The Affordable Care Act (ACA) established health insurance marketplaces to serve as a single place where consumers could compare health plans based on price and quality and apply for financial assistance. All marketplace plans meet a consistent set of standards: they cover a core set of benefits, can’t set premiums based on health status or gender, and are displayed in an impartial way to simplify consumer decision-making. Consumers can submit a single application at the marketplace website to connect with the type of health coverage they’re eligible for, whether Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), or a private plan.

But today, many people use websites other than the marketplaces to enroll in marketplace plans and apply for ACA subsidies. Through a federally created pathway called “direct enrollment” (DE), insurance companies and brokers (including web-based brokers) use their own websites to help people enroll in marketplace plans and access subsidies. And in late 2018, the federal government began approving entities to use the “enhanced direct enrollment” (EDE) pathway, which allows insurers and brokers to handle the entire application process, eliminating all direct contact between the consumer and the marketplace.

Direct enrollment raises several concerns, primarily because DE entities lack the benefits and protections that the ACA marketplaces provide. Among the concerns:

-

Many DE entities offer plans that don’t comply with ACA standards, and they may benefit financially if they enroll more people in them. Some insurers and brokers operating through DE offer short-term health plans and other types of plans that don’t meet ACA consumer protections and benefit standards but pay high commissions to agents and brokers. Federal rules bar DE entities from displaying these plans alongside marketplace plans, but some DE sites use screening tools to shift consumers away from marketplace options. This raises a serious threat to both consumers and the ACA marketplace if insurers and brokers use their status as approved DE entities to enroll consumers in non-compliant plans. Also, the sites’ screening tools collect personal and health information that can be used for future marketing of non-compliant plans.

For example, one web broker’s listing of “Health Insurance” options often shows only non-ACA plans; the site lists ACA-compliant plans under “Obamacare Coverage.”[1]

-

People who are eligible for Medicaid or other programs may face additional barriers to enrolling when they rely on a DE website. The marketplace has a “no wrong door” policy, meaning that consumers who go to the marketplace website can fill out one application and be routed to Medicaid, CHIP, or marketplace subsidies based on the information they provide. But some DE websites divert consumers from the marketplace application process before they even reach it, by not informing them that they might be eligible for no-cost coverage or by steering them toward non-ACA products.

One health insurance issuer encourages consumers with Medicaid-eligible children

to “buy a plan direct” from them, which bypasses the marketplace’s single streamlined application that would indicate their child’s Medicaid eligibility.

-

DE websites prevent consumers from fully comparing private health plans based on price and quality, which impedes competition among insurers. Unlike marketplace websites, which allow people to compare all qualified health plans on an apples-to-apples basis, DE entity websites may not present all available marketplace plans or comparable plan information. Moreover, DE entities may have financial incentives to steer consumers to certain insurers. Consumers thus may not end up with the plan that would best meet their needs. Moreover, insurers with significant market share can use DE and EDE to maintain their dominance, making it harder for small insurers or new entrants to compete.

One web broker lists what appears to be a complete list of plans (“17 of 17”) available in a rating area but in reality covers only about one-third of the available plans.

Not all DE entities have all these problems, but the DE program lacks safeguards to protect consumers from harm. And despite evidence that DE already poses risks to consumers, a recent Trump Administration proposal would expand DE further by allowing application assisters and navigators to enroll consumers using a DE pathway instead of the marketplace. These changes are consistent with the Administration’s larger effort to privatize more marketplace functions and reduce the resources, public presence, and capacity of the marketplaces themselves.

The ACA created health insurance exchanges, now often called marketplaces, that are operated by the federal government or a state. It requires them to perform a number of functions, including certifying qualified health plans (QHPs) that meet all ACA standards, providing a website where consumers can compare QHPs, offering tools such as an online calculator to help people understand their cost for coverage, operating a telephone call center, and establishing a navigator program to provide consumers with impartial help.[2] Marketplaces can only offer QHPs, not other plans that fail to meet ACA standards. They are the only entities that can determine eligibility for ACA subsidies available to people enrolled in a QHP. Also, under the ACA’s “no wrong door” policy, the marketplaces can connect Medicaid- or CHIP-eligible people with those programs. The marketplaces (HealthCare.gov and the state-specific marketplaces for states that don’t use HealthCare.gov[3]) are a single place for consumers to get impartial information about and enroll in coverage that meets the ACA’s standards and their own health needs.

