One of the most important steps Congress can take to advance health equity in recovery legislation under consideration is to close the Medicaid “coverage gap.” More than 2 million adults, majorities of whom live in the South and are people of color, are uninsured and in the coverage gap, meaning they have incomes below the federal poverty line but no pathway to affordable coverage because their state is one of 12 that has refused to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion. Budget reconciliation legislation passed by the House Energy and Commerce Committee would permanently close the Medicaid coverage gap, and Congress should ensure this solution remains permanent and comprehensive in the final recovery package.

People of color make up about 60 percent of those in the coverage gap, higher than their 41 percent share of the adult, non-elderly population in non-expansion states. This reflects economic, educational, and housing injustices that lead to higher rates of poverty for people of color and over-representation in low-paid jobs that don’t offer employer coverage. Moreover, many of the states that have refused to adopt the expansion have a long history of policy decisions, based on racist views of who deserves to get health services, that restricted access to coverage in the past and continue to do so today.

Closing the coverage gap is an important step in undoing the effects of structural racism that continue to affect people’s health and well-being. A large body of evidence suggests that closing the gap would:

- Help the people in the coverage gap afford and access health care. States that expanded Medicaid eligibility to more low-income adults showed a greater reduction in racial disparities in coverage and access to care, narrowing gaps in uninsurance rates between Black and Latino people and white people and decreasing racial disparities in screening rates for certain conditions and ability to afford care.

- Improve outcomes for key conditions that have a greater impact on communities of color. Expanding Medicaid helped reduce disparities in certain chronic illnesses, improve maternal health outcomes for Black mothers, and remove barriers people of color face in accessing behavioral health care.

- Bring increased financial security and protection from medical debt, which affects people of color at a higher rate. Medicaid expansion states had smaller differences between communities of color and white communities in the share of medical debt than non-expansion states.

- Improve stability of health systems that people of color rely on, including rural hospitals, safety net hospitals, and community health centers, which would see a reduction in uncompensated care. Rural hospitals that have closed in several non-expansion states like Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina were more likely to be located in counties with shares of Black residents above the statewide average.

Closing the coverage gap is only one step toward health equity, where everyone has a fair opportunity to achieve the best health possible. Additional work is needed to address critical health equity challenges, such as improving the cultural competency and diversity among the health care workforce, reducing bias among health providers, and responding to social factors such as food insecurity and housing instability that disproportionately affect marginalized racial and ethnic groups because of historic and ongoing racism and discrimination. But closing the coverage gap is an important component to achieving health equity. It would provide more than 2 million people health coverage so they can access needed health care services and receive critical care coordination services that can be vital to managing illnesses.[1]

