Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the nation’s primary program for providing cash assistance to families with children when parents can’t work or have very low income, has a vital role to play in helping families meet their basic needs, avoid economic instability and its negative impacts, and obtain other resources that can help provide a foundation for improving their circumstances. But TANF falls far short of what it should be. It reaches few families in need and provides inadequate cash aid and other assistance to help families resolve crises and improve their well-being. TANF’s shortcomings flow directly from the fact that its history is steeped in racist assumptions about work ethic and deservingness that particularly strip Black women of their dignity. This racist legacy is a major reason why TANF cash assistance, though a critical support for some, doesn’t meet the needs of most families regardless of their race or ethnicity, and serves Black families particularly poorly.

This paper — part of a series on TANF and race examining how racist and sexist attitudes towards Black women have helped shape the history and design of cash assistance programs since the early 20th century[1] — presents policy recommendations to improve TANF that follow the “Black Women Best” (BWB) framework. Janelle Jones, now Chief Economist at the Department of Labor, developed the BWB framework, which “argues if Black women — who, since our nation’s founding, have been among the most excluded and exploited by the rules that structure our society — can one day thrive in the economy, then it must finally be working for everyone.” [2]

Cash assistance for when families experience a crisis or a change in circumstances is a critical component of our economic support system. TANF must be fundamentally reimagined as a cash program that provides families with stability through life’s challenges, protects their children from hardship, and affirms and supports their autonomy over their families and careers. TANF should promote connections to supportive services and work and training opportunities for parents on a voluntary basis; eligibility for cash should be based on financial need and should not be contingent on work or behavioral requirements.

Any significant effort to improve TANF requires acknowledging and changing the racially driven attitudes and beliefs upon which TANF is built, which have contributed to TANF’s ineffectiveness as a safety net for all parents and children struggling to make ends meet. Recognizing the ways in which racist views of Black women have influenced the basic design of the current TANF program is the first step to redesigning TANF with antiracist policies that, in turn, would establish a cash assistance program that works better for all families with the lowest income. All children, but especially Black and brown children, need a strong set of antiracist economic support policies for their long-term well-being.