From the beginning of the marketplaces, agents and brokers (including web brokers) and insurance companies have helped people enroll in marketplace plans and apply for subsidies. Under the ACA, a state may permit agents and brokers to “enroll individuals and employers in any qualified health plans in the individual or small group market … through an Exchange” and “assist individuals in applying for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions for plans sold through an Exchange.”[4] Brokers must comply with federal regulations that outline their obligations in enrolling qualified individuals and helping them apply for financial assistance, including registering with the marketplace, complying with state licensure standards, receiving training, and complying with privacy and security standards.

Under direct enrollment, a consumer typically visits a DE entity’s website and is screened for eligibility for financial assistance. (If the consumer is working with an agent or broker that uses a DE site, the broker provides the information on the consumer’s behalf.) If the consumer is likely eligible for marketplace subsidies based on the initial screening and wishes to proceed, she is electronically handed off to the marketplace to complete the official application and receive the official eligibility determination; she then returns to the DE portal to select a plan and enroll. (In some web portals, consumers select a plan after the initial screening but before completing the official application at HealthCare.gov.) Brokers say this transfer from the DE portal to the marketplace and back again, sometimes called a “double redirect,” is cumbersome and frustrates consumers, causing many to discontinue the application.

To address these and other concerns, the federal Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight unveiled enhanced direct enrollment beginning in the 2019 plan year.[5] The EDE option allows certified entities to collect all application information through their websites, submit the application to the marketplace, and then retrieve the marketplace’s official eligibility determination; the consumer never interfaces with HealthCare.gov. The EDE entity can also help consumers with post-enrollment issues, such as responding to notices and submitting documents to verify eligibility without going to the marketplace website. EDE’s stated goals are to give consumers more ways to shop for coverage, encourage them to complete the application process, and incentivize brokers to keep clients connected to marketplace coverage.

Dozens of entities are approved to conduct direct enrollment, and nine are approved to conduct EDE.[6] Use of direct enrollment has grown: agents and brokers facilitated 42 percent of HealthCare.gov enrollments for the 2018 plan year, and 39 percent of those enrollments came through direct enrollment.[7]

Concerns About Direct Enrollment and Enhanced Direct Enrollment

While offering multiple avenues to enroll in marketplace coverage has certain benefits, DE and EDE lack the protections the ACA marketplace provide, exposing consumers to various risks.

The marketplace’s qualified health plans must follow the ACA’s individual market rules. They cover comprehensive benefits and can’t deny coverage or charge higher prices to people with pre-existing conditions. A few DE entities exclusively sell qualified health plans, but most also sell other health products such as short-term health plans, fixed-indemnity plans, and health care sharing ministries.[8] Such non-ACA plans often are not in the consumer’s best interest. They can reject or charge higher premiums to people with pre-existing conditions; charge more based on age, gender, or any other factor; impose lifetime and annual benefit limits; require cost-sharing of any amount; and leave out ACA essential health benefits. For example, Kaiser Family Foundation research found that no short-term plans offered through two major web brokers covered maternity care and fewer than one-third covered prescription drugs.[9]

In addition, the average short-term plan in 2017 spent less than 65 percent of premium dollars on medical care, with the remainder going to profits and overhead, compared to at least 80 percent for ACA-compliant individual market policies, according to research from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The three largest insurers offering short-term coverage spent even less on medical care: 44, 34, and 52 percent.[10]

Despite their serious drawbacks for consumers, non-ACA plans tend to pay high commissions to agents and brokers, including web brokers.[11] Short-term plans pay commissions of close to 20 percent, compared to 5 percent for a typical ACA-compliant plan, according to eHealth.[12] Commissions in the marketplace have declined, and many QHPs pay no commissions at all.[13]

Direct enrollment entities can use their websites to steer enrollees into these higher-commission products. For example, the navigation drop-down menu on eHealth’s landing page (www.ehealthinsurance.com/) offers “Health Insurance” as the default; selecting “Health Insurance” will typically display short-term and fixed-indemnity plans and bypass qualified health plans altogether in most cases.

