On November 1, 2020 the Trump Administration approved a Section 1332 State Innovation Waiver permitting Georgia to leave the federal health insurance marketplace beginning in 2023 and instead advise people to enroll directly with insurers or through online enrollment vendors or agents or brokers. The waiver proposal was flawed from the start[2] but is now even more clearly in violation of the statutory approval criteria, or “guardrails,” because it would result in fewer Georgians getting health coverage than would be the case without the waiver. The Biden Administration, which is currently re-examining Georgia’s waiver, should stop the state from leaving the federal marketplace by revoking federal approval to implement this harmful change.

Changes in federal law and policies have greatly increased marketplace enrollment, outstripping the estimates Georgia submitted with its waiver application. This is critical because 1332 waivers must meet a coverage guardrail, which requires the state to demonstrate that at least a comparable number of people will have health coverage under its waiver plan as would have had health coverage without the waiver. Neither the assumptions Georgia made about coverage levels absent the waiver (the baseline) nor its projections of the waiver’s coverage impacts bear any resemblance to reality. Moreover, Georgia rebuffed two requests for an updated analysis to account for these factors, adding to the ample reasons why the Biden Administration should revoke the waiver.

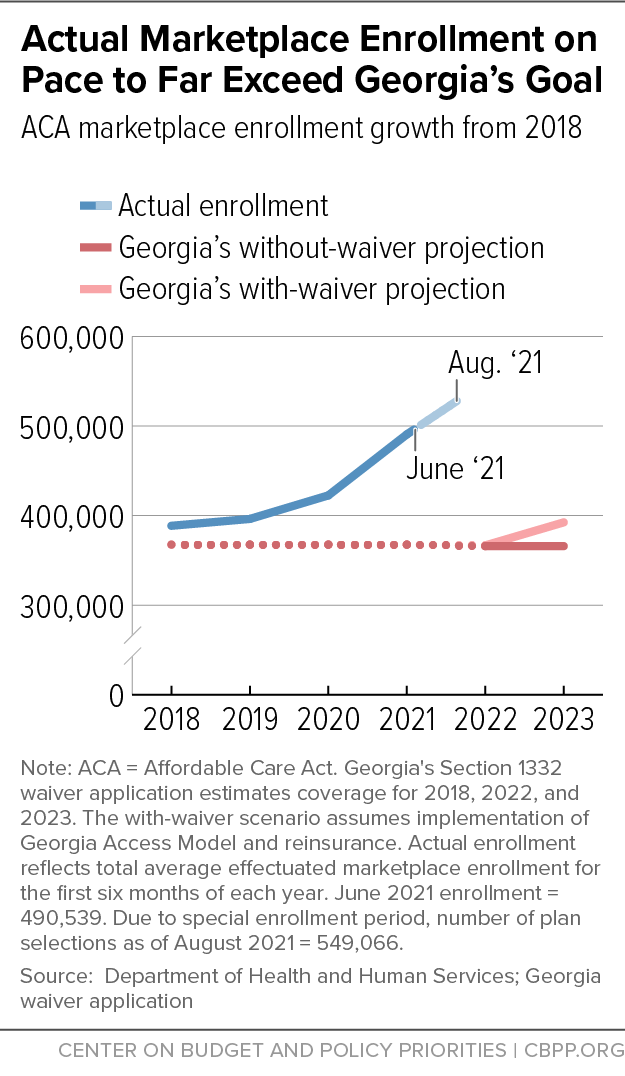

In its application, Georgia painted a bleak view of the future of the marketplace and claimed that the waiver was necessary to stem enrollment losses. But even before the waiver was approved, the tide turned, and the state’s baseline projections, based on the 2018 plan year, are now wildly off target. Georgia’s marketplace enrollment is more than 180,000 higher in August 2021 than in 2018 — a roughly 50 percent increase.[3] And new federal laws, regulations, and policies in place to support enrollment have fueled, and will likely sustain, these enrollment gains.

These changes both to policy and to actual enrollment require a new analysis of Georgia’s already flawed waiver. In particular, a new analysis would find that the waiver cannot meet the statutory coverage guardrail. HealthCare.gov is positioned to maintain or grow its record enrollment through the Administration’s implementation of various laws, regulations, and policies, including renewed federal support for important functions such as marketing and enrollment assistance. In contrast, the Georgia model would forgo this expanded federal investment and abandon the success of HealthCare.gov. This would disrupt the enrollment process and lead to substantial coverage losses. Even if Georgia’s own enrollment estimates are assumed to be true, its waiver would lead to more people being uninsured than would be true absent the waiver.

