BEYOND THE NUMBERS

A combination of factors has created an urgent need for federal policymakers to act soon on tax policy legislation:

- Costly, regressive tax cuts enacted during the George W. Bush and Donald Trump administrations have suppressed federal revenue and widened inequality.

- Even as millions of people whose incomes come mostly from wages and salaries file their annual tax returns this month and pay tax on this income, many of the nation’s wealthiest people will once again not have to pay income tax on a major source of their income: unrealized capital gains.

- The U.S. recently joined more than 130 nations in signing a milestone agreement to impose a global minimum tax aimed at stemming the flow of corporate profits to foreign tax havens, and Congress should revise the U.S. tax code to fully implement the new tax.

- This year’s difficult tax filing season, in which the IRS is trying to cope with millions of new returns while addressing a large backlog of unprocessed returns and filer correspondence, is the latest reminder that the IRS needs to be rebuilt after a decade of funding cuts.

The legislative clock is ticking, as Congress has critical work periods coming up before both the Memorial Day and July 4th recesses. The charts below show why lawmakers need to approach these work periods with greater urgency on tax policy.

Strengthening Federal Revenues

The large tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2017 weakened the federal revenue base. In 2019, before the pandemic and recession, revenues stood at just 16.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), down from 20 percent of GDP in 2000. (Those two years are comparable because both represent a peak in the business cycle.) While revenues have more recently risen to just over 18 percent of GDP as a result of the strong economic growth coming out of the recession, they remain insufficient to meet the nation’s investment needs, from helping families and children thrive and promoting broadly shared growth to supporting an aging population and the rising cost of health care.

