coverage Gap Affects Even Larger Group Over Time Than Estimates Indicate,” CBPP, September 3, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/9-3-21health.pdf. Black and Latino people are more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid largely because they are more likely to live in low-income families, a legacy of unequal opportunities due to racism and discrimination. It is uncertain why Latino people experience more frequent disruptions in Medicaid coverage, but reasons could include higher rates of income volatility or administrative obstacles to renewing coverage.

[39] D. Keith Branham et al., “Access to Marketplace Plans with Low Premiums on the Federal Platform: Part II,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 1, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/access-marketplace-plans-low-premiums-uninsured-american-rescue-plan. Estimates are for uninsured non-elderly adults potentially eligible for marketplace coverage in Healthcare.gov states.

[40] Tara Straw, “Marketplace Poised for Further Gains as Open Enrollment Begins,” CBPP, October 29, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/marketplaces-poised-for-further-gains-as-open-enrollment-begins.

[41] “Marketplace 2022 Open Enrollment Period Report: Final National Snapshot,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), January 27, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/marketplace-2022-open-enrollment-period-report-final-national-snapshot; Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files, 2020 and 2021; “Biden-Harris Administration Announces 14.5 Million Americans Signed Up for Affordable Health Care During Historic Open Enrollment Period,” CMS, January 27, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-announces-145-million-americans-signed-affordable-health-care-during.

[42] Robin A. Cohen and Amy E. Cha, “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Quarterly Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, July 2020-September 2021,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), January 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/Quarterly_Estimates_2021_Q13.pdf; Robin A. Cohen et al., “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, 2020,” CDC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, August 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur202108-508.pdf.

[43] Joel Ruhter et al., “Tracking Health Insurance Coverage in 2020-2021,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, October 29, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/tracking-health-insurance-coverage

[44] Jessica Schubel, “States Are Leveraging Medicaid to Respond to COVID-19,” CBPP, updated September 2, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-leveraging-medicaid-to-respond-to-covid-19.

[45] Jennifer Sullivan, “States Are Using One-Time Funds to Improve Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services, But Longer-Term Investments Are Needed,” CBPP, September 23, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-using-one-time-funds-to-improve-medicaid-home-and-community-based.

[46] Judith Solomon, “Medicaid Needs Direct Funding to Providers and More Federal Funds for States,” CBPP, June 10, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-needs-direct-funding-to-providers-and-more-federal-funds-for-states.

[47] Sharon Parrott et al., “Immediate and Robust Policy Response Needed in Face of Grave Risks to the Economy,” CBPP, March 19, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/immediate-and-robust-policy-response-needed-in-face-of-grave-risks-to-the-economy.

[48] Government Accountability Office, “Continued Attention Needed to Enhance Federal Preparedness, Response, Service Delivery, and Program Integrity,” July 2021, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-551.pdf.

[49] Stefan Pichler, Katherine Wen, and Nicholas R. Ziebarth, “COVID-19 Emergency Sick Leave has Helped Flatten the Curve in the United States,” Health Affairs, Vol. 39, No. 12, October 15, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00863.

[50] Rachel Garg et al., “A new normal for 2-1-1 food requests?” Washington University in St. Louis Health Communication Research Laboratory, June 15, 2020, https://hcrl.wustl.edu/a-new-normal-for-2-1-1-food-requests/; Cindy Charles et al., “Trends of top 3 food needs during COVID,” Washington University in St. Louis Health Communication Research Laboratory, August 7, 2020, https://hcrl.wustl.edu/trends-of-top-3-food-needs-during-covid/.

[51] Paul Morello, “The food bank response to COVID, by the numbers,” Feeding America, March 12, 2021, https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-blog/food-bank-response-covid-numbers.

[52] According to annual food insecurity data from the December 2020 Food Security Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS-FSS), 10.5 percent of U.S. households were food insecure in 2020. While the overall prevalence of food insecurity was unchanged from 2019, it increased for households with children and Black households. The number of individuals in food-insecure households also increased by 3 million, from 35.2 million in 2019 to 38.3 million in 2020.