The Administration can terminate the waiver not just for its violation of statutory protections but also based on administrative and procedural grounds. The state contends that the Department of Health and Human Services and Department of the Treasury (“Departments”) don’t have the authority to ask for further analysis, but this is clearly wrong under the statute, federal regulations, and the waiver approval agreement the state signed. All require ongoing compliance, including updated analyses the state must submit upon request. By not complying, Georgia has failed to meet these requirements. Both the 1332 regulations and the terms of the waiver itself expressly list termination as a possible consequence.

Georgia’s plan to eliminate HealthCare.gov always violated the 1332 guardrails, as explained further below. It would create confusion among enrollees, deny enrollment help to some people eligible for Medicaid under state law, and lead more people into low-value plans that don’t meet the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) protections. Recent developments, which must be part of an updated analysis of the waiver, provide additional reasons the Administration should stop Georgia’s plan.

On November 1, 2020 the Trump Administration approved Georgia’s Section 1332 waiver for what the state calls the Georgia Access Model.[4] The ACA’s Section 1332 allows a state to obtain permission to waive parts of the law and design its own health coverage program as long as the proposal meets certain statutory guardrails. If the waiver reduces federal costs, the state can receive federal funds equal to those savings, known as pass-through payments. (See box, “Standards for 1332 Waivers.”)

The Georgia Access Model would eliminate Georgians’ access to HealthCare.gov — a centralized shopping platform that displays and allows enrollment in all marketplace health plans — without creating a comparable state substitute.[5] Instead, beginning in 2023, Georgia would scatter marketplace functions for more than half a million enrollees among a multitude of private brokers and health insurers, akin to the insurance market prior to the ACA. The state would also rely on these private entities to conduct marketing and outreach, in place of federal investments in these activities which have proven highly effective. People could still enroll in plans that would have been available through HealthCare.gov, and access federal subsidies if they qualify, but this process would be more difficult, and many other plans that do not meet ACA standards and are not eligible for subsidies would also be on offer. The state’s actuarial analysis, required for states seeking a 1332 waiver, projected the Georgia Access Model would modestly increase marketplace enrollment in 2023 and slightly lower premiums compared to a 2018 baseline.[6] But this analysis was flawed when first released and is even more implausible now.

In letters dated June 3 and July 30 of 2021, the Departments under the Biden Administration asked the state for a revised actuarial analysis to account for changes in federal law and policy that significantly raised the baseline against which the waiver must be judged. Georgia refused to update its analysis and challenged the federal government’s authority to ask for the revision. The Departments are asking for public comment on the validity of the state’s data and whether the Georgia Access Model complies with the statutory guardrails, which are designed to ensure that at least as many people are covered under the waiver as would have been the case without it and that the coverage meets ACA standards for comprehensiveness and affordability and does not increase federal costs.

Standards for 1332 Waivers

States’ 1332 waiver proposals must satisfy four statutory requirements to obtain federal approval. These guardrails are intended to ensure that state residents will be no worse off than they would be without the waiver.

The ACA requires states to demonstrate their proposals will meet the following standards.

- Comprehensiveness: Providing coverage at least as comprehensive as that provided through ACA marketplaces;

- Affordability: Providing coverage and out-of-pocket cost protections at least as affordable as those provided by the ACA;

- Coverage: Providing coverage to at least a comparable number of state residents as the ACA; and

- Deficit neutrality: Not increasing the federal deficit.

If a state’s 1332 waiver reduces the federal premium tax credits, cost-sharing reductions, or small business tax credits that a state’s residents and businesses qualify for, relative to what they would have received without the waiver (the baseline), the state may receive funding from the federal government up to the amount of financial assistance its residents would otherwise have received (reduced by any other costs the waiver imposes on the federal government). States can use these pass-through payments to provide financial assistance or other benefits to consumers different from those available under the ACA.

States implementing 1332 waivers must stay in compliance with all applicable federal laws, regulations, and interpretive guidance published by the Departments. In addition, approvals delineate a series of Specific Terms and Conditions agreed to by the Departments and the state, which typically state the grounds upon which a waiver can be amended, suspended, or terminated.

Section 1332 waivers are required to cover in each year at least a comparable number of people as would be the case without the waiver. Georgia’s waiver application was built around the premise that, unless the state intervened, marketplace enrollment would decline from its 2018 level, an already low enrollment count after deep cuts to marketing, outreach, and in-person assistance by the Trump Administration. But HealthCare.gov has been more effective than Georgia’s baseline assumed. Enrollment rebounded in the 2019 and 2020 plan years as premiums stabilized, showing the waiver’s projections were wrong before it was even approved. Then enrollment reached a historic high with the 2021 special enrollment period and Biden Administration investments.

