- Home

- Federal Tax

- The Need To Rebuild The Depleted IRS

Chart Book: The Need to Rebuild the Depleted IRS

This chart book provides background on the depletion of the IRS. For more on how to rebuild the IRS, see: Rebuilding IRS Would Reduce Tax Gap, Help Replenish Depleted Revenue Base.

Introduction

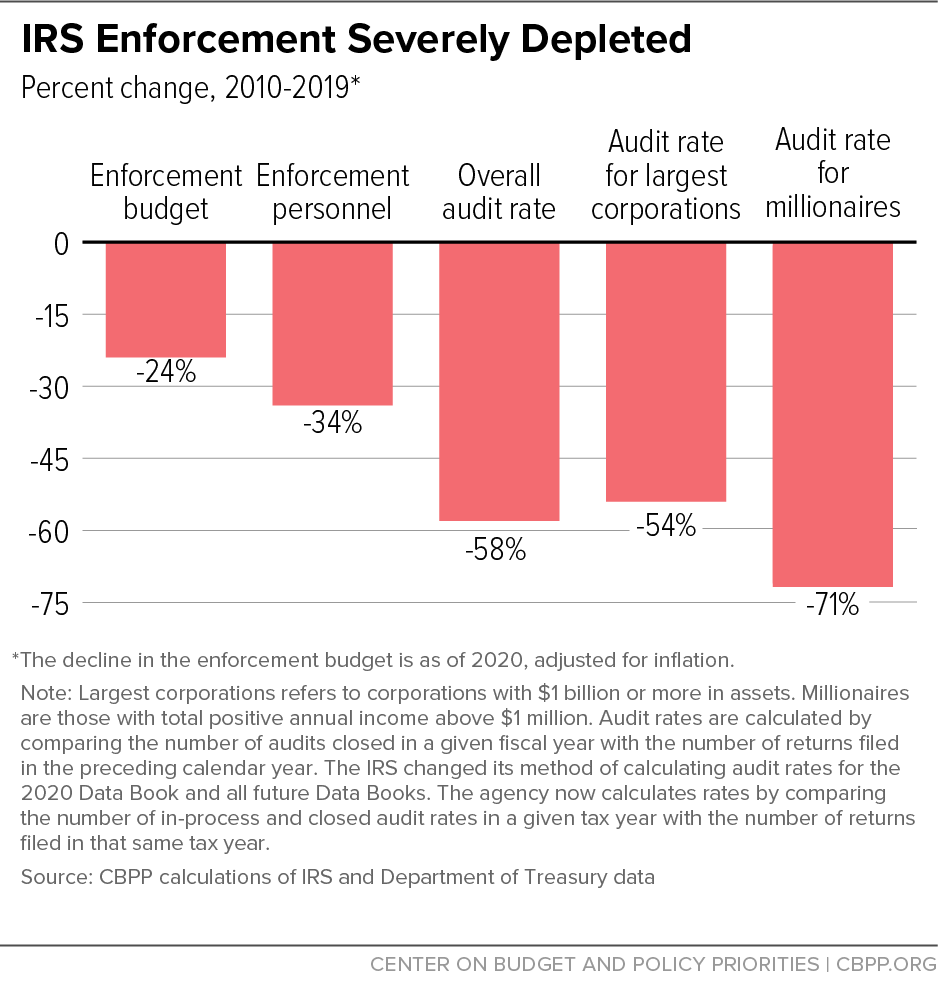

The IRS budget has been cut dramatically over the past decade, severely undermining the agency’s ability to perform its fundamental jobs of enforcing the nation’s tax laws and helping taxpayers navigate a tax system that relies on voluntary compliance. The agency’s workforce has been sharply reduced, and audit rates, especially for large corporations and high-income taxpayers, have plummeted. As a result, the tax gap — the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid — is large and growing.

the tax gap — the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid — is large and growing.As a central piece of the federal government’s infrastructure, the IRS needs to be rebuilt. A rebuilt IRS could help restore public trust in the fairness of the tax system by responding in a timely, effective manner to taxpayer questions and enforcing the nation’s tax laws fully so that everyone pays the taxes they owe, just as the vast majority of taxpayers and businesses do voluntarily. Moreover, a rebuilt and modernized IRS, combined with enhanced reporting requirements, would help restore the nation’s depleted revenue base — collecting taxes that are legally owed — to fund national priorities.

This chart book illustrates how the IRS, particularly its enforcement function, has been depleted, and details the pressing need to enact major legislation to rebuild.