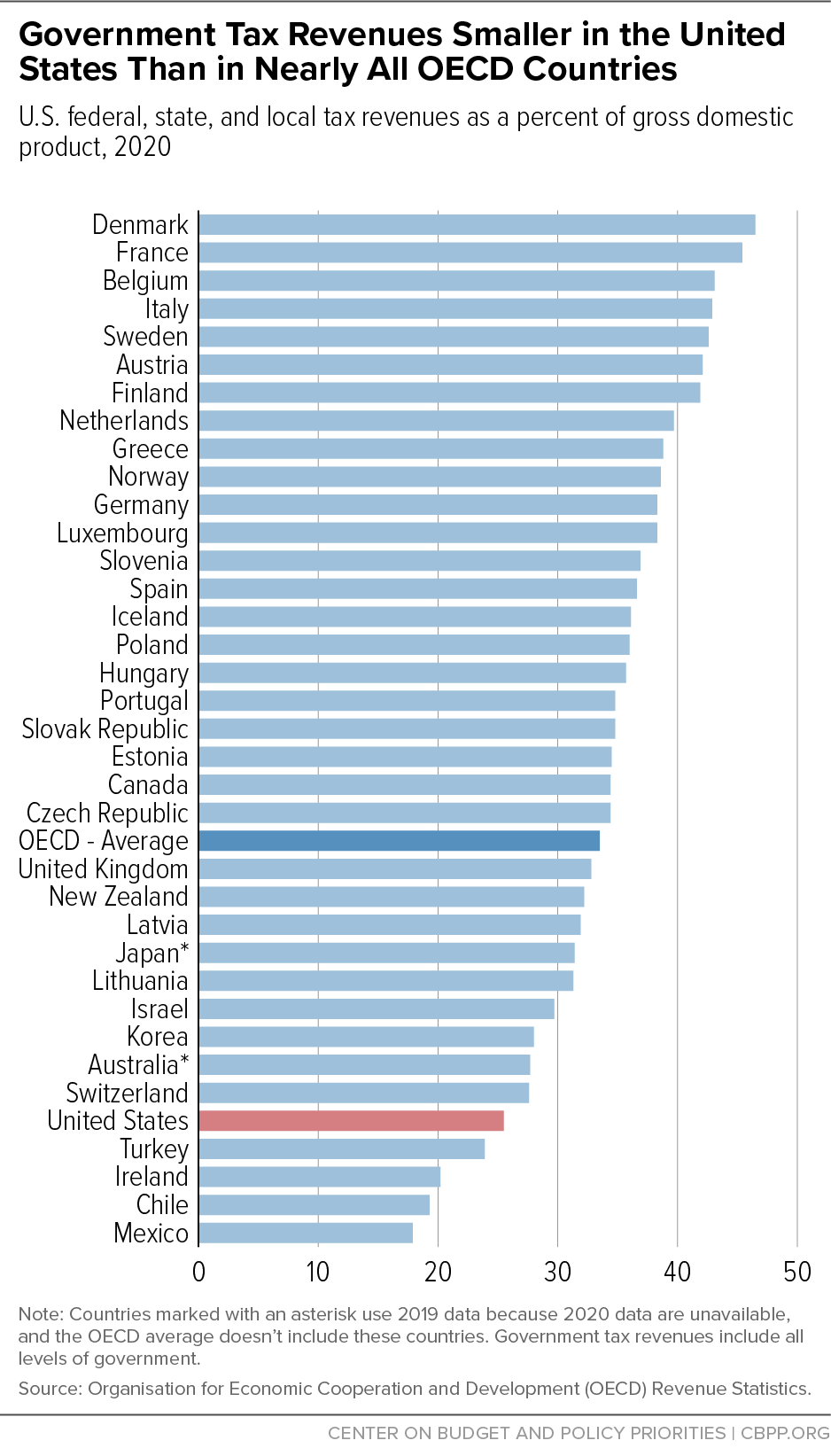

Moreover, the United States collects less in total federal, state, and local tax revenues than nearly every other developed country when measured as a share of the economy, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). By this standard, the United States has considerable room to raise more revenue.

Study after study has shown tax cuts tilted to high earners — like those enacted during the Bush and Trump administrations — to be an economic and fiscal failure. One global study, for example, concluded that reducing taxes on the rich “do[es] not have any significant effect on economic growth and unemployment”; instead it “lead[s] to higher income inequality.”

Ensuring That Wealthy People Pay Fairer Share of Tax

A major reason why the federal revenue base is weak is the large tax advantages that wealthy individuals and corporations enjoy. As a blockbuster investigation from ProPublica showed, some of the wealthiest people in the country often pay little or no individual income tax, which is the largest source of federal revenue and is designed to be progressive (meaning people with higher incomes should pay a larger share of their income in taxes). That’s because their income consists mostly of capital gains on their stocks and other assets, and no tax is due on those gains until they are “realized,” usually when the assets are sold. And if they die without selling the assets, the taxes on these “unrealized” capital gains are simply erased.