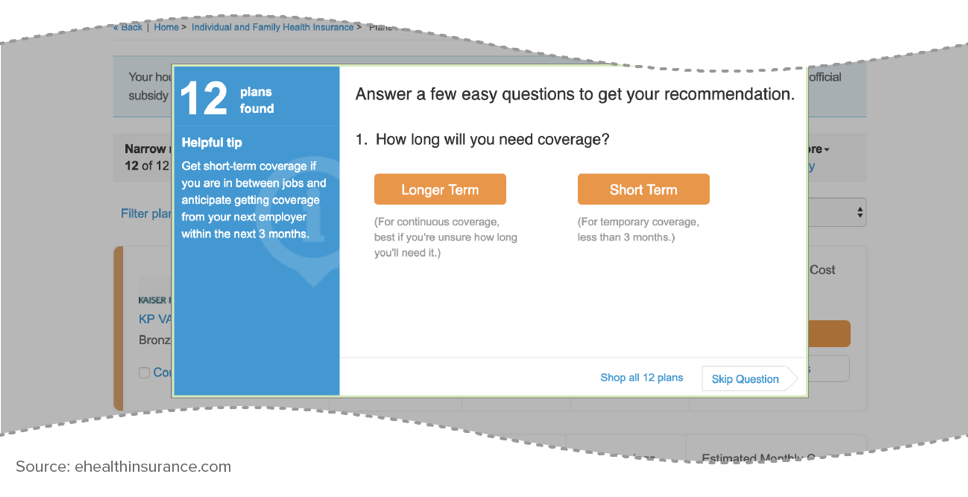

If the consumer instead selects “Obamacare Coverage” (the fifth of the eight product options), only QHPs are displayed. This is consistent with federal regulations: a DE entity must display QHPs on a separate page from non-QHP products, and once the consumer begins QHP plan selection, non-QHP plans or non-QHP ancillary products (like vision or accident coverage) can’t be marketed until the consumer concludes plan selection.[14] However, even on eHealth’s QHP selection page, diversions are still possible. For example, a chat box automatically opens, where a company representative can answer questions on ACA-compliant coverage but may also recommend a short-term or indemnity plan. Separately, clicking the “Get Recommendations” link on the page generates a pop-up box asking whether the consumer needs longer- or short-term coverage (see Figure 1); consumers who select short-term coverage and indicate no pre-existing medical conditions are directed to short-term plans, while people with health conditions are directed back to the marketplace plan selection page. This dynamic raises marketplace premiums over time by luring healthier people away from the individual market and into short-term plans, leaving a costlier group behind.[15]