- IRS Resources Are Depleted

- The IRS Can’t Perform Basic Government Functions

- The Amount of Unpaid Tax is Large and Growing

- Focusing on Low-Income Filers Is Unfair and Inefficient

- The IRS Can Be Rebuilt

I. IRS Resources Are Depleted

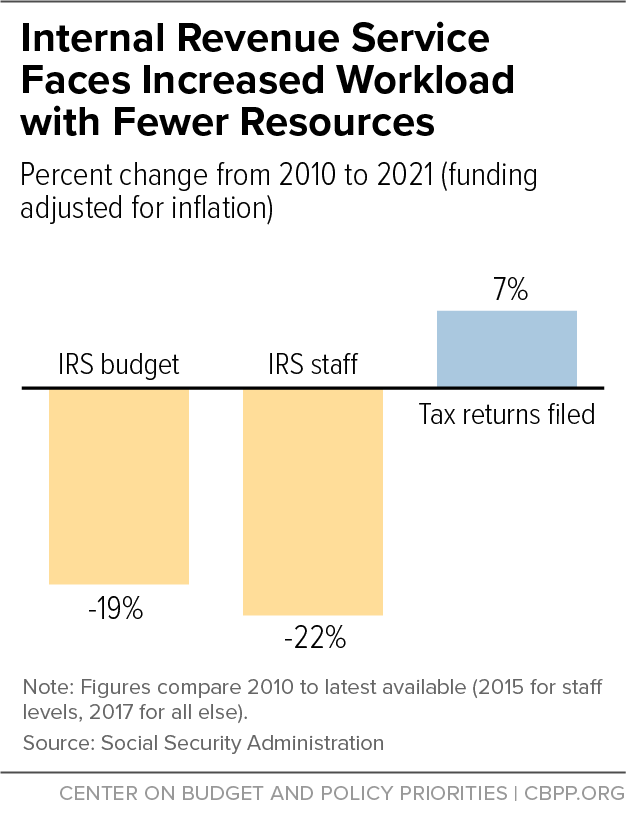

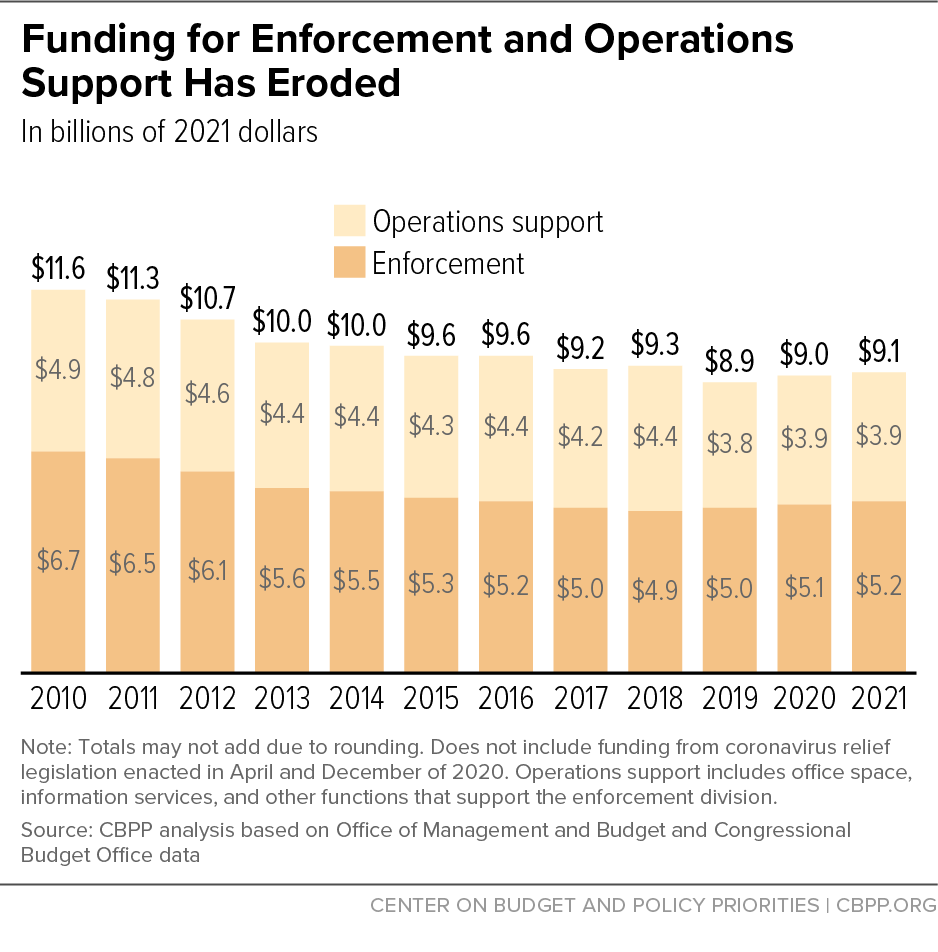

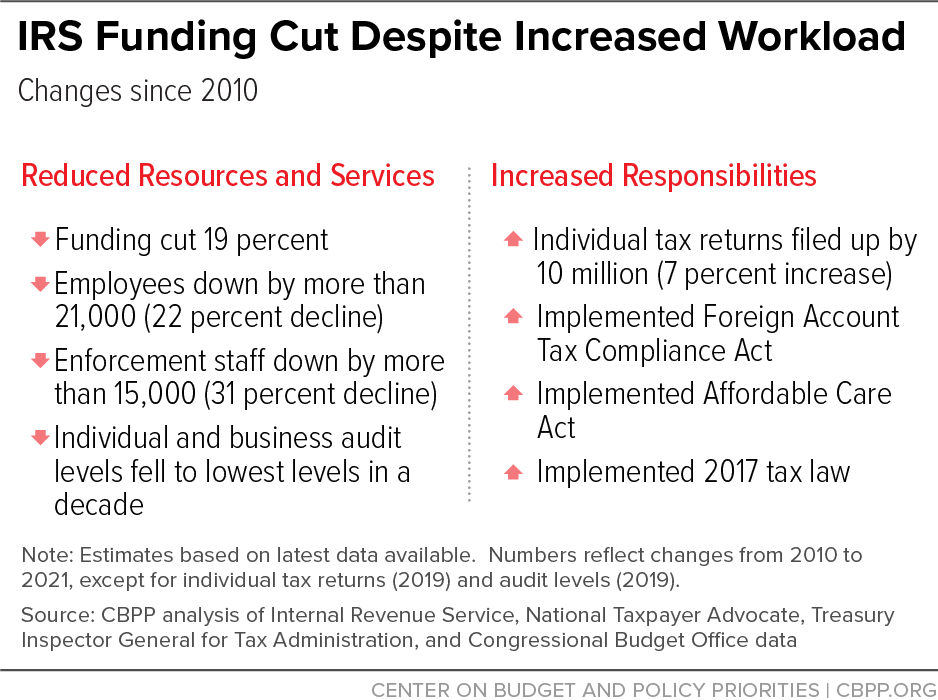

The IRS’ budget has been cut dramatically. Despite modest increases in the past few years, funding remains 19 percent below the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation.

In particular, funding has been cut in the enforcement and operations functions, which are vital for fair and efficient enforcement of the tax law.