Georgia’s own goals under the waiver can’t produce enrollment comparable to today’s coverage numbers. The waiver’s projection was that it would increase marketplace enrollment from about 366,000 in 2018 to 392,000 in 2023.[7] Even if Georgia’s waiver could generate those coverage gains over 2018, those gains would be well short of the 549,000 enrolled as of August 2021, meaning the waiver’s implementation would leave a huge coverage reduction and more people uninsured. (See Figure 1.) Any reasonable, updated analysis of the state’s waiver would also show that it can’t match, let alone surpass, today’s enrollment baseline. That’s true in part because the waiver would eliminate federal investments in the marketing, outreach, and in-person assistance that have proven to be effective in expanding coverage in the marketplace in recent years.[8]

Changes in Rules and Law Boost Enrollment Beyond Georgia’s Baseline

New federal statutes and regulations have increased coverage numbers prior to implementation of the Georgia Access Model and will continue to promote strong enrollment that the state has not accounted for in its baseline. The historically high enrollment figures that must be factored into the baseline make it highly unlikely the state’s plan could meet or exceed the coverage guardrail. And if Congress passes economic-recovery legislation it is now considering, its provisions would only add to the reasons that Georgia’s waiver violates 1332 standards. (See box, “Georgia’s Waiver Clearly Deficient if Build Back Better Becomes Law.”)

The American Rescue Plan, enacted in 2021, boosts the premium tax credit to reduce marketplace insurance premiums across the board in 2021 and 2022 and extends eligibility to people with incomes above 400 percent of the poverty line. It lowered premiums nationwide, and by 54 percent for existing enrollees in Georgia, which was one factor that led to robust marketplace enrollment in 2021 — a trend likely to continue in 2022.[9] While the premium tax credit enhancements are currently set to end in 2022, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts an enrollment “tail” as more people stay enrolled compared to the baseline without the Rescue Plan.[10] HealthCare.gov’s historically strong enrollment retention could also buoy coverage levels. In the 2021 open enrollment period — prior to enactment of the Rescue Plan — 77 percent were returning enrollees.[11] Even if subsidies return to pre-Rescue Plan levels, most HealthCare.gov enrollees would likely be eligible for zero-premium or low-premium plans to make coverage affordable. In Georgia, 80 percent of 2021 enrollees were eligible for such plans before the Rescue Plan’s premium enhancements took effect.[12] Georgia’s analysis does not account for these enrollment increases.

In addition, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act created a Medicaid continuous coverage requirement under which states, in exchange for getting a higher federal matching percentage of Medicaid costs covered, must keep Medicaid-eligible people enrolled for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency. CBO anticipates that the provision will begin to unwind in July 2022. As it does, some people whose income is too high for Medicaid might qualify for a premium tax credit in the marketplace and, if the system works well, will enroll in marketplace coverage. But Georgia’s analysis does not account for it.

Several new marketplace regulations finalized in September will encourage enrollment and retention, especially among low-income people, and are not accounted for in Georgia’s baseline enrollment projections. First, the federal marketplace will extend the open enrollment period by 30 days, to January 15. Research shows that December, a time of mental and financial stress and the month when the open enrollment period ended in recent years, is the “worst time of the year to require complex enrollment decisions.”[13] As such, giving people more time to enroll and stretching open enrollment into the early part of each year is likely to boost the number of people covered to a higher level than Georgia’s analysis has accounted for.

Another policy that could bolster enrollment during the year is the recent rule change allowing people with incomes at or below 150 percent of the poverty line to enter the marketplace in any month starting in 2022, rather than needing to have a separate life event to qualify for a special enrollment period (or SEP; this is distinct from the recent six-month, pandemic-related SEP). The enrollment effects could be significant in Georgia, where about 160,000 uninsured adults have incomes between 100 and 150 percent of poverty. This is a new avenue to enroll for people who need coverage but miss the annual open enrollment period.

Build Back Better (BBB),a which is currently being considered in Congress, would extend through 2025 the American Rescue Plan’s premium tax credit enhancements and provide financial help to people with income below the poverty line in states that did not expand Medicaid. If BBB becomes law, Georgia’s 1332 baseline (its estimates of what would happen without the Georgia Access Model) will be even less moored to on-the-ground coverage conditions.

BBB would do many things to bolster enrollment, none of which are included in Georgia’s analysis:

- It would extend the Rescue Plan’s premium tax credit enhancements to 2025, lowering premiums for people with incomes between 100 and 400 percent of the poverty line and allowing people with income over 400 percent of the poverty line to claim the credit;

- It would make people who live in states that did not expand Medicaid newly eligible for a premium tax credit through the marketplace — including 275,000 uninsured Georgians, a plurality of whom, due largely to structural inequities and disparities in coverage rates, are Black;b

- It would dedicate new funding to outreach and enrollment, including in-person assistance, for people formerly in the Medicaid coverage gap;

- It would make employer coverage more affordable for some workers, by allowing them to claim a premium tax credit when premiums cost more than 8.5 percent of income rather than 9.5 percent and by ensuring that people with income below 138 percent of poverty would not be blocked from premium tax credit eligibility due to an employer offer; and

- It would likely lead people to transition from Medicaid to the marketplace, by phasing out the financial incentives for the Medicaid continuous coverage requirement, meaning some people whose income now exceeds Medicaid eligibility levels would be eligible for a premium tax credit in the marketplace.