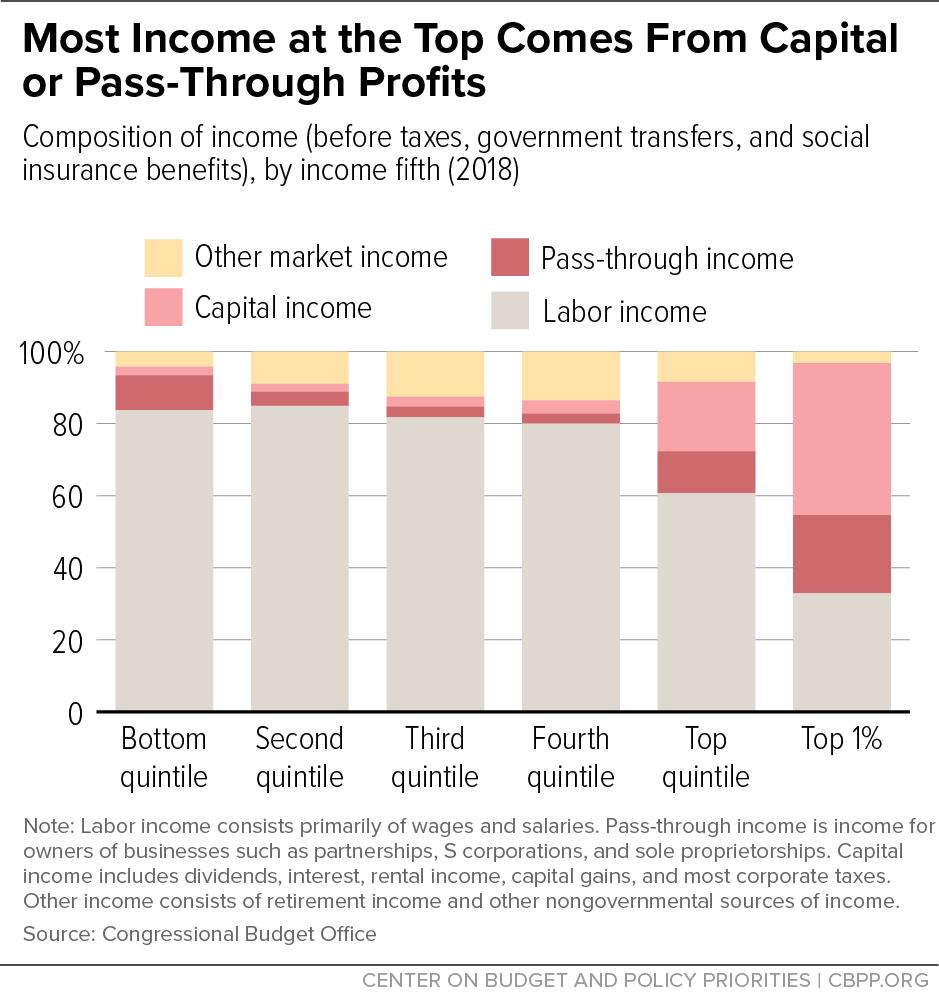

Wealthy people also often enjoy special tax rates and discounts on the part of their income that is taxable. People in the top 1 percent get most of their taxable income not from wages or salaries but from sources such as realized capital gains, dividends, and pass-through businesses.

