Cash assistance helps provide stability to families through life’s challenges. A cash assistance program whose benefits are not conditioned on when or how someone has children or on caregivers’ past or present conduct is one that recognizes that they know how to take care of themselves and their children when their family falls on hard times. But Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the nation’s oldest program for providing cash assistance to families with very low income, is instead laden with undignified, coercive requirements designed to exclude people due to past conduct rather than current need, and in some cases even to control their reproductive decisions. These policies send messages that parents seeking assistance are irresponsible, criminal, or undeserving of support. And while these policies affect all TANF families, they are extensions of racist and sexist polices of TANF’s predecessors and reinforce anti-Black narratives.

TANF’s time limits and provisions that take away benefits for not meeting work requirements get much attention, rightly, as key contributors to caseload decline over the past 25 years. But behavioral requirements and exclusions that pre-date work requirements and time limits were a key strategy in limiting access for Black and unmarried mothers under TANF’s predecessors and create hassles and barriers in TANF participation today. Caseworkers in early state and local mothers’ pension and Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) programs largely served families who were seen as “deserving” — the children of white widows — by denying aid to Black and unmarried mothers on supposed moral and conduct grounds. Later, to control costs and remove Black and unmarried mothers and their children from ADC, policymakers instituted policies explicitly limiting eligibility based on family structure or mothers’ relationships with men.[2] Some went as far as proposing sterilizations of mothers in ADC, a program that was later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC).

In the 1960s and 1970s the welfare rights movement won key limitations on these arbitrary eligibility policies, but then efforts to “reform” AFDC strengthened and with them came new behavioral requirements and reproductive control measures designed to promote mothers’ “personal responsibility” and thereby make them “deserving” of assistance. Policymakers and the media elevated false narratives of Black women and Black communities to justify paternalistic policies with seemingly race-neutral language. Some of these policies and others like them remain in effect today, stripping the dignity of not just Black mothers seeking assistance but all such parents and making TANF a weak support for when families fall on hard times.

This paper is part of a series examining how racist and sexist attitudes toward Black women have shaped the design of TANF and other cash assistance programs.[3] This installment traces behavioral and reproductive control policies from their origin in enslavement and Jim Crow through current-day TANF policies that are based on anti-Black narratives of promiscuity, irresponsibility, and criminality. TANF cash assistance can be a critical support to families in a crisis, but it needs to center the needs of Black mothers as posited in the “Black Women Best” framework, which argues that “if Black women — who, since our nation’s founding, have been among the most excluded and exploited by the rules that structure our society — can one day thrive in the economy, then [the economy] must finally be working for everyone.”[4]

Under this framework, policymakers should eliminate policies that have historically targeted Black mothers and promote policies that provide meaningful support to Black parents. Using this framework, we propose that:

- Federal policymakers bar TANF’s behavioral requirements and other eligibility exclusions.

- TANF agencies refocus on helping families address immediate crises and improve their long-term well-being.

- States take action now — without waiting for a potentially long federal legislative process — to eliminate punitive policies around behavioral requirements, reproductive controls, and other exclusions.

Other TANF changes we recommend but that are outside the scope of this paper include establishing a federal minimum benefit and improving program access by replacing mandatory work requirements with programs that help TANF recipients to improve their long-term well-being by helping them to address immediate crises and prepare for quality jobs. For the full range of proposals, see “Cash Assistance Should Promote Equity: Applying the “Black Women Best” Framework to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.”[5]

Reproductive and Behavioral Controls Stem From Enslavement and Jim Crow

Labeling Black women as promiscuous, irrational, and negligent, white enslavers employed forced reproduction to exploit and control enslaved Black women while maximizing their economic returns.[6] Under enslavement, Black women were punished when they did not bear children. State laws further incentivized the sexual abuse of Black women: the rape of an enslaved woman was not recognized as a crime and all children born to enslaved women were legal property of the mother’s enslaver.[7] Even pregnancy did not always protect women. In one especially horrific example, some enslavers dug holes in the ground and forced pregnant women to put their belly in the hole to “protect” the child as they were whipped.[8] The expectation that Black women have children did not reduce the amount of work demanded of them; some pregnant women worked to the point of miscarriage and new mothers had to work, sacrificing the health — and often the lives — of their babies, in addition to their own.[9] Enslaved Black mothers also had to care for white children while caring for their own or other enslaved children.

Emancipation and Reconstruction offered a brief hope for a transformed system, but soon the freedom many Black people experienced was not much different from enslavement. Post-Reconstruction, many Black women still did not have full control over their sexual and reproductive decisions. White men systematically raped Black women and girls in a parallel to the reign of terror of lynchings of thousands of Black people.[10] In the South, Jim Crow laws controlled other behaviors by denying Black people’s right to vote and telling them where they could eat, walk, sit, and spend their money, among other things.