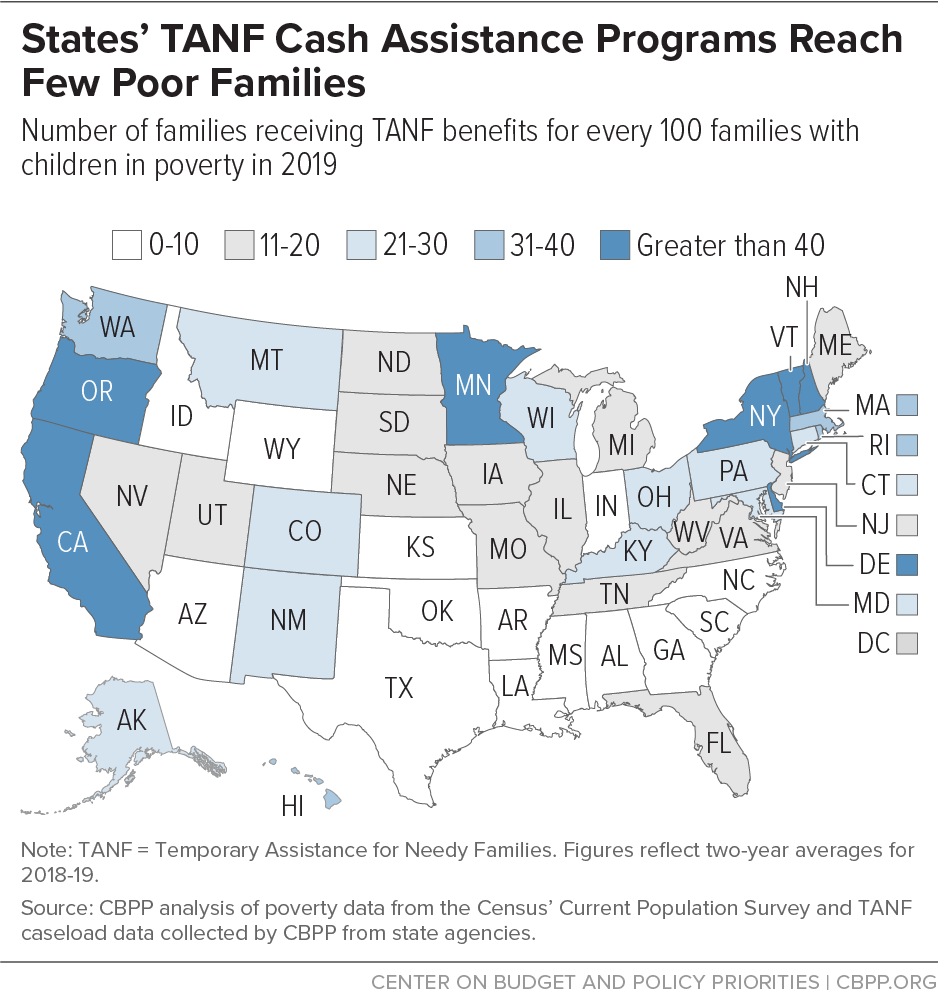

The central goal of an antiracist agenda for TANF should be to provide adequate stability to families that have low or no income or experience a crisis, and to do so in a manner that affirms rather than undermines their dignity. This means TANF must do a much better job of reaching children living in poverty with cash assistance and providing adequate benefits to those it serves. If TANF had the same reach that its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), had in its final year (1996), some 2 million more families nationwide would have received cash assistance in 2019.[3] In 2019, for every 100 families in poverty, only 23 received cash assistance from TANF — down from 68 families in 1996. Of special note, Black children are likelier to live in the 14 states that perform especially poorly, reaching 10 or fewer of 100 families in poverty. (See Figure 1.) Most of these states had weak AFDC programs that provided low benefits and reached a small number of children in need and their cash assistance programs under TANF have worsened significantly.

There are multiple reasons for TANF’s declining reach. The leeway that TANF gives states to impose eligibility restrictions, to make it hard to apply and enroll in TANF, and to take benefits away from people who don’t meet various requirements plays a significant role. The structure of the TANF block grant, the design of the federal work rates, and states’ ability to use TANF funds for other state budget purposes created incentives for states to impose even more punitive policies than those in the federal statute. Examples include the imposition of work requirements on families before their applications for assistance are approved, “family caps” that deny assistance to children born after a family’s initial benefit receipt, and time limits as short as 12 months. States have used policies like these to reduce their TANF caseloads, generating savings they can then divert to other uses, including supplanting funds they would have spent in various areas.

Every state can and should take steps now to bring antiracist reforms to its TANF program. States can use their flexibility under TANF to offer more assistance to more families with little income. They can end policies that exclude families from aid and can direct more of their TANF funding to cash assistance by raising benefit levels and improving program access. They can inform recipients about resources available in their communities and help them gain access to human services, work, education, and training programs that can improve their well-being over the long term. Some states are taking steps in this direction — increasing benefit levels, ending sanction policies that take all TANF benefits away from a family when a parent doesn’t meet a work requirement, and creating coaching programs that help recipients set personal goals and provide support as they work to achieve them.

However, federal action is also essential to ensure that TANF meets the needs of families in all states and to advance racial equity nationally. Black children disproportionately live in the states whose programs have the lowest benefits and reach the fewest families in need.[4] And Black women are far more likely than white women to lose TANF due to sanctions after caseworkers decide they didn’t meet a program rule.[5] By leaving nearly every policy decision to the states, TANF perpetuates a pattern of leaving Black families behind and disproportionately excluding and depriving Black mothers of the help they need to provide stability for their families when they hit hard times. And the states that leave Black families furthest behind are the least likely to change their policies in the absence of federal requirements and prohibitions.

The recommendations outlined in the rest of this report, which primarily focus on federal law or administrative changes, include:

- Establishing a federal minimum benefit so that no family falls below a certain income level.

- Ending mandatory work requirements.

- Barring behavioral requirements, time limits, and other eligibility exclusions.

- Refocusing TANF agencies on helping families address immediate crises and improving long-term well-being.

- Changing TANF’s funding structure to strengthen basic assistance, address funding inequities, and prevent erosion over time.