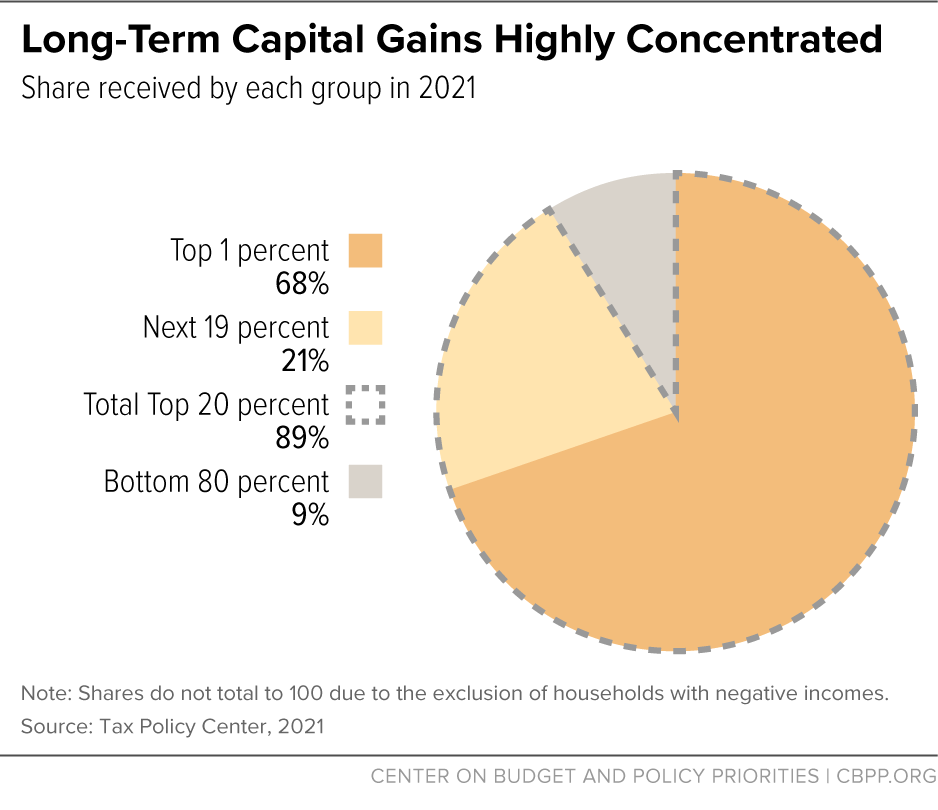

Capital gains income is highly concentrated — 68 percent flows to the top 1 percent of people — and benefits from a special low rate. The underlying capital gains rate is just 20 percent, compared to the 37 percent top rate on salaries.

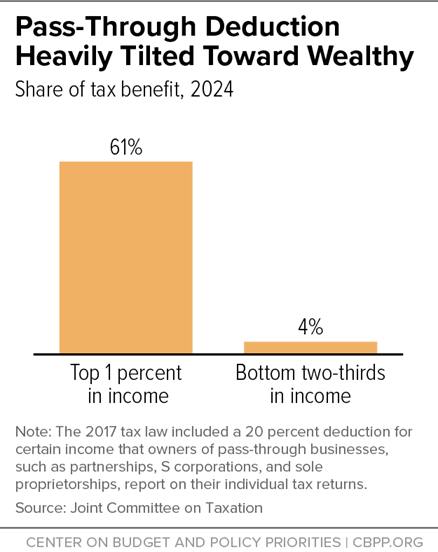

Pass-through income is also highly concentrated — around 70 percent of the income of partnerships, a common pass-through structure, flows to the top 1 percent — and enjoys special tax breaks. It not only is allowed to “pass through” the corporate income tax, thereby completely avoiding business-level taxation, but also often qualifies for a 20 percent deduction. Many tax policy experts across the political spectrum have widely criticized the deduction. Edward Kleinbard, former chief of staff at Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), termed it “Congress’ worst idea ever.”

Proponents of the 2017 law often identify small businesses as the deduction’s intended beneficiaries, but in reality, it is heavily tilted to the wealthy and big business: 61 percent of its benefits will go to the top 1 percent of households in 2024, JCT estimates. Many large, profitable businesses are structured as pass-throughs — including financial firms such as hedge funds and private equity firms, real estate businesses, oil and gas companies, and large multinational law and accounting firms — and they generate most pass-through income.

Major legislation the House passed last year didn’t make more of the income of the wealthiest taxable, raise the underlying capital gains and dividends rate, or do away with the pass-through deduction. But it did include a high-income surtax of 5 percent on household incomes — including capital gains, dividends, and pass-through income — over $10 million and an additional 3 percent tax on households with incomes over $25 million. Lawmakers should look to improve this proposal, such as by lowering the income thresholds, and enact it into law.

The President’s 2023 budget would require taxpayers with more than $100 million in wealth to pay at least 20 percent of their income, including their unrealized capital gains, in tax each year. The wealthiest people thus would pay a minimum amount of income taxes each year on their main source of income, just as millions of wage and salary earners already do. This proposal would take an important first step toward addressing a glaring and long-standing flaw in the tax code.