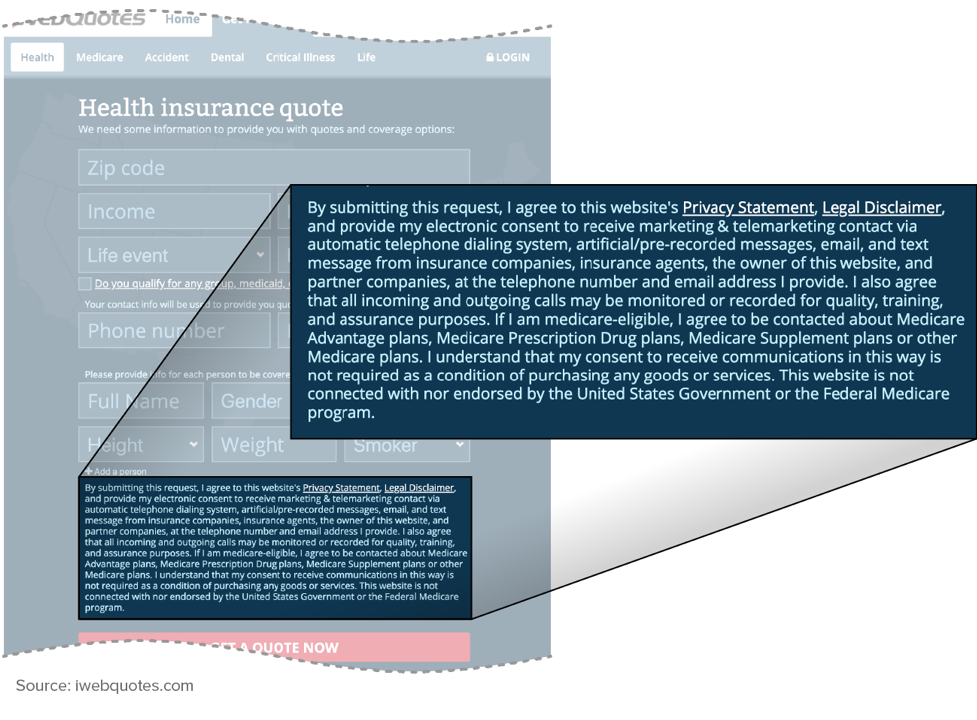

Some screening tools on DE web brokers’ sites gather information that is irrelevant to enrollment in a QHP, potentially to determine whether to target them for a non-ACA plan based on their health status or other characteristics. DE web brokers often have a screening tool on their landing page that gathers information that can factor into the cost of marketplace coverage, such as age, family composition, income, and tobacco use. But in some cases, the broker also asks about health conditions, prescription drugs, height and weight, gender, or other factors that could be used for underwriting purposes to enroll a person in non-ACA coverage. Several DE entities are lead-generating websites that pass this information to brokers for phone solicitations, where there is no firewall between the sale of QHPs and non-ACA plans. Brokers can use aggressive marketing tactics, encouraging consumers to enroll in a short-term plan while giving them only the barest information about it.[16]

Consumer information can also be used beyond the initial insurance inquiry. The web broker iWebQuotes collects name, phone, and address information, along with health conditions, gender, height, and weight. To receive a plan quote, the consumer must agree to a disclaimer and consent “to receive marketing & telemarketing contact via automatic telephone dialing system, artificial/pre-recorded messages, email, and text message from insurance companies, insurance agents, the owner of this website, and partner companies.” (See Figure 2.)

In addition to the data the consumer enters on the web form, other information, like browser tracking data, is presumably gathered and sold. This could include: the websites consumers visit, for how long, and in what sequence; search queries; purchases; device information; location; when, where, and how many times they’ve seen previous advertisements; and what links they click on. Based on this data, a consumer may see targeted advertisements for alternative plans or receive phone solicitations now and in the future, including during the next open enrollment period.

The cumulative impact of allowing or even encouraging consumers to buy underwritten and substandard plans via DE entities ultimately could harm the stability of the marketplaces and their enrollees. If healthier people enroll in substandard coverage, the population left in marketplace coverage will be sicker, on average, which could raise QHP premiums and destabilize the market.

The ACA’s “no wrong door” policy enables consumers seeking coverage at the marketplace to complete a single, streamlined application to determine eligibility for and enroll in Medicaid, CHIP, or marketplace coverage. Consumers don’t need to navigate multiple agencies and systems to secure the coverage each family member is eligible for. DE, however, can interfere with the “no wrong door” policy by failing to notify very low-income adults that they or their children may be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP and instead trying to sell them private plans. The likely outcome is to discourage consumers from beginning the single, streamlined application, causing some people to enroll in less comprehensive, less affordable private plans or to remain uninsured.

Many web brokers ignore consumers’ potential Medicaid eligibility altogether unless at least one household member is eligible for subsidized marketplace coverage. For example:

- Presented with a family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with a $15,000 household income (91 percent of the federal poverty line for 2019 coverage), Value Penguin (www.ValuePenguin.com) displays high-deductible, unsubsidized plans starting at $424 per month, with no indication that both the 31-year-old parent and 6-year-old child are likely eligible for Medicaid. The same family in Huntsville, Alabama, sees plans starting at $552 for coverage that includes the child, who is likely eligible for Medicaid. (Because Alabama has not expanded Medicaid, the parent is in the Medicaid coverage gap, with an income too high for Medicaid but too low to qualify for the ACA’s premium tax credit.)

