- Home

- Federal Tax

- Congress Needs To Take Two Steps To Fund...

Congress Needs to Take Two Steps to Fund the IRS for the Short and Long Term

Over the next several weeks, Congress has two important opportunities — in negotiating appropriations for fiscal year 2022 and a compromise agreement on Build Back Better — to put the IRS on a path to a much needed, and long overdue, rebuild after years of crippling funding cuts. Those cuts, aggravated by new challenges posed by the pandemic, have helped create what one recent news report termed a “brutal filing season” this year as the IRS tries to address a large backlog of unprocessed returns and filer correspondence despite its shrunken funding.[1] Over the longer term, the cuts risk undermining the IRS’ ability to perform the basic function of government for which it is responsible. Congress should respond by:

- Funding the President’s full request for 2022 IRS appropriations. President Biden’s fiscal year 2022 budget proposed increasing IRS appropriations by 14 percent over the 2021 level,[2] including a 15 percent increase for customer service. But the IRS has been operating under a stopgap funding measure since the fiscal year began on October 1, which freezes IRS (and most other) funding at the 2021 level. The current continuing resolution expires on February 18, so Congress must act soon to address funding for the rest of the fiscal year. Both the House-passed Financial Services appropriations bill and the bill proposed by Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy provide the President’s full requested increase for the IRS for 2022. Congress should retain those IRS funding levels as part of any agreement on final 2022 appropriations.

- Retaining the President’s full long-term IRS funding proposal in any final Build Back Better agreement. The House-passed Build Back Better legislation would provide roughly $80 billion in mandatory funding over ten years to give the IRS the predictable, sustained funding it needs over several years to rebuild its depleted staff, make the long-term commitments needed to upgrade its severely outdated computer systems, and address the large “tax gap” — the nearly $600 billion of legally owed taxes that go unpaid each year. This measure enjoys strong support among Senate Democrats. While it is clear that the House version of Build Back Better will ultimately need to be revised to pass the Senate, the IRS funding should be considered an essential element of any final bill.

These steps would make important progress toward the ultimate goal of a rebuilt IRS that restores public trust in the fairness of the tax system by responding in a timely, effective manner to taxpayer questions and enforcing the nation’s tax laws fully so that everyone pays the taxes they owe, just as the vast majority of taxpayers and businesses do voluntarily.