Many anti-Black narratives from this time persist, but two that relate to cash assistance policies are “the Jezebel,” the immoral Black mother, and “the mammy,” who was devoted to the care of white children but negligent of her own. The Jezebel is a hypersexualized image of an enslaved woman that white men used to justify their sexual abuse of Black women by painting them as promiscuous and immoral. It was perpetuated in post-enslavement laws and practices based on the assumption that without the moral guidance of white policymakers, Black women would regress to their “natural” promiscuous state. Under this narrative, Black women would have many children outside of marriage, creating high costs in public programs and contributing to crime.[11]

The contrived image of the mammy was as a mother figure, devoted to the enslaver’s children with little or no regard for her own. The mammy figure painted the picture of Black mothers as incapable of motherhood without constant supervision from white people. Without the influence of morally superior white women, went the stereotype, Black mothers had uncontrollable animalistic impulses.[12] Furthermore, post-enslavement Black mothers who worked for pay, many in the homes of white families, were described as proving their negligence by working late and leaving their children alone.[13]

Throughout the 20th century, policymakers and others invoked these two false narratives to control Black people’s lives, and in particular Black women’s reproductive and parenting decisions. And though their roots are in the enslavement of Black people, these images of motherhood are associated with parents receiving cash assistance today.

As they do under TANF, states and localities had broad discretion in determining eligibility for mothers’ pension programs,[14] and for much of ADC/AFDC’s history. Caseworkers had significant power to interpret rules and policies in making eligibility determinations and largely based these determinations on applicants’ “deservingness” — a concept that was explicitly based on white, middle-class ideas of morality and character and implicitly designed to exclude Black women.[15] While race was not always explicit in the statutory or regulatory language of deservingness, policymakers voiced their intention to restrict access for Black families or targeted Black families in the implementation of punitive policies. Caseworker prejudice was another barrier to assistance for many Black families.

Many states framed their eligibility rules using “suitable home” policies. These were ostensibly designed to protect children from maltreatment and support their healthy development but gave caseworkers and local administrators latitude to deny aid based on moral determinations of a mother’s fitness for child rearing, resulting in the exclusion of children of Black and unmarried mothers. Some states denied aid by making overbroad use of the technical concept of “deprivation,” a statutory ADC provision that determines eligibility for children based on the loss of support due to an absent or incapacitated parent. State policymakers also used anti-Black narratives to argue for sterilization of ADC mothers.

Caseworkers Coerced Behaviors and Limited Black Women’s Participation

The types of families intended for mothers’ pension and ADC programs were those who were “deserving.” This concept was not always clearly defined but included qualities such as having “worthy character” and being “reasonably efficient,” as a report from a 1909 White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children stated.[16] State mothers’ pension programs generally had two broad considerations of eligibility: 1) the father’s status, such as if he was dead, disabled, had abandoned the family, or was not married to the mother; and 2) whether the mother was “physically, mentally, or morally” fit.[17] In this way, states and localities sought to only provide cash aid to children in “suitable homes” who would be an “asset to society.”[18]

Mothers’ pension and early ADC caseworkers were the ones identifying these families and had broad discretion in making determinations. They conducted in-home assessments and observed the mother’s interactions with her children, the children’s health and conduct, and the decency of the home itself. A family’s approval or denial of aid was based on the caseworker’s opinion of if and how well a mother engaged in certain behaviors. Sometimes families who were not initially determined to be “suitable” were put on trial periods and only received ADC benefits if the mothers’ behavior conformed to the caseworker’s standards,[19] which were themselves based on white-Anglo, middle-class norms of morality and home life. For example, caseworkers urged celibacy, thriftiness, cleanliness, “domesticity centered on the child,” Christian piety, and use of the English language for mothers’ whose first language wasn’t English.[20]

Policymakers and caseworkers also gave significant attention to mothers’ relationships with men. Generally, mothers’ pension programs and many early ADC programs excluded most unmarried mothers. Less than one-tenth of a percent of mothers’ pension program children had unwed mothers, a 1931 study found;[21] among ADC children living with their mothers in 1937, only 3.5 percent lived with unmarried mothers.[22] One Michigan mother had to sign an affidavit saying “I will not have any male callers coming to my home….[S]hould I violate this agreement, the children will be taken from me.”[23] States only intensified their surveillance of mothers’ interactions with men in the mid-century.