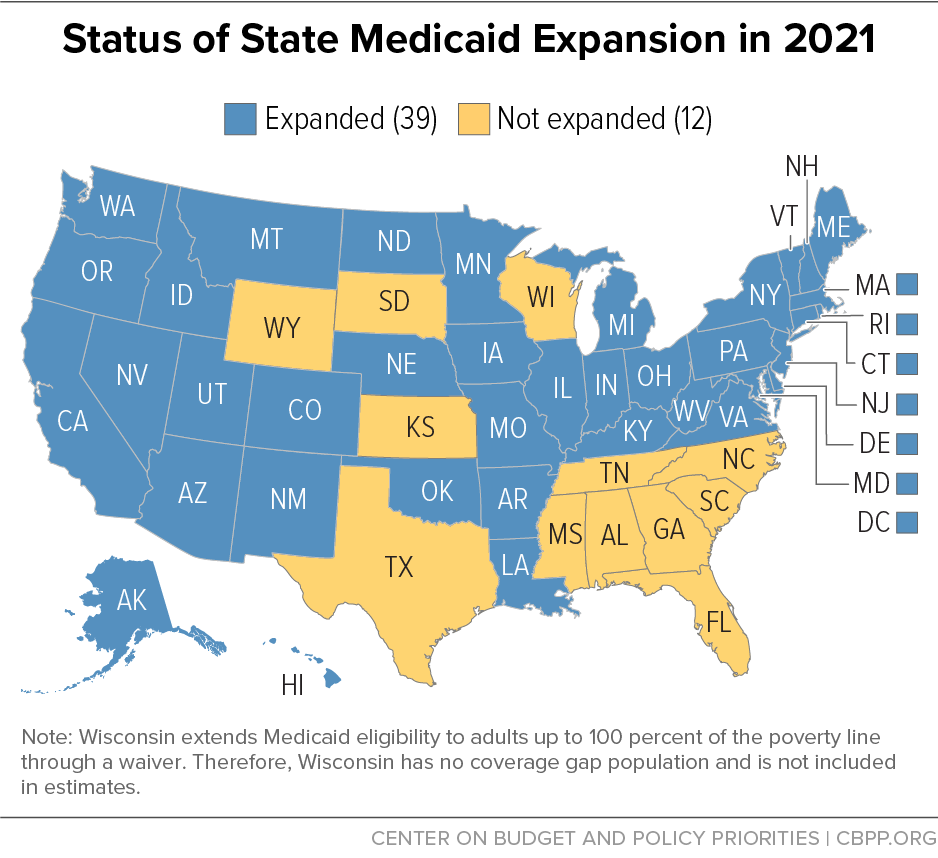

Most of the states that have refused to adopt the Medicaid expansion — despite strong financial incentives for the states and clear health and economic benefits for individuals — are located in the South and have above-average shares of Black and brown residents. (See Figure 1.) Many of the same states choosing not to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income adults also have a long history of restricting access to health care to low-income people in their states.

Before Medicaid’s enactment in 1965, states could opt into federal programs to pay for health care for low-income people. But many states in the South with larger Black populations opted not to participate; only 3.3 percent of program participants in 1963 came from Southern states.[2]

Once Medicaid was established, states continued to have flexibility to make certain decisions related to the breadth of the program and these states often made choices that restricted access. For example, Medicaid eligibility for children and parents was originally linked to eligibility for cash assistance through the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program. States in the South typically had very limited AFDC programs and historically denied Black and brown people access to aid through very restrictive eligibility rules and other discriminatory practices.[3] Prior to the mid-1980s, the only way most parents and children could receive Medicaid was to receive assistance through AFDC; these restrictive policies meant that access to health coverage was also very limited. After Medicaid eligibility expanded for children starting in the mid-1980s, the eligibility restrictions in AFDC had less impact on children but continued to sharply limit Medicaid access for parents.

In 1996, when the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program replaced AFDC, Medicaid eligibility was delinked from eligibility for cash assistance. In response to this “delinking,” some states chose to expand Medicaid eligibility to cover more parents (child eligibility was already being expanded through other mechanisms), but others, including many states that later refused to expand Medicaid, maintained low eligibility levels for parents that dated back to their old AFDC programs.

The ACA called for expanding Medicaid to all non-elderly adults, parents and non-parents alike, with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. In states that refuse to adopt the expansion, adults without minor children at home continue to have no pathway to coverage if their incomes are below the poverty line (above that, they can purchase subsidized coverage in the marketplace). And, while states can increase the eligibility limits for parents, many non-expansion states continue to have very low eligibility limits for them — often only a fraction of the poverty line. In a typical non-expansion state, parents must have earnings of below about $9,000 a year (for a family of three) to qualify for Medicaid,[4] compared to earnings below $30,300 (138 percent of the poverty line) in most expansion states. (Expansion states may also set their thresholds higher, as Connecticut and the District of Columbia do.)

Racial health disparities are driven by many factors rooted in structural racism, such as discrimination and bias in the health care system; lack of investment in communities of color, which limits access to resources such as nutritious food and clean air; and educational disparities and employment discrimination, which result in a higher representation of people of color in jobs that don’t offer health coverage.

Medicaid expansion and subsidized private coverage through the Affordable Care Act reduced racial disparities in coverage. Between 2013 and 2019, the ACA helped reduce the uninsured rate for Black adults by 10 percentage points and the uninsured rate for Latino adults by 14.5 percentage points nationally.[5] But gaps persist: the uninsured rate for non-elderly white adults in the United States in 2019 was 9 percent, compared to 14 percent for Black adults, 26 percent for Latino adults, 25 percent for American Indian and Alaska Native adults, and 14 percent for Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander adults.[6] Asian adults had a slightly lower uninsured rate (8 percent) than white adults, an improvement compared to before the ACA, when Asian adults were more likely to be uninsured. But uninsured rates vary among different groups of people of Asian descent, reflecting varying degrees of poverty, immigration-related barriers to coverage, language access barriers, and other factors.[7] For example, between 2017 and 2018, people who are Korean or Vietnamese were significantly more likely to be uninsured than Indian, Chinese, or Filipino adults.[8]