Years of Cuts Have Depleted the IRS

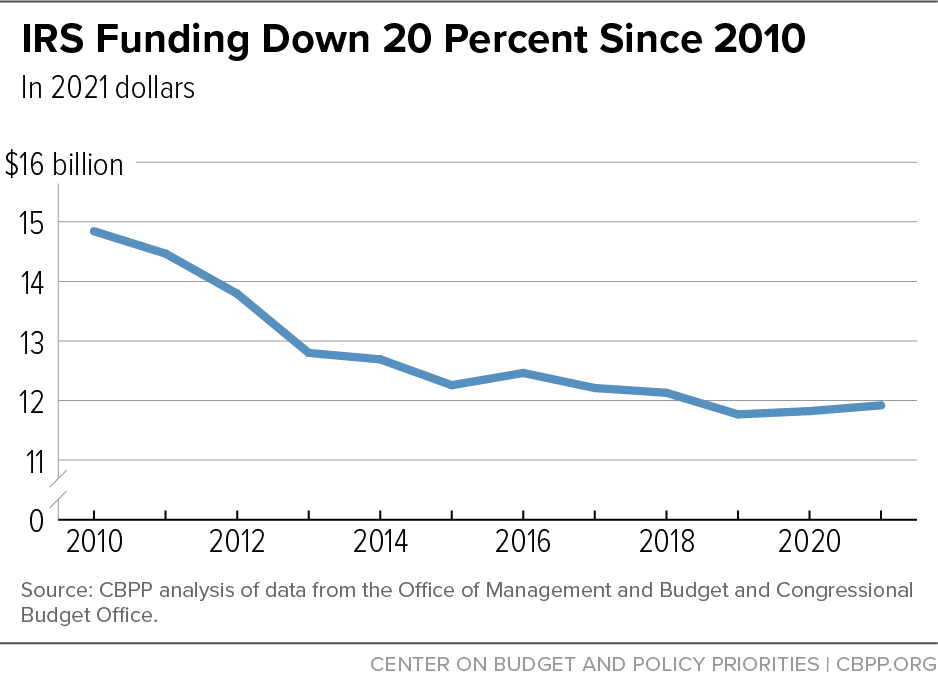

Tasked with processing a steadily growing number of tax returns over time and now in the midst of a pandemic-induced crisis period, the IRS is in a depleted state. Its overall budget was repeatedly cut in real terms over the last decade and remains roughly 20 percent below its 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation. (See Figure 1.)

This funding decline has significantly undermined the agency’s capacity to fulfill its core responsibilities of helping taxpayers navigate the tax system and enforcing the nation’s tax laws. Without robust funding, the IRS will lack the resources to do its job and collect the taxes needed to fund national priorities.

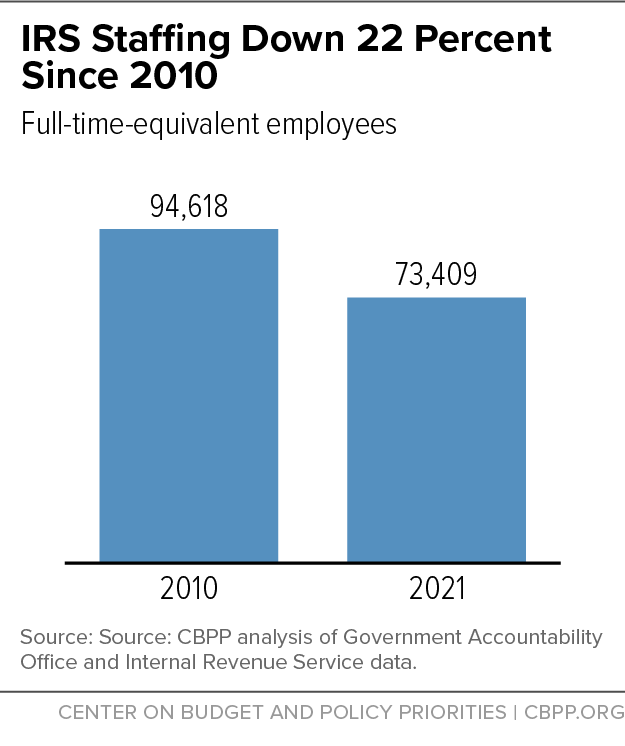

As a result of these funding cuts, the agency has lost more than a fifth of its staff. (See Figure 2.)

Insufficient funding has even made it hard for the IRS to answer most taxpayers’ phone calls. As the National Taxpayer Advocate noted in a recent report:

In FY 2019, the most recent pre-pandemic year, the IRS received almost 100 million telephone calls, and CSRs [customer services representatives] answered just 29 million. That is simply a resource issue. Additional technology resources and more employees are required if the IRS is going to answer more telephone calls.[3]

The IRS enforcement division has faced the deepest cuts: its budget was cut 23 percent between 2010 and 2021, after adjusting for inflation, and its staff has fallen by 31 percent, even after a small increase in 2020. Worse still, the number of revenue agents — auditors uniquely qualified to process the complex returns of high-income individuals and corporations — fell by 40 percent between 2010 and 2020, to levels not seen since 1954.[4]

