States Are Using One-Time Funds to Improve Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Services, But Longer-Term Investments Are Needed

States are using one-time federal funding from legislation enacted in March to enhance, expand, and strengthen Medicaid home- and community-based services (HCBS), our review of 37 states’ plans shows. Most states include measures to deliver immediate relief to HCBS providers, expand provider recruitment, retention, and training initiatives, improve technology and access to telehealth, invest in quality improvement programs, expand efforts to address housing and other social determinants of health, expand access to specific services, increase supports for caregivers, and increase funding for people making transitions from institutions to the community.

These investments will help Medicaid HCBS systems, particularly the direct support workforce, recover from the stress the COVID-19 pandemic has placed on them. But to make the transformational changes needed so that more low-income seniors and people with disabilities are able to live and thrive in home- and community-based settings — where most people prefer to live — deeper and longer-term investments are needed. The recovery legislation that policymakers are now developing is a unique opportunity to deliver the federal support needed to begin these changes.

Pandemic-Stressed HCBS Systems Already Stretched Thin

Demand for Medicaid HCBS far outpaced availability even before the pandemic. Medicaid HCBS supports seniors and people with disabilities who need help with activities of daily living such as getting dressed and bathing, preparing and eating meals, and taking medications. These services help many people who would otherwise need institutional-level care remain in the community. Some states also provide other services, such as tenancy supports, case management, and home-delivered meals, to other targeted populations that do not meet institutional level of care requirements, such as people with a mental illness or substance use condition.

Unlike nursing home care, Medicaid HCBS is an optional benefit; this means states decide who is eligible and which services are covered for which populations. Due to these restrictions, many people who want to receive services in the community are unable to access Medicaid HCBS.Unlike nursing home care, Medicaid HCBS is an optional benefit; this means states decide who is eligible and which services are covered for which populations. Due to these restrictions, many people who want to receive services in the community are unable to access Medicaid HCBS. Hundreds of thousands of people are on waiting lists for HCBS.[1] Although these lists are an imperfect measure of unmet need, they are evidence of the gaps in the availability of HCBS for hundreds of thousands of people.[2] Also, direct care workers, who are more likely to be women and to be people of color compared to workers overall, are paid very low wages and have few opportunities for training or career advancement.[3] As a result, turnover in the field is high, which contributes to shortages even when services are available.[4]

The pandemic has taken an especially heavy toll on people who need long-term services and supports as well as the workforce that provides these services. The virus spread rapidly among people living and working in nursing homes and other congregate settings, especially before vaccines were available.[5] More than 30 percent of COVID-19 deaths in the United States have been among residents and staff at long-term care facilities.[6] This increased the urgency for many people to transition out of congregate settings, since seniors and people with disabilities who live at home are better able to isolate from the virus. Demand for home care workers has also increased since the pandemic began.[7] And the virus placed additional strain on people who were already receiving HCBS, as well as their caregivers, as people sought to protect themselves and their loved ones from becoming infected.[8]

American Rescue Plan Funding Can Help States Meet Immediate Needs

The American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act provides states with an opportunity to get an increase in the federal share of Medicaid costs for HCBS, specifically a 10-percentage-point increase in the federal government’s share of total Medicaid costs (the federal medical assistance percentage, or FMAP) for HCBS expenditures for 12 months beginning April 2021. The Congressional Budget Office estimates this provision could result in an additional $12.7 billion flowing to states.[9] To receive the additional funding, states must meet certain conditions. They cannot impose stricter HCBS eligibility levels and methodologies than were in place as of April 2021; they must maintain the amount, duration, and scope of HCBS benefits they already provide; and they must maintain HCBS provider payment rates at least as generous as those in place as of April 2021.[10] States must also use the additional funding to invest directly in activities that enhance, expand, or strengthen HCBS. States have until March 31, 2024, to spend the new funds they draw down as part of this opportunity.

States that meet these conditions and receive the additional federal funding have a great deal of flexibility to determine how to spend it, but they are required to submit an initial spending plan and quarterly updates to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for approval. CMS guidance provides examples of activities that would fulfill the requirements for HCBS investments, including activities to support COVID-19-related needs and activities to build states’ capacity to provide HCBS and to advance long-term services and supports (LTSS) rebalancing (to increase the proportion of long-term services and supports delivered through HCBS rather than in institutional settings) to address Medicaid’s programmatic bias toward institution-based care.