BBB’s anticipated enrollment gains would need to be factored into the baseline to evaluate whether the waiver meets the statutory guardrails; if Georgia can’t achieve enrollment at least comparable to what would occur without the waiver, its waiver would violate the coverage guardrail. At a minimum, the failure to provide new analysis to account for the effects of BBB would make it impossible for the Departments to calculate the pass-through payments Georgia would receive under the waiver. Operating under an artificially low baseline would generate a higher pass-through payment than the state would otherwise be entitled to receive.

Many people remain unaware of the financial help they can receive to purchase health insurance. This knowledge barrier indicates that more needs to be done to reach people who are eligible. The Georgia waiver would withdraw from federal initiatives to promote coverage — notably marketing and unbiased, in-person assistance — and do nothing to replace them, exacerbating the knowledge barrier and driving down enrollment.

Increased Outreach and Marketing Driving Higher Enrollment

The Biden Administration has made a historic $100 million investment in nationwide marketing to make people aware of affordable coverage in the marketplace during the six-month emergency SEP, in contrast to the Trump Administration’s $10 million in annual funding in prior years.

Marketing is a powerful tool to drive enrollment.[14] In 2016 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) determined that 1.8 million of the marketplace’s 9.6 million enrollees enrolled due to advertising, and by 2017, an estimated 37 percent of enrollments were attributed to advertising.[15] Covered California, a state-run marketplace, found that outreach and marketing reduced premiums for Californians and the federal government by 6 to 8 percent in 2015 and 2016. This is because marketing nudges into coverage healthier people who are less inclined to purchase insurance, lowering the marketplace’s risk profile, which translates into lower premiums and higher enrollment overall.[16] Kentucky’s television advertising was also credited with 40 percent of the unique visitors and web-based applications in Kentucky for plan years 2014 and 2015.[17]

Georgia’s intent to rely on insurer and broker advertising to attract enrollees — instead of federal government advertising driving traffic to one central enrollment platform — is misguided. Research has shown that government advertising is more effective than private advertising. One study found that government advertising was more likely to expand enrollment, with health plan advertising tending to reach only existing customers.[18] Further, cuts to navigator programs did not increase the amount of private-sector advertising.[19]

Pulling out of HealthCare.gov means that Georgia will no longer benefit from this federal investment. Without government-funded advertising, Georgia can expect to have lower enrollment than would occur without the waiver, a factor that the state did not account for in its waiver application.

Enrolling in insurance can be complicated and many uninsured people say they need help to understand their options.[20] Navigators are federally funded, unbiased groups that provide this help to consumers at all stages of the coverage process, from determining eligibility to plan selection to using their coverage. In 2021, HealthCare.gov navigators received a $70 million increase in funding. Georgia navigators saw a $1.8 million increase, with funding rising from $700,000 when the waiver was approved to $2.5 million today.[21]

Unlike the brokers Georgia’s plan relies on, assisters — navigators and unfunded application counselors — are knowledgeable and skilled at reaching underserved populations. They are five times more likely than agents and brokers to report that their clients were previously uninsured, according to a 2016 national survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.[22] Nine in ten assister programs helped eligible individuals enroll in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), compared to fewer than half of brokers. While navigators must perform public education activities on the availability of marketplace coverage and do so in a linguistically and culturally appropriate manner, brokers don’t. Research shows brokers are significantly less likely to perform public education and outreach activities or to help Latino clients, people who have limited English proficiency, or people who lack internet at home. A recent study found that cuts to the navigator program in 2019 led to declines in coverage by people with incomes between 150 and 200 percent of poverty, consumers under age 45, consumers who identified as Hispanic, and consumers who spoke a language other than English at home.[23]

Under its waiver, Georgia would opt out of this federal investment in in-person assistance and would fail to establish any form of impartial, unbiased help, which means that vulnerable uninsured people would be less likely to find coverage, in opposition to the intent of recent 1332 waiver regulations.[24] In fact, the state made it illegal to use state funds on navigators.[25]

President Biden has issued two executive orders that emphasize the Administration’s commitment to continuing federal investment in enrollment, helping the underserved, and ameliorating the effects of structural racism in health coverage rates. They both demand reconsideration of Georgia’s waiver. Executive Order 13985 asks all federal agencies to review new and existing policies to assess whether they advance equity for marginalized and historically underserved communities.[26] Georgia’s waiver doesn’t analyze its impact on equity, which should raise the Departments’ level of scrutiny. The preamble of recent section 1332 regulations emphasizes helping underserved communities and makes clear that a “1332 waiver would be highly unlikely to be approved by the Secretaries if it would reduce coverage for these populations, even if the waiver would provide coverage to a comparable number of residents overall.”[27]