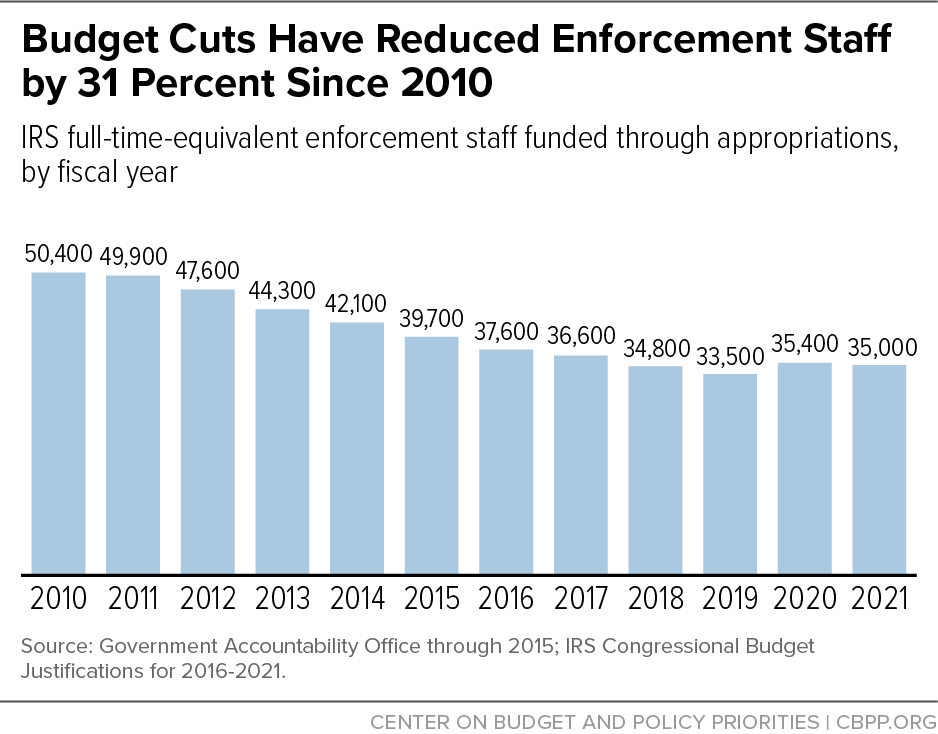

This decrease in funding has led to sharp reductions in the IRS workforce. The number of enforcement staff fell drastically between 2010 and 2019, and while 2020 saw slight improvements, there are still 31 percent fewer enforcement staff than there were in 2010. Worse still, the number of revenue agents — auditors who are uniquely qualified to process the complex returns of high-income individuals and corporations — has fallen by 39 percent, to levels not seen since 1954. To rebuild, the IRS needs resources to aggressively hire and train new agents, particularly given the high number of IRS employees eligible for retirement.