Federal law should require states to meet minimum levels for TANF benefit amounts. Currently, benefits are at or below 60 percent of the poverty line in every state and below 20 percent of the poverty line in one-third of states, including nearly all Southern states.[6] Benefits are simply too small to meet families’ basic needs or maintain their financial stability, which is crucial both for children’s daily life and for their futures. Studies show that income matters for children’s long-term well-being; financial stability gives them a better chance of growing up healthy and with an opportunity to thrive.[7] TANF does far less than it could to help families — especially Black families, who are more likely to live in states that serve relatively few poor families and have lower benefits — to weather crises and to stave off hardship, which can have long-term negative consequences for children.[8]

States have total flexibility to set benefit levels under TANF. They had this flexibility under AFDC, as federal policymakers, often led by congressional members from Southern states, repeatedly rebuffed efforts to require states to meet an AFDC benefit floor. In AFDC’s final two decades, states with higher Black populations had smaller average benefits than states with lower Black populations, researchers found.[9] Today as well, Southern states with higher Black populations and deep-seated legacies of slavery and Jim Crow remain among those with the lowest TANF benefits. [10] Over half (55 percent) of the nation’s Black children live in a state with TANF benefits at or below 20 percent of the poverty line, compared to 40 percent of white children.[11]

Moreover, states have failed to use their flexibility under TANF to reinvest most of the savings from declines in the number of people receiving cash assistance into improving (or even maintaining) the value of benefits for families that do receive benefits. Instead, states have diverted those savings to other budget areas, often to fund services they would otherwise have funded with state general funds. Despite recent benefit increases in a number of states, the value of cash benefits — low even when TANF began — has declined further under TANF in nearly all states. In 33 states, benefit levels have fallen by at least 20 percent in inflation-adjusted value since 1996. States spent only 21 percent of their TANF funds on basic assistance in 2019, compared to 71 percent in 1997.[12]

States’ longstanding and unfettered flexibility to set benefit levels has perpetuated policies that, while rooted in historical racism, do not just affect Black families; inadequate and shrinking benefits affect all families facing a crisis or struggling to pay for the basics. A federally mandated minimum benefit is needed.

End and Bar Mandatory Work Requirements

Conditioning benefits on participation in mandatory work programs is one of TANF’s most racially driven policies, arising from a long history of state control over Black labor starting with enslavement and other coerced labor practices that continued long beyond emancipation.

Studies have found that while mandatory work requirements initially led to modest increases in employment, those faded over time. Work requirements also led to increases in deep poverty (family income below half of the poverty line) among recipient families, many of which had their benefits reduced or taken away. [13] One study that examined 11 pilot programs — local forerunners of TANF’s work requirements — found that while most of them slightly improved short-term employment, deep poverty rates rose by a statistically significant amount in six of the 11 and didn’t fall significantly in any. Other research found that deep poverty rose among children in the decade after TANF’s creation, especially among Black and Latinx children.[14]

Moreover, the employment gains generally don’t translate into long-term improvement in employment and earnings for families. All states impose work requirements in TANF and require parents receiving TANF to participate in narrowly defined work activities. Those activities focus on immediate job placement. But as studies have found, this “work first” approach pushes participants toward the same low-paying, unstable jobs that led them to seek help from TANF in the first place.[15] If unable to meet the requirements, they face severe punishment in the form of sanctions that take away the cash benefits they rely on to pay their rent and utilities and put food on the table. In most states, the entire family can lose benefits, even the children. Some states go further by requiring applicants for assistance to complete upfront work requirements before approving their application.

The design of TANF’s work requirements (as well as other behavioral requirements discussed below) grew out of the racist trope that Black women are inherently lazy and need to be threatened with harsh punishment to work to support their families, even though Black women actually have worked at higher rates than white women throughout our nation’s history.[16] In addition to being ineffective in raising long-term employment earnings, the emphasis on immediate job placement perpetuates occupational segregation, pushing TANF recipients into low-paid jobs overwhelmingly held by Black women and other women of color.[17]

States’ application of work requirements has also exacerbated racial inequities. Research consistently shows that Black women are significantly more likely to have their TANF benefits taken away for not meeting work requirements than white women. [18]

While state decisions, not federal rules, determine work requirements for individual TANF recipients, federal TANF law requires states to meet a work participation rate that significantly influences state program designs. (A state’s work participation rate measures the share of work-eligible recipients that participate in work activities as defined in federal law for a specified number of hours per week and document every hour of participation.) To move TANF in an antiracist direction, federal policymakers should eliminate the work participation rate. They also should eliminate federal requirements that states impose sanctions and mandate participation in work activities. To ensure that states don’t maintain these policies even without a federal requirement, federal policymakers also should bar states from mandating work as a condition of eligibility for cash assistance and imposing sanctions for non-participation.