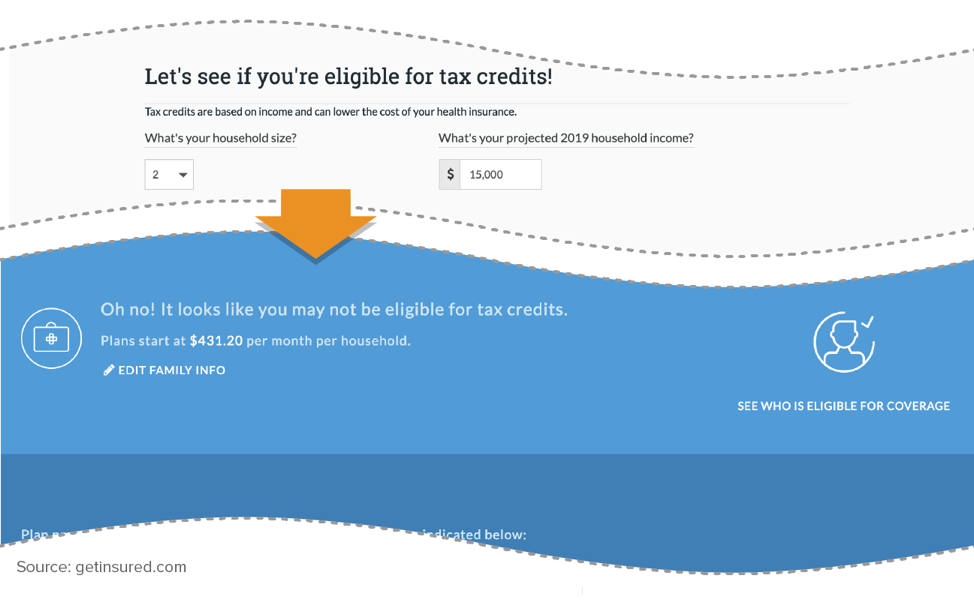

- Get Insured (www.GetInsured.com) correctly identifies a Houston child as Medicaid eligible when her parent is screened as eligible for a premium tax credit at household income of $20,000 (122 percent of the federal poverty line for 2019 coverage). However, if the same parent is in the Medicaid coverage gap, with household income of $15,000, the site doesn’t note the child’s likely eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP. Instead, it tells the consumer, “Oh no! It looks like you may not be eligible for tax credits,” and displays full-cost plans with a premium that includes both parent and child, starting at $431 per month. (See Figure 3.)