The CPS-FSS includes a measure of food insecurity, based on ten to 18 questions about conditions and behaviors related to difficulty meeting food needs. This measure is different from the food insufficiency measure in the Household Pulse Survey, which is based on a single question about the household having enough food to eat in the past seven days. While the food insecurity figures from the CPS-FSS appear to show lower rates of food hardship during 2020 than the Household Pulse Survey, more research is needed to assess the impact of differences in reference periods, mode of data collection, response rates, and other factors on reported food hardship. See Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2020,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, September 2021, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=102075.

[53] Through SNAP, all states have provided Emergency Allotments (EA), which Congress authorized in March 2020, and all but a handful of states continue to provide them. USDA may approve states to provide EAs for as long as the federal government has declared a public health emergency and the state has issued an emergency or disaster declaration. In states providing EAs, all households receive the maximum benefit for their household size; if the difference between the maximum benefit and the household’s original benefit under the SNAP benefit formula is less than $95, then the household’s EA is increased so the total EA benefit is no lower than $95. See USDA, “USDA Increases Emergency SNAP Benefits for 25 million Americans,” April 1, 2021, https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/usda-006421. Families First and the American Rescue Plan provided funding for additional commodity purchases for emergency food programs and increased funding for the nutrition assistance block grants in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

[54] For a description of the temporary flexibilities in SNAP, see CBPP, “States Are Using Much-Needed Temporary Flexibility in SNAP to Respond to COVID-19 Challenges,” updated October 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/states-are-using-much-needed-temporary-flexibility-in-snap-to-respond-to.

[55] When the federal public health emergency ends, the temporary SNAP benefit increases will end, but due to a permanent change in the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), SNAP benefits will remain higher than before the pandemic, averaging roughly $170 per person per month. In August 2021, USDA announced a revision of the TFP, which raised maximum SNAP benefits by 21 percent compared to what they would have been beginning in October 2021 (and in future years). See “USDA Modernizes the Thrifty Food Plan, Updates SNAP Benefits,” USDA, August 16, 2021, https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/usda-0179.21; and Joseph Llobrera, Matt Saenz, and Lauren Hall, “USDA Announces Important SNAP Benefit Modernization,” CBPP, August 26, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/usda-announces-important-snap-benefit-modernization.

[56] See Appendix A of Elaine Waxman et al., “Documenting Pandemic EBT for the 2020-21 School Year,” Urban Institute, October 26, 2021, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/documenting-pandemic-ebt-2020-21-school-year/view/full_report for a timeline of when various aspects of the Pandemic-EBT program were adopted in federal law.

[57] Prior to the pandemic, children received $9 per month and women received $11 per month for fruit and vegetables. During the summer of 2021, the fruit and vegetable benefit was increased to $35 per month for women and children for a four-month period. Since October 2021, children receive $24 monthly, pregnant and postpartum individuals receive $43 monthly, and breastfeeding individuals receive $47 monthly. These increases are in effect through March 31, 2022, under P.L. 117-70.

[58] Lauren Bauer et al., “An Update on the Effect of Pandemic EBT on Measures of Food Hardship,” Brookings Institution Hamilton Project, September 29, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/research/an-update-on-the-effect-of-pandemic-ebt-on-measures-of-food-hardship/. As explained in the technical appendix, households were considered to have very low food security among children if they reported that the children sometimes or often did not eat enough in the last seven days because the household could not afford food. Households that experienced food insufficiency reported that they were sometimes or often not able to get enough to eat in the previous seven days.

[59] The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of “individual” refers to a person who is not part of a family with children during an episode of homelessness. Individuals may be homeless as single adults, unaccompanied youth, or in multiple-adult or multiple-child households.

[60] Meghan Henry et al., “The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 1,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, January 2021, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

[61] Renter households with worst case housing needs are those with very low incomes (no more than 50 percent of the area median income) who receive no government housing assistance and pay more than half of their income for rent, live in severely inadequate conditions, or both.