The IRS’ information technology systems are also sorely outdated. The agency needs state-of-the-art technology to perform its core functions of collecting taxes and enforcing the nation’s tax law, while countering sophisticated identity thieves and tax evaders.

II. The IRS Can’t Perform Basic Government Functions

As the IRS’ resources have dwindled, its workload has increased. Annual individual tax return filings have risen by nearly 10 million a year since 2010. Meanwhile, the IRS has been tasked with implementing multiple changes to the tax code, including premium tax credits and other Affordable Care Act tax changes, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, and the myriad complications the 2017 tax law introduced.

Auditing, particularly of the most complex returns, remains labor intensive. Largely as a result of funding cuts and declining audit staff, the overall audit rate has fallen by 58 percent since 2010.

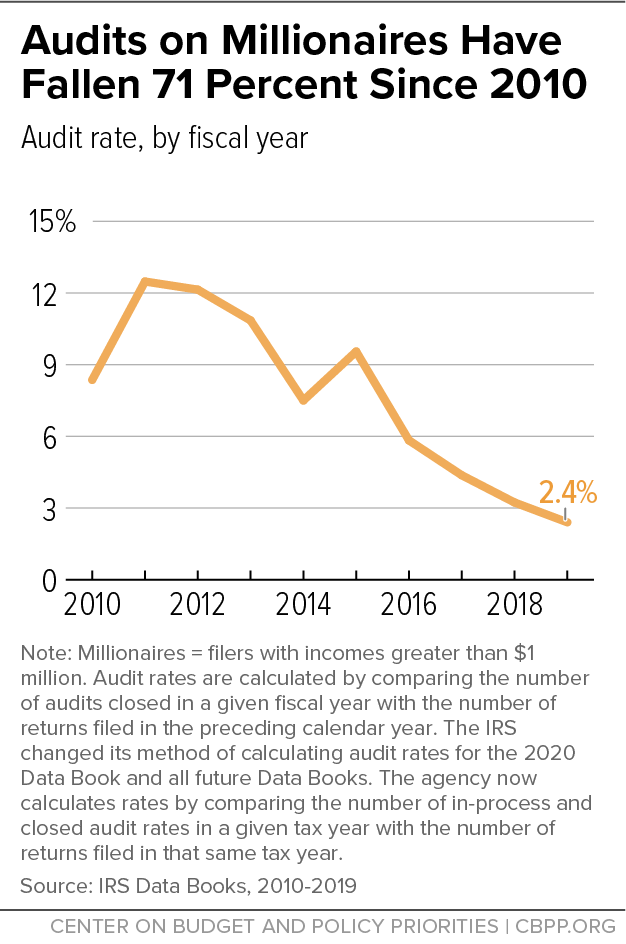

Over the same period, the audit rate on large corporations has fallen 54 percent, and millionaire audits have plummeted 71 percent.

