Economic security programs can help families meet basic needs and improve their lives, but design features influenced by anti-Black racism and sexism have created an inadequate system of support that particularly harms Black families and other families of color. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the nation’s primary program for providing cash assistance to families with children when parents are out of work or have very low income, is perhaps the clearest example of a program whose history is steeped in racist ideas and policies (see text box, “Defining Key Terms,” for definitions) that particularly strip Black women of their dignity.

This paper, the first in a series on TANF and race, documents more than a century of false and harmful narratives — such as that Black women are unfit mothers — and paternalistic policies that sought to control Black women’s behavior and compel their labor. It then shows how these ideas and policies still influence TANF today. (It does not cover the full scope of TANF policies that are racist and should be changed, including child support enforcement requirements that apply to custodial parents and exclusions of immigrants.) This legacy of exclusion and subjugation is a major reason why TANF cash assistance, though a critical support for some, doesn’t meet the needs of most families in poverty, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

TANF does not refer explicitly to participants’ race or ethnicity, but historical racism and contemporary patterns of racial discrimination and bias affect who has access to cash assistance. Below we define terms used in this report to describe policies that work either to uphold or to eliminate racism, a system of oppression based on race.

Antiracist policy: any policy that promotes or maintains racial equality, including by reversing racist policies and their effects. Antiracism as a broader philosophy recognizes racist policies, not just racist ideas, as a root of racial inequality.

Racist idea: any idea that regards one racial or ethnic group as inferior or superior to another in any way. Racist ideas are created to justify and sustain racist policy.

Racist policy: any policy or practice, written or unwritten, that creates or maintains racial disparities in access to public assistance, housing, goods and services, opportunity, and well-being.

White supremacy: “The idea (ideology) that white people and the ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions of white people are superior to People of Color and their ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions. . . . [W]hite supremacy is] ever present in our institutional and cultural assumptions that assign value.”

The “Black Women Best” (BWB) framework[2] developed by Janelle Jones, now Chief Economist at the Department of Labor, “argues if Black women — who, since our nation’s founding, have been among the most excluded and exploited by the rules that structure our society — can one day thrive in the economy, then it must finally be working for everyone.”[3] Consistent with Jones’ framework, redesigning TANF so that it centers the needs of Black women and families, adequately helps families struggling to afford the basics, and offers meaningful opportunities to gain skills and secure quality jobs would better serve families of all races and ethnicities, improving child outcomes and reducing hardship.

Federal policymakers created TANF in 1996 with the purported promise of helping families lift themselves out of poverty through work. But much of the debate around the 1996 law was centered (often implicitly, but sometimes explicitly) on Black mothers,[4] who were portrayed as needing a “stick” to compel them to be more responsible and leave the program. TANF’s harsh work requirements and arbitrary time limits disproportionally cut off Black and other families of color. Also, Black children are more likely than white children to live in states where benefits are the lowest and where the program reaches the fewest families in poverty. In the decade after policymakers remade the cash assistance system, it became much less effective at protecting children from deep poverty — that is, at lifting their incomes above half of the poverty line — and children’s deep poverty rose, particularly among Black and Latinx children.[5]

Many of TANF’s rules mirror those dating back to cash programs of the early 20th century, and many of its assumptions reflect anti-Black racism dating back to enslavement. Throughout the history of cash assistance, many policymakers and public figures have used these same racist justifications and stereotypes to question Black women’s reproductive choices, coerce Black women to work in exploitative conditions, and control, deride, and punish Black women who receive cash assistance. TANF’s design perpetuated these attitudes and, in some ways, reinforced them, such as through stricter work requirements and expanded state control over program rules.

Briefly summarized, this paper shows that:

Slavery and Jim Crow laid the foundation for the economic, reproductive, and behavioral control policies that have permeated later cash assistance programs, including TANF. Labeling Black people as biologically inferior to white people and inherently lazy, promiscuous, irrational, and resilient to pain, white enslavers employed forced reproduction and labor to exploit, control, and punish enslaved Black women while maximizing their economic returns. Even after emancipation, white policymakers and employers continued to control when and where many Black people worked. White landowners’ system of sharecropping trapped Black people in debt, which their meager earnings could rarely pay off. Vagrancy laws and other policies criminalized Black people and forced many of them into involuntary servitude and other forms of exploitative work.

The idea that only some families “deserve” cash assistance is evident in mothers’ pensions of the early 20th century, which predated federal aid programs created in the New Deal. These state and local programs aimed to enable children to be cared for in their homes if their families lost a male breadwinner due to death, abandonment, or poor health. The original proponents of mothers’ pension programs made clear that a child’s deservingness for aid depended on the mother’s character; to state and local program administrators, that often meant aiding white children of widowed mothers, not children of unwed or Black mothers. Federal policymakers designing later cash assistance programs preserved much of states’ and localities’ discretion over mothers’ pension programs.

States’ control over the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program, created in 1935, enabled them to exclude many Black and brown people. ADC (renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children or AFDC in 1962) provided federal funding to states to assist children who lived with a single mother. Southern members of Congress insisted that state and local officials control ADC eligibility and benefit levels, which enabled them to preserve an economic system that relied on the low-wage labor of Black workers in the South and Latinx workers in the Southwest.

The large majority of Black working women were excluded from other New Deal social programs like unemployment insurance and Old Age Insurance (now known as Social Security) because they were either domestic or agricultural workers, and many fell deeper into poverty during the Great Depression. Similarly, the new ADC program did little for Black families as they made up a small share of the ADC caseload, especially in the South. Many Southern states denied Black families access to ADC because they did not want to “interfere with local labor conditions.”

As ADC rolls grew and diversified in the 1940s and 1950s, a number of states imposed punitive policies to control mothers, disproportionally harming Black families. Starting in the 1940s, some states passed conduct- or morals-based eligibility policies such as so-called “man-in-the-house” or “suitable home” policies. States targeted the new laws at Black and unmarried mothers and their children. For example, in the first three months after Louisiana barred children from receiving ADC if their mothers were deemed “unsuitable” because of sexual activity outside marriage, 95 percent of the 6,000 children cut off were Black.

In addition, many state policymakers focused on Black women’s work and work ethic, even though Black women have historically had higher work rates than white women. Some states passed “farm policies” cutting off ADC benefits during planting and harvest seasons to coerce Black parents to work in agriculture even if no paying jobs were available. These issues were not confined to the South: some policymakers in the North denounced Black migrants moving to their cities, who they claimed were unwilling to work and only seeking more generous ADC benefits.

Despite greater enforcement of federal protections for AFDC eligibility, harmful narratives about Black single mothers began driving debates over cash assistance in the 1960s and 1970s. In a positive development, federalization of some AFDC eligibility rules enabled significant gains in ensuring basic rights for those applying for or receiving aid during these decades. However, there was a growing backlash against the rising number of Black and brown families on AFDC and against Black social movements elevating the issue of Black poverty. In the 1960s and 1970s, increasingly negative media coverage about waste, fraud, or abuse in public assistance programs — stories often illustrated with photos of Black people — fed into stereotypes of Black single mothers as irresponsibly refusing to work and having large numbers of children to receive cash assistance. A controversial report on Black families by Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan reinforced these narratives about Black single mothers, as did speeches by presidential candidate Ronald Reagan attacking “welfare queens.”

The spread of these narratives contributed to weakened public support for AFDC and led many federal policymakers to begin moving away from the idea that AFDC mothers’ primary responsibility should be caring for their children in the home. The federal government took the first steps toward the work requirements that we see today in TANF by enacting the Work Incentive Program in 1968.

The end of the century brought a return to greater state control over cash assistance and an emphasis on “personal responsibility.” Racist narratives about Black women from the media and public figures continued to be the backdrop during the “welfare reform” debates of the 1980s and 1990s. Conservative scholars charged that AFDC and other government assistance reinforced a “culture of poverty,” especially within Black communities; the frameworks they proposed to address poverty centered work, regardless of whether jobs were available or if they paid a wage to lift families out of poverty.

Starting in the early 1980s, AFDC went through a series of changes. First, the Reagan Administration pushed through major cuts to the program. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the federal government issued waivers granting states flexibility to experiment with changes in their AFDC programs; use of the waivers expanded significantly in the early 1990s under the Clinton Administration. Often using racist dog whistles like promoting “personal responsibility,” state policymakers imposed new requirements and restrictions such as time limits, increased work requirements, and family caps (which punished families by limiting additional benefits if a mother had another child while receiving AFDC benefits).