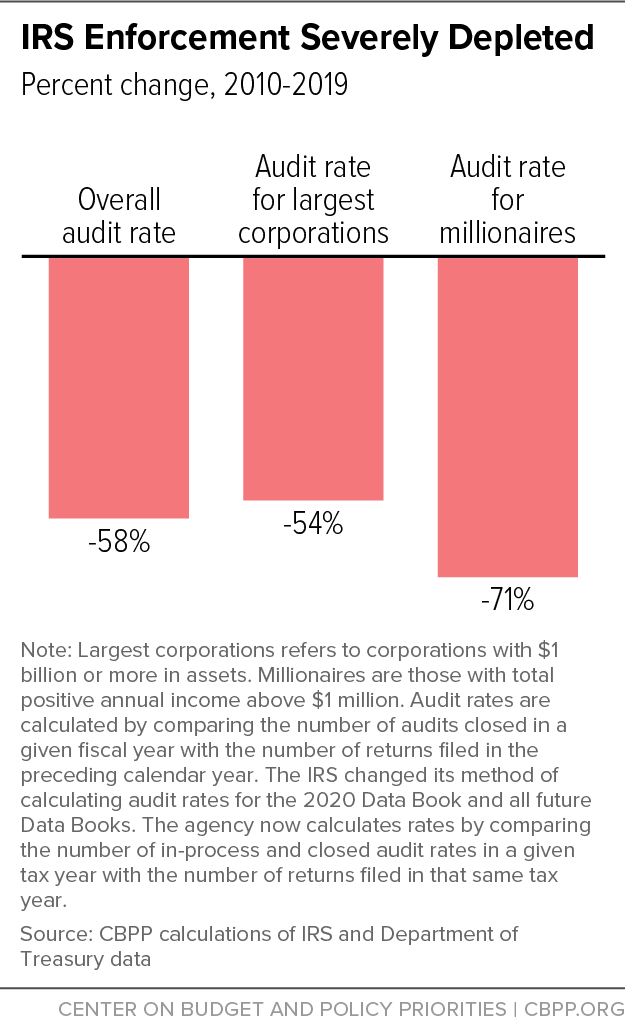

Auditing, particularly of the most complex returns, remains labor intensive. Largely as a result of funding cuts and declining audit staff, the overall audit rate fell by 58 percent between 2010 and 2019, the last year comparable data are available. Over the same period, the audit rate on large corporations fell 54 percent, and audits on millionaires plummeted 71 percent. (See Figure 3.)

The pandemic highlighted and worsened the fragile state of the IRS. As the National Taxpayer Advocate explained:

[B]ecause the IRS had been functioning under subsistence-level budgets for years . . . it had not outfitted many of its employees with laptop computers or otherwise established the infrastructure that would enable CSRs to telework and continue providing telephone assistance. Instead, the IRS telephone lines either were vastly understaffed or in some cases shut down completely.[5]

The IRS also assumed added responsibilities as part of the federal government’s response to the pandemic, providing rounds of stimulus payments and monthly Child Tax Credit deposits — both of which provided a financial lifeline to millions of people across the country. IRS employees performed exceptional work under trying circumstances, but neither the state of the agency’s technology nor the size of its workforce should have been allowed to deteriorate to such low levels.

Two Important Steps to Rebuilding the IRS

The President’s 2022 budget prioritized rebuilding the IRS, and the budget resolution that Congress adopted for 2022 was designed to facilitate adoption of the Biden proposals. Currently, the IRS is funded almost entirely by annual appropriations,[6] and they should remain the foundation of the IRS budget and a key part of any plan to rebuild and modernize the agency. However, the President and key members of Congress recognized that the annual appropriations process alone can’t fully address the IRS’ funding shortfall because of the shortfall’s size and the need for predictable, sustained funding over several years. Rebuilding the agency, therefore, will require a two-pronged approach.

Funding President’s Full Request for 2022 IRS Appropriations

The President requested a $1.2 billion (10 percent) increase in base IRS funding for 2022, including a $385 million (15 percent) increase in customer service funding. While not enough to return funding to 2010 levels after adjusting for inflation, the increases would significantly help the agency as it begins rebuilding.