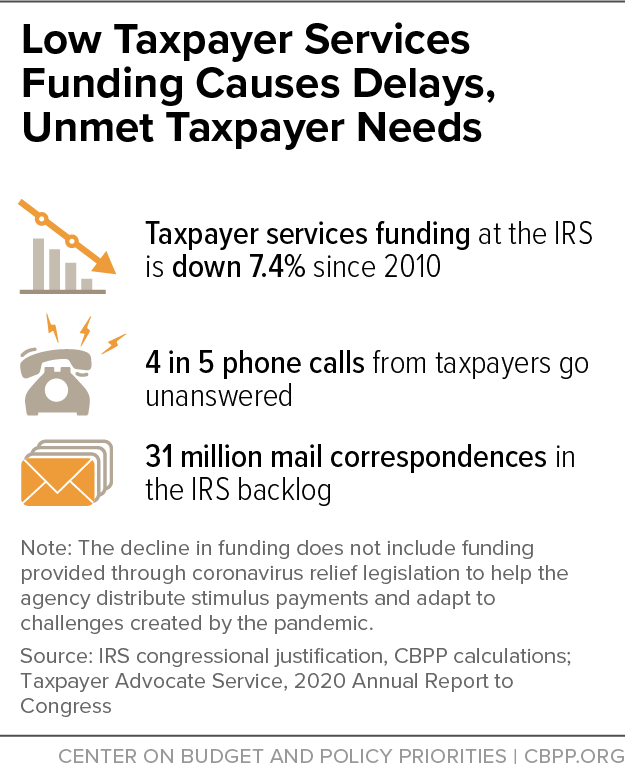

The effects of budget cuts can be seen across IRS functions. For instance, the decline in taxpayer services funding has led to the agency answering just 1 in 4 phone calls from taxpayers with questions, and those who do get through often do so after significant wait times. In May 2020, the IRS reported a backlog of 20 million mail correspondences, which likely delayed taxpayers’ receipt of their refunds and may have created penalties for those unable to respond to examinations or collection inquiries.

III. Amount of Unpaid Tax Is Large and Growing

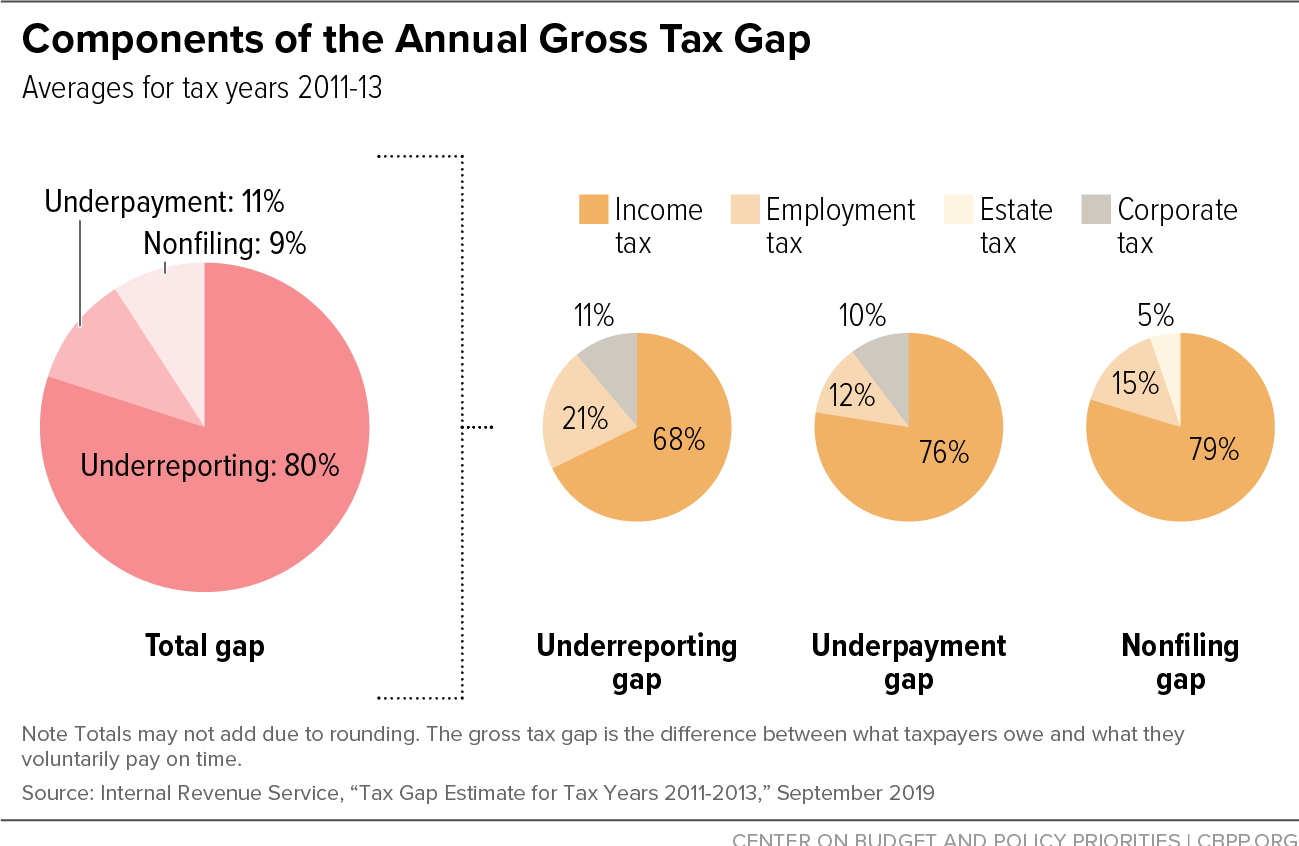

The IRS estimates the “gross tax gap,” the amount of tax that taxpayers do not pay voluntarily and on time. The most recent IRS estimate for the gross tax gap was $441 billion per year for 2011-2013. The “net tax gap,” which is the gross tax gap minus subsequent collections from enforcement and late payments, was $381 billion per year during this period. The Treasury Department has now extrapolated the net tax gap to amount to $584 billion in 2019 — and an estimated $7 trillion over the next decade.