Further exemplifying the effect that caseworker discretion and prejudice had in excluding Black families, the same 1931 study found only 3 percent of children receiving mothers pensions whose race was reported had a Black mother. The majority of Black recipients were from two states — Ohio and Pennsylvania — where Black people accounted for less than 5 percent of the total population. Only three of Mississippi’s counties had mothers’ pension programs even though Black people accounted for about half of the state’s population.[24] Between 1937 and 1940, Black families made up 14 to 17 percent of the ADC caseload, with even smaller shares in Southern states, despite their larger Black population. Caseworkers also did not apply “suitable home” standards evenly across race. One study found that in states with these standards, caseworkers applied stricter interpretations to families living in areas with higher concentrations of Black people. In Wayne County, Michigan (where Detroit is located), which had a large proportion of the state’s Black population, caseworkers focused on rooting out “unsuitable homes” so intensely, a federal review called its program “coercive.”[25]

With states using “suitable home” policies to ignore the dire needs of Black families and families with unwed mothers, federal administrators put out guidance to encourage state programs to consider the poverty of the family when determining eligibility. But state program administrators, particularly in the South, either ignored or found ways to get around these guidelines. In the late 1930s, one ADC field supervisor in a Southern state said Black families “have always gotten along,” and if made eligible for assistance, “all they’ll do is have more children,” articulating the false “welfare queen” trope decades before the term gained popularity. When one Southern county begrudgingly provided aid to 250 Black families, the field reporter noted program officials had “grave doubt about the wisdom of this decision but otherwise [the families] would have starved.”[26]

Between the 1940s and 1960s, the number of families receiving ADC dramatically increased. After the Old Age and Survivors Insurance program expanded eligibility in 1939, white widows largely left ADC.[27] Many Black families who moved out of the rural South were better able to access ADC, contributing to the increase of Black families on the program throughout the 1950s.[28] In response, states started passing laws designed for, as Georgia officials put it, “cleaning up” the caseload.[29] More states instituted “suitable home” requirements, and policymakers used these and other laws to respond to concerns about types of mothers in the program and the growing costs.

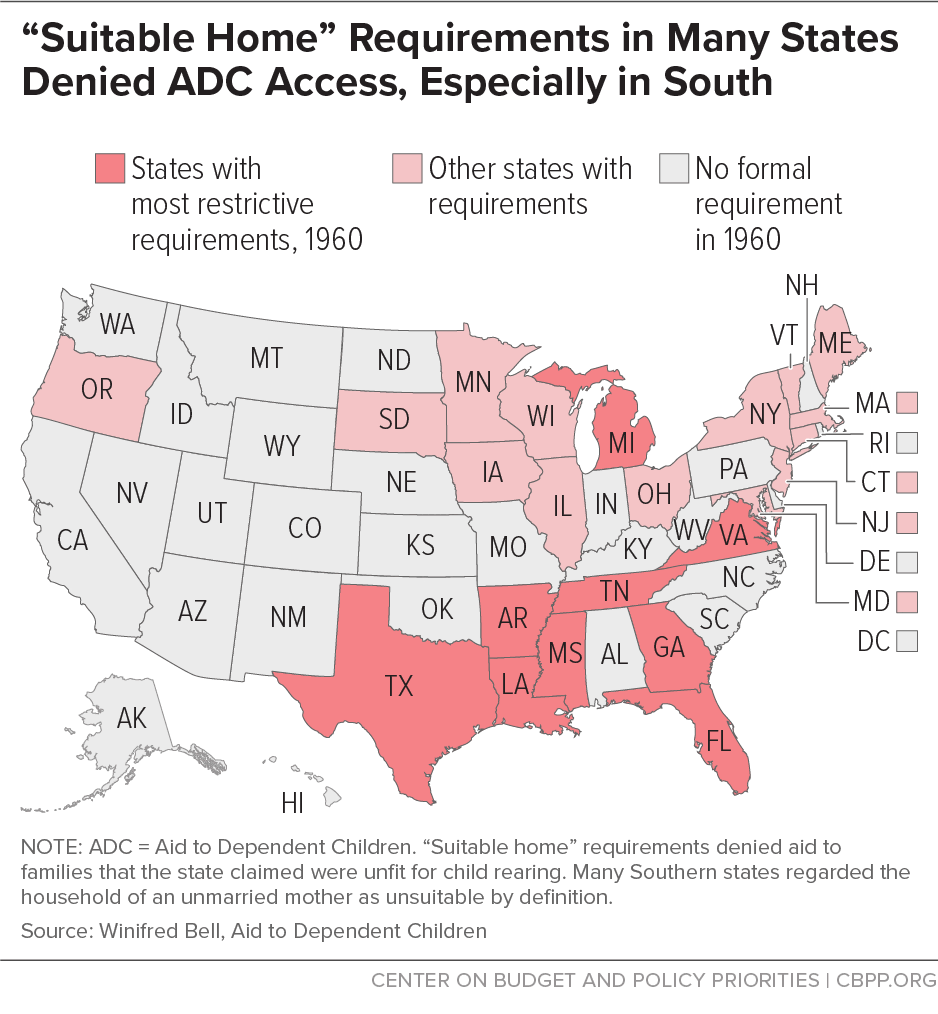

As in prior decades, ADC policies and laws did not mention race. Yet among the 23 states with “suitable home” requirements, the most punitive were in states with high Black populations or targeted Black families. Some policymakers were clear about their intent even if the policy was silent on race. The head of Georgia’s Department of Public Welfare, for example, said in 1951 that the program would save money “mainly by limiting aid to children of unwed [Black] mothers,” (the brackets indicating use of an outdated term to describe Black people).[30] That year the state’s “suitable home” requirement would have denied additional benefits to mothers with “more than one illegitimate child.”[31] The Georgia legislature repealed the law after the federal government raised legal questions, but state policymakers instituted another rule in 1952 that still denied aid to children of unwed mothers, getting around federal objections.[32]