[62] California Project Roomkey: https://www.cdss.ca.gov/inforesources/cdss-programs/housing-programs/project-roomkey; Shelter Guidance: https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/Non-Congregate-Approaches-to-Sheltering-for-COVID-19-Homeless-Response.pdf and https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/CPD/documents/Model-Transitions-Document_FINAL.pdf; King County: https://kingcounty.gov/depts/health/covid-19/providers/~/media/depts/health/communicable-diseases/documents/C19/hch/shelter-in-place-guidance.ashx.

[63] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Emergency Rental Assistance Program,” https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/emergency-rental-assistance-program.

[64] Jacob Haas et al., “Preliminary Analysis: Eviction Filing Trends After the CDC Moratorium Expiration,” Eviction Lab, December 9, 2021, https://evictionlab.org/updates/research/eviction-filing-trends-after-cdc-moratorium/.

[65] Data posted as of January 16, 2022. https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/ehv/dashboard.

[66] CBPP analysis of Census’ Household Pulse Survey public use file, data collected December 1-December 13, 2021.

[67] On December 27, 2020, when most of the funds were allocated, Congress extended the deadline, allowing states and populous cities and counties to use the funds to cover costs incurred through the end of 2021.

[68] Alan Berube, Christiana K. McFarland, and Teryn Zmuda, “How Communities Are Investing American Rescue Plan funds with the Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker,” Brookings Institution, February 3, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2022/02/03/how-communities-are-investing-american-rescue-plan-funds-with-the-local-government-arpa-investment-tracker/.

[69] For a summary of state and local fiscal recovery funds (SLFRF) spending, see Ed Lazere, “How States Can Best Use Federal Fiscal Recovery Funds: Lessons From State Choices So Far,” CBPP, November 29, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/how-states-can-best-use-federal-fiscal-recovery-funds-lessons-from.

[70] Court rulings have stopped this prohibition from having effect in some states.

[71] For example, the governors of Mississippi and West Virginia both announced their support for eliminating income taxes shortly after the November 2020 election, before the American Rescue Plan was adopted. And conservative policy makers in several states have called for income tax cuts for years, and in many cases have enacted them.

[72] In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Kansas, Maine, North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin all enacted large income tax cuts, and several other states enacted income tax cuts that were smaller as a share of the revenues. In all, between 2008 and 2019, 18 states enacted personal income tax rate cuts and 17 states (plus Washington, D.C.) enacted corporate income tax rate cuts. See Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: Still a Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” CBPP, May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-personal-income-tax-cuts-still-a-poor-strategy-for-economic. See also Michael Leachman and Erica Williams, “States Can Learn From Great Recession, Adopt Forward-Looking, Antiracist Policies,” CBPP, February 11, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/2-11-21sfp.pdf.

[73] City of Pittsburgh Recovery Plan, State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, https://apps.pittsburghpa.gov/redtail/images/15563_SLFRF-Recovery-Plan-Performance-Report_8.31.2021.pdf.

[74] City of St. Louis, MO 2021 Recovery Plan, State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, August 31, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/St.Louis_2021-Recovery-Plan_SLT-2835.pdf. For a summary of the plans described in city and county SLFRF reports in August 2021, see the Brookings Institution, “Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker, February 3, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/arpa-investment-tracker/.

[75] See Joshua Marshall, “Tribal Nations More Vulnerable to COVID-19 Impacts, Need Additional Fiscal Aid,” CBPP, August 5, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/tribal-nations-more-vulnerable-to-covid-19-impacts-need-additional-fiscal-aid.

[76] The Navajo Nation, Office of the President and Vice President, “Initial Distribution of ARPA Fiscal Recovery Funds Allocated,” press release issued October 13, 2021, https://navajonationarpa.org/hidden/press-releases/53-for-immediate-release-initial-distribution-of-arpa-fiscal-recovery-funds-allocated/file.

[77] “Puerto Rico to Receive Massive $2.47 Billion As Part of the American Rescue Plan 2021,” El American, June 9, 2021, https://elamerican.com/puerto-rico-receive-billion-rescue-plan/. See also “Gobernador anuncia distribucion millonaria de fondos ARPA,” La Fortaleza, August 3, 2021, https://www.fortaleza.pr.gov/comunicados/gobernador-anuncia-distribucion-millonaria-de-fondos-arpa.