But these estimates likely understate the size of the tax gap. IRS commissioner Charles Rettig recently testified that the tax gap could be close to $1 trillion today, given the rise of harder-to-trace income from digital currencies and offshore accounts.

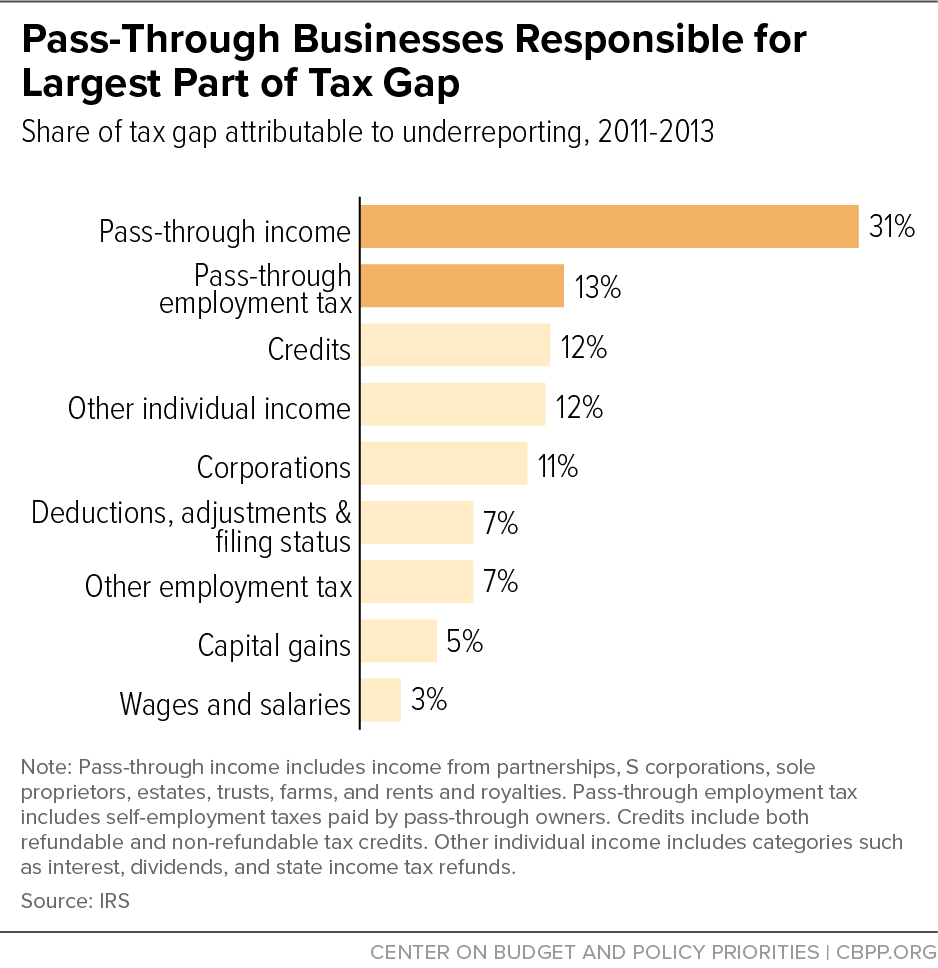

Similarly, new research from IRS and outside economists suggests that the extent of wealthy households’ tax evasion is considerably larger than existing IRS estimates. That’s because the IRS estimates the tax gap using data collected from random audits, which “do not capture most tax evasion through offshore accounts and pass-through businesses, both of which are quantitatively important at the top.” By more fully accounting for these types of tax evasion, the researchers estimate that the top 1 percent of individual taxpayers likely underreport around 20 percent of their income, far higher than IRS tax gap estimates suggest.

High-income individuals generally have the largest tax liabilities and thus the discrepancy between what is owed and what is paid is greater, as is their incentive to avoid and evade taxes. Moreover, the wealthy tend to have more complex returns, with income accruing in opaque categories not subject to the kind of information reporting known to promote compliance, including pass-through income (income from sources such as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships).