In practice, hard-to-reach and marginalized communities are more likely to become uninsured under the state’s plan due to cuts to in-person assistance, which disproportionately helps people with lower incomes and those who speak a language other than English in the home, as explained above. For example, among the more than 1,500 agents and brokers advertising marketplace services in one Georgia ZIP code, only 47 offer services in Spanish and many fewer in other languages.[28]

Executive Order 14009, on strengthening Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act, calls for an immediate review of all federal agency actions with the goal of making coverage accessible and affordable to everyone.[29] This includes policies that undermine protections for people with pre-existing conditions; waivers that may reduce coverage under Medicaid or the ACA; policies that undermine the marketplace; policies that create unnecessary barriers to families attempting to access ACA coverage; and policies that may reduce the affordability of coverage. Georgia’s waiver violates each of these goals. Agencies are directed to “suspend, revise, or rescind” such prior agency actions, which would include having granted Georgia’s waiver.

Beyond the guardrail violations discussed above, Georgia is in violation of the statutory, regulatory, and procedural requirements of 1332 waivers. In a June 3, 2021 letter, the Departments gave Georgia 30 days to provide updated actuarial and economic analysis to support its assertion that the Georgia Access Model will comply with the statutory guardrails, as well as information about the data and assumptions used in conducting this analysis.[30] The Departments are entitled to this information under authorities in the statute, section 1332 regulations, and Specific Terms and Conditions (STCs) of the waiver to which the state and federal government agreed. But Georgia first expressed confusion about this request[31] and later refused to comply.[32] It claimed the Departments lack authority to request this information or evaluate the waiver post-approval and prior to full implementation, and also that any evaluation was limited to the effects of changes in statute enacted by Congress. These assertions are both wrong.

Georgia claims the waiver terms’ requirement to provide additional information for review applies only after a waiver has been fully implemented, not during the period between approval and implementation. Georgia argues that the STCs are “plainly contemplating monitoring … once a waiver has gone into force,” since there is nothing to evaluate before the waiver is effective. In coming to this conclusion, the state ignores the statute, regulations, and the terms of its waiver approval.

Under the statute, the Departments must create regulations requiring that states submit “periodic reports … concerning the implementation of the program under the waiver” and a “process for periodic evaluation.”[33] The statutory language doesn’t limit when evaluations can be requested. The regulations lay out a robust regime for ongoing monitoring, in language that has stood mostly unchanged since 2012. Under these rules, “following approval” the state must comply with federal law and regulatory changes. The Departments are authorized to “examine compliance” with the terms of the waiver, and states must “fully cooperate” with the Departments in evaluating “any component” of a waiver, including “submit[ting] all requested data and information.” The regulations require the state to comply with all federal policies “following the final decision”— not just following full implementation.[34] Similarly, the STCs provide for “oversight of an approved waiver,” not merely one that has been implemented.[35] They use broad language requiring the state to “fully cooperate” and submit “all requested data.”

The Departments may amend or terminate waivers found to be non-compliant.[36] The STCs themselves reiterate the state’s obligation to provide requested information and the Departments’ authority to conduct oversight[37] and revoke a non-compliant waiver.[38] And both the regulations and STCs authorize the Departments to terminate non-compliant waivers “at any time,” which they couldn’t do if prohibited from collecting information before full implementation.[39]

The ability to collect additional information at any time is also necessary given how section 1332 waivers work in practice. Georgia claims that, pre-implementation, “there is nothing new for a state to report.” But the implementation of a 1332 waiver is an iterative process requiring close coordination and updated analysis along the way. In the normal course of administering a waiver, the Departments must update their analysis based on information from the state to annually calculate pass-through payments, as required by section 1332.[40] This function is infeasible without updated information from the state. In addition, the Georgia Access Model was approved two years in advance. It would defeat Congress’s purposes in creating the statutory guardrails if, during this window of time, a waiver could not be monitored to ensure it remains in compliance.

Changes due to federal statute — namely continued high enrollment even after the Rescue Plan’s enhanced subsidies end in 2022 — merit review of Georgia’s waiver. But even if the new statute didn’t affect the enrollment baseline, other regulations and policies do, and should be considered. Georgia’s refusal letter focuses on STC 7, which authorizes the Departments to re-examine compliance with the guardrails and potentially terminate a waiver based on a change in federal statute. The state contends that federal policy changes, like changes in regulations or increases in federal navigator and outreach funding, can’t trigger an evaluation. Georgia claims that no relevant legislation has been enacted and so STC 7 provides no grounds for review. However, the state ignores another provision, STC 17, which provides for review on much broader grounds. It authorizes the Departments to terminate a waiver “at any time” if the Departments determine that the state has materially failed to comply with the STCs or the statutory guardrails, without restriction. This is reinforced by STC 6, which requires the state to “comply with all applicable federal laws and regulations, unless a law or regulation has been specifically waived.” No federal law or regulation is specifically waived in the STCs.