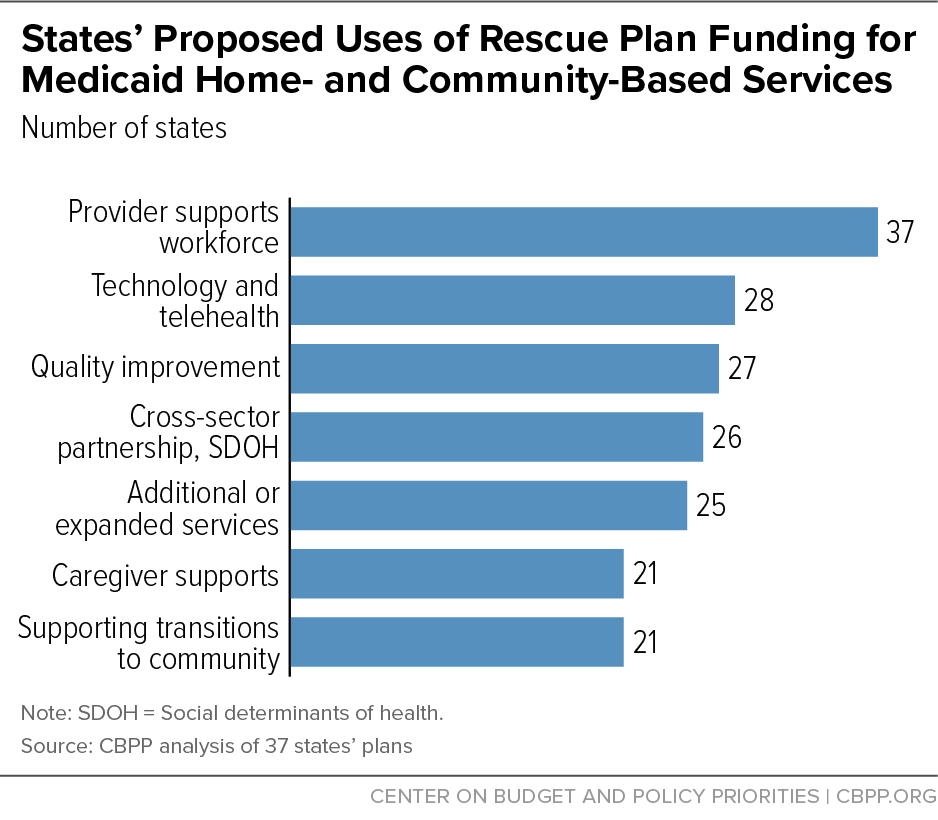

This analysis includes initial or preliminary plans from 37 states.[11] The plans vary widely, but the activities planned by the most states are increased provider rates and new workforce supports, investments in technology and telehealth, quality improvement initiatives, cross-sector efforts to address housing and other social determinants of health, additional or expanded services, caregiver supports, and activities to support transitions from institutions to the community. (See Figure 1.)

Additional Funding Needed to Make Lasting Improvements

The one-time funding states have now from the ARP provides a solid foundation for more systemic improvements that will help seniors and people with disabilities live in the community, including additional investments in HCBS and expansions of other critical supports such as housing vouchers.[12] The ARP funding for HCBS will also help to shore up strained systems and reinforce the stretched direct service workforce. But this one-time injection of new funding is insufficient to sustain the kind of long-term improvements that have been needed to improve access to HCBS since before the pandemic began.

President Biden’s American Jobs Plan proposed an unprecedented $400 billion investment in Medicaid HCBS and the direct care workforce.[13] Legislators subsequently introduced the Better Care, Better Jobs Act (BCBJA) to carry forward the President’s proposal.[14] The bill would create new financial incentives for states to create and implement HCBS improvement plans to make longer-term investments to enhance, expand, and strengthen Medicaid HCBS. To receive the additional federal funding, states would have to comply with maintenance-of-effort requirements around eligibility, services, and provider payments, provide enhanced access to certain services, and make significant improvements to provider payment rates and workforce supports.

Policymakers on the House Energy and Commerce Committee maintained the structure of the BCBJA in the HCBS provisions of the Build Back Better (BBB) legislation they approved in September, but they scaled back the federal government’s investment.[15] Most notably, the language approved by the committee reduced the FMAP increase for HCBS for states that implement improvement plans from 10 percentage points in the BCBJA to 7 percentage points, and eliminated the continuation of the ARP 10-percentage-point FMAP increase in the years leading up to implementation of HCBS improvement plans.[16] Even these scaled-back HCBS provisions in the BBB legislation are critically important to continue the momentum toward a broadly accessible, high-quality system of home- and community-based care for people who need it.