Bill Clinton, who campaigned for the presidency promising to “end welfare as we know it,” and House Republicans led by Speaker Newt Gingrich, who talked about reestablishing orphanages in the context of “welfare reform,” called for even more dramatic changes. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which Clinton signed in August 1996 after vetoing two previous bills, replaced AFDC with the TANF block grant, wiping out federal eligibility rules and ending families’ entitlement (or individual right) to cash assistance. TANF includes harsh work requirements and grants states significant control over how to spend their fixed TANF resources; both of these design features give states strong incentives to make it hard for families to access aid and easy for families to lose assistance if they are able to get into the program.

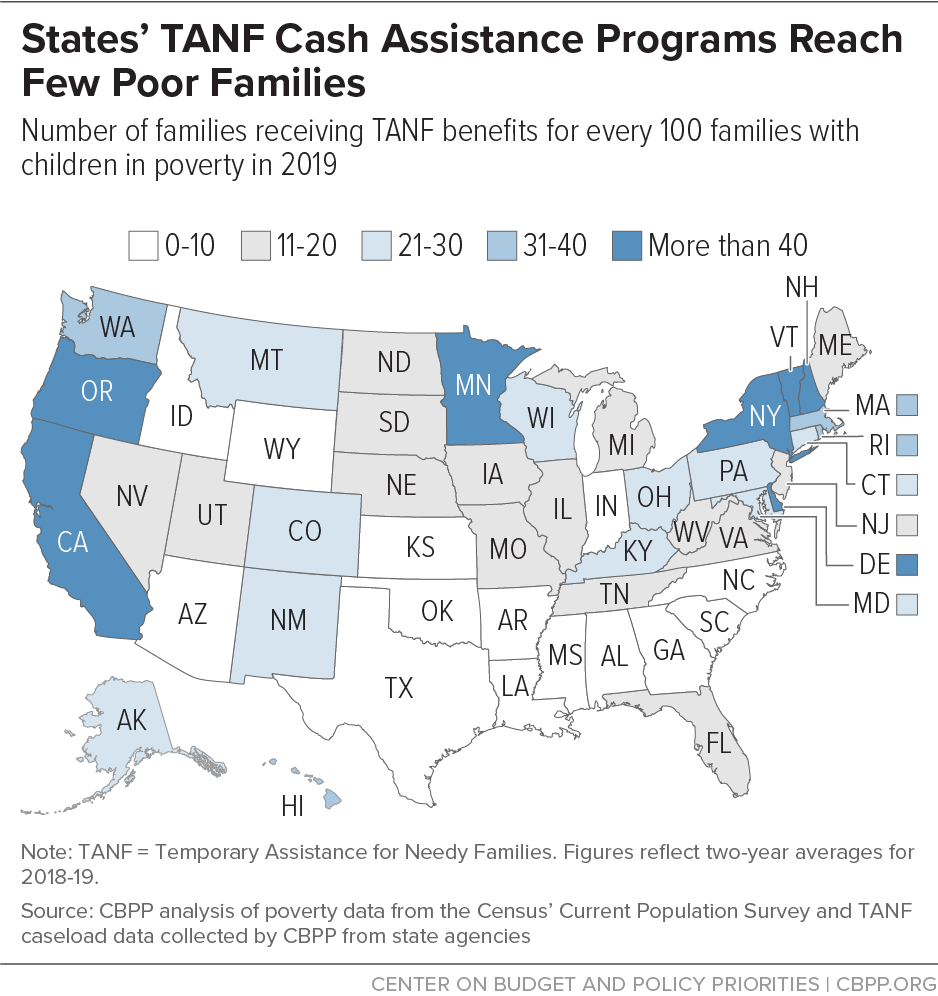

TANF’s embedded racism and unfettered state control have led to a deteriorating cash assistance program for all families, with Black families facing a disproportionate impact. A quarter century after federal and state policymakers created and implemented TANF, an already low-benefit program has diminished further in generosity and reach, leaving millions of families with children with no regular source of income to meet their basic needs when they cannot work. In 1996, 68 families with children received benefits for every 100 families in poverty; by 2019, that figure had dropped to 23, and in 14 states it was 10 or less. (See Figure 1.) Black children have the greatest likelihood of living in states with the lowest benefits and with programs that reach the fewest families in need.[6]

TANF policies have done more to limit access to the program than to help parents find quality jobs, and they have disproportionately affected Black and brown women, who are far more likely than white women to lose benefits because they were sanctioned for not meeting a program rule or reached a time limit. TANF behavioral and work requirements have reduced access to income assistance and reinforced negative messages about parents, particularly Black parents; they have done little to help parents improve their employment prospects. Most parents end up returning to the unstable, low-paid jobs that led them to TANF in the first place. And while TANF proponents claimed states would use the savings from TANF caseload declines to invest more in work programs and work supports, states instead have redirected much of those savings to fund other services in ways that often supplant state investment.

Centering the needs of Black mothers and children would improve the well-being and economic security of all families with children. A redesigned TANF cash assistance program has a role to play to support families when they fall on hard times. Recognizing the ways in which racist views of Black women have influenced the basic design of the current TANF program is the first step to redesigning TANF with antiracist policies. Such a redesign in turn, would establish a cash assistance program that works better for all families with the lowest incomes, just as posited in the Black Women’s Best framework. A redesigned TANF system would include policies that support families and help expand opportunity, including:

- Establishing a federal minimum benefit so that no family falls below a certain income level.

- Ending and barring mandatory work requirements.

- Barring behavioral requirements, time limits, and other eligibility exclusions.

- Refocusing TANF agencies on helping families address immediate crises and improving long-term well-being.

- Changing TANF’s funding structure to strengthen basic assistance, address funding inequities, and prevent erosion over time.

Enslavement and Jim Crow: Beginnings of Reproductive, Economic, Behavioral Control

Attempts to control Black women’s reproduction, work, and other behaviors started with enslavement and continued under the Jim Crow laws of the late 1800s and early to mid-1900s mandating racial segregation in public facilities. They reflected a social construction of race that labeled Black people as biologically inferior to white people and inherently lazy, promiscuous, irrational, and resilient to pain.[7] (Also see Appendix 2: Racist Narratives of Black Women.)

Forced reproduction and labor were standard practices of white enslavers to exploit, control, and punish enslaved Black women.[8] White enslavers wanted to maximize their economic returns by controlling Black women’s reproduction.[9] Under enslavement, Black women were punished when they did not bear children. State laws further incentivized the sexual abuse of Black women: the rape of an enslaved woman was not recognized as a crime and all children born to enslaved women were legal property of the enslaver.[10]

Even pregnancy did not always protect women. In one especially horrific example, some enslavers dug holes in the ground and forced pregnant women to put their belly in the hole to “protect” the child as they were whipped.[11] The expectation that Black women have children did not reduce the amount of work demanded of them; pregnant women often worked to the point of miscarriage and new mothers had to work, sacrificing the health — and often the lives — of their babies.[12]

Enslaved women, men, and children did back-breaking work in fields, homes, and even factories. In the fields, women could work 12 to 16 hours a day. Black women not working in the fields worked as laundresses, maids, cooks, nurses and midwives, and caregivers for both Black and white children.[13] They were violently punished if they did not work or produce according to the enslaver’s expectations. Enslavement narrowly defined the types of work acceptable for Black people as those that benefited white people, one historian argues.[14] For 250 years the unpaid and coerced labor of Black men, women, and children drove large parts of the American economy.[15]

After emancipation and the brief hope of a transformed system under Reconstruction, the “freedom” that many Black people experienced differed little from enslavement. In 17 Southern states,[16] legislatures cemented a white supremacist socioeconomic order through Jim Crow laws that lasted nearly a century, while sanctioning anti-Black violence by white individuals and mobs. (De facto segregation and anti-Black violence also existed in Northern states.[17]) White policymakers and employers continued to control when and where many Black people worked. White landowners’ system of sharecropping trapped Black people in debt, which their meager earnings could rarely pay off. Vagrancy laws and other policies criminalized Black people for sometimes trivial behaviors simply because local white officials deemed them not to be working.

These laws led to different forms of involuntary servitude, such as convict leasing, chain gangs (groups of imprisoned people forced to work on roads or other public infrastructure), and debt peonage (in which employers forced workers to pay off debt with work).[18] State officials also found other ways to make Black people work. For example, in 1918, at least two Southern localities attempted to legally coerce Black women to work in response to fears that they were refusing to work because of the payments some were receiving due to their husbands’ service in World War I.[19] Jim Crow laws controlled other behaviors by denying Black people’s right to vote and telling them where they could eat, walk, sit, and spend their money, among other things.

Anti-Black violence was another means of controlling Black women. For example, many Black women still did not have full control over their sexual and reproductive decisions. Black women and girls were systematically raped by white men in a parallel to the reign of terror in which thousands of Black people were lynched.[20] Cole Blease, governor of South Carolina from 1911 to 1915, pardoned both white and Black men convicted of raping Black women, stating, “I . . . have very serious doubt as to whether the crime of rape can be committed upon a negro.”[21]

Centuries of Black women’s forced reproduction and labor was foundational to the white-dominated order as the country moved into the 20th century. Given the history, it is not surprising that later policies would continue to exclude Black women from public assistance programs in the belief they would not work otherwise and continue to punish their sexual or reproductive decisions.