The regulations include similar language, providing for ongoing review of compliance with the statutory guardrails and reserving the Departments’ right to suspend or terminate a waiver “at any time” if they determine that “a State has materially failed to comply with the terms” of the waiver.[41] In short, the argument for limiting the scope of review focuses on a single ground for review and ignores others that authorize the Departments to look beyond statutory changes in examining a waiver’s ongoing compliance.

In addition to the new reasons for termination, the waiver’s underlying flaws merit reconsideration of whether it complies with the guardrails. Eliminating HealthCare.gov threatens to reduce coverage due to consumer confusion, and many of the people who start their applications on HealthCare.gov but are assessed as eligible for Medicaid would likely hit an enrollment roadblock under the Georgia Access Model, as private insurers and brokers frequently lack the financial incentive to facilitate Medicaid enrollments. Further, reliance on brokers — both web brokers and individual sellers — could result in more people getting coverage that is less comprehensive than they’d otherwise have, since there are strong incentives to lure people into non-compliant coverage. This steering could also raise premiums: healthier people might be pushed to lower-benefit plans, leaving only sicker people in ACA-qualifying plans and driving up their cost.

Georgia claims that privatizing its marketplace would increase enrollment in the individual market by about 28,000 people by giving consumers new options to shop for and enroll in plans.[42] But even if one were to grant Georgia’s unsubstantiated claim that allowing enrollment through insurers and brokers increases coverage, the premise underlying the state’s coverage projection is flawed: the waiver does not add meaningful new enrollment options. Consumers already can enroll in marketplace coverage directly through insurers or brokers — including the web brokers the proposal heavily relies on. At least 17 insurers and web brokers offer these services in Georgia for the 2022 plan year.[43] The waiver itself notes these options are widely available. This means the waiver subtracts pathways to coverage, rather than creating net new pathways.

Meanwhile, the waiver analysis entirely ignores countervailing threats to enrollment posed by dismantling the enrollment and consumer support system that more than half of enrolled Georgians use. Abandoning HealthCare.gov would leave the majority of enrollees without their chosen enrollment platform, almost certainly reducing enrollment significantly.[44] First, fragmenting the health insurance market across brokers and insurers would make insurance-buying less accessible and more confusing for consumers. Second, people who are eligible for Medicaid could have less enrollment assistance. And last, the transition itself would inevitably cause consumers to fall through the cracks, as occurred in states moving between federal and state enrollment platforms, a transition much simpler for consumers than Georgia’s proposed transition from the federal platform to a wholly fragmented enrollment system.

Fragmentation, Loss of HealthCare.gov Would Likely Cause Coverage Losses

Under Georgia’s proposal, enrollment would likely fall because buying insurance would become harder. It’s well documented that having too many choices can stymie consumers.[45] For example, one study of Medicare Part D plans found that having fewer than 15 options raised enrollment, whereas having 15 to 30 options did not, and having more than 30 options actually lowered enrollment.[46] A marketplace consumer in Atlanta has 142 plan options.[47] And consumers who manage to enroll despite being overwhelmed by choice are more likely to delegate their choice to others, regret their selection, and be less confident in the choices they make.[48] Confusion could be even greater under a system that requires consumers to choose among legions of sellers before beginning the process of selecting a specific health plan, with no guarantee of a single platform on which to see and compare all plan choices on equal terms. That same Atlanta consumer has more than 1,500 individual agents and brokers to choose from, with no guarantee that any given broker they choose will sell all available marketplace plans.[49]

HealthCare.gov was created to simplify this complex decision-making process. It allows people to navigate one website to get an unbiased view of all plans eligible for financial assistance and provides tools to compare plans by premium, deductible, out-of-pocket cost, in-network status of preferred providers, and prescription drug coverage, among other features. All plans are guaranteed to meet the ACA’s insurance market standards, like covering the law’s ten essential health benefits and having no lifetime or annual limits on benefits.