Requiring Corporations to Pay Fairer Amount of Tax on Global Profits

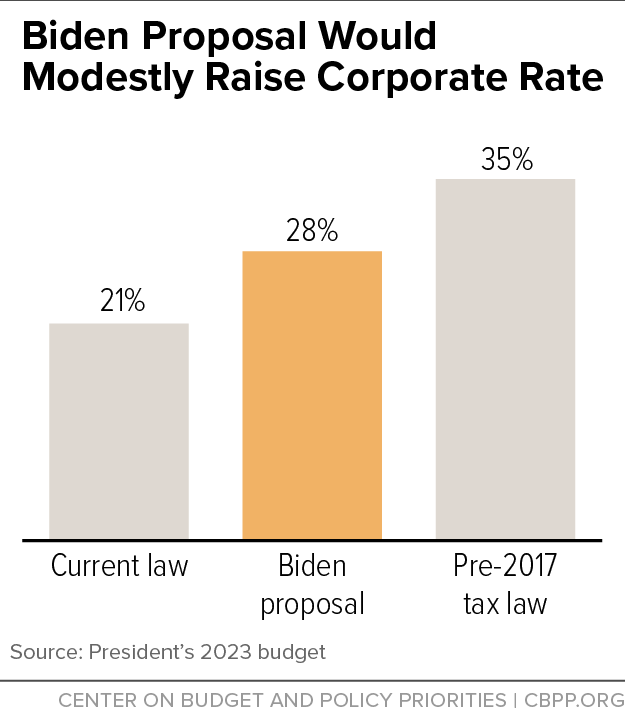

The 2017 tax law dramatically reduced the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, primarily benefiting corporate shareholders. The ownership of corporate shares — as with other kinds of wealth — is highly concentrated at the top and becoming more so. “The wealthiest 0.1% and 1% of households now own about 17% and 50% of total household equities, respectively, up significantly from 13% and 39% in the late 1980’s,” according to Goldman Sachs senior economist Daan Struyven. President Biden has proposed modestly raising the corporate rate from 21 percent to 28 percent, still well below the earlier 35 percent rate.

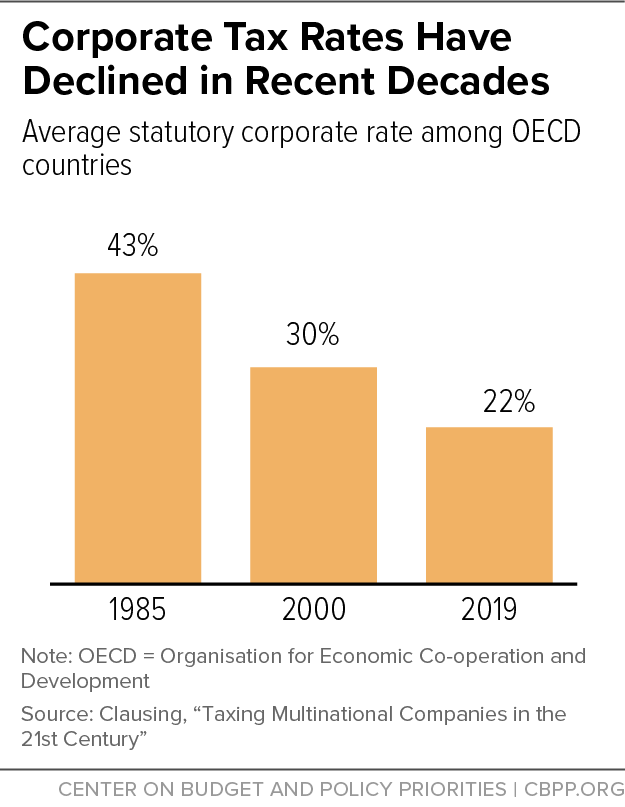

Corporate tax rates have declined steadily in recent decades among OECD countries, from an average statutory tax rate of 43 percent in 1985 to just 21.7 percent in 2019. In this corporate tax “race to the bottom,” countries have lowered their tax rates to attract companies (and tax revenue) at the expense of other nations.