[78] Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, “A most unusual recovery: How the US rebound from COVID differs from rest of G7,” Brookings Institution, December 8, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/12/08/a-most-unusual-recovery-how-the-us-rebound-from-covid-differs-from-rest-of-g7/#cancel.

[79] The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-123), and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (P.L. 116-127), which increased federal funding for some federal agencies and for state and local governments, required employers to grant paid sick leave to employees, and provided payments and tax credits to employers. The CARES Act (P.L. 116-136) provided loans to businesses, payments to health care providers, payments and tax credits to individuals, additional funding to state and local governments, and reductions in certain business taxes. Finally, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and Health Care Enhancement Act (P.L. 116-139) increased federal funding for the loans to businesses and payments to health care providers supplied in the CARES Act.

[80] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that without the relief policies, GDP would have shrunk by 10 percent between 2019 and 2020 and risen by 5 percent between 2020 and 2021 (compared with -5.8 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively, in the July 2020 projections that include the effects of policy). These growth estimates imply that the level of GDP in 2020 and 2021 would be roughly 12 percent and 9 percent lower, respectively, without the relief measures. “The Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output,” Congressional Budget Office, September 18, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56537.

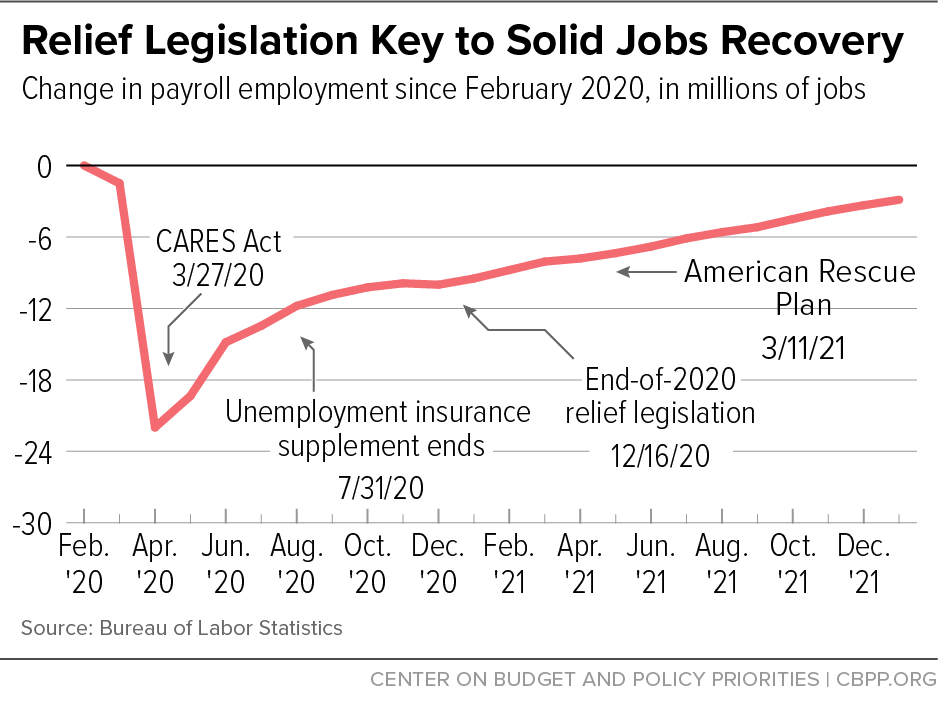

[81] These relief and recovery measures also boosted job growth. While nonfarm payroll employment was still 3.6 million jobs lower at the end of 2021 than at the start of the recession in February 2020, actual job losses were substantially lower than CBO projected they would be. In the fourth quarter of 2021, payroll employment was 3 million jobs below its pre-pandemic level in the fourth quarter of 2019, while CBO projected in July 2020 — before enactment of the December package and the American Rescue Plan — that the shortfall would be 7 million jobs.