Instead of the one-stop shopping experience of the marketplace, Georgia’s waiver proposes a free-for-all run largely by web brokers and insurers. This would rely on a process known as enhanced direct enrollment, under which people apply for marketplace enrollment and select a plan through websites operated by private web brokers and insurers, while eligibility for premium tax credits is determined behind the scenes by the federal government. The waiver says that Georgia will set standards for how web brokers and insurers can display plans based on standards the federal government has set for this process. But these rules leave critical gaps. For instance, insurers show only their own plans, not the full array of plans available through HealthCare.gov. Web brokers are required to show all plans (under federal rules) but can display plans that pay commissions more prominently and show scant information about other plans, even omitting the premium amount. The standards for the online enrollment process, as set by the federal government, don’t extend to individual agents and brokers. And these various entities — web brokers, insurers, and individual brokers and agents — frequently sell plans that fail to meet ACA standards.[50] Indeed, displaying additional categories of options, including coverage that isn’t comprehensive, is a stated goal of the waiver.[51] This would make shopping for health insurance much more complicated — and could lead more consumers to select lower-value coverage without the ACA’s protections, out of confusion rather than true preference.

Failure to successfully build a robust, reliable technology system that helps existing enrollees re-enroll under the new regime could cause consumers to lose coverage or subsidies in 2023, the first year of the new system. But even if the state mostly succeeded in launching the new system, enrollment might fall due to the transition. Georgia predicts losing only about 2 percent of otherwise-returning enrollees due to the change, but other states’ experiences show this figure is unrealistic.[52] Kentucky’s marketplace enrollment fell 13 percent when it transitioned to the federal marketplace in 2017, compared to a 4 percent decline nationally; Nevada’s enrollment fell 7 percent for the 2020 plan year after its transition to a state-based marketplace, compared to flat enrollment nationally.[53] Similar percentage declines in Georgia would translate into a drop of 38,000-71,000 people in marketplace enrollment.

Challenges during transitions away from HealthCare.gov include maintaining communication with existing enrollees, conducting strong outreach to potential new consumers, and transferring account information to facilitate automatic re-enrollment for existing enrollees. Each challenge would likely be especially pronounced in Georgia, which would lack a central system to receive consumer information transferred from HealthCare.gov. While the state claims it would engage in a “robust” transition plan with a “detailed transition strategy,” the waiver provides no details and subsequent reports to the Departments are not publicly available.

Many Georgians Would Likely Lose Medicaid Coverage

HealthCare.gov also facilitates Medicaid enrollment with a “no-wrong-door” application that routes a person to the program for which they’re eligible based on their family size, income, and other factors. In many cases, this prevents someone from needing to complete multiple applications to connect with the correct program. In the open enrollment period for 2021, about 35,000 Georgians who started the process at HealthCare.gov were assessed eligible for Medicaid — more than the number of total enrollees the state projected to gain through the waiver.[54]

Medicaid (including Medicaid managed care organizations) generally doesn’t pay commissions. That means brokers and insurers have no incentive to provide information and assistance to consumers who turn out to be eligible for Medicaid rather than subsidized marketplace coverage, so they might not provide these consumers with any help to enroll. For example, a search on HealthCare.gov displays more than 1,500 agents and brokers that enroll people in individual or family coverage in one Atlanta ZIP code but zero agents and brokers that say they’ll assist with Medicaid or CHIP enrollment.[55]

Brokers and insurers could also steer low-income consumers toward private coverage, including lower-premium, limited-benefit substandard plans, without explaining that they are eligible for comprehensive coverage through Medicaid. Brokers and insurers receive commissions or make a profit as long as a few of these consumers enroll, even if most are deterred by the premiums or out-of-pocket costs and remain uninsured. Consistent with these incentives, some web brokers already neglect to identify certain children as Medicaid eligible. Consider, for example, a parent and child with household income of $15,000, which in Georgia would qualify the child (though not the parent) for Medicaid. The web broker GoHealth fails to identify the child as likely Medicaid eligible, saying explicitly that “you may not qualify for government subsidies” and instead displays a list of full-price marketplace plans that include both the parent and Medicaid-eligible child.[56] Eliminating HealthCare.gov as an unbiased eligibility and enrollment option could significantly decrease enrollment among some of the most vulnerable Georgians.

The waiver estimates premiums would fall 3.6 to 3.7 percent due to the Georgia Access Model.[57] Not only is that estimate based on the flawed premise that the state’s plan will increase enrollment, but it fails to account for the potential for greater enrollment in substandard plans, which could raise premiums for ACA-compliant coverage (and greatly increase consumers’ exposure to catastrophic medical expenses) by pulling healthy people out of comprehensive coverage.