States that have adopted the Medicaid expansion have narrowed the gap in uninsured rates between Black and Latino people and white people more so than states that haven’t expanded.[9] Between 2013 and 2019, the gap between white and Black adults shrank by 5.1 percentage points in expansion states versus 4.6 percentage points in non-expansion states, while the gap between white and Latino adults shrank by 10.1 percentage points in expansion states versus 7.5 percentage points in non-expansion states.[10]

Medicaid expansion has also helped lower non-elderly (aged 0 to 64) uninsured rates among American Indians and Alaska Natives, from 31 percent in 2013 to 20 percent in 2019 in expansion states, with a significantly smaller decline — from 29 percent to 25 percent — during the same period in non-expansion states.[11]

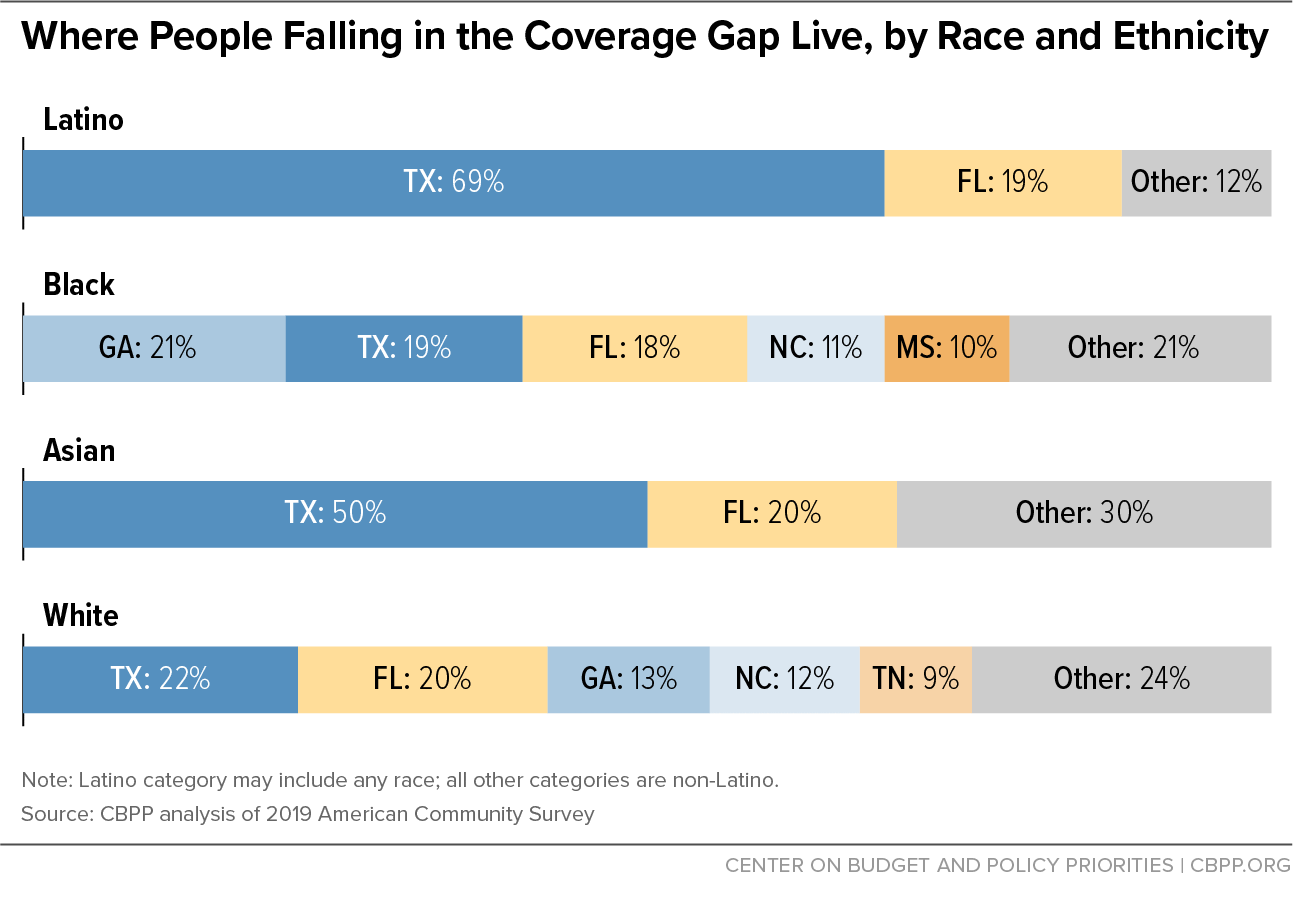

Most people in the coverage gap in 2019 lived in Southern states; these states varied in the racial and ethnic make-up of people in the coverage gap.[12] In Texas, people of color made up 74 percent of those in the coverage gap, with Latino adults alone comprising 55 percent. In Mississippi most of the coverage gap population was Black, and in both Georgia and South Carolina it was more than 40 percent Black. Over 70 percent of Asian adults and 88 percent of Latino adults in the coverage gap lived in Texas and Florida.[13] (See Figure 2 and Appendix Table 1.)