This is a landmark opportunity to make major improvements in access to Medicaid HCBS for seniors and people with disabilities and provide fair wages and career advancement for the workforce that cares for them. Policymakers must make difficult decisions about what is included in the bill and how much funding various provisions receive. These decisions — including the amount of additional federal funding available for HCBS and the way it is structured — will have a direct bearing on whether states ultimately opt to create HCBS improvement plans, how bold their plans will be, and how many people in Medicaid will have better access to higher-quality HCBS as a result.

States’ Choices Underscore Need for More Rental Assistance

There is broad recognition — by policymakers, researchers, state and local government agencies, direct health and human service providers, and health plans ― that deeper cross-sector partnerships supported by stronger cross-sector data integration can lead to meaningful improvements in access to services as well as in health and social outcomes.a This is particularly true for people with complex health needs such as those who qualify for HCBS. Twenty-six states propose to put some of their additional ARP funds toward initiatives that support these kinds of partnerships, data sharing, or other efforts to address social needs and social determinants of health.b (See Appendix Table 4.)

Most activities states propose in these categories relate to addressing beneficiaries’ housing needs, an area of increasing concern as millions of low-income people must pay very large shares of their income to avoid eviction or homelessness. States can use Medicaid funding to help people find and secure housing, make arrangements for moving, access services to help them maintain housing, and other housing-related activities. Some states cover these pre-tenancy and tenancy support services, and more should. But states are prohibited from using Medicaid to pay for room and board, such as ongoing rent costs, outside of institutional settings. Lack of affordable housing is a known barrier to transitioning to community-based settings. For example, in 2015, Colorado officials reported that about 75 percent of people who expressed interest in the Money Follows the Person program — which provides one-time funding to help people transition out of institutions and receive services in the community ― could not participate due to lack of affordable housing.c

Federal rental assistance is a proven strategy for making housing affordable for people with low incomes, but due to inadequate funding, just 1 in 4 families eligible for any type of federal rental assistance receive it. There are years-long waiting lists for vouchers in much of the country. This leaves low-income seniors and people with disabilities at greater risk of experiencing homelessness, housing instability, and unnecessary institutionalization.d The severe shortage of rental assistance contributes to significant hardship for people with disabilities even in good economic times, and the effect was especially tragic during the COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis.

In addition to additional funding for Medicaid HCBS, the committee markup of the House Build Back Better legislation also includes $90 billion for two key rental assistance programs ($15 billion for Project-Based Rental Assistance and $75 billion for Housing Choice Vouchers).e When fully phased in, these investments could make housing affordable for as many as 1 million more families and individuals. This would sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding and allow low-income people to spend more on other basic needs such as food and medicine.f

The Senate has not yet released its language for the recovery bill, but the Senate budget resolution includes significant allocations for the committees responsible for housing programs. Voucher expansion could help many disabled people who want to live in the community move out of nursing homes, psychiatric facilities, and other congregate facilities, especially if paired with more funding for Medicaid HCBS. Investing in additional HCBS without also ensuring access to affordable housing could leave behind many disabled people who have the lowest incomes and face the greatest barriers to living in the community. Increasing funding for HCBS and vouchers is critical for promoting equitable access to community-based living for all low-income seniors and people with disabilities.

a Peggy Bailey, “Housing and Health Partners Can Work Together to Close the Housing Affordability Gap,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 17, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/housing-and-health-partners-can-work-together-to-close-the-housing-affordability.

b Social needs refer to individual needs for housing, food, and other supports. Social determinants of health are the systemic social and economic conditions in a community that influence health and well-being.

c Carol Irvin et al., “Money Follows the Person 2015 Annual Evaluation Report,” Mathematica Policy Research, May 11, 2017, https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/money-follows-the-person-2015-annual-evaluation-report.

d Anna Bailey, Raquel de la Huerga, and Erik Gartland, “More Housing Vouchers Needed to Help People With Disabilities Afford Stable Homes in the Community,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 6, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/more-housing-vouchers-needed-to-help-people-with-disabilities-afford-stable-homes.

e Ann Oliva, “Recovery Legislation’s Housing Voucher Investments Would Make Major Progress in Cutting Homelessness, Housing Instability,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 9, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/recovery-legislations-housing-voucher-investments-would-make-major-progress-in-cutting.

f Ann Oliva, “Congress Has Rare Opportunity to Address Housing Affordability and Homelessness Crisis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 31, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/congress-has-rare-opportunity-to-address-housing-affordability-and-homelessness-crisis.