“Suitable home” policies in Arkansas, Florida, Virginia, Tennessee, and Texas equated a mother’s “immoral” or illegal sexual behavior with child neglect.[33] (See Figure 1 for a map of “suitable home” requirements by state.) Florida’s legal definition of “failure to provide a moral environment for children” included “engaging in promiscuous conduct” and the presence of “illegitimate” children, or those born to unmarried parents. The state threatened to remove children from the home if offending mothers did not voluntarily release the children to extended family. Florida officials were likelier to scrutinize Black ADC families than white ones under this definition of neglect. The state would drop the case if the family withdrew from the program, illustrating that the real purpose of these policies was not to improve child well-being but to remove families from cash assistance programs. Many families did not even apply to ADC for fear their children could be taken away.[34]

In perhaps the most extreme example, Louisiana’s 1960 “suitable home” law, part of a larger segregation legislative package, drew national and international attention for its blatant targeting of Black families and the number of families it cut off.[35] A home was deemed “unsuitable” if a family had “illegitimate” children; if the parents were in a common-law marriage, which was more common among Black families;[36] or if the mother was deemed “promiscuous.” The law stated that “no assistance shall be granted to a child living with its mother if the mother has had an illegitimate child after receiving assistance from the department of public welfare.” Within three months, these laws cut off more than 6,000 families (about 23,000 children) from the program; 95 percent of the children in those families were Black. Later that year about half of the families who were cut off had their reapplications rejected or did not reapply. Some of the families who did not reapply did not know they could.[37]

Another sexist policy called “substitute father” (or “man-in-the-house”[38]) rules targeted mothers’ romantic and sometimes platonic relationships. That is, if a mother had a non-[DP1] disabled romantic partner, he should be providing financial support to the family and the child should not be considered “deprived of parental support,” policymakers argued, using a questionable application of the statutory definition of “dependent child.”[39] It did not matter if the man did not have a legal obligation to the child, was a casual romantic partner, had little or no income, or, in the case of Michigan law, was simply a boarder.[40]

As with “suitable home” rules, these policies often targeted Black mothers or arose in areas where Black people were likely to live. In Dallas County, Alabama between 1964 and 1967, all but four of the 186 families cut off due to this policy were Black.[41] Georgia’s 1952 ADC policy package, which included a similar “substitute father” provision, constrained the growth of Black families on the state’s ADC caseload for several years.[42] Several states and localities created special surveillance units to watch the ADC/AFDC home and conduct unannounced home searches, sometimes called “midnight raids,” looking for evidence of a cohabitating man. Jurisdictions with these surveillance units included many with high concentrations of Black people.[43] ADC/AFDC agencies often cut off families with tenuous evidence the man was a romantic partner or had the resources to provide for the children.[44]

In the early and mid-20th century, policymakers not only attempted to police Black women’s family status and romantic behavior but also to control their reproduction through sterilization. By the 1920s, the pseudoscience of eugenics advocated curtailing the birthrates of “unfit” persons including Black women through methods such as sterilization and marriage restrictions like miscegenation laws.[45] Although eugenics fell out of favor by the 1940s, the pathologizing of Black motherhood and resulting coercive control of Black reproduction persisted.[46] In fact, some policymakers’ arguments for reproductive control measures in cash assistance reflected eugenic arguments for population control as a means to save costs on public programs.[47]

In the late 1950s and 1960s, legislators in several states proposed mandatory sterilization laws for AFDC recipients. In Mississippi in 1958, state Rep. David H. Glass introduced a bill to “discourage immorality” that would have allowed the court to order sterilization for women who give birth to a “second or subsequent illegitimate child.”[48] Policymakers in Illinois, Iowa, Ohio, Virginia, and Tennessee considered similar proposals for compulsory sterilization of mothers receiving AFDC benefits who have children while unmarried.[49] Proponents of these bills used racist stereotypes and cost-cutting as justification for these bills: “The [Black] woman, because of child welfare assistance, [is] making it a business, in some cases of giving birth to illegitimate children,” Glass said.[50]

A Mississippi House bill introduced in 1964 called for the imprisonment or sterilization of a person who had more than one child outside of marriage. Some supported the bill because they believed “illegitimate” births were the direct cause of growing ADC costs. A pamphlet from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee detailed the racist nature of the bill: backers used data on “illegitimate” births by race to argue for the restrictions, with one lawmaker reportedly saying, “When the cutting starts, they’ll head for Chicago.”[51] The bill passed, without the sterilization clause but with a provision criminalizing the birthing parent for having an “illegitimate” child (joining Louisiana in criminalizing the act of giving birth when not married), punishable by 30 to 90 days in jail.[52]

Although none of these sterilization proposals passed into law, individual doctors supported their enforcement outside the formal AFDC system. In 1972 obstetrician Clovis H. Pierce — the only obstetrician in Aiken County, South Carolina — sterilized 18 mothers receiving AFDC at the county hospital; 16 were Black.[53] Sterilization for women in programs beyond AFDC was also common. A 1973 class action lawsuit banned the use of federal funds for sterilizations.[54] The suit found that approximately 100,000 to 150,000 women were sterilized per year under federally funded programs — almost half were Black, while most received Medicaid.[55]

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), later renamed the Department of Health and Human Services, had long been concerned about states denying access to Black families and families with unmarried mothers, but it wasn’t until the early 1960s that it began taking a firm stance. In response to Louisiana’s denial of AFDC support to thousands of Black children, HEW in 1960 issued an administrative rule (known as the Flemming rule after HEW head Arthur Flemming) that states could not ignore the needs of the child if the home was determined to be “unsuitable”;[56] state AFDC agencies had to help make the home suitable or move the child to more suitable living conditions, or risk loss of federal funding.[57] This was HEW’s firmest rule to date; by itself it improved access for Black and unwed mothers. But while the offending states complied with the rule on their “suitable home” policies, other policies including “man in the house” and farm policies that restricted access to cash assistance during planting and harvest seasons still prevented significant access to Black and unwed mothers.[58]

Lawyers for the welfare rights movement litigated for greater enforcement of federal eligibility standards and won key Supreme Court cases that ended some of the most harmful state eligibility rules discriminating against Black families and precluded states from restricting eligibility in various ways. The Court’s 1968 ruling in King v. Smith, for example, struck down Alabama’s “substitute father” policy and eliminated other “man in the house” rules; it also barred states from instituting additional eligibility rules, thereby shifting the power to determine eligibility restrictions from the states to the federal government. And in Goldberg v. Kelly (1970), the Court ruled that AFDC recipients had a right to a hearing before their benefits were terminated, among other due process measures. The National Welfare Rights Organization then pushed for enforcement of these protections when some states resisted changing their policies.

The Supreme Court rulings effectively ended many states’ arbitrary eligibility policies and processes and barred states from adding work or behavioral requirements or eligibility policies that were more restrictive than federal law. The 1960s and ’70s saw dramatic increases in the AFDC program as more families could access and maintain benefits.

Broad State Control Returns, and With It Reproductive Control and Behavioral Requirements

By the start of the 1980s, both Republican and Democratic policymakers claimed that AFDC encouraged dependency and undermined family values and recipients’ work ethic. Influential conservatives such as Charles Murray employed a “culture of poverty” philosophy and anti-Black narratives to call for major changes in AFDC. The media continued to racialize AFDC as a backdrop to debates surrounding “welfare reform”; in the 1980s and 1990s it elevated the “welfare queen” stereotype, popularized by President Reagan, furthering the idea of “unfit” Black mothers.[59]

Federal and state policymakers turned these racist ideas into policy. The federalization of AFDC began eroding in the late 1980s and early 1990s when states began to apply for, and the federal government began to approve, waivers from federal rules (available under section 1115 of the Social Security Act). States sought to impose new restrictions such as time limits, increased work requirements, and new behavioral requirements. In 1996 President Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Participation Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), the law that created TANF and reestablished broad state control. Along with work requirements, states implemented a wide range of behavioral requirements. Like mothers’ pensions and ADC/AFDC programs, state agencies could limit or completely cut benefits if families failed to meet these new standards.

Reproductive Control: Birth Control and Family Caps

Proposals to curtail Black and other AFDC mothers’ reproduction continued through the end of the 20th century, shifting from a focus on sterilization to a focus on birth control. In the early 1990s, lawmakers in several states proposed tying AFDC benefits to the new, long-acting implanted contraceptive Norplant. In 1991 Kansas state Rep. Kerry Patrick introduced legislation for financial bonuses for AFDC recipients if they implanted Norplant.[60] Echoing eugenic arguments of reducing costs by limiting certain people’s reproduction, Patrick said Norplant had “the potential to save the taxpayers millions of their hard-earned dollars.”[61] Louisiana Representative and Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke also proposed a Norplant bonus for AFDC recipients, following a campaign promise to reduce births by unmarried Black mothers.[62]

In some states, legislators took more coercive approaches to AFDC recipients and contraception. In 1993 Maryland Governor William Donald Schaefer suggested making Norplant mandatory for women receiving AFDC benefits. Bills in Mississippi and South Carolina would have required mothers to implant Norplant to get future benefits. In other states, bills would have denied benefit increases to mothers who declined the device.[63]

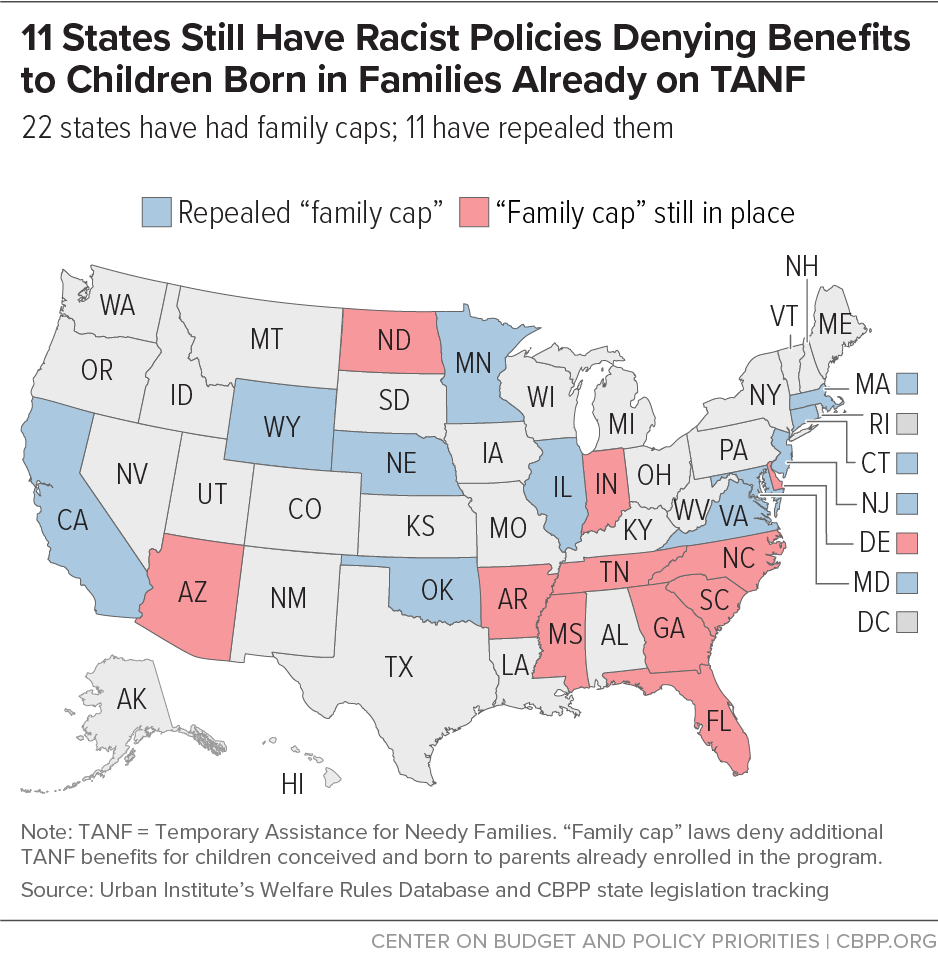

While the Norplant proposals did not pass,[64] states developed alternative measures to punish mothers’ reproductive decisions. In 1992 New Jersey became the first state to pass a “family cap” law, which denied an increase in cash assistance to families who have another child while enrolled in the program. The family cap was designed to discourage mothers receiving cash assistance from having additional children and was based on the erroneous and racist assumption that women have additional children in order to receive more benefits. Yet research finds that family caps have no impact on birthrates.[65] The family cap was included in Republicans’ 1994 “Contract with America” and in several bills that preceded PRWORA.[66]

In the debate over the creation of TANF, Congress members argued for the family cap by claiming that AFDC “promote[d] self-destructive behavior and illegitimacy,” recalling racist and sexist stereotypes of Black mothers as irresponsible and promiscuous.[67] One bill would have distributed the money saved by a family cap for states to create group homes for unmarried mothers and orphanages for their children, the implication being that such settings were more suitable for children than their own homes.[68] Although PRWORA did not require states to implement a family cap, 22 states had implemented them by 2001.[69]

States’ statutory language of family caps is race neutral, but early arguments in favor of the caps were not. In spearheading his state’s efforts for the family cap and other AFDC waiver policies, New Jersey Assembly Member Wayne Bryant wrote in a 1995 Washington Post op-ed that Black people were disproportionately receiving AFDC and not being “productive members of society.” Ignoring the systemic discrimination behind poverty in Black communities, Bryant, who is also Black, asked, “If parents are so irresponsible that they are unwilling to come to work or go to school, what makes you think they’re taking the added welfare dollars and spending them responsibly on their kids?”[70]

Fortunately, since the early 2000s more and more states have repealed their family cap laws; Connecticut is the most recent. But 11 states — many in the South — still have these laws on the books.[71] (See Figure 2.)

TANF Behavioral Requirements and Eligibility Exclusions

Today policymakers often conceptualize who “deserves” assistance in relation to employment, but also to certain other behavioral requirements that reinforce false, anti-Black narratives of irresponsible mothers and criminality. These policies, many of which began under AFDC’s waiver authority in the late 1980s and early 1990s and continue under TANF, deny assistance to families that need help and strip women of their dignity.

- Education-related rules. In 1987 Wisconsin initiated the first “learnfare” policy, which attempted to reduce teenagers’ truancy and drop-out rates by tying them to families’ benefits. Other states such as Ohio, Maryland, and Virginia implemented their own programs. However, analyses of different approaches to learnfare did not show that taking benefits away from families helped keeps students in school. In Wisconsin, a 1996 audit of learnfare, which simply reduced benefits when children were truant or dropped out, found it did not improve school attendance. Ohio’s learnfare program targeted older students and provided cash incentives and penalties if the student stayed in school or not. A Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation assessment found it was successful in encouraging students to complete high school or get their GED but had less success in getting those who dropped out back in school.[72] In 2019 (the last year for which comprehensive data are available) learnfare policies were still in effect in 37 states, including Wisconsin.[73]

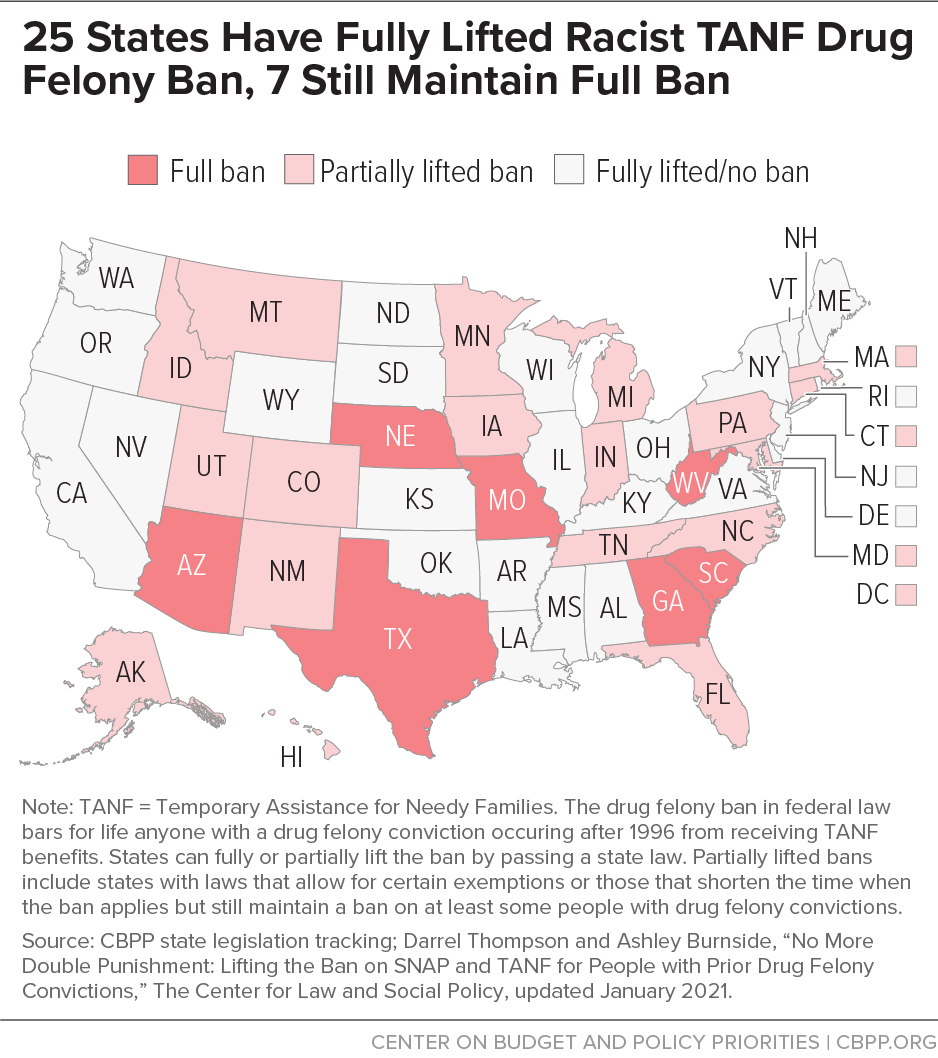

- Drug felony ban and drug testing. In the 1980s the federal government began restricting certain federal benefits for people convicted of drug-related crimes as part of its “war on drugs,” which targeted Black and brown communities.[74] Such policies are based on people’s past conduct, not current need: eligibility for programs like TANF has been shown to reduce recidivism.[75] And they ignore inequities in the criminal justice system, where Black people are much more likely to be arrested or incarcerated for drug-related offenses despite using and selling drugs at similar rates as white people.[76] The 1996 federal TANF law bans people with felony drug convictions from receiving TANF benefits, but it allows states to opt out of or modify the policy via state legislation. The number of states with a full lifetime TANF ban on people with drug felony convictions has dropped from 23 states and D.C. in 1999[77] to seven states in 2020. (See Figure 3.) Twenty-five states have eliminated the ban entirely.[78]