Disparities in access to care — measured, for example, by whether people have a usual source of care or forgo care due to cost — between white and Black non-elderly adults and between white and Latino non-elderly adults narrowed across the country after the major coverage provisions of the ACA took effect. There is also evidence that states that took the Medicaid expansion saw larger reductions in disparities. For example, disparities between white and Black adults and white and Latino adults in the share of people who avoided care due to cost narrowed more in Medicaid expansion states than in non-expansion states. And expansion states nearly eliminated disparities between the share of white and Black adults with a usual source of care, but disparities remained in non-expansion states.[14] While not all studies found that Medicaid expansion resulted in a reduction in disparities among racial and ethnic groups in particular care utilization, some showed smaller racial differences in access to certain health services after expansion, such as high-risk cancer surgery and HIV testing.[15]

Closing the coverage gap would also help narrow racial disparities in coverage among children. One in three people in the gap are parents with children at home. Extending coverage to parents increases enrollment among eligible children, research shows, so closing the coverage gap for adults would likely lead to coverage gains for children as well.[16] Latino children in non-expansion states are 2.5 times less likely to be insured than Latino children in expansion states and the gap between coverage rates for Latino and white children is growing faster in states without Medicaid expansion.[17]

Black and Latino adults are more likely than white adults to be diagnosed with a chronic disease.[18] This is influenced by factors such as racial inequities in health care access, unequal treatment people of color face in the health care system, and chronic stress from experiencing race-based discrimination. Medicaid expansion is associated with improved outcomes such as early diagnosis or treatment and fewer deaths related to chronic diseases, with people of color experiencing the greatest improvements. For example, expansion is associated with a reduction in mortality among people with end-stage renal disease, especially among Black people, and a reduction of disparities in timely treatment between Black and white people with advanced cancer diagnoses.[19]

Some of the strongest evidence of the role of Medicaid expansion in reducing racial disparities in health outcomes comes from research on health outcomes for people who give birth. A recent study of maternal mortality from 2006 to 2017 found that while the overall maternal mortality ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) worsened over the period, the increase was much less in expansion versus non-expansion states. The difference was significant for Hispanic mothers and was greatest among Black mothers. That makes closing the coverage gap key to addressing the United States’ Black maternal health crisis, in which Black mothers are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white mothers.[20]

The nation is also experiencing a behavioral health crisis, marked by rising deaths from overdose, sustained high levels of suicide, and a nationally declared public health emergency due to opioid misuse. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this crisis, especially for people of color. Black and Hispanic people have been more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression during the pandemic compared to non-Hispanic Asian and white people.[21] Black people in the U.S. with an opioid use disorder have less access to the full range of treatment options compared to white people.[22]

Medicaid expansion is associated with improved self-reported mental health and greater access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment.[23] Expanding coverage can remove affordability barriers for people of color and work alongside efforts to increase provider capacity and diversity and reduce cultural stigma surrounding mental health care.

Closing the Medicaid coverage gap also has economic benefits both to individuals who receive coverage and to the broader community. Extending health coverage to people in the gap can protect more people from medical debt and provide more flexibility for people to pursue opportunities for economic mobility, such as participating in training programs and starting or building businesses.

Medical debt is the top cause of bankruptcy in the United States and people of color are more likely to report trouble paying medical bills.[24] In 2018, about 28 percent of households with a Black family member and 22 percent with a Latino family member had medical debt, compared to 17 percent of households with a white family member and 10 percent with an Asian family member.[25]

A CBPP analysis of medical debt by ZIP code shows that there are racial disparities in medical debt in both expansion and non-expansion states, but the share of medical debt is significantly more prevalent overall in non-expansion states. The data analyzed provides the share of people with medical debt in majority-white communities (defined as ZIP codes where at least 60 percent of the population is white) and majority communities of color (where at least 60 percent of the population is non-white). In expansion states, 18 percent of people in communities that are majority people of color had medical debt in collections, versus 11 percent of majority-white communities. In non-expansion states the rates of medical debt and the racial gap in rates were higher: 28 percent of people in majority communities of color had medical debt compared to 16.7 percent of people in white communities.[26] (See Figure 3.)