Appendix: States’ Proposed Activities to Expand, Enhance,

or Strengthen Medicaid HCBS

This appendix describes which states plan activities in the seven most common categories of activities in states’ ARP HCBS implementation plans. The information was obtained from state implementation plans available on state Medicaid agency websites. This is not a comprehensive accounting of the activities states have proposed. This analysis shows which states have proposed activities in the seven most common categories:

- Provider and workforce supports;

- Technology and telehealth;

- Quality improvement initiatives;

- Cross-sector initiatives to address housing and other social determinants of health;

- Increasing or expanding services;

- Caregiver supports; and

- Supporting community transition.

The states included in this analysis are: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Additional states may have submitted implementation plans to CMS, but these were not publicly available at the time of publication.

Provider and Workforce Supports

All 37 plans included in this analysis included activities related to supporting HCBS providers and the direct service workforce, including COVID-19-related provider rate increases (24 states); special payments such as hazard pay (20 states); recruitment and retention activities (19 states); training and career development opportunities (27 states); expanding behavioral health capacity (13 states); and broadly increasing provider/workforce capacity through various grant programs and initiatives (17 states).

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider and Workforce Supports | ||||||

| States | Provider Rate Increases | Special Payments | Recruitment or Retention Activities | Training | Expanding Behavioral Health Capacity | Other Provider/ Workforce Initiatives |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Arizona | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | X | X | ||||

| California | X | X | X | X | ||

| Colorado | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | |||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X | |

| District of Columbia | X | X | X | X | ||

| Florida | X | X | X | |||

| Georgia | X | X | X | |||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | ||

| Indiana | X | X | ||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | ||

| Maine | X | X | ||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | ||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Mississippi | X | |||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | ||

| Nebraska | X | |||||

| Nevada | X | X | ||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | |

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | ||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | |

| North Carolina | X | X | X | |||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | ||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | |||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | ||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | |||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | ||

| Utah | X | X | X | |||

| Vermont | X | X | X | |||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||

| Washington | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | |||

| Wyoming | X | X | ||||

| Total | 24 | 20 | 19 | 27 | 13 | 17 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

Technology and Telehealth

Twenty-eight states included investments related to technology and telehealth. Some of these build on earlier efforts to expand the use of telehealth to help people access care while maintaining distance when the pandemic began.[17] States propose a range of strategies, including providing grants and incentives to providers to improve their telehealth platforms and delivery models, and providing additional tablets, assistive technology, training and support to help beneficiaries access telehealth. Other technology investments include providing remote patient monitoring devices and support, creating or improving state platforms for provider reporting and billing, and expanding the use of electronic health records.

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 | |

|---|---|

| Technology and Telehealth | |

| States | Activities to Improve Access to Telehealth and/or

Other Technology Improvements |

| Alabama | X |

| Arizona | X |

| Arkansas | X |

| California | X |

| Colorado | X |

| Connecticut | X |

| Delaware | X |

| District of Columbia | X |

| Florida | X |

| Georgia | X |

| Illinois | X |

| Indiana | X |

| Kentucky | X |

| Maine | X |

| Massachusetts | X |

| Minnesota | X |

| Mississippi | |

| Missouri | X |

| Nebraska | X |

| Nevada | |

| New Hampshire | |

| New Jersey | |

| New Mexico | X |

| New York | |

| North Carolina | X |

| Pennsylvania | X |

| Rhode Island | X |

| South Carolina | X |

| Tennessee | X |

| Texas | X |

| Utah | |

| Vermont | X |

| Virginia | |

| Washington | X |

| West Virginia | |

| Wisconsin | |

| Wyoming | X |

| Total | 28 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

Quality Improvement Initiatives

Twenty-seven states included quality improvement investments in their plans. These include member engagement surveys and analyses, research on the HCBS workforce, development of new quality measures, improvements to quality oversight activities, efforts to make HCBS more culturally informed and responsive, updates to critical incident management systems, and implementation of delivery system reforms (value-based purchasing, pay for performance, etc.).