[82] The National Bureau of Economic Research, the acknowledged arbiter of business dating, has determined that the pandemic recession lasted two months, from the previous peak in February 2020 through April 2020. On a quarterly basis, the NBER determined that the recession lasted two quarters, from the previous peak in the fourth quarter of 2019 through the second quarter of 2020.

[83] Bernard Yaros, Jesse Rogers, Ross Cioffi, and Mark Zandi, “Fiscal Policy in the Pandemic,” Moody’s Analytics, forthcoming.

[84] Congressional Budget Office, “Additional Information About the Updated Budget and Economic Outlook: 2021 to 2031,” Figure 2-1, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57373#_idTextAnchor084.

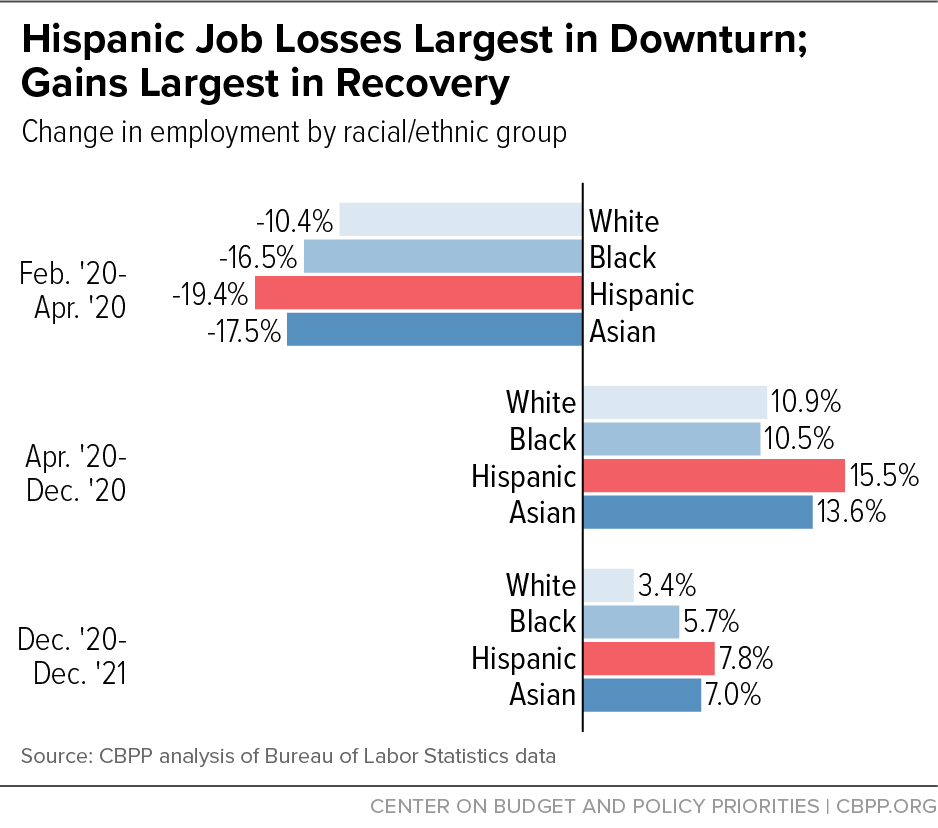

[85] The recovery from the large job losses between February 2020 and April 2020 has generally been largest for the same groups that experienced the deepest losses, but in many cases, all of the recession losses have not yet been made up. For example, while the share of Hispanic workers with a job in December 2021 was 0.3 percent higher than in February 2020, Hispanic women’s employment was still 0.6 percent below what it was in February 2020.

[86] Employment Cost Index calculations reported in Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III, “ US wages grew at fastest pace in decades in 2021, but prices grew even more,” Peterson Institution for International Economics, January 28, 2022, https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/us-wages-grew-fastest-pace-decades-2021-prices-grew-even-more.

[87] See, for example, Paul Krugman, “The Secret Triumph of Economic Policy,” New York Times, January 13, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/13/opinion/pandemic-economic-recovery.html.