The idea that only families meeting specific criteria deserve government support dates back to the beginnings of cash assistance. In the early 1900s, white middle-class women reformers known as maternalists sought to address increasing destitution among widowed mothers and their children that accompanied industrialization,[22] but only for those they believed were “deserving.” Their proposal for mothers’ pensions — designed to enable children to be cared for in their homes if their families lost a male breadwinner due to death, abandonment, or poor health — found support in a 1909 White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children, which concluded that:

Children of parents of worthy character, suffering from temporary misfortune, and children of reasonably efficient and deserving mothers who are without the support of the normal breadwinner, should as a rule, be kept with their parents, such aid being given as may be necessary to maintain suitable homes for the rearing of children… Except in unusual circumstances, the home should not be broken up for reasons of poverty, but only for considerations of inefficiency or immorality.[23]

Mothers’ pensions, funded and operated by states or local governments, were first established in the 1910s, starting with Illinois’ program in 1911.[24] Dozens of states and localities followed Illinois’ lead by the mid-1920s.

Mothers’ pension programs reflected traditional ideas about marriage and gender roles. When caseworkers determined that a family’s composition or a mother’s conduct did not align with these expectations, they were deemed unworthy of aid.[25] White children of widowed mothers, who made up the vast majority of mothers’ pension recipients, were seen as deserving because they lost their breadwinning father through no fault of the mother.[26] Children of unwed mothers — of any race — were usually excluded.[27] Fewer than 0.1 percent of mothers’ pension children had unwed mothers, a 1933 study found. [28]

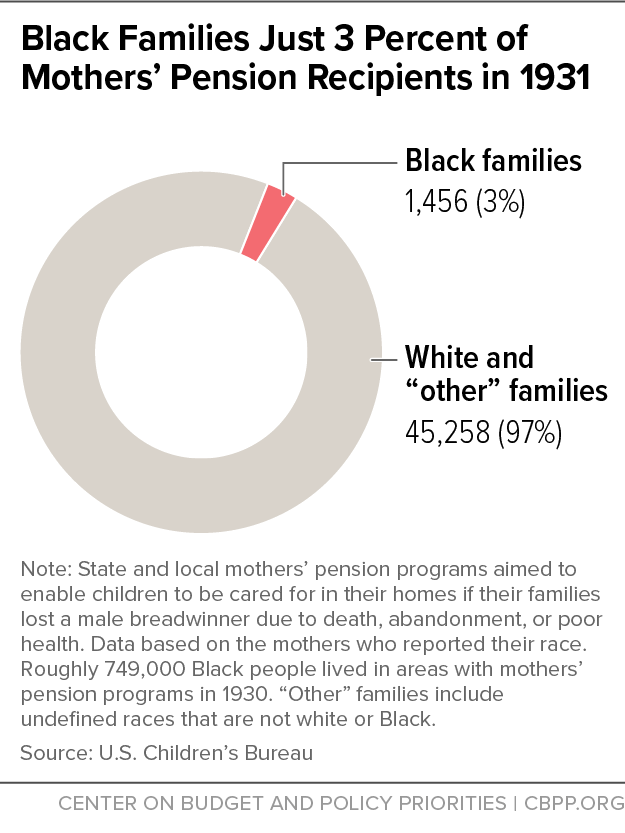

Children of Black mothers were also largely excluded, regardless of whether the mother was widowed, abandoned, or unwed and regardless of economic need.[29] Only 3 percent of families whose race was reported in the 1931 study had a Black mother.[30] (See Figure 2.) Black families were more likely to access programs in Northern and Midwestern states; together, Ohio and Pennsylvania had about half of all identified Black families receiving mothers’ pension aid. (See Appendix Table 1.) Yet while thousands of Black people were moving north and to urban centers during this era as the Great Migration began, most Black people still lived and worked in the rural South. Mothers’ pension programs were very small overall in the Deep South and only served 39 Black families in 1931, compared to 2,957 white families.[31] (See Appendix Table 2.) Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina were three of the four states that did not even have programs established by 1931.[32]

For families with access to mothers’ pensions, benefits were generally low. Limited funding for local programs was one reason, but some local administrators also held concerns about giving mothers too much cash and questions about how they would use it.[33] For example, one administrator feared married women would leave their husbands if they thought they could live independently.[34] In 1931, most states with programs had average monthly grants at or below $30, or about $452 in 2021 dollars. Sixteen states, eight of them in the South, had average monthly benefits of less than $20, or about $302 today. [35]

States and localities controlled eligibility and benefits for mothers’ pension programs, and states maintained much of that power in later cash assistance programs. As discussed below, those later programs continued to limit access to certain families and set low benefits.

New Deal and Aid to Dependent Children: Excluding Black Women From Social Insurance

The creation of Aid to Dependent Children (ADC, renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC] in 1962) as part of the 1935 Social Security Act marked the beginning of the federal government’s ongoing role in providing cash assistance to children in poverty. But ADC and other New Deal relief and work programs excluded many Black and brown people.[36]

For example, policymakers originally designed unemployment insurance and retirement insurance primarily to support white male breadwinners.[37] Even though unemployment was extremely high among Black workers — up to 80 percent in some places as of 1932[38] — the new unemployment insurance programs explicitly excluded agricultural and domestic workers, the sectors where most Black women worked. Social Security’s retirement insurance excluded agricultural and domestic workers as well. As a result, 90 percent of Black women laborers were initially ineligible for these social insurance programs[39] and two-thirds of Black women workers were still ineligible a full decade later.[40]

Southern legislators demanded unfettered state control over ADC, which provided funding to states to assist children who were “deprived of parental support or care by reason of death, continued absence from the home, or physical incapacity of a parent” and who lived with a parent or relative.[41] The program was intended to be small; many of the policymakers designing it (almost all of whom were male) assumed that not many single mothers needed this support, and not many were “deserving” of assistance.[42] The Roosevelt Administration wanted to set federal standards for benefits, but Southern members of Congress insisted that state and local officials control ADC eligibility and benefit levels. Their goal, according to a number of historians, was to preserve an economic system that relied on the low-wage labor of Black workers in the South and Latinx workers in the Southwest.[43]

As a result, the Great Depression pushed more Black families — who were already struggling under exploitative work conditions, discrimination, and segregation — deeper into poverty. White workers replaced Black workers in many unskilled jobs usually reserved for Black workers. Black sharecroppers, already paid less than their white counterparts, saw their wages drop or lost their jobs altogether. Black women domestics could sometimes still find work but often at a fraction of the low wages they received in better times.[44] Yet despite the extremely high poverty levels among Black families, they made up only 14 to 17 percent of the ADC caseload between 1937 and 1940 and an even smaller share in Southern states, where more than three-fourths of the Black population lived in 1940.[45] Mississippi did not even start an ADC program until 1941.[46] Many Southern states continued to deny Black families access to ADC because, in the words of one historian, they did not want to “interfere with local labor conditions.”[47] As one field supervisor put it, Black families “have always gotten along” and if made eligible for assistance, “all they’ll do is have more children.”[48]

World War II and Postwar: Punitive Policies to Control Mothers

The early 1940s marked a shift in the composition of the ADC caseload. White widows began leaving ADC after Social Security expanded eligibility to include survivors of qualified workers in 1939.[49] This increased the share of ADC recipients who were Black, divorced, separated, or unwed mothers. After wartime jobs ended and other jobs moved to the suburbs, many women sought out public support;[50] the program grew from 372,000 families in 1940 to 652,000 in 1950, a 75 percent increase. With more Black families living outside the South and thus better able to access the program, their share of recipients grew from 17 percent to 31 percent over this period.[51] The postwar years also saw growing rates of divorce and of births to unmarried mothers. The ADC caseload and share of Black families steadily grew throughout the 1950s.[52]