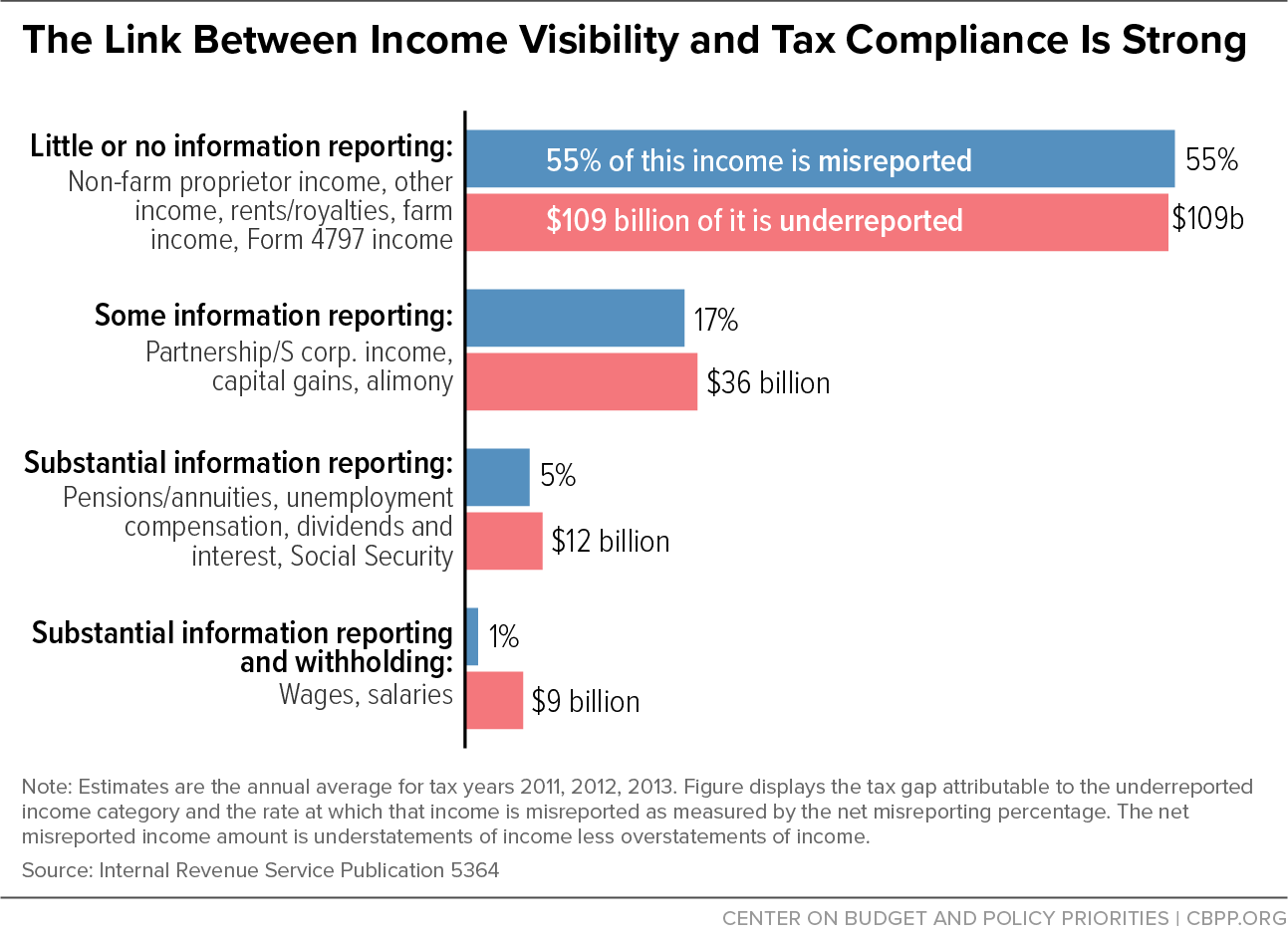

The IRS has noted that income from partnerships, S corporations, and capital gains are subject to “some” information reporting and that income from sole proprietorships is subject to “little or no” information reporting. Moving these income categories one step higher on the IRS scale could significantly help the agency track incomes that now are disproportionately underreported.

The tax gap’s single largest source is the underreporting of pass-through income. The IRS estimates, for example, that sole proprietors misreport a staggering 55 percent of their income. S corporations and partnerships also have a high misreporting rate of 17 percent. And while audits of higher-income individuals and businesses are costlier to undertake, they yield much larger average collections than those of lower-income taxpayers, a Congressional Budget Office report found.