As discussed below, state and federal policymakers should adopt strategies that focus more on helping families to resolve crises and improving parents’ longer-term well-being, while ending the practice of taking away help that families need to ensure their children have a roof over their head, clothes to wear, and food on the table.

During AFDC’s final decades, proponents of radical changes in the program ignored structural changes in the economy and changing social norms that complicated the lives of Black mothers with low income.[19] Instead they repeatedly promoted narratives of Black mothers as lazy, irresponsible, and criminal and therefore needing paternalistic policies to coerce work and other “responsible” behaviors by threatening the loss of assistance. Federal and state TANF requirements and restrictions influenced by these narratives have contributed to caseload decline but also to the undignified nature of TANF. They include harsh policies that take assistance away from families when an adult doesn’t meet a behavior requirement, time limits on benefit receipt, and other exclusionary policies stemming from racist ideas about Black mothers.

- Behavioral requirements. State TANF programs are rife with requirements that deny or reduce benefits to a family based on the conduct or behavior of the parent. These include conditioning TANF receipt on children’s school attendance, requiring parents to undergo drug testing, restricting how or where cash TANF benefits can be spent, and requiring parents to enter into personal responsibility plans. These policies have a common and racist core: the assumption that a Black woman’s poverty is due to personal behavioral failings and that regulating her behavior is the solution.[20] They reflect a legacy of policies policing the conduct of mothers who receive cash aid. For example, caseworkers for the mothers’ pension programs of the early 20th century and AFDC routinely assessed mothers’ supervision of their children and care of their homes to encourage or discourage certain behaviors.[21] Caseworkers often applied stricter behavioral standards to families living in Black communities, making it easier to deny those families.[22]

- Eligibility exclusions. Some state and federal TANF policies exclude individuals from benefits based on their past conduct. One example is the federal lifetime exclusion of those with drug-related felony convictions, which disproportionally affects Black parents because of policing practices that target Black communities. Another is the family caps that still exist in 11 states, which deny benefits for a child conceived while the mother is receiving TANF and thereby impose a permanent penalty on the child. The family cap is an extension of previous reproductive controls such as “suitable home” requirements in some states’ AFDC programs, which denied benefits to mothers who failed to conform to certain sexual and parenting norms.[23] State policymakers maintained these policies, which often targeted Black women, until federal AFDC policy restricted their ability to do so.

-

Time limits. Time limits on receipt of aid were ushered in by racially coded language that cash aid should not be “a way of life.”[24] In the 1990s, first through AFDC waivers and then under the 1996 law creating TANF, the federal government allowed states to cut entire families off of benefits not because the family no longer qualified for or needed help, but simply because it had reached a time limit. While the TANF law limits federally funded benefits to 60 months, states can extend benefits for 20 percent of cases or use state TANF funds beyond 60 months. But instead, many states have set time limits shorter than 60 months — Arizona’s is just 12 months — and permit far fewer extensions than federal law allows.

Time limits disproportionately affect families of color. One reason is that states where Black and Latinx children are likelier to live are among those with the harshest time limit policies.[25] Other factors include racial bias in caseworker decision making, such as whether a given family’s circumstances qualify them for an extension of the time limit, and the greater barriers to employment that families of color face.[26]

Federal policymakers should undo any provisions mandating that states impose these requirements or exclusions. They also must bar states from imposing these types of conditions; otherwise, these policies will remain in effect in some states.

In addition to providing cash assistance to help families meet their basic needs, TANF has a role to play in helping families find resources to address other issues they may be facing, including stabilizing their housing, addressing physical and mental health issues, enrolling in a training or education program, or finding a job. For families seeking to improve their long-term well-being, TANF agencies can help them set personal goals and develop plans for achieving them, while also providing support to maximize their chances of success. But importantly, moving TANF programs in an antiracist direction means giving families the choice of whether to seek services in addition to cash assistance; eligibility for cash assistance should not be contingent on participating in other programs.