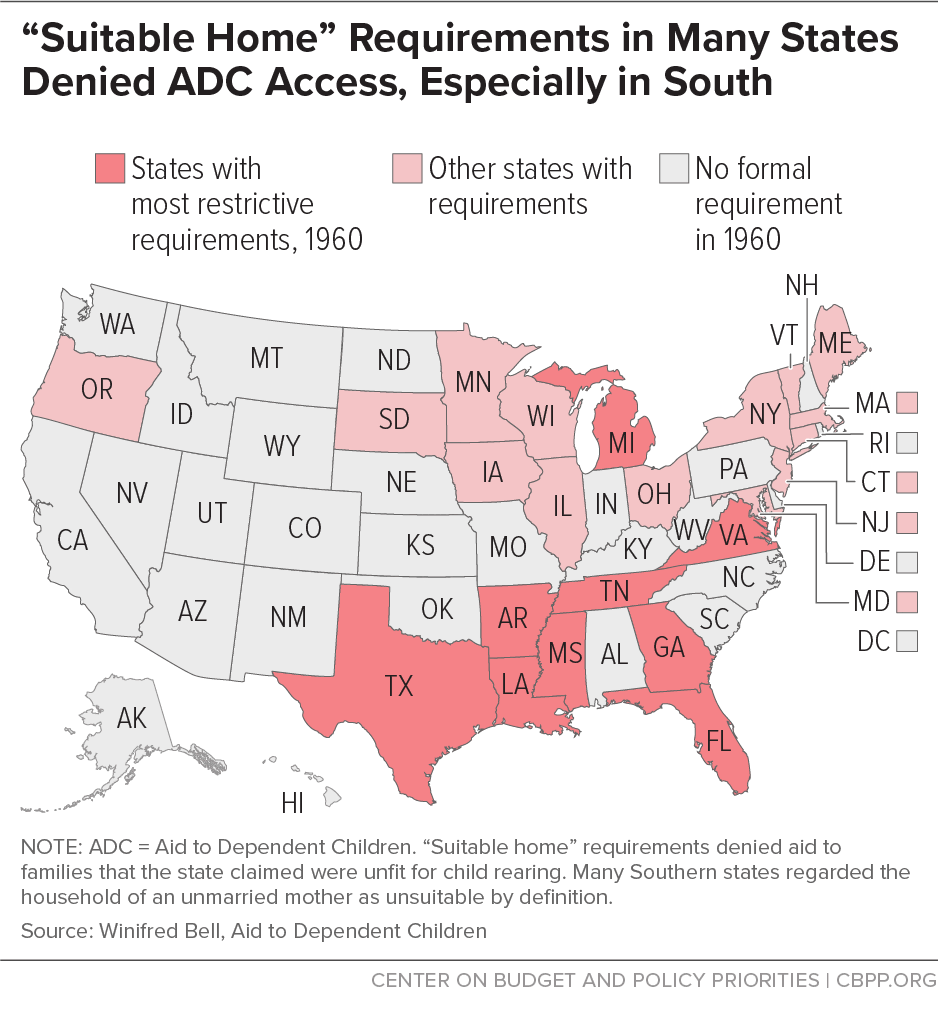

Policymakers in a number of states criticized the types of families receiving ADC and the program’s rising costs and implemented punitive policies that disproportionally harmed Black families. So-called “suitable home” and “man-in-the-house” rules kicked off or denied initial access to mothers who engaged in activity deemed morally or sexually deviant.[53] The goal of the new rules, as one Georgia policymaker put it, was to “clean up” the rolls.[54]

“Suitable home” laws, meant to protect children from maltreatment and neglect and support their health development, allowed states to deny aid based on health or moral determinations of a home’s fitness for child rearing. Between the late 1940s and early 1960s, 23 states passed or instituted “suitable home” requirements. In many Southern states, the “suitable home” policy regarded the household of an unmarried mother as unsuitable by definition.[55] Often these policies specifically targeted Black mothers and their children. In perhaps the most extreme example, Louisiana’s 1960 “suitable home” laws cut off more than 6,000 families from the program within three months; 95 percent of the children in those families were Black.[56] (See Figure 3.)

“Man in the house” or “substitute father” laws cut aid to families if the mother cohabitated with a man who was not the children’s father. They were based on the assumption that the man could or should provide for the children even if he had no legal obligation to the child, was a casual romantic partner, had little or no income, or was simply a boarder.[57]

Policymakers disproportionately implemented these policies in jurisdictions with high Black populations. Several states and localities created special units in their ADC agencies to conduct home searches, sometimes called “midnight raids,” in search of a cohabitating man in the home. These included Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., Cuyahoga County, Ohio (which encompasses Cleveland), Wayne County, Michigan (which encompasses Detroit), and the states of Illinois and Pennsylvania.[58] ADC/AFDC agencies often cut off families based on tenuous evidence that a cohabiting man was a romantic partner or had the resources to provide for the children.[59]

In addition, white lawmakers in several states proposed eugenic legislation in the late 1950s and the 1960s calling for sterilization of unmarried ADC/AFDC mothers. Often they cited Black mothers in particular: “The negro woman, because of child welfare assistance, [is] making it a business, in some cases of giving birth to illegitimate children,” Mississippi State Representative David H. Glass argued.[60] In 1958, he introduced a bill to allow a court to order sterilization for women who give birth to a “second or subsequent illegitimate child,” implicitly targeting mothers receiving ADC/AFDC benefits. Illinois, Iowa, Ohio, Tennessee, and Virginia considered similar proposals for compulsory sterilization of mothers receiving ADC/AFDC benefits who had children while unmarried. No state enacted a sterilization proposal for ADC/AFDC mothers, but many states operated sterilization programs targeting people of color, people in poverty, people with mental illness, and others, some of which continued into the 1970s.[61]

Southern states also used ADC to exert economic control over Black families. So-called “farm policies” in a number of states lowered or cut off ADC benefits during planting and harvest seasons to coerce Black parents to work in agriculture even if no paying jobs were available.[62] For instance, Louisiana’s 1943 policy denied assistance during the cotton-picking season to both newly applying families and those already receiving assistance.[63] Beyond the South, agricultural communities in Illinois and New Jersey also adopted farm policies that targeted Black families.[64]

Some policymakers in the North also denounced Black migrants moving to their cities, who they claimed were only seeking more generous ADC benefits. Newburgh, New York, was ground zero for this attack. Blaming “Southern outsiders” seeking cash assistance for the decline in the city’s standard of living, the city council adopted a “thirteen-point welfare code” that, among other things, required all ADC applicants who were new to Newburgh to provide evidence that they had a concrete offer of employment. The ensuing controversy, which the media dubbed the “Battle of Newburgh,” gained national attention, and a court order permanently blocked the new rules.[65]

1960s and 1970s: Federalizing Eligibility But Adding Work Requirements

The 1960s and 1970s saw enactment of significant civil rights legislation and expansions in economic support programs as part of the War on Poverty. These gains reflected growing recognition that all Americans weren’t sharing fully in the postwar prosperity. While white families garnered most of the initial attention in poverty debates in the early 1960s, the political work of Black activists, urban uprisings, and the rise in the number of Black families receiving AFDC focused more of the nation’s attention on poverty among Black people.

Historically, Black women have always had higher work rates than white women[66] but were often segregated into jobs with low pay, such as domestic service. Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, opened up new economic opportunities for Black and other women. More Black women moved into higher-paying, professional jobs in the 1970s, though many continued to do the same work they had always done. The entry of more married white mothers into the labor market in the 1970s contributed to the rise of jobs in commercial child care centers, many of which Black women filled.[67] Those jobs were unstable and low paid. And, even before a recession hit in 1973, the unemployment rate for Black women exceeded the rate for the country overall.[68] Black and other single mothers who could not find work or get unemployment insurance increasingly applied for AFDC.