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 | |

|---|---|

| Quality Improvement Initiatives | |

| States | Quality Improvement Initiatives |

| Alabama | |

| Arizona | X |

| Arkansas | X |

| California | X |

| Colorado | X |

| Connecticut | X |

| Delaware | X |

| District of Columbia | X |

| Florida | X |

| Georgia | X |

| Illinois | |

| Indiana | X |

| Kentucky | |

| Maine | X |

| Massachusetts | X |

| Minnesota | X |

| Mississippi | X |

| Missouri | X |

| Nebraska | |

| Nevada | X |

| New Hampshire | |

| New Jersey | |

| New Mexico | X |

| New York | X |

| North Carolina | X |

| Pennsylvania | |

| Rhode Island | X |

| South Carolina | X |

| Tennessee | |

| Texas | X |

| Utah | |

| Vermont | |

| Virginia | X |

| Washington | X |

| West Virginia | X |

| Wisconsin | X |

| Wyoming | X |

| Total | 27 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

Cross-Sector Initiatives to Address Housing and Other Social Determinants of Health

Twenty-six states proposed to use some of their additional funds on initiatives that support cross-sector partnerships, data integration, or other efforts to address social needs and social determinants of health. Of these states, 14 propose activities to address beneficiaries’ housing needs:

- Homelessness reduction and/or prevention activities (California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Washington)

- Rental assistance, i.e., directly funding, or other activities to promote better access (California, Delaware, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington)

- Expansion of tenancy supports and other supportive housing models (Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York, and Utah)

- Increased staffing to support health-housing partnerships (District of Columbia and Indiana)

- Housing development (Indiana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Washington)

In addition to these activities that directly address Medicaid enrollees’ housing needs, Kentucky proposes to use a portion of its research funds to assess housing needs among older adults and people with disabilities and develop new strategies to meet the needs identified. Washington proposes to use a portion of its funds to support improvements to recovery housing, including creating and maintaining a registry of approved recovery residences and providing technical assistance and financial support to residence operators.

Other proposed activities to promote cross-sector collaboration and address social needs and social determinants of health include one-time grants to promote innovative solutions to addressing social needs, additional supports related to meals, employment, and transportation, and investments in technology infrastructure to support cross-system data integration between Medicaid HCBS and Medicare, departments of corrections, other state agencies, and community-based organizations.

| APPENDIX TABLE 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressing Social Needs and Promoting Cross-Sector Work | ||||||||

| Health-Housing Activities | ||||||||

| States | Homelessness reduction /prevention | Rental assistance a | Tenancy supports/ supportive housing | Staffing for health-housing partnerships | Housing development | Cross-sector partnerships (other than housing) | Cross-sector data integration | Addressing SDOH other than housing |

| Alabama | ||||||||

| Arizona | X | |||||||

| Arkansas | ||||||||

| California | X | X | X | |||||

| Colorado | ||||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | ||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | ||||

| District of Columbia | X | |||||||

| Florida | ||||||||

| Georgia | ||||||||

| Illinois | ||||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Kentucky | X | X | ||||||

| Maine | ||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | |||||

| Minnesota | X | X | ||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | |||||

| Missouri | X | |||||||

| Nebraska | ||||||||

| Nevada | X | |||||||

| New Hampshire | X | |||||||

| New Jersey | X | |||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | ||||

| New York | X | X | X | |||||

| North Carolina | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | |||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | ||||||

| South Carolina | ||||||||

| Tennessee | ||||||||

| Texas | X | |||||||

| Utah | X | |||||||

| Vermont | X | X | ||||||

| Virginia | X | |||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | ||||||

| Wisconsin | X | |||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||

| Total | 6 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 10 |

a Rental assistance includes states that propose providing rental assistance directly as well as states that propose measures to increase access to existing sources of rental assistance.

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

Additional or Expanded Services

Twenty-five states plan to use the additional funding to add services or increase benefit levels for existing services. States’ programs vary widely, and the services added or expanded on vary as well. They include (but are not limited to) investments such as home-delivered meals, additional behavioral health benefits for certain populations, tenancy supports, transportation, and increased caps for home modifications and repairs. A few states propose expanded services related specifically to pandemic response, such as increasing allowable case management services to address COVID-19-related concerns in South Carolina, and providing additional funding to schools to help them address health needs of students with disabilities as they return to in-person school in New Hampshire.

