Marketplaces Poised for Further Gains as Open Enrollment Begins

End Notes

[1] CBPP calculations using American Community Survey for 2013, 2016, and 2019.

[2] Department of Health and Human Services, “2021 Final Marketplace Special Enrollment Period Report,” October 20, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-sep-final-enrollment-report.pdf. In 2021, 14 states and the District of Columbia run their own health insurance marketplaces rather than relying on HealthCare.gov.

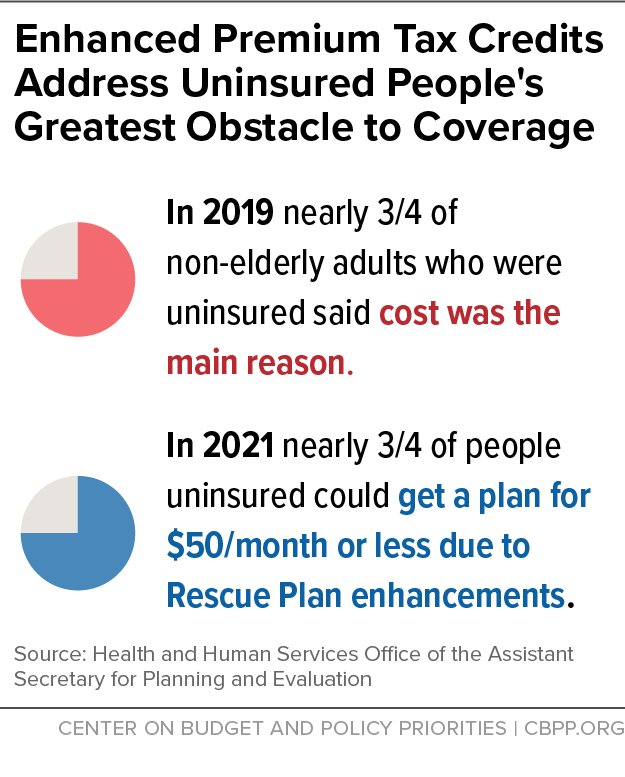

[3] Amy E. Cha and Robin A. Cohen, “Reasons for Being Uninsured Among Adults Aged 18–64 in the United States, 2019,” NCHS Data Brief No. 382, September 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db382.htm.

[4] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), “Access to Marketplace Plans with Low Premiums on the Federal Platform: Availability Among Uninsured Non-Elderly Adults under the American Rescue Plan,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 31, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/access-marketplace-plans-low-premiums-uninsured-american-rescue-plan.

[5] 2021 Final Marketplace Special Enrollment Period Report.

[6] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2021 Open Enrollment Report,” Department of Health and Human Services, April 21, 2021, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/health-insurance-exchanges-2021-open-enrollment-report-final.pdf.

[7] Karen Pollitz et al., “Consumer Assistance in Health Insurance: Evidence of Impact and Unmet Need,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 7, 2020, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/consumer-assistance-in-health-insurance-evidence-of-impact-and-unmet-need/.

[8] Tara Straw, “HealthCare.gov Enrollment Climbs With Biden Administration Actions,” CBPP, June 14, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/healthcaregov-enrollment-climbs-with-biden-administration-actions.

[9] ASPE, “Reaching the Remaining Uninsured: An Evidence Review on Outreach & Enrollment,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, October 1, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/reaching-remaining-uninsured-outreach-enrollment.

[10] This included a combination of television, radio, direct response (text messaging, email, and autodial), internet search buys, and paid digital ads, and reflected the results of a partial open enrollment period. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Preliminary OE4 Lessons Learned,” https://downloads.cms.gov/files/359411146-preliminary-oe4-lessons-learned.pdf.

[11] Peter V. Lee et al., “Marketing Matters: Lessons From California to Promote Stability and Lower Costs in National and State Individual Insurance Markets,” Covered California, September 2017, https://hbex.coveredca.com/data-research/library/CoveredCA_Marketing_Matters_9-17.pdf.

[12] Paul R. Shafer et al., “Television Advertising and Health Insurance Marketplace Consumer Engagement in Kentucky: A Natural Experiment,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, October 2018, https://www.jmir.org/2018/10/e10872/PDF.

[13] Naoki Aizawa and You Suk Kim, “Public and Private Provision of Information in Market-Based Public Programs: Evidence from Advertising in Health Insurance Marketplaces,” NBER Working Paper No. 27695, revised April 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27695.

[14] Shafer et al.

[15] Jacob Goldin, Ithai Z Lurie, and Janet McCubbin, “Health Insurance and Mortality: Experimental Evidence from Taxpayer Outreach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 2021, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/136/1/1/5911132.