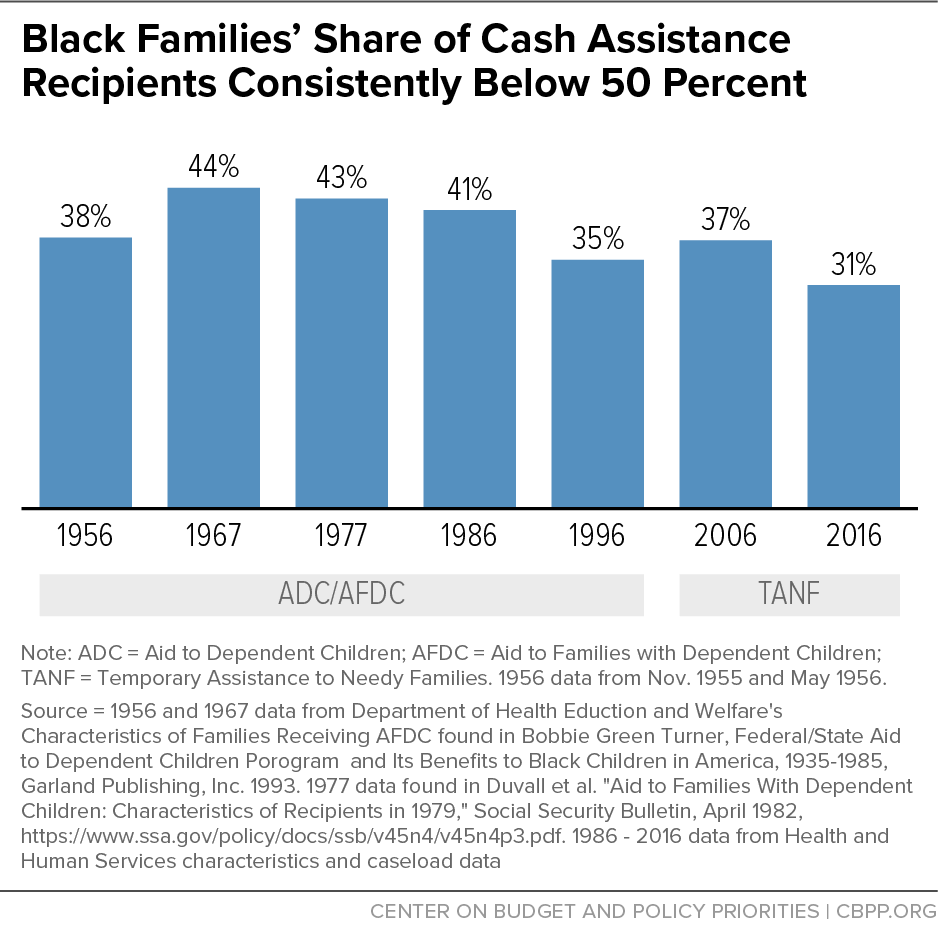

With expanded eligibility and continued need among many single mothers in poverty, the AFDC caseload grew from roughly 1.3 million families in 1967 to about 3.6 million in 1977.[69] While the number of AFDC Black families grew in this decade, it rose in proportion to the caseload; Black families’ share of the program dropped slightly, from 44 percent 1967 to 43 percent in 1977.[70] (See Figure 4.) Nevertheless, the perception of skyrocketing growth of Black families receiving AFDC and the program’s increased costs, along with the social unrest in Black communities, alarmed some national policymakers and affected media coverage of poverty-related issues. One of the main legislative responses was greater focus on work for AFDC recipients.

In the early 1960s, federal administrators started taking a harder line to limit state flexibility over AFDC eligibility. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) had long been concerned about states denying access to Black families and families with unmarried mothers, but it had done little to end discriminatory state practices and had limited tools to encourage states to change their policies.[71] Not until the 1960s did HEW take a firm stance. In response to Louisiana’s denial of AFDC support to thousands of Black children, HEW issued an administrative rule in 1960 (known as the Flemming rule after HEW head Arthur Flemming) that states could not ignore the needs of the child if the home was determined to be “unsuitable;” state AFDC agencies had to help make the home suitable or move the child to more suitable living conditions, or risk loss of federal funding.[72] This was HEW’s firmest rule to date, but it did not end all policies restricting access for Black and unwed mothers such as “farm policies” and “man in the house” rules.

Also in the 1960s, the welfare rights movement made substantial progress in expanding AFDC eligibility. A key leader of the welfare rights movement was the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO); it was created in 1966 when organizers brought together Black, brown, and white mothers receiving cash assistance who had been organizing locally for dignity and more benefits since the late 1950s.[73] To ensure that Black families could access assistance, the NWRO sought to end discriminatory practices by pressuring state and local AFDC agencies to increase benefits and stop denials.

The NRWO not only agitated on the ground, but also supported the efforts of lawyers in the movement pushing for greater enforcement of federal eligibility standards in the courts.[74] They won key Supreme Court cases that ended some of the most harmful state eligibility rules discriminating against Black families and precluded states from restricting eligibility. The Court’s 1968 ruling in King v. Smith, for example, struck down Alabama’s “substitute father” policy and eliminated other “man in the house” rules; it also barred states from instituting additional eligibility rules, thereby shifting the power to determine eligibility restrictions from the states to the federal government.[75] And in Goldberg v. Kelly (1970), the Court ruled that AFDC recipients had a right to a hearing before their benefits were terminated, among other due process measures.[76] The NWRO then pushed for enforcement of these protections when some states resisted changing their policies.[77]

These rulings effectively ended many states’ arbitrary eligibility policies and processes and barred states from adding work or behavioral requirements or eligibility policies that were more restrictive than federal law. Federalization of AFDC eligibility had its limits, however; states retained control over benefit levels, which varied widely across states and tended to be lower in states with higher Black populations.[78] Also, almost all states allowed benefits to decline in inflation-adjusted terms between the 1970s and 1990s.[79]

Though Black families never made up a majority of the AFDC caseload, the news media increasingly associated the program with Black families starting in the mid-1960s. Incidents in Louisiana and Newburgh, New York, involving efforts to prevent Black families from accessing the program gained national attention. Also, after the urban uprisings of the mid-1960s, news stories about waste, fraud, or abuse in public assistance programs (especially in AFDC) increasingly featured images of Black people, while stories about recessions and increased need were likelier to feature images of white people.[80]

In 1965, a major report from Assistant Labor Secretary Daniel Patrick Moynihan that elevated racist and sexist ideas about Black motherhood and families represented the shifting of the public discourse about poverty. “The Negro Family: The Case For National Action,” more commonly known as the “Moynihan report,” stated, “[i]n essence, the Negro community has been forced into a matriarchal structure which, because it is so out of line with the rest of the American society, seriously retards the progress of the group as a whole.”[81] Though the report acknowledged that subjugation and discrimination had limited Black men’s economic advancement, it blamed Black single mothers for continued poverty and crime in Black communities and charged that women-led families perpetuated a culture of “pathologies.”[82]

The Moynihan report, which attributed the growth of AFDC caseloads to the deficient values of the Black community, helped change the mainstream public debate over the causes of poverty from economic to cultural explanations, and conservative scholars like Charles Murray and Lawrence Mead later used the “culture of poverty” as a rationale for their proposals to narrow or end AFDC. Though the report focused on Black fathers, it likely furthered calls from both conservative and liberal policymakers for changes to AFDC, including work requirements for Black and other mothers on the program.[83]

With AFDC becoming closely associated with stereotypes of Black mothers, efforts to expand cash assistance met fierce criticism. Opponents of President Nixon’s proposed Family Assistance Program (FAP), which would have replaced AFDC with a minimum basic income for married or unmarried households that would have been higher than AFDC benefits in some states and included work requirements and work incentives, invoked racist stereotypes about Black women’s work ethic echoing back to the justifications for enslavement.[84] For example, Senator Russell Long of Louisiana, fearing that some poor people would opt for FAP benefits over low-wage jobs, lamented, “I can’t get anybody to iron my shirts.”[85]

Media outlets and some policymakers reinforced these perceptions, claiming there was a “welfare crisis” of growing costs supporting “undeserving” families. For example, a 1971 U.S. News & World Report article entitled “Welfare Out of Control” charged that AFDC “encourages illegitimacy among those who are least equipped to bring up children”[86] and implied that families in the “slum” cheated to get on welfare.[87] In a 1976 campaign rally, presidential candidate Ronald Reagan defended his plan to cut AFDC and other social programs (which he had done as governor of California[88]) by citing the example of a woman named Linda Taylor,[89] who used numerous false identities to collect benefits from various public sources and would later be known as the “welfare queen.”

Later depictions of this “welfare queen” stereotype embodied many of the harmful narratives about Black women in a single phrase: “welfare queens” were lazy cheats who irresponsibly had a lot of children and relied on and abused public aid. (See Appendix 2.) These stereotypes weakened public support for AFDC. By 1976, 89 percent of Americans believed that “the criteria for getting on welfare are not tight enough,” while 85 percent thought that “too many people on welfare cheat by getting money they are not entitled to.”[90]

In reality, families were not living comfortably on cash aid. Even with cash assistance and food assistance, families in poverty struggled to afford the basics. Between the early 1970s and early 1980s, AFDC benefits started shrinking in inflation-adjusted terms even as housing costs rose.[91] By 1980, the maximum AFDC benefit didn’t lift a family of three out of poverty in any state.[92]

Work Program Expansion and Tying Eligibility to Work

The 1960s and 1970s saw the first steps toward the policies we see today in TANF that take away assistance from families where an adult doesn’t meet a work requirement. The entry of more mothers, especially white mothers, into the workforce shifted public expectations about single mothers and work outside the home. Additionally, growing media attention to a “welfare crisis” and claims that AFDC incentivized women not to marry or work pressured federal policymakers to adopt a new approach to single mothers living in poverty.[93] Many began moving away from the idea that AFDC mothers’ primary responsibility should be caring for their children in the home, rather than working.