Additionally, the 1996 TANF law gave states the option to require drug tests as a condition of receiving benefits, presuming participants’ guilt and invoking racist stereotypes of Black people as criminals and drug users, when again people of different racial groups use drugs at roughly equal rates.[79] Most TANF recipients do not abuse drugs, research shows, and the requirements are very costly to administer.[80] Although mandatory “suspicionless” testing has been challenged and found unconstitutional in the courts in Michigan and Florida,[81] a number of states have introduced and passed suspicion-based drug testing laws; 13 states currently have drug testing policies for TANF applicants and recipients.[82] Drug testing policies rarely find people who test positive but reduce TANF caseloads by creating barriers for applicants to become eligible. And like the felony bans, the policies cut off assistance for those who might stand to benefit most from cash assistance.

- Restrictions on Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards. Public officials have long had unfounded concerns about mothers mismanaging cash aid or abusing resources under the assumption these mothers won’t want what’s best for their families.[83] Today’s EBT card restrictions in TANF programs also presume that parents will not use their benefits for their families’ needs despite evidence that families receiving public benefit mainly spend their resources on housing, food, and transportation.[84] For example, in the case of the American Rescue Plan’s expansion of the Child Tax Credit, 91 percent of families with incomes under $35,000 spent some or all of their monthly payments on necessities.[85] In 2012 Congress passed restrictions on EBT cards, requiring that states limit purchases at certain locations such as casinos, liquor stores, and strip clubs.[86] Although the federal law did not require state policymakers to pass legislation, many did and some included restrictions beyond federal statute. At least 25 states had EBT card restrictions in 2019.[87] A miniscule fraction of EBT card use is at bars and adult entertainment venues, although media reports tend to sensationalize the issue based on this very small number of transactions.[88] With little evidence that TANF families are using their EBT cards in these venues, these restrictions are a solution in search of a problem. And they can be traced back to the same harmful and erroneous assumptions of lack of impulse control that arbitrarily restricted Black women’s historical participation in cash assistance programs.

Cash assistance for when families experience a crisis needs to be a critical component of our economic support system. TANF, with its history of anti-Black racism, must be fundamentally reformed by adopting a Black Women’s Best framework. Black mothers need a cash program that provides stability through life’s challenges, affirms their autonomy, and protects their children from hardship. When TANF works for Black mothers, it will mean that we have a program that benefits all families facing significant economic distress. That starts with undoing policies that are based on racist ideas and that have historically harmed Black families.

This work cannot be left entirely to the states; federal changes are essential to advance racial equity nationally and ensure a stable economic foundation for all families. For a reimagined TANF program, we envision:

- Barring behavioral requirements and other eligibility exclusions. Rooted in racism and sexism, these provisions demean families by assuming that adults are irresponsible and do not want what is best for their families. Worse, they often take away assistance from families who need it. Some also disproportionally hurt Black women and Black families. Eliminating them would remove the concept of “deservingness” from a program that should be designed to support parents and protect children from destitution, for everyone who needs this assistance.

- Refocusing TANF agencies on helping families address immediate crises and improving long-term well-being. TANF is better suited than other economic security programs to provide the support parents need to achieve the goals they set for themselves and their families. (For example, tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit or the Child Tax Credit cannot provide services to families.) Yet TANF must do a much better job of helping families in crisis address their immediate needs and setting them up for long-term stability. The program should move away from its long history of making broad judgments about what’s best for families, and toward voluntary support programs that align with each family’s goals and needs. Making TANF services voluntary would put the burden on TANF programs to provide assistance — including education, training, and job placement services — that recipients evaluate to be positive and of benefit to their families, whatever their circumstances may be. For example, in a reimagined TANF program, staff could act as skilled coaches and “navigators” instead of focusing on compliance with paternalistic policies. Through a practice known as family-centered coaching, staff could help participants explore challenges and opportunities and develop solutions to address their personal and family goals in a time frame that works for them.[89] States should also connect families to trauma-informed services that center the needs and goals of families.

- States taking action now to eliminate punitive policies around behavioral requirements and reproductive controls. Change at the federal level could take years, but states should not wait for federal action to affirm the dignity and autonomy of parents. They can eliminate punitive policies now that make eligibility contingent on past conduct rather than current need, that control families’ reproductive decisions, and that coerce behaviors. For example, states can fully opt out of the drug felony ban, a relic of the racist war on drugs; end drug testing for applicants, which evidence shows reduces participation among those who would not test positive; repeal family caps, another policy based on racist stereotypes; and stop learnfare, which cuts people off benefits despite being of questionable educational benefit to students.