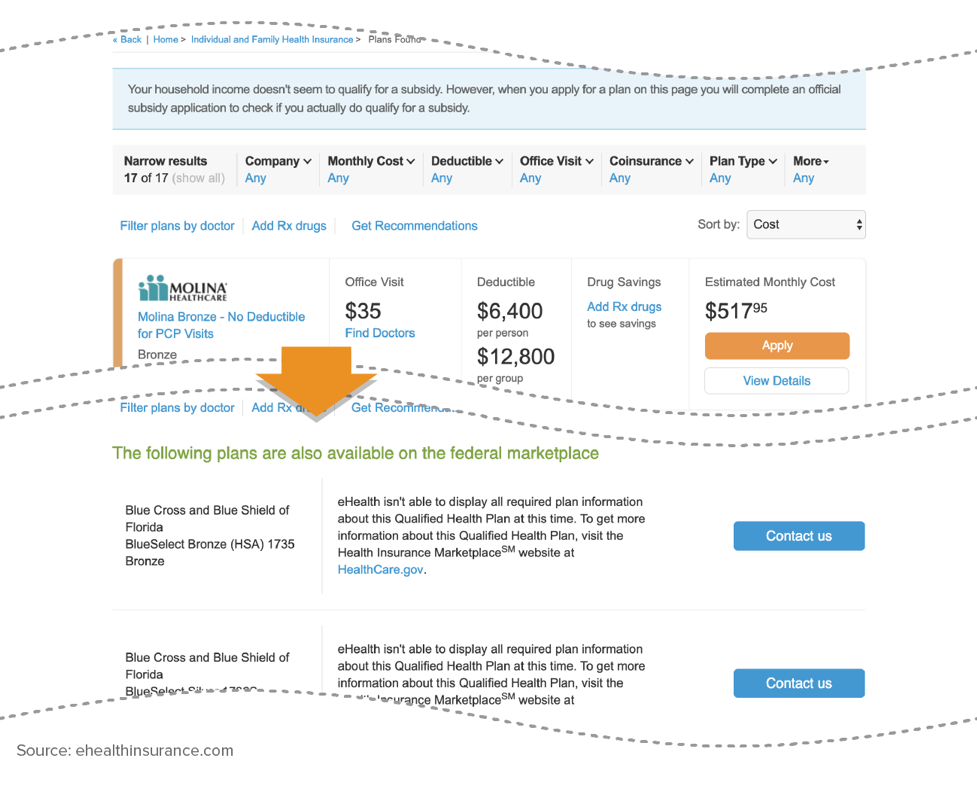

- Similarly, eHealth shows a Virginia family with income of $15,000 an array of unsubsidized plans along with this message: “Your household income doesn’t seem to qualify for a subsidy. However, when you apply for a plan on this page you will complete an official subsidy application to check if you actually do qualify for a subsidy.” It doesn’t mention that both the parent and child are eligible for Medicaid in Virginia, an expansion state. The site displays the same message for the same family in Oklahoma, where the parent is in the coverage gap but the child is Medicaid eligible.

At these web broker sites, with no indication that a household member likely qualifies for Medicaid, no link to HealthCare.gov or the state Medicaid agency, and a prohibitively high unsubsidized premium, a low-income parent is unlikely to begin applying.

As noted, once a consumer enters a QHP selection pathway, non-QHPs cannot be marketed until the consumer exits the QHP selection page; but no similar prohibition applies to marketing to Medicaid-eligible consumers. For example, after correctly identifying a consumer as likely eligible for Medicaid through its screening process, eHealth suggests that he purchase a short-term, limited-duration or telemedicine policy “while you wait for a decision from your state’s Medicaid authority.” Consumers who apply for a short-term plan — or even visit that page of the website — would likely receive a significant marketing push for those plans, whether or not they later enrolled in Medicaid.

In other cases, web brokers use sleight of hand to move Medicaid-eligible consumers into other types of plans. Florida Blue (www.FloridaBlue.com) tells a family that is not eligible for a tax credit (because the parent is in the coverage gap and the child is Medicaid eligible), “This means you can buy a plan direct from Florida Blue.” Even though the site flags the child as eligible for Medicaid, it provides no link to HealthCare.gov or the state’s Medicaid agency to apply for Medicaid. Instead, it displays a menu of unsubsidized plans and automatically includes the Medicaid-eligible child in the premium if a consumer selects a plan.