Eleven states (Alabama, California, Florida, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and West Virginia) also intend to use funds to add waiver slots/reduce waiting lists for certain HCBS waivers. States’ waiting list policies vary — with some assessing service eligibility at the time an individual is placed on a waiting list, and others merely reflecting an individual’s interest in receiving services should a slot become available. Texas, in the latter category, proposes to use funds to work with a contractor to reach out to individuals on waiting lists to determine needs in addition to increasing the overall number of HCBS waiver slots. New Mexico and North Carolina propose improvements in waiting list databases and management, as well as adding waiver slots. Kentucky did not propose adding waiver slots, but the state did propose using funds to study waitlist procedures and to develop and conduct an assessment of people currently on waiting lists, with a goal of connecting people to the Medicaid state plan or community services to better meet immediate needs.

| APPENDIX TABLE 5 | |

|---|---|

| Increasing or Expanding Home- and Community-Based Services | |

| States | Adding New Services and/or Expanding Coverage of Certain Services |

| Alabama | X |

| Arizona | X |

| Arkansas | |

| California | X |

| Colorado | X |

| Connecticut | |

| Delaware | X |

| District Of Columbia | X |

| Florida | |

| Georgia | X |

| Illinois | X |

| Indiana | |

| Kentucky | X |

| Maine | |

| Massachusetts | X |

| Minnesota | X |

| Mississippi | X |

| Missouri | X |

| Nebraska | |

| Nevada | X |

| New Hampshire | X |

| New Jersey | X |

| New Mexico | X |

| New York | X |

| North Carolina | X |

| Pennsylvania | X |

| Rhode Island | X |

| South Carolina | X |

| Tennessee | |

| Texas | X |

| Utah | |

| Vermont | |

| Virginia | |

| Washington | X |

| West Virginia | |

| Wisconsin | |

| Wyoming | X |

| Total | 25 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

Caregiver Supports

Family caregivers have been particularly strained since the pandemic began, experiencing more fatigue, anxiety, and other symptoms of poor physical health than non-caregivers.[18] Twenty-one states plan to provide additional supports or training to these individuals. This includes additional direct payments, trainings on topics ranging from cultural competency to supports for people with specific kinds of disabilities, investments in caregiver resource centers, respite care, additional adult day services, and expanded infrastructure for self-directed care.

| APPENDIX TABLE 6 | |

|---|---|

| Providing More Caregiver Supports | |

| States | Additional Caregiver Supports |

| Alabama | X |

| Arizona | X |

| Arkansas | |

| California | X |

| Colorado | X |

| Connecticut | X |

| Delaware | X |

| District of Columbia | |

| Florida | |

| Georgia | |

| Illinois | X |

| Indiana | X |

| Kentucky | X |

| Maine | X |

| Massachusetts | X |

| Minnesota | X |

| Mississippi | |

| Missouri | |

| Nebraska | |

| Nevada | |

| New Hampshire | |

| New Jersey | |

| New Mexico | X |

| New York | |

| North Carolina | |

| Pennsylvania | X |

| Rhode Island | |

| South Carolina | X |

| Tennessee | X |

| Texas | X |

| Utah | X |

| Vermont | X |

| Virginia | |

| Washington | X |

| West Virginia | X |

| Wisconsin | |

| Wyoming | |

| Total | 21 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

Community Transition

A key component of Medicaid rebalancing (away from a majority of LTSS spending on institution-based care and toward a greater proportion of spending on HCBS) is ensuring ample opportunities for individuals in institutions to move to community-based care. Twenty-one states proposed initiatives related to improving people’s transitions from institution-based to community-based settings. Most states did not provide details on how the investments to improve community transition would be used, although several mentioned specific activities to increase beneficiaries’ access to affordable housing, including first/last month’s rent, security deposits, and tenancy supports in addition to more traditional transition supports such as home modifications and moving assistance.

| APPENDIX TABLE 7 | |

|---|---|

| Supporting Community Transition | |

| States | Initiatives to Improve Community Transition |

| Alabama | X |

| Arizona | |

| Arkansas | X |

| California | |

| Colorado | X |

| Connecticut | X |

| Delaware | |

| District of Columbia | X |

| Florida | |

| Georgia | |

| Illinois | X |

| Indiana | X |

| Kentucky | |

| Maine | |

| Massachusetts | X |

| Minnesota | X |

| Mississippi | |

| Missouri | |

| Nebraska | X |

| Nevada | |

| New Hampshire | X |

| New Jersey | X |

| New Mexico | X |

| New York | X |

| North Carolina | X |

| Pennsylvania | X |

| Rhode Island | X |

| South Carolina | X |

| Tennessee | |

| Texas | |

| Utah | X |

| Vermont | |

| Virginia | |

| Washington | X |

| West Virginia | |

| Wisconsin | |

| Wyoming | X |

| Total | 21 |

Source: CBPP analysis of 37 states’ spending plans for implementation of Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan Act

End Notes

[1] MaryBeth Musumeci, Molly O’Malley Watts, and Priya Chidambaram, “Key State Policy Choices About Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 4, 2020, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/key-state-policy-choices-about-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services/.