An explicit goal of the waiver is to increase access to coverage that doesn’t meet ACA standards.[58] It envisions an enrollment system that promotes “the full range of health plans licensed and in good standing” in the state, including short-term, fixed indemnity, accident, and single-disease plans, which normally can’t be sold alongside ACA plans through enhanced direct enrollment. Short-term plans, in particular, pose a considerable risk to consumers but have grown in popularity, especially in Georgia, since the Trump Administration expanded them in 2018.[59] One review of the most popular short-term plan in Atlanta found that although it had lower premiums, its deductible and maximum out-of-pocket costs were more than 2.5 times higher than the most popular bronze ACA plan, and it offered no coverage of prescription drugs, mental health services, or maternity care.[60]

Brokers have an incentive to steer consumers toward short-term plans because they tend to pay higher commissions — the waiver notes that brokers selling short-term coverage receive average commissions that are up to 22 percent higher than those for ACA-compliant plans.[61] Insurers also profit on short-term plans, which aren’t required to meet the medical loss ratio standards for ACA-compliant plans: short-term plans spent only about 53 percent of premium revenue on medical care, compared to at least 80 percent for ACA plans.[62]

Experience with enhanced direct enrollment programs shows that these incentives sometimes give rise to “steering,” in which web brokers screen applicants before sending them down the official enrollment pathway and divert some toward substandard plans that pay higher commissions but leave enrollees exposed to catastrophic costs if they get sick.[63] For example, some web brokers collect information that is useful in the medically underwritten market (such as height and weight) and feed the information to a broker call center, where the web broker rules prohibiting certain types of steering appear not to apply.[64] Consumers visiting web broker sites often must agree to telephone solicitation by the web broker, insurance agents, insurance companies, and partner companies, making them ripe for pressure tactics in the future. In addition to the data the consumer voluntarily submits, other information, like browser tracking data, could be gathered and sold. Based on these data, a consumer may see targeted advertisements for alternative non-ACA plans or receive phone solicitations now and in the future, including during the next open enrollment period.

Even under current law, 1 in 4 marketplace enrollees that sought help from a broker or insurer said they were offered a non-ACA-compliant policy as an alternative to marketplace coverage.[65] And consumers are often subjected to aggressive or even fraudulent marketing tactics.[66] One study, for example, showed that most brokers gave ambiguous, misleading, or demonstrably false information regarding short-term plan coverage for COVID-19-related illnesses.[67] In another recent secret shopper study, brokers recommended short-term and other non-ACA coverage in 75 percent of the marketing calls versus marketplace plans.[68] Georgia’s proposal would create many new opportunities for deceptive and aggressive marketing.

Healthier people would be more likely to opt for short-term plans, since less healthy people are less likely to qualify for a policy, face higher premiums when they do, and might be more apt to recognize absent benefits and other limitations. If healthier consumers exited the ACA-compliant market, its risk pool would become less healthy, on average, driving up premiums; in states that took advantage of the Administration’s expansion of short-term plans — like Georgia, which has few restrictions — premiums for comprehensive coverage went up by about 4 percent.[69] The waiver doesn’t account for short-term plan enrollment, its impact on ACA-compliant coverage enrollment, the risk profiles of enrollees in short-term or ACA-compliant plans, or the likelihood of premium increases in the ACA-compliant market.

Then and Now, Waiver Fails Federal Tests for Approval

The Georgia Access Model fails the statutory tests for 1332 waivers. Both prior to approval and even more so now, it does not meet the requirements that waivers cover as many people, with coverage as affordable and comprehensive as would have been covered without the waiver.[70]

Coverage. Georgia’s waiver baseline doesn’t reflect the increased enrollment due to laws, regulations, and policies that have been put into place since the waiver was approved. Therefore, Georgia fails to show that its plan can achieve coverage numbers that are comparable to the enrollment otherwise expected without the waiver. In fact, the plan would likely decrease enrollment. Georgia’s claim that the waiver would increase enrollment rests on the flawed premise that it would introduce a new enrollment option; in reality, it would eliminate the option to compare plans and enroll in coverage through a neutral platform. In addition, as discussed above, privatizing the marketplace would make it more difficult for some consumers to enroll in coverage. Transitioning existing enrollees from HealthCare.gov to the new system could lead to additional coverage losses, and there would be no coordinated plan to get new enrollees. In all, the expected effect of the waiver is to reduce coverage, failing the statutory test.

Affordability. The Georgia Access Model would likely increase premiums for comprehensive coverage. That’s partly because it is very unlikely to increase marketplace enrollment, an assumption on which its projected 3.4 percent premium reduction is based. In addition, driving more healthy consumers to less comprehensive underwritten plans would likely increase marketplace premiums through adverse selection, something Georgia’s actuarial analysis doesn’t account for. And given the waiver’s reliance on incentives for agents and brokers in the private market, commissions would likely increase, further raising premiums. The state’s flawed, incomplete actuarial analysis makes it impossible to know whether the affordability guardrail can be met, on balance.

Comprehensiveness. Georgia’s privatization proposal creates new opportunities for brokers and insurers to steer healthy people toward substandard plans that do not meet ACA requirements. Thus, it would likely result in more Georgians enrolled in non-comprehensive plans that expose them to catastrophic costs if they get sick.