Liberal Democrats in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations tried to find a balance between encouraging work and protecting single mothers’ right to care for their children instead of being required to work for pay outside the home.[94] In contrast, Southern Democrats, emboldened by AFDC’s negative media attention, favored a broader work focus for AFDC mothers. In 1967, Democratic Representative Wilbur Mills from Arkansas[95] pushed through Congress his Work Incentive Program or WIN, which required states to establish work programs for AFDC recipients and allowed recipients to earn income without losing their benefits on a dollar-for-dollar basis.[96] In 1971, Senator Herman Talmadge, former Georgia governor and long-time segregationist,[97] successfully amended the Social Security Act to expand AFDC’s work requirement: mothers with no children under age 6 had to register for work programs and accept any available job or else face a benefit reduction.[98]

The NWRO pushed back forcefully against WIN and work requirements,[99] charging that the training and job placement provided under WIN were useless because they often placed women into work that Black women and other women in poverty had always done, such as cooking and cleaning.[100] Many NWRO leaders compared WIN to enslavement and said mothers did not need to be coerced to work.[101] Because AFDC benefits were so meager, mothers on AFDC worked when they could, but formal child care was still largely unavailable.[102] Even in good economic times, Black women had higher unemployment rates than the country as a whole.[103] A 1977 study found that WIN did not improve AFDC families’ circumstances and attributed its failure to labor market barriers, not lack of work ethic.[104]

To improve economic security for single mothers and their children, NWRO Executive Director Johnnie Tillmon called for a living wage and passage of the NWRO’s Guaranteed Adequate Income[105] proposal to assist families at times when parents could not work or their earnings were not enough.[106]

1980s and 1990s: “Personal Responsibility” and Return of State Control

By the start of the 1980s, both Republican and Democratic policymakers believed that AFDC encouraged dependency and undermined family values and recipients’ work ethic.[107] A powerful conservative coalition emerged to push for lower taxes and smaller government; its members strongly supported cutting anti-poverty programs after their growth in the 1960s and 1970s. The media continued to racialize AFDC as a backdrop to debates surrounding “welfare reform.” In the 1990s, sensationalized cases of child abuse in Black and Latinx families receiving AFDC were covered in a way that aligned with the pre-established racist narratives that the program supported “unfit” mothers.[108]

While public figures largely abandoned overtly racist language in public, many instead used dog whistles such as “illegitimate births,” “inner city,” and “crime” to invoke negative images of Black families and communities and undermine support for cash assistance.[109] And they crafted seemingly race-neutral ideas like “work requirements” and “personal responsibility” to describe their solutions. The news media and some politicians had already linked AFDC to stereotypes about Black women, as noted above; some also blamed urban poverty and crime on Black unwed mothers. Therefore, the public understood which group was the target of the new policy proposals.[110]

The racist rhetoric and narratives were not limited to the Republican Party. President Clinton would eventually justify his Administration’s policies, which included acceptance of arbitrary time limits on cash assistance and work requirements that would hurt many people, by claiming that “welfare reform” would end the racial politics then driving anti-poverty policy.[111] Yet in the photo of him signing the legislation that created TANF, he was flanked by two Black mothers and former AFDC recipients, Lillie Harden and Penelope Howard.[112]

Conservative intellectuals and think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation and American Enterprise Institute pushed for dramatic cuts in anti-poverty programs.[113] For example, scholars like Charles Murray and Lawrence Mead, who had both made racist arguments about the “inferiority” of Black and Latinx people,[114] faulted AFDC and other programs for reinforcing a “culture of poverty,” especially among communities of color.[115] Murray blamed anti-poverty programs for the decline of the traditional nuclear family and the rise of births to unmarried mothers, particularly Black mothers. He recommended eliminating AFDC for non-disabled adults and insisted they work, regardless of job quality or compensation — echoing Southern policymakers’ efforts to preserve the Black low-wage labor force in the early 20th century. Mead did not go as far as calling for ending the program, but instead argued for more paternalism and control of AFDC families, and that parents should be required to meet “social obligations” like work to receive assistance.[116]

Yet contemporary research did not support the thesis that programs like AFDC led to increased rates of Black children born outside marriage. A 1984 report by social policy researchers David Ellwood and Mary Jo Bane found no connection between state benefit levels and the rates of children born outside marriage.[117] Other studies supported this finding.[118] And, as noted, the real value of benefits started declining in the 1970s even as rates of children born outside of marriage rose.[119] “Welfare simply does not appear to be the underlying cause of the dramatic changes in family structure of the past few decades,” Elwood and Bane concluded.[120]

The reality was that many Black women were struggling to work and/or care for children amid many larger forces that AFDC’s critics ignored. Over the previous few decades, adults had delayed marriage longer and longer.[121] Birth rates among teenage girls had declined since mid-century,[122] perhaps due to the decline in their marriage rates, but birth rates grew for Black and white teenage girls in the 1980s and 1990s.[123] At the same time, the economy was changing in ways that made it harder for families to maintain economic stability. Deindustrialization in urban areas eliminated stable, well-paying jobs for many Black men, making it difficult to provide for their families.[124] Black women were still overrepresented in lower-paying service jobs such as housekeeping, child care, and food service, which tended to be unstable.[125] Also, the real value of wages started declining in the 1970s, making it even harder for workers with low earnings to make ends meet.[126] These factors increased income instability among people with the lowest incomes.[127]

During the 1980s, people of color with low incomes were likelier to face increased income volatility and to be between jobs.[128] Black women were frequently among the last to recover from recessions, including those of the early 1980s and early 1990s.[129] Also, new crime laws and mass incarceration targeted Black people, further destabilizing Black families and communities throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Finally, there remained deep inequities in education and housing, resulting in Black children often attending under-resourced schools and continued disparities in the share of Black and white people who attained a four-year college degree at a time when returns to higher education were growing. The cuts to AFDC and eventual creation of TANF disregarded these realities.

Several bills enacted during the 1980s included fiscally driven AFDC cuts and modest changes to work programs and related services. The two most significant bills were both influenced by racist attitudes toward cash assistance recipients.

President Reagan gained support for cutting public aid programs by repeating the “welfare queen” trope and raising the specter of widespread waste, fraud, and abuse.[130] “[I]n addition to collecting welfare under 123 different names, she also had 55 Social Security cards,” he said in 1981, referring to Linda Taylor, who had been convicted of welfare fraud. (See above.) “[T]here’s much more of [this type of fraud] than anyone realizes,” he claimed.[131] The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 cut AFDC spending, but by limiting eligibility rather than reducing supposed fraud. For example, some of its cuts limited work incentives, ironically cutting off many working mothers in the name of “targeting” help to those who needed it most. The changes caused about 1 in 6 families to lose some or all of their benefits.[132] The law also expanded states’ flexibility to design their own work programs and to require recipients to participate in unpaid community service or work programs in exchange for their AFDC benefit.

In Reagan’s second inaugural address in 1985, he claimed he wanted to help families in poverty “escape the spider’s web of dependency.”[133] His second attempt to change AFDC furthered the focus on work programs. The 1988 Family Support Act (FSA) established the Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Training program (JOBS) to replace WIN and allowed states to require mothers with children over age 3 (the previous rule was over age 6) to participate in work, education, or training. Mothers not meeting these requirements could have their grant reduced.[134] There were some more positive advances: the FSA guaranteed child care (with federal matching funding) for parents receiving AFDC who were working or in education or training programs, as well as transitional child care for up to one year after a family left AFDC for employment — a recognition that parents need child care in order to work.[135] However, efforts to create federal requirements on the adequacy of benefit levels were rejected.[136] The FSA’s approach of marrying more restrictive work requirements with added resources was overshadowed by calls for more radical changes within just a few years.

The 1990s debate surrounding AFDC policy was, like previous such debates, deeply racialized. Proponents of dramatic changes often compared them to ending slavery. Milwaukee Mayor John Norquist stated in 1993, “In 1863, Lincoln freed the slaves of the Confederacy — and in 1865, all the slaves were freed. . . . [W]e can liberate America’s poor from an oppressive welfare system and help them get what they really want and the rest of us believe in: work.”[137] Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson invoked values he associated with whiteness, stating, “People in Wisconsin expect people to work — maybe it’s the old Germanic heritage, the old European heritage,”[138] while New Jersey State Representative Wayne Bryant wrote that the values of his Black Camden community need to align with the rest of the country.[139] House Minority Whip Newt Gingrich promoted his “Contract with America,” which contained radical AFDC changes as well as other proposals the Republican Party adopted for the 1994 elections, by stoking fears of the inner city: “[W]atch any major city local television news. . . . The child abuse, the rape, the murders, the cocaine dealing, the problems of American life are unbelievable. . . . [I]t is impossible to maintain American civilization with 12-year-olds having babies, 15-year-olds killing each other, 17-year-olds dying of AIDS, and 18-year-olds getting diplomas they cannot read.”[140]

Federal control over AFDC eligibility began eroding in the late 1980s and early 1990s as states sought to impose new requirements and restrictions such as time limits, increased work requirements, and more severe penalties. Particularly in the early and mid-1990s, states sought waivers of federal law (available under section 1115 of the Social Security Act) to change benefit eligibility and requirements. Keeping with President Clinton’s campaign promise to “end welfare as we know it,” his Administration approved waivers in 43 states.[141] Waivers varied by state but were often more punitive, and their work provisions more extensive, than federal policy would otherwise allow. Many programs took all cash assistance away from families that didn’t comply with work requirements and set time limits on assistance. These harsh proposals were often coupled with rules (known as expanded earnings disregards) that phased down benefits more slowly if people’s earnings rose as a way to encourage employment.