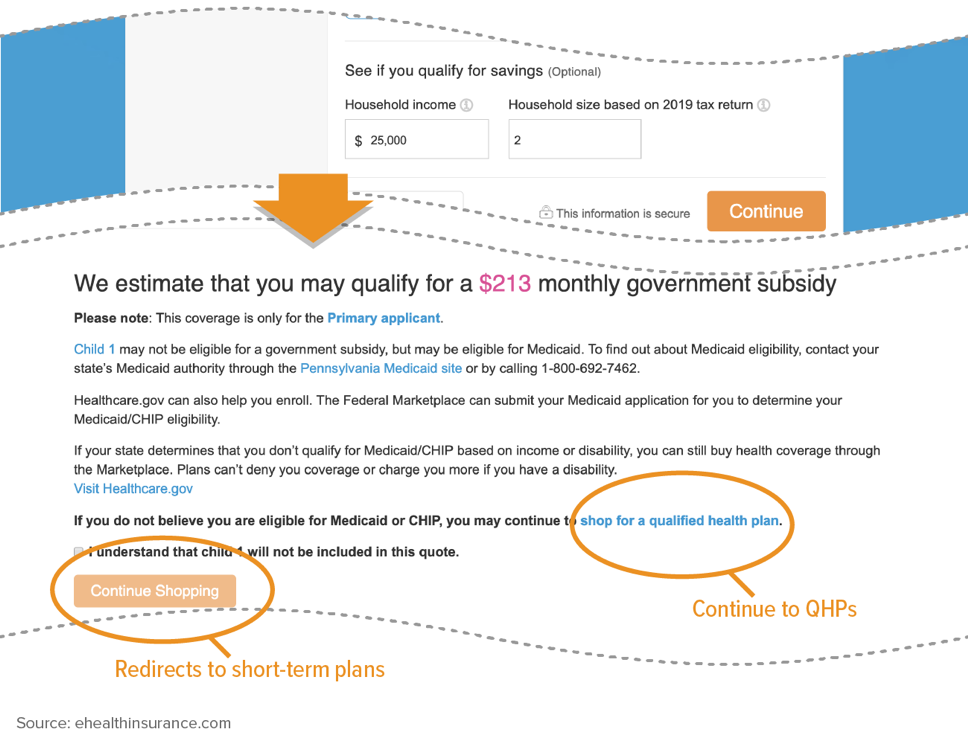

In another example of misdirection, eHealth’s “Health Insurance” screening tool correctly identifies a subsidy-eligible consumer with a Medicaid-eligible child. But if the consumer checks a box to confirm that the Medicaid-eligible child should not be included in the price quote and hits “Continue Shopping” directly beneath the box, she is quickly diverted to non-compliant plans. (See Figure 4.)

In short, in sharp contrast to the marketplace’s “no wrong door” approach, some web brokers have many wrong doors. Consumers could easily be confused about the different types of plans and their eligibility for Medicaid or subsidies. Misdirection could be even more consequential when consumers use EDE and are not brought back to HealthCare.gov to complete their application and eligibility determination.

The marketplace is a one-stop shop for health plan enrollment. Consumers can go to one website to see every marketplace plan available to them, along with premium and cost-sharing information, the discounts available through premium and cost-sharing subsidies, provider directories, and other comparative information. Any carrier that meets the standards can have its plans displayed, even if it has a small advertising budget or market share.

DE is supposed to simplify the consumer shopping experience but instead makes it harder; consumers don’t know which online brokers are registered to sell marketplace plans or whether a given broker displays all or only some of the available plans, and they (unknowingly) will see different plan options depending on which web broker or issuer they choose. For the 2019 plan year, for example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) didn’t make a directory of approved DE issuers and web brokers public until December 13, two days before open enrollment ended.[17] Even then, the directory acknowledges that “[n]ot all approved partners have provided CMS with information to display here.”[18] For example, eHealth isn’t listed, even though it sold marketplace plans and its U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filing indicates that it is a direct enrollment entity.[19]

Even at an approved DE entity, comparing plans can prove difficult. Insurers that are approved to use DE display only their own products and exclude other marketplace offerings entirely, with a disclaimer directing shoppers to HealthCare.gov for the full list of plans. Web brokers are technically required to display all plans, but the plan information they must show is minimal — only the QHP issuer’s contact information, the plan name, type, metal tier, and state. Brokers do not have to display premiums and deductibles or a host of other information consumers need, as long as a standardized disclaimer directs consumers to HealthCare.gov for more information.

Federal rules also give web brokers plenty of leeway to show certain plans (such as those that pay commissions) more prominently. It’s permissible, for example, for a web broker to display plans that pay commissions with full-color logos and premium and cost-sharing information, while simply listing other carriers’ plans in plain text at the bottom of the page. In another example, beside each plan eHealth is required to list but doesn’t earn a commission selling, a button encourages the consumer to call an eHealth agent. A consumer may expect to get more information about the plan if they call, but since those plans don’t pay a commission, an agent won’t have any plan details, not even the premium, and can instead press the consumer to enroll in commission-paying QHPs and non-compliant plans, without being constrained by the bright-line marketing restrictions on plan display. Web brokers can also let the compensation they receive from plans determine the plan recommendations they make to consumers.[20]

Consumers are likely to be confused by their plan options. For Duval County, Florida, for example, eHealth displays what it calls “17 of 17 plans.” (See Figure 5.) Consumers may assume this is a complete list of their options, but listed in plain text at the bottom of the screen are 32 additional plans from Florida Blue, all without the premium or cost-sharing information needed to make a meaningful comparison. The same consumer could go to Florida Blue’s website and find pricing for those plans, 15 of which are cheaper than the lowest-cost plan on eHealth but not even a plain-text listing of the competing plans. A trip to Health Sherpa (www.healthsherpa.com) would list all 49 plans, as HealthCare.gov does. Without visiting multiple websites, consumers would have difficulty finding and comparing their plan options; they won’t know what financial considerations drive web brokers to preference some plans over others, and some could mistakenly assume the distinctions reflect the plans’ relative quality. This is the type of fractured shopping experience the marketplace is designed to remedy.