[2] States determine whether to keep HCBS waiting lists and, if they do, how to administer them. Some states screen people for HCBS waiver eligibility before they are placed on a waiting list, while other states add any individual interested in receiving services to a list and determine eligibility when a slot becomes available. Because states’ HCBS offerings vary so widely, waiting lists are also a poor comparative measure of need. Better data collection is needed to develop more accurate measures of HCBS need.

[3] Sarah True et al., “COVID-19 and Workers at Risk: Examining the Long-Term Care Workforce,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 23, 2020, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-and-workers-at-risk-examining-the-long-term-care-workforce/.

[4] Stephen Campbell et al., “Caring for the Future: The Power and Potential of America’s Direct Care Workforce,” PHI, January 12, 2021, https://phinational.org/resource/caring-for-the-future-the-power-and-potential-of-americas-direct-care-workforce/.

[5] “Rates of COVID-19 Among Residents and Staff Members in Nursing Homes — United States, May 25–November 22, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 70, No. 2, January 15, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/pdfs/mm7002e2-H.pdf.

[6] “State COVID-19 Data and Policy Actions,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 2, 2021, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-covid-19-data-and-policy-actions/.

[7] Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein, “Placing a Higher Value on Direct Care Workers,” Commonwealth Fund, July 1, 2021, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/jul/placing-higher-value-direct-care-workers.

[8] Madeline R. Sterling et al., “Experiences of Home Health Care Workers in New York City During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Qualitative Analysis,” JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 180 No. 11, August 4, 2020, pp. 1453-1459, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2769096.

[9] Congressional Budget Office, “Estimated Budgetary Effects of H.R. 1319, American Rescue Plan Act of 2021: Detailed Tables,” March 10, 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57056.

[10] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “SMD#21-003: RE: Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency,” May 13, 2021, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd21003.pdf.

[11] CMS stated in its guidance that it intends to post all states’ spending plans publicly, but as of the date of publication, this information was not yet available on CMS’s website. The analysis in this paper reflects the plans that were publicly accessible through each state’s Medicaid agency website. As such, it may not represent a comprehensive list of all state plans submitted to CMS. See Appendix for a list of states included in this analysis.

[12] Anna Bailey, Raquel de la Huerga, and Erik Gartland, “More Housing Vouchers Needed to Help People With Disabilities Afford Stable Homes in the Community,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 6, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/more-housing-vouchers-needed-to-help-people-with-disabilities-afford-stable-homes.

[13] White House, “Fact Sheet: The American Jobs Plan,” March 31, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/31/fact-sheet-the-american-jobs-plan/.

[14] S.2210, “Better Care Better Jobs Act,” https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2210.

[15] Rachel Roubein, “Biden’s unlikely to get his full funding ask for home health care,” Washington Post, September 14, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/09/14/biden-unlikely-get-his-full-funding-ask-home-health-care/. For the text of the Medicaid subtitle of the BBB approved by the Energy and Commerce Committee, see: https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF00/20210913/114039/BILLS-117-G-A000370-Amdt-1.pdf.

[16] For more on the Medicaid provisions in the Build Back Better Act, see Jennifer Sullivan, Anna Bailey, and Jennifer Wagner, “Build Back Better Legislation Makes Major Medicaid Improvements,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 17, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/build-back-better-legislation-makes-major-medicaid-improvements.

[17] Jessica Schubel, “States Are Leveraging Medicaid to Respond to COVID-19,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated September 2, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-leveraging-medicaid-to-respond-to-covid-19.

[18] Paula Span, “Family Caregivers Feel the Pandemic’s Weight,” New York Times, updated July 24, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/health/coronavirus-home-caregivers-elderly.html; Sung S Park, “Caregivers’ Mental Health and Somatic Symptoms During COVID-19,” Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Vol. 76, Issue 4, April 2021, e235–e240, https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/76/4/e235/5879757.

More from the Authors