This theme of expanding the rewards to work while cutting basic assistance to people who are out of work can be seen in policy changes related to cash aid and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a refundable credit created in 1975 that supplements the earnings of families with low earnings. Policymakers expanded the EITC in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with President Clinton touting the expansion as a major accomplishment in his 1993 budget even as his Administration was approving waivers that made it harder for families in which an adult wasn’t working to get basic cash assistance.[142] Together, the rise of EITC expansions and policies that take cash aid away from families when an adult doesn’t meet a work requirements show a major shift toward conditioning assistance on work.

In addition to calling for work requirements, many public officials and conservative intellectuals wanted to address the growth of births to single mothers, particularly for Black teenagers but also an increasing number of white teenagers, and AFDC’s supposed role in that growth.[143] Many state waiver plans included family caps, which denied families the standard incremental increase in their benefits to account for the added costs of meeting the needs of a child born to a family receiving AFDC. One HHS official spoke in favor of states’ family cap policies by saying the government should not reward “irresponsible” behavior.[144] New Jersey State Representative Wayne Bryant wrote in a Washington Post op-ed, “If parents are so irresponsible that they are unwilling to come to work or go to school, what makes you think they’re taking the added welfare dollars and spending them responsibly on their kids?”[145] He believed his state’s family cap policy and other AFDC changes would transform the lifestyles of his predominately Black hometown of Camden.[146]

Some states considered other ways to limit AFDC mothers’ reproduction. In the early 1990s, legislators in several states proposed bills to pay teenage mothers on AFDC who agreed to have Norplant, a long-acting reversible contraceptive device, implanted in their arms. Other state proposals (none of which passed) would require women to accept Norplant as a condition of receiving AFDC. Outside of official AFDC policy, health professionals often targeted Norplant to Black teenage mothers receiving AFDC and Medicaid; a 1990 editorial in the Philadelphia Inquirer suggested it could be used to control the Black birth rate and reduce poverty. [147]

In addition to granting state waivers, President Clinton also pursued broader “welfare reform” to deliver on his campaign slogan to “end welfare as we know it,” unveiling a proposal in 1994 that included time limits (followed by work, including an offer to be placed in an unpaid job if needed).[148] Just months later, however, Republicans and Speaker Newt Gingrich took control of the House and became the drivers of the policy and process. The “Contract with America” called for dismantling AFDC, framing the issue as “personal responsibility” and that if people living in poverty had jobs and got married or paid child support, their families would no longer need cash assistance. (It didn’t mention that jobs were not always available or that many paid very low wages.) One Republican bill introduced in 1995 included a state option to deny cash aid to young unwed mothers and a state option to establish orphanages.[149] Proposals such as these were not too distant from the racist “suitable home” laws and “farm policies” that predominated in the South in mid-century.

Congressional efforts to pass legislation lasted over 18 months, with President Clinton vetoing two bills before signing the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWORA) in August 1996.[150] PRWORA replaced AFDC with the TANF block grant, wiping out federal eligibility rules and stating that cash assistance was not an entitlement to any individual or family.

TANF’s four main purposes reflected the rhetoric of the “reform” era of the 1990s.

- Provide assistance to needy families so that children can be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives.

- End the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage.

- Prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies.

- Encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

The TANF block grant is fixed in dollar terms but gives states nearly full control over how they can spend it, within the broad parameters of those four purposes. TANF largely allows states to set their own eligibility policies and work and behavioral requirements and thus to reverse the gains in the 1960s and 1970s from federalizing eligibility rules. States face some restrictions and penalties, but these generally limit their ability to be generous, not to restrict access; for example, they cannot use federal funds to provide cash assistance for more than 60 months or to serve most lawfully present immigrants for five years after their arrival. TANF includes increased work requirements on recipients as well as work participation rates that states must achieve.

Both the fixed funding and the state work participation rate requirements were designed to give states strong incentives to reduce caseloads. States responded by making it harder for families to successfully apply for TANF and easier for families to lose all assistance, including through the use of sanction policies that take all assistance away from an entire family if a parent doesn’t meet a work requirement. TANF’s creation was indeed the end of “welfare as we know it.”

TANF does not work well for most families experiencing poverty and does the least for Black families. Nationally, the number of families receiving AFDC/TANF fell by 76 percent between 1996 and 2019, from 4.4 million to 1.1 million.[151] In 1996, 68 families with children received benefits for every 100 families in poverty; by 2019, that figure had dropped to 23, nearly the lowest TANF-to-poverty ratio in the program’s history. TANF cash assistance has all but disappeared in some places due to state actions. Fourteen states have a TANF-to-poverty ratio of 10 or fewer, and these states have higher shares of the nation’s Black children than of Latinx or white children.[152] Below are some of the ways states have made cash assistance programs for families with children worse under TANF.

As noted, in 1935 Southern lawmakers demanded state control over ADC benefits so they could maintain a Black labor pool with few alternatives to low-wage work. States used this control to keep benefits weak in later decades. States with large Black populations had lower average AFDC benefits than states with smaller Black populations and Southern states consistently had among the lowest benefits, research found.[153] Also, the far broader flexibility that states gained under the TANF block grant has allowed them to divert savings in their cash aid programs to fund other state priorities. As caseloads declined under TANF, states generally didn’t invest the savings to provide more adequate cash assistance. In fact, benefits under TANF have lost value in nearly all states and in some states are below 1996 levels even before adjusting for inflation.

Since 1996, 33 states’ benefits have lost at least 20 percent of their purchasing power. In 2020, benefits in nearly every state were below half of the federal poverty line, or below $905 a month for a family of three. Eighteen states, 14 of which are in the South, had benefit levels at or below 20 percent of the poverty line — that is, $362 a month or less for a family of three. Fifty-five percent of the nation’s Black children live in the 18 states with the lowest benefits, compared to 41 percent of Latinx children and 40 percent of white children.[154] Mississippi is a prime example of TANF’s failure to meet the needs of Black children: the state has a child poverty rate of 28 percent and a Black child poverty rate of 43 percent[155] but its maximum TANF benefit was, until April 2021, the lowest in the country.[156]

Despite TANF proponents’ pro-work rhetoric, neither the federal statute nor state implementation efforts demonstrated a commitment to giving participants a meaningful, effective connection to permanent employment with adequate wages. Cash assistance programs that focus up front on employment and take assistance away from parents who aren’t able to meet a work requirement do little if anything to improve employment outcomes over the long term, research shows. They also leave many families without needed assistance to make ends meet. A re-review of early TANF studies found initial positive employment impacts from programs that emphasized immediate employment — impacts used to justify a focus on immediate employment over education and training — but that these benefits faded over time.[157] The majority of recipients who found work took jobs in low-paying sectors such as food service and child care, where Black and Latina mothers already were overly represented. For most parents and caregivers who had earnings in their first year after leaving TANF, those earnings were too low to lift their family out of poverty.[158] Other researchers find that TANF has failed to substantially improve recipients’ income and financial well-being, even when they find increases in employment.[159]

The federal TANF statute’s work participation rate requires states to engage a set share of recipients in specified work activities for a set number of hours each week,[160] but policymakers deliberately embedded incentives in the requirement for states to serve fewer families, as they get credit toward the work performance measure for the amount by which their caseloads decline.[161] In response to these and other incentives, nearly all states adopted full-family sanctions, which cut off the whole family from assistance (including the children) when a parent didn’t meet the work requirement, sometimes permanently. TANF families, who already have few resources, experience increased hardship and sometimes fall deeper into poverty after being cut off due to sanctions. Research consistently finds that Black and Latinx TANF recipients are likelier to be sanctioned than white people.[162]

More than 2 million families have been cut off TANF due to work-related sanctions since 1997, when most states’ TANF programs started.[163] In fact, states primarily meet their work participation rate requirement by serving fewer families over time, not by engaging them in work activities. Thus, while the rhetoric of “welfare reform” focused on work and social obligations, the design of the TANF block grant and its work requirements have largely led to declining caseloads, regardless of the circumstances of those not served.