Reverting to the disjointed shopping experience consumers had prior to the ACA also limits the marketplace’s ability to lift up smaller or newer health plans. One significant barrier to market entry, even for established insurers entering a new state, is the name recognition and pricing influence of the dominant insurer. Receiving equal treatment in the marketplace can help new insurers gain their footing without substantial up-front marketing and commission spending. Direct enrollment foils this in two ways. First, an insurer may need to pay substantial commissions to brokers to appear on web broker platforms and compete with the dominant plan. Second, a dominant insurer can become a direct enrollment entity itself and drive enrollees directly to its own platform instead of the marketplace — initially and in plan renewals — so potential enrollees never even see other QHP options.

Enhanced direct enrollment could have an even more anti-competitive result than DE. Not only will a bevy of web brokers highlight only their preferred plans, but since consumers aren’t directed to HealthCare.gov at any point, they are less likely to see the full array of available plans.

Direct enrollment puts barriers between the consumer and the marketplace by delegating the plan shopping experience to private (and self-interested) entities. Enhanced direct enrollment goes further, fully erasing HealthCare.gov from the consumer’s experience. The increased privatization of marketplace functions has serious consequences for consumers and the marketplace.

The marketplace is a single-stop platform designed to serve every consumer and demystify shopping for health plans, particularly for low- and moderate-income consumers, many of whom have never shopped for private coverage. It has developed tools, such as help text and glossaries, that have undergone extensive public input, and it meets certain federal requirements to assist people with limited English proficiency and people with disabilities.

Privatizing core marketplace functions through direct enrollment makes shopping considerably harder for consumers who want comprehensive information to compare all their plan options. While one justification for DE is the innovation that private web brokers could bring to the shopping experience, most brokers don’t compare with the marketplace’s robust tools, which enable consumers to sort plans according to anticipated yearly cost, search provider directories, check coverage of prescriptions, and easily navigate to full plan information. A consumer visiting DE entity websites might have to shift among several sites to get a complete menu of the available plans or to eventually apply for Medicaid. EDE’s elimination of the “double redirect” may smooth out one part of the consumer shopping experience, but direct enrollment’s fundamental flaws greatly complicate the tasks of comparing plans and making a selection. Privatization of marketplace functions also encourages insurers to compete on web broker sites on the basis of commission and advertising money instead of objective plan features — something the marketplace was designed to remedy.

Some have suggested expanding the use of private direct enrollment pathways and replacing the marketplace altogether.[21] The Trump Administration is moving in that direction. It has cut marketplace outreach funding by 90 percent since 2016 and navigator funding by more than 80 percent; and the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) navigator funding awards now favor entities that are willing to recommend short-term plans and other non-ACA plans to consumers.

While scaling back impartial assistance, the Administration is actively promoting the use of agents and brokers. In the third week of open enrollment, HealthCare.gov’s “Apply for Health Insurance” page was altered to promote the option of using an agent or broker over other methods, such as enrolling directly or with the help of an assister.[22] In another example, HHS’s proposed payment parameters rule for 2020 encouraged navigators to “evolve” and would have newly allowed them to enroll consumers through web brokers instead of the marketplace.[23] It also would further reduce funding available to support navigators and other marketplace operations by reducing the user fees paid by health plans. Reducing funding and outsourcing core marketplace functions could compromise in-house expertise, even as the marketplace will be asked to serve the consumers with the most complex situations, whom most direct enrollment entities can’t or won’t help.

Direct enrollment often harms, not helps, consumers. It could raise marketplace premiums by undercutting the ACA’s market reforms if the consumers with the most favorable health profiles are cherry-picked from among marketplace enrollees. Consumers can be misled into enrolling in substandard plans or not enrolling at all, even if they are eligible for Medicaid or subsidized comprehensive insurance, and can be confused by private websites that purport to offer marketplace coverage but do so selectively and subject to their own financial considerations.