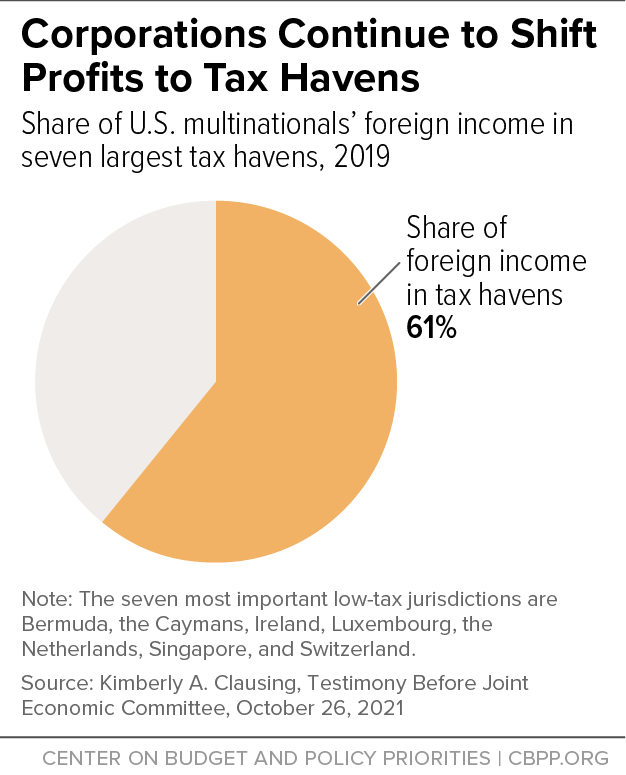

Multinational corporations also avoid U.S. tax on large amounts of their income by shifting profits overseas to low-tax countries, or tax havens. The 2017 tax law made some changes to the international tax regime but didn’t address the large incentives multinationals have to shift profits, investments, and operations overseas. Corporate profit shifting remains a major problem, with 61 percent of U.S. multinationals’ foreign profits “booked” in the seven most prominent tax havens.

Following a major push by the Biden Administration, more than 130 countries representing more than 90 percent of the world’s economy agreed in October 2021 to enact major international tax reforms aimed at thwarting the twin problems of profit shifting and the corporate tax race to the bottom. A key feature of the agreement is a 15 percent global minimum tax on companies’ foreign profits. This minimum tax includes certain features that are stronger than the existing U.S. minimum corporate tax — the tax on global intangible low-taxed income or GILTI, established by the 2017 tax law.

The House-passed bill and the Biden Administration’s 2023 budget include several provisions to align the U.S. more closely with the deal, such as raising the tax rate on foreign profits to 15 percent (from 10.5 percent) and requiring corporations to calculate the minimum tax in each country in which they operate instead of an aggregate global basis. Policymakers should enact these provisions, which would raise significant revenue to invest in urgent national priorities while positioning the United States as a leader in global tax negotiations.