In giving states virtually unfettered flexibility over eligibility policies and requirements, TANF opened the floodgates for states to police or punish parents’ behavior. Some policies coerce or punish certain behaviors to “fix” cash assistance recipients to be better mothers. School attendance policies (so-called “learnfare”)[164] and health-related policies (“shotfare”) sanction families if their child isn’t regularly in school or isn’t immunized; 37 states still had learnfare policies on the books in 2019, while 24 states had immunization requirements. Family cap policies deny benefit increases to families that have another child while receiving cash aid in order to discourage women’s reproduction;[165] these policies have declined over the years but 11 states still have them. Other policies, like restrictions on what families can buy with their benefits (generally provided on an EBT card) and drug testing, presume the parents are already guilty of something and will make bad choices. With little evidence that many TANF families are using their EBT cards in these venues, EBT restrictions are a solution in search of a problem.[166]

Similarly, state TANF policies mandating drug testing and barring persons with drug-related felony convictions from benefits are based on stereotypes.[167] At least 12 states have instituted suspicion-based drug testing policies[168] for TANF applicants and recipients.[169] A review of some state laws found these policies identify very few people who actually test positive[170] and instead, they create another hurdle for families applying for assistance. Under the 1996 law that created TANF, people who have been convicted of a drug felony are not eligible for TANF or SNAP (an extension of the “war on drugs” policies, which disproportionally affected Black and brown communities), but states can remove or modify this ban. In the early 2000s the vast majority of states had either completely denied access to people with drug felonies or granted them eligibility under certain conditions. Fortunately, states have since moved away from these bans; only seven states still have full bans in TANF.[171]

Time limits on receipt of cash aid were a central issue in the “welfare reform” debate in the mid-1990s. Federal TANF law set a 60-month time limit on federally funded cash aid but states can set shorter time limits and 22 states have done so; Arizona has the shortest time limit at 12 months. Black and other families of color are disproportionally cut off due to time limits, research shows.[172]

One justification given for replacing AFDC’s matched federal-state funding structure with the TANF block grant was that as states helped families leave the program successfully, they could use their funding flexibility to invest the savings into work programs or work supports such as child care. But that is not what has happened. States have withdrawn spending from helping families meet their basic needs but have invested little of it in work activities, and after initial increases in TANF’s early years, states have not increased child care investments much either. Instead, many states have used these federal funds in a variety of areas they traditionally supported with state funds, including programs related to child abuse and neglect, pre-kindergarten, and even college scholarships. Moreover, unlike spending on cash assistance, spending in these other areas is often not targeted to families with the lowest incomes.

This flexibility gives states another incentive to institute punitive policies that keep benefits low, cut families off, or make it harder to get on the program in first place, since when fewer families claim monthly cash aid, states can use the savings to fund other priorities or to fill in budget holes. In 2019 states spent just $6.5 billion (21 percent) of their federal and state TANF funds on basic assistance, which include monthly cash aid for families, down from $14 billion (71 percent) in 1997. That amounts to a 71 percent decline, after adjusting for inflation. States’ withdrawal of funding from cash assistance has harshly affected Black families. States with larger shares of Black residents tend to spend smaller shares of their TANF funds on basic assistance.[173]

This nation’s history of exclusion, marginalization, and social and economic control of Black single mothers and their children has prevented cash assistance from serving as an effective anti-poverty program and continues to do so. When adults lose a job or experience some other crisis, they have only limited access to cash assistance. All children, but especially Black and brown children, need a strong set of antiracist economic supports for their long-term well-being. TANF has a role to play, but it must be reimagined.

Racial discrimination in employment, housing, education, and social programs has contributed to higher rates of poverty and insecurity among Black families and other families of color. Racism and low, unstable income contribute to toxic stress (the excessive or prolonged activation of the body’s “fight or flight” response) in children, research now shows.[174] Stress from racist experiences is associated with increased inflammation, which can lead to chronic disease.[175] Black and other parents of color constantly worrying about their ability to pay the rent or afford food cannot effectively buffer children from stresses caused by racism or deprivation; this persistent adversity can overload children’s bodies and minds, with negative long-term consequences for their health, education, and employment.[176]

Robust anti-poverty programs that boost income can promote stability, relieving parents’ stress and improving children’s academic, health, and economic outcomes, a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on reducing childhood poverty finds.[177] But those programs must be antiracist and ensure equitable access and supports for all families.

Other anti-poverty programs, like SNAP and refundable tax credits, have grown significantly and have had a tremendous impact on reducing hardship, especially for Black and Latinx families and individuals.[178] Yet families with little or no cash income still need monthly cash assistance to be more economically secure. They have needs that may vary month to month — diapers, period products, personal hygiene and cleaning supplies, and utilities, for example — and that only cash can cover. Providing adequate, unconditional cash assistance also affirms the dignity of parents and caregivers and presumes they know how to best care for their children.

A reimagined TANF program also could complement a permanent extension of the American Rescue Plan’s temporary Child Tax Credit expansion.[179] An expanded Child Tax Credit would give households with low or moderate incomes additional resources to cover the expenses associated with child-rearing. But when a family falls on hard times, they need additional cash assistance from TANF to prevent a downward spiral that can result in eviction and homelessness among other negative outcomes. Together, an expanded Child Tax Credit and TANF could provide meaningful cash resources for families to cover their monthly essentials and maintain economic stability when their other income drops or is very low.

In short, cash assistance for when families experience a crisis needs to be a critical component of our economic support system. However, TANF, with its history of anti-Black racism, must be fundamentally reformed by adopting a Black Women’s Best framework. Black mothers need a cash program that provides stability through life’s challenges, protects their children from hardship, and affirms and supports parents’ autonomy over their families and careers. When this is available to Black mothers, it will mean that we have crafted a TANF program that works well for all families facing significant economic distress.

This work cannot be left entirely to the states; federal changes are essential to advance racial equity nationally and ensure a stable economic foundation for all families.

For a reimagined TANF program, we envision:

- Establishing a federal minimum benefit so that no family of any race falls below a certain income level. TANF benefits vary greatly by state and the lowest benefits tend to be in Southern states, which have larger Black populations and deeper-seated legacies of enslavement and Jim Crow. A minimum federal benefit would establish a necessary floor to mitigate these disparities and better protect Black, brown, and white families.

- Barring states’ mandatory work requirements. Conditioning benefits on participation in mandatory work programs is one of TANF’s most racially driven policies, one that started with enslavement and continued with coerced labor practices that continued long beyond emancipation. Federal policymakers should eliminate federal requirements that states impose sanctions and mandate participation in work activities. To ensure that states don’t maintain these policies even without a federal requirement, federal policymakers also should bar states from imposing mandating work as a condition of eligibility for cash assistance and imposing sanctions for non-participation.

- Barring behavioral requirements, time limits, other eligibility exclusions. Rooted in racism and sexism, these provisions demean families by assuming that adults are irresponsible and do not want what is best for their families. Worse, they often take away assistance from families that need it. Some also disproportionally hurt Black women and Black families. Eliminating them would remove the concept of “deservingness” from a program that should be designed to support parents and protect children from destitution.

- Refocusing TANF agencies on helping families address immediate crises and improving long-term well-being. TANF is better suited than other economic security programs to provide the support that parents need to achieve the goals they set for themselves and their families. (For example, tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit or the Child Tax Credit cannot provide services to families.) Yet it must do a much better job of helping families in crisis address their immediate needs and setting them up for long-term stability. The program should move away from mandatory work programs that do very little to help mothers find work that lift them and their children out of poverty and toward voluntary support programs that align with a family’s goals and needs. Resources that TANF agencies previously used to monitor compliance with mandatory work requirements could instead support families in new and meaningful ways.

- Changing TANF’s funding structure to retarget TANF resources to basic assistance, address funding inequities, and prevent erosion over time. States have used TANF resources to pay for other things beside cash aid to families; notably, states with high Black populations tend to spend less on basic assistance and to redirect these funds elsewhere. Federal policymakers based the original TANF block grant allocation on states’ AFDC spending amounts; this approach locked in some of the lowest TANF funding levels per poor child, for states where Black children disproportionately live.[180] Furthermore, the original block grant formula has lost about 40 percent of its value since its creation due to inflation, which makes it harder for states that want to adequately invest in families to do so. Federal policymakers should require states to spend a greater share of TANF resources on basic assistance, establish an equitable formula allocation, and increase the TANF block grant and index it to inflation to encourage states, especially those with lower benefits and higher Black populations, to increase benefits and serve more families.

Remaking cash assistance requires undoing the consequences — and power — of racist ideas and policies that have marginalized mothers and their families, Black people especially. A cash aid program that centers equity for Black women would, as the “Black Women Best” framework posits, promote the economic security of all families with the least income.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

| |

Total for which race of mother was reported |

White |

Black |

Percent Black |

Other* |

Black Families in areas reporting (1930 Census) |

| Alabama |

No program in 1931 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Alaska |

No program in 1931 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Arizona |

Mothers' race not reported |

|

|

|

|

|