[16] Keith M. Marzillio Ericson, “Nudging Leads Consumers In Colorado to Shop But Not Switch ACA Marketplace Plans,” Health Affairs, February 2017, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0993.

[17] Rebecca Myerson et al., “The Impact of Personalized Telephone Outreach on Health Insurance Take-up: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial,” ASHEcon virtual conference, June 22, 2021, https://ashecon.confex.com/ashecon/2021/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/10422.

[18] Michael R. Cousineau, Gregory D. Stevens, and Albert Farias, “Measuring the Impact of Outreach and Enrollment Strategies for Public Health Insurance in California,” Health Services Research, February 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3037785/.

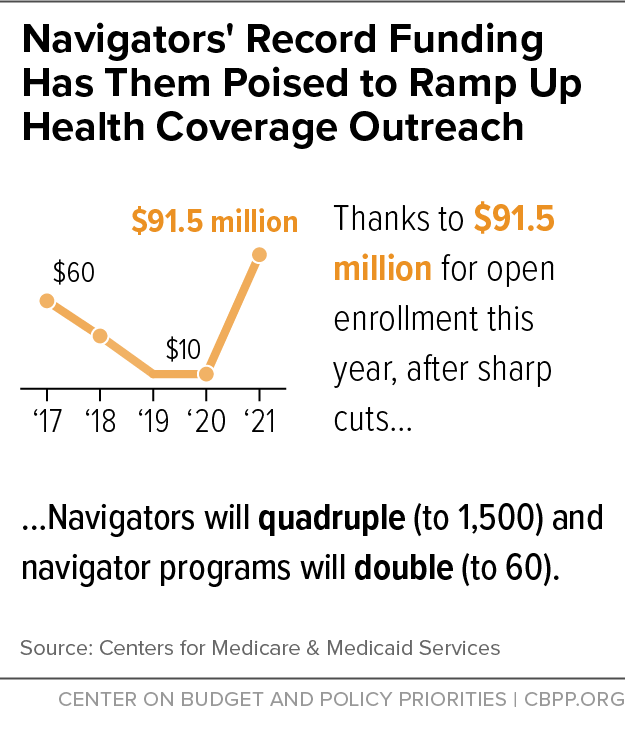

[19] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Biden-Harris Administration Quadruples the Number of Health Care Navigators Ahead of HealthCare.gov Open Enrollment Period,” Press Release, August 27, 2021, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-quadruples-number-health-care-navigators-ahead-healthcaregov-open.

[20] ASPE, “Reaching the Remaining Uninsured.”

[21] Karen Pollitz, Jennifer Tolbert, and Ashley Semanskee, “2016 Survey of Health Insurance June 2016 Marketplace Assister Programs and Brokers,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2016, https://files.kff.org/attachment/2016-Survey-of-Marketplace-Assister-Programs-and-Brokers.

[22] CBPP, “Reviving Longer Open Enrollment Periods Could Enable More to Gain Coverage,” April 19, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/reviving-longer-open-enrollment-periods-could-enable-more-to-gain-coverage.

[23] Katherine Swartz and John A. Graves, “Shifting the Open Enrollment Period for ACA Marketplaces Could Increase Enrollment and Improve Plan Choices,” Health Affairs, July 2014, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0007.

[24] Matthew Buettgens, Stan Dorn, and Hannah Recht, “More than 10 Million Uninsured Could Obtain Marketplace Coverage through Special Enrollment Periods,” Urban Institute, November 2015, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/74561/2000522-More-than-10-Million-Uninsured-Could-Obtain-Marketplace-Coverage-through-Special-Enrollment-Periods.pdf. Laurel Lucia, “How Do We Make Special Enrollment Periods Work?” Health Affairs Blog, February 16, 2016, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20160216.053180/full/.

[25] Congressional Budget Office, Letter to Honorable Jason Smith, October 19, 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-10/Letter_Honorable_Jason_Smith.pdf. This analysis of additional annual enrollment was based on the House Ways and Means Committee proposal for a permanent extension of expanded premium tax credits.

[26] Judith Solomon, “Federal Action Needed to Close Medicaid ‘Coverage Gap,’ Extend Coverage to 2.2 Million People,” CBPP, May 6, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/federal-action-needed-to-close-medicaid-coverage-gap-extend-coverage-to-22-million.

[27] Judith Solomon, “Build Back Better Legislation Would Close the Medicaid Coverage Gap,” CBPP, September 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/build-back-better-legislation-would-close-the-medicaid-coverage-gap.

[28] Laura Harker, “Closing the Coverage Gap a Critical Step for Advancing Health and Economic Justice,” CBPP, October 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/closing-the-coverage-gap-a-critical-step-for-advancing-health-and-economic-justice.