Cash assistance programs have a long history of making judgements about what is best for families rather than giving them the freedom to make those choices on their own. TANF’s predecessors focused on “rehabilitating”[27] mothers by urging certain behaviors even when their primary challenge was a lack of resources to meet their family’s basic needs. Caseworkers disproportionally denied access to Black and unmarried mothers if they didn’t meet the caseworkers’ standards.[28] This approach to services reinforced the idea that individual failings rather than systemic racism led to families’ struggles.

Under TANF, federal and state policy have followed a broadly similar approach, though more narrowly focused on requiring recipients to find employment as quickly as possible and limiting their participation in longer-term education and training programs that would prepare them for quality jobs. In most states, all TANF recipients are expected to participate in the same sequence of activities — usually starting with job search — even though their circumstances vary substantially. A family fleeing domestic violence has very different needs than a family in which the parent lost their job and expects to return to work as soon as they find a new one, or a family in which a parent wants to increase her education or skills before looking for her next job. Yet all are subject to the same requirements and the same time limits.

Making TANF services voluntary would put the burden on TANF programs to provide assistance that recipients will see as benefiting their families, whatever their circumstances may be. For example, in a reimagined TANF program, staff could act as skilled coaches and “navigators” instead of focusing on compliance with paternalistic policies. Through a practice known as family-centered coaching, staff could help participants explore challenges and opportunities and develop solutions to address their personal and family goals in a time frame that works for them.[29] And as navigators, staff could help families identify and access the full range of programs available in their local communities that align with their goals and needs. TANF recipients should have equal access to the same programs available to other families in their communities. And TANF agency resources previously used to monitor compliance with mandatory work and behavioral requirements could instead be used to help families in new and meaningful ways.

States spend few of their TANF dollars on meeting children’s basic needs. States spent just $6.5 billion of their federal and state TANF funds on basic assistance for families struggling to make ends meet in 2019, down from $14 billion in 1997, TANF’s first full year of implementation. That amounts to a 71 percent decrease in state and federal TANF funding going toward basic assistance, when adjusting for inflation.[30] Here, too, TANF policy failures especially hurt people of color: Black and Latinx children disproportionately live in the states that spend the smallest shares of their TANF funds on helping families meet their basic needs.[31]

During the “welfare reform” debates that led to TANF’s creation, proponents of converting AFDC to a block grant argued that states needed flexibility to shift the money they’d save by reducing cash assistance caseloads into programs supporting work. But under TANF, states spend little on connecting families to work activities and providing work supports; indeed, what they do spend is often not targeted to families with the lowest incomes. Additionally, a significant and growing share of state and federal TANF funds have been diverted to other areas of state budgets, such as pre-kindergarten and child welfare services. While these are important investments, states should use funding sources other than TANF, especially since so few TANF funds are spent on basic assistance.

Accordingly, federal policymakers should require that states direct more TANF funds to cash assistance. Specifically, they should require states to spend at least half of their state and federal TANF funds on cash assistance to help families in poverty meet their basic needs. Setting a benchmark would further two goals, ensuring both that more families with very low incomes have meaningful access to cash assistance and that families receiving TANF have sufficient assistance to help them meet basic needs. These goals will not be met without such a mandate, particularly given the incentives and temptations for states to reduce caseloads and spend the funds elsewhere.

At a minimum, making two other changes to TANF funding would also further the goals of providing meaningful access and adequate benefits.

- First, policymakers should restore funding to its original value and prevent it from eroding in the future. The federal government gives states a fixed block grant totaling $16.5 billion each year; this amount has never been adjusted for inflation and now is worth about 40 percent less than when TANF was created. If the block grant had been adjusted for inflation, it would be about $27.7 billion for 2021. Policymakers should restore this roughly $11 billion to annual TANF funding and adjust for inflation going forward.

- Second, policymakers should reshape TANF’s allocation formula for states by allocating funding more equitably and in proportion to each state’s share of the nation’s children in poverty. Some states receive very low funding relative to need in their state. TANF’s original block grant allocation structure was based on state AFDC spending amounts; the states where Black children disproportionately live generally had lower AFDC benefits, so the TANF block grant formula locked in those lower TANF funding levels per poor child. Some 23 percent of the nation’s Black children live in the six states with the lowest TANF block grant amounts per poor child, compared to 13 percent of white children.[32] The block grant distribution was inequitable at the outset and has become more inequitable over time.[33] To address this problem, states with more families in need should receive more resources.