Further reducing disparities in medical debt by closing the coverage gap will help address the racial wealth gap and keep more money in the pockets of people of color to pay for other needs and boost their financial security. Furthermore, closing the coverage gap can reduce the geographic differences in medical debt. Among regions in the United States, the average amount of medical debt in collections was highest in the South — where many of the states haven’t adopted the Medicaid expansion. Also, the drop in new medical debt from 2013 to 2020 was 34 percentage points greater in expansion than in non-expansion states, indicating the gains that closing the coverage gap may have.[27]

Expanding health coverage also plays a role in reducing disparities in the availability of health care providers that serve larger numbers of people of color. Most of the funds for closing the coverage gap go to payments for health care services, allowing more rural hospitals, safety net hospitals, and community health centers — many of which disproportionately serve people with low incomes and people of color — to stay open and even to provide more services in their communities.

Of the ten states with the most rural hospital closures since 2010, all but two are non-expansion states — and the two that have expanded Medicaid, Oklahoma and Missouri, only began the expansion in 2021.[28] In some of the non-expansion states, closed rural hospitals were more likely to be in counties with a higher share of Black residents. (See Figure 4.) For example, six out of the nine rural hospitals that closed in Georgia since 2005 were in counties with higher shares of people of color compared to the statewide average: five had a higher share of Black residents and one a higher share of Latino residents. Five out of eight shuttered rural hospitals in Florida were in counties with shares of Black residents above the state average, as were all four shuttered rural hospitals in South Carolina (though that state’s closures were not in the top ten).[29] While not all non-expansion states saw this kind of disparity, these examples show the importance of greater inclusion of communities of color in conversations about people’s access to health care in rural areas.

FIGURE 4

Notes: Ga. and S.C. are among the ten states with the most rural hospital closures since 2010; all but two (Mo. and Okla.) have refused to expand Medicaid (and those two expanded in 2021).

The median number of rural hospital beds is 25, according to UNC Sheps Center data from 2015, the latest available.

Source: CBPP analysis using data on rural hospital closures from the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, and county population information from American Community Survey 2019 5-year estimates.

Community health centers are also important sources of health services for people of color, who comprise 62 percent of community health center patients but 40 percent of the overall U.S. population.[30] In a 2018 survey, community health centers in Medicaid expansion states were more likely to report financial stability improvements since 2010 and coordination of care with community social service providers, compared to centers in non-expansion states.[31] Medicaid expansion was also associated with an increased share in community health center patients receiving screenings and treatment for conditions like asthma and hypertension, the latter condition seeing the greatest improvements for Hispanic patients in rural community health centers.[32]

Medicaid expansion also helped bring new federal funding for services provided through Indian Health Services, tribal health programs, and urban Indian health facilities or facilities contracted to provide services for American Indians. With new revenue from Medicaid expansion, Indian Health Services in Montana was able to increase the amount of care they provide and to allow more people to receive critical preventive care.[33] Medicaid is an important source of coverage for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN); about 55,000 non-elderly AIAN adults would gain coverage if the remaining states expanded their Medicaid programs.[34]

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

| State |

Total |

Asian |

Black |

Latino |

Other |

White |

| Total, non-expansion states |

2,211,000 |

29,000 |

617,000 |

613,000 |

60,000 |

893,000 |

| Alabama |

137,000 |

* |

53,000 |

* |

* |

75,000 |

| Florida |

425,000 |

6,000 |

109,000 |

118,000 |

12,000 |

179,000 |

| Georgia |

275,000 |

* |

130,000 |

24,000 |

* |

114,000 |

| Kansas |

44,000 |

* |

* |

8,000 |

4,000 |

26,000 |

| Mississippi |

110,000 |

* |

59,000 |

* |

* |

44,000 |

| North Carolina |

207,000 |

* |

68,000 |

19,000 |

12,000 |

106,000 |

| South Carolina |

105,000 |

* |

42,000 |

* |

* |

55,000 |

| South Dakota |

16,000 |

* |

* |

* |

6,000 |

9,000 |

| Tennessee |

119,000 |

* |

31,000 |

5,000 |

* |

79,000 |

| Texas |

766,000 |

14,000 |

118,000 |

422,000 |

12,000 |

200,000 |

| Wyoming |

7,000 |

* |

* |

* |

* |

5,000 |