IV. Focusing on Low-Income Taxpayers Is Unfair and Inefficient

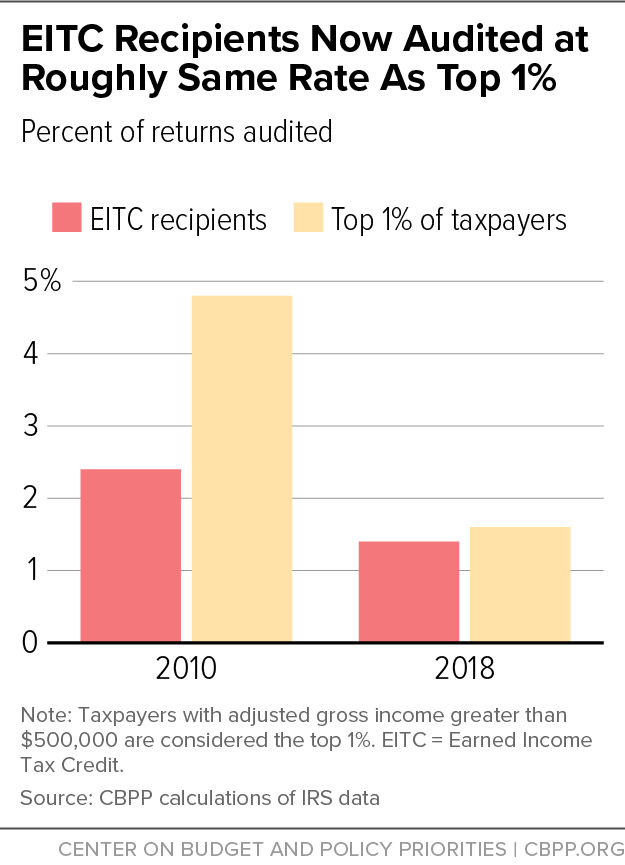

Audits of low- and moderate-income working people who receive the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) have declined alongside high-income audits, but at a much slower pace: they fell by about 40 percent between 2010 and 2018, versus by 67 percent for the roughly top 1 percent of filers. As a result, an EITC recipient is now about as likely to be audited as someone in the top 1 percent. This shift has occurred even though overpayments in the EITC, the main tax provision that prompts audits of low-income filers, make up only 6 percent of the tax gap. By contrast, as noted above, an increasing share of the tax gap is tied to tax avoidance and evasion by the wealthy.

Decisions about how to enforce the tax code may appear race neutral but can significantly affect racial inclusion and equity. Policymakers’ decisions about funding IRS enforcement, and tax administrators’ decisions about how to use scarce resources, can produce geographically and racially disparate audit rates.

Though the IRS does not publicly describe how it decides whom to audit, there may be several factors. Audits of high-income and corporate returns can be both time- and personnel-intensive for the IRS because of these filers’ complex financial affairs. This means that audits of high-income people may be particularly vulnerable to cuts when IRS funding is tight. By contrast, it costs relatively little for the IRS to conduct a “correspondence examination” of a low-income filer, requiring the filer to mail in relevant documents to prove eligibility.

In fact, Congress has called in the past for the IRS to increase scrutiny of EITC filers, who are disproportionately people of color. Congress also placed much less emphasis on oversight of tax breaks that benefit high-income filers and of areas of the tax code that comprise a much larger share of the tax gap, like pass-through business income, which disproportionately affect tax filers who are white.

As recently as 2015, for example, policymakers made permanent important expansions in the EITC and enacted provisions intended to reduce improper payments of the EITC, including requiring the IRS to hold tax refunds until February 15 if the household’s tax return included an EITC claim. By contrast, and reflecting this double standard, as part of the 2017 tax law, policymakers enacted a costly new 20 percent tax deduction for pass-through business income, which was not accompanied by new compliance measures even though underreporting of pass-through income constitutes the largest source of the tax gap.

The long history of racialized panic over “welfare fraud” may also contribute to the disproportionate attention that returns with EITC claims receive. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, lawmakers began to single out the EITC (as well as the refundable portion of the Child Tax Credit) as “welfare,” setting it apart from other benefits delivered through the tax code like the mortgage interest deduction and college savings plans, which go overwhelmingly to higher-income and disproportionately white households. A wide literature demonstrates that many politicians and interest groups have used labels like “welfare” as racist dog whistles to stoke racial animus against people of color, particularly Black Americans. Research shows that these biases persist and strongly affect how the public and lawmakers view participants in income support programs.

V. The IRS Can Be Rebuilt

Rebuilding the IRS’ enforcement division and upgrading its outdated computer systems are essential to reduce the tax gap, and these efforts would be even more effective if policymakers supplement them with specific legislative and regulatory measures aimed at narrowing the gap. These efforts should include more regular and accurate reporting of the tax gap, clear and concrete goal setting — bolstered by an iterative legislative and regulatory process to track progress — and new regulatory authorities that allow the Treasury Department to gather the information from taxpayers it needs to enforce the tax code.