Rebuilding the IRS

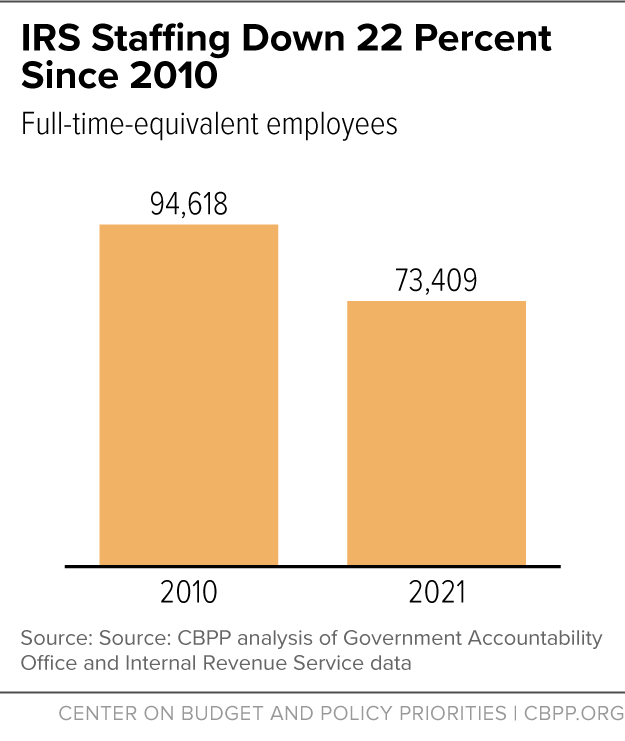

The IRS is responsible for helping taxpayers navigate the tax system and enforcing the nation’s tax laws in order to collect the taxes needed to fund national priorities. But funding cuts have significantly undermined its capacity to fulfill these core roles. Tasked with processing a steadily growing number of tax returns and now facing added administrative challenges due to the pandemic, the IRS is in a depleted state. Its overall budget was repeatedly cut in real terms over the last decade and remains roughly 20 percent below its 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation.

Because of these funding cuts, the agency has lost more than one-fifth of its staff and can’t even answer most taxpayers’ phone calls.

As the National Taxpayer Advocate noted recently: “In FY 2019, the most recent pre-pandemic year, the IRS received almost 100 million telephone calls, and CSRs [customer services representatives] answered just 29 million. That is simply a resource issue. Additional technology resources and more employees are required if the IRS is going to answer more telephone calls.” The situation has only deteriorated in the last couple of years due to the pandemic.

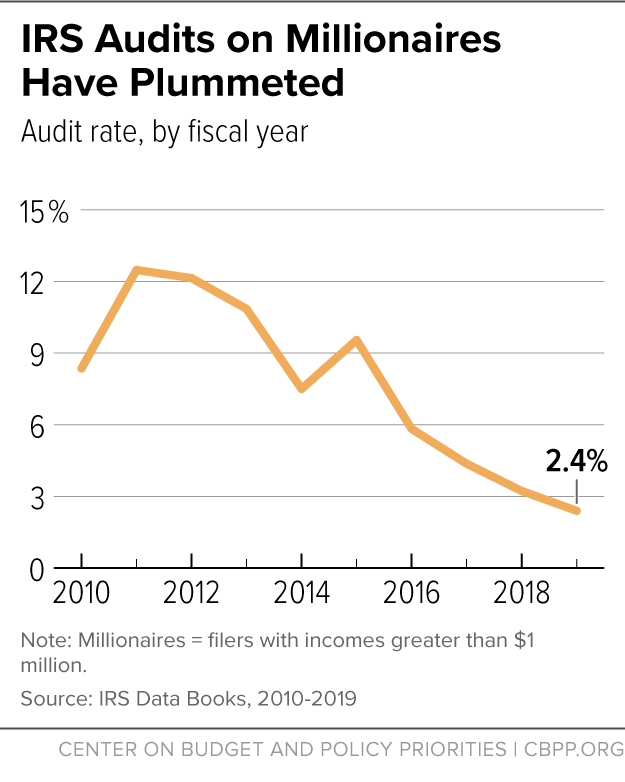

Tax enforcement has also suffered. The IRS enforcement division was cut 24 percent between 2010 and 2022, after adjusting for inflation, and its staff has fallen by 29 percent, even after a small increase in 2020. Worse still, the number of revenue agents — auditors uniquely qualified to process the complex returns of high-income individuals and corporations — fell by 40 percent between 2010 and 2020, to levels not seen since 1954. As a result, audit rates of high-income people have plummeted.

The IRS desperately needs a rebuild — to modernize its computer systems, improve customer service, and collect more of the nearly $600 billion in legally owed taxes that go uncollected each year. The Biden budget proposes to increase IRS appropriations by 12 percent over the 2022 level, which would help the agency as it begins rebuilding after a decade of cuts. But considerably more would be needed to return funding to the 2010 level after adjusting for inflation. The House-passed legislation includes a separate $80 billion in mandatory funding over ten years to provide the predictable, sustained funding the IRS needs over several years to help the agency rebuild its audit staff and make long-term commitments to technology upgrades. It is critical that this funding become law.