The President also requested an additional $417 million for enforcement and related purposes through an “allocation adjustment” mechanism. The congressional budget resolution authorized this adjustment, allowing the $417 million to be provided outside the limits that the resolution sets on overall appropriations. (Similar allocation adjustments have been used for many years for program integrity purposes involving Medicare and other health programs, disability benefits, and unemployment compensation. They have also been used from time to time for the IRS.) When the allocation adjustment is added in, the requested increase for the IRS in 2022 becomes $1.655 billion (14 percent). The 2022 Financial Services appropriations bill passed by the House last summer includes the full requested increase. The Senate has not taken up a Financial Services bill, but a version proposed by Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy provides the same increases as in the President’s request and the House-passed bill.

However, we are a third of the way into fiscal 2022, and the IRS is still operating under continuing resolution (CR) funding levels — effectively a freeze at the 2021 levels. With the current CR expiring on February 18, bipartisan negotiations are underway to find agreement on full- appropriations funding. Such an agreement would likely provide higher funding for defense, and lower funding for non-defense programs, than the President proposed and the House bills reflect.[7] But even if a final agreement embraces lower non-defense levels, Congress should continue to prioritize the President’s full request for the IRS — both the regular 2022 appropriations and the allocation adjustment amount — in order to make progress on the IRS funding shortfall.

Retaining Full Long-Term IRS Funding Proposal in Final Build Back Better Agreement

The President’s 2022 budget included, in addition to the increased IRS appropriations discussed above, $72.5 billion in mandatory funding for rebuilding the IRS. This mandatory funding would give the IRS the certainty it needs to rebuild its staff (especially its hardest-hit enforcement staff), make longer-term investment commitments in technology, and address the tax gap, which now exceeds $574 billion annually, according to former IRS commissioner Charles Rossotti.[8]

The House-passed Build Back Better legislation includes an IRS mandatory funding provision similar to the President’s budget proposal, including $45 billion for enforcement, $27.4 billion for operations support, $4.75 billion for technology modernization, and $2 billion for taxpayer service. The provision enjoys strong Senate Democratic support. While it is clear that the House version of Build Back Better will ultimately need to be revised to pass the Senate, the IRS funding should be considered an essential element of any final agreement.

End Notes

[1] Laura Weiss, “IRS budget in focus as brutal tax filing season arrives,” Roll Call, January 28, 2022, https://rollcall.com/2022/01/28/irs-budget-in-focus-as-brutal-tax-filing-season-arrives/.

[2] This increase includes both regular appropriations and the additional program integrity allocation adjustment described in this paper. Funding levels used in this paper do not reflect any supplemental appropriations made to the IRS for handling COVID-19 relief funding.

[3] National Taxpayer Advocate, “Annual Report to Congress 2021,” January 2022, https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ARC21_Full-Report.pdf.

[4] Data on revenue agent staffing levels are available only through fiscal year 2020. See SOI Databook Table 32, Personnel Summary, by Employment Status, Budget Activity, and Selected Personnel Type, Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020.

[5] National Taxpayer Advocate, op. cit.

[6] The IRS also collects some user fees and reimbursements and occasionally receives additional funding through legislation outside its annual appropriation, such as the funding it received through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to distribute Economic Impact Payments.

[7] For instance, Committee Chair Senator Patrick Leahy released proposed drafts of nine bills (those that had not yet been approved by the committee), and they would reflect somewhat lower funding for non-defense and higher defense funding than the House bills — although as noted above, the full funding for the IRS was protected. Jennifer Shutt, “Senate Democrats unveil remaining fiscal 2022 spending bills,” Roll Call, October 18, 2021, https://rollcall.com/2021/10/18/senate-democrats-unveil-remaining-fiscal-2022-spending-bills/.

[8] This figure likely understates the true size of the tax gap. According to current IRS commissioner Charles Rettig, the total value of uncollected taxes could reach $1 trillion or more annually. See Chuck Marr et al., “Rebuilding IRS Would Reduce Tax Gap, Help Replenish Depleted Revenue Base,” CBPP, April 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/rebuilding-irs-would-reduce-tax-gap-help-replenish-depleted-revenue-base.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: