BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Tax Day, which comes about a month later than usual this year, is an opportunity to take a close look at how tax and spending choices made in state capitals affect people’s lives. Smart tax and spending policies can improve family well-being, foster more vibrant local communities, and help states build more prosperous and equitable economies for all.

This year, perhaps more than most, policymakers at all levels face monumental fiscal choices whose impact — whether for good or for ill — could linger for decades. States are still wrestling with the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic and fiscal crisis, but the recent enactment of the American Rescue Plan has given states and localities a historic chance to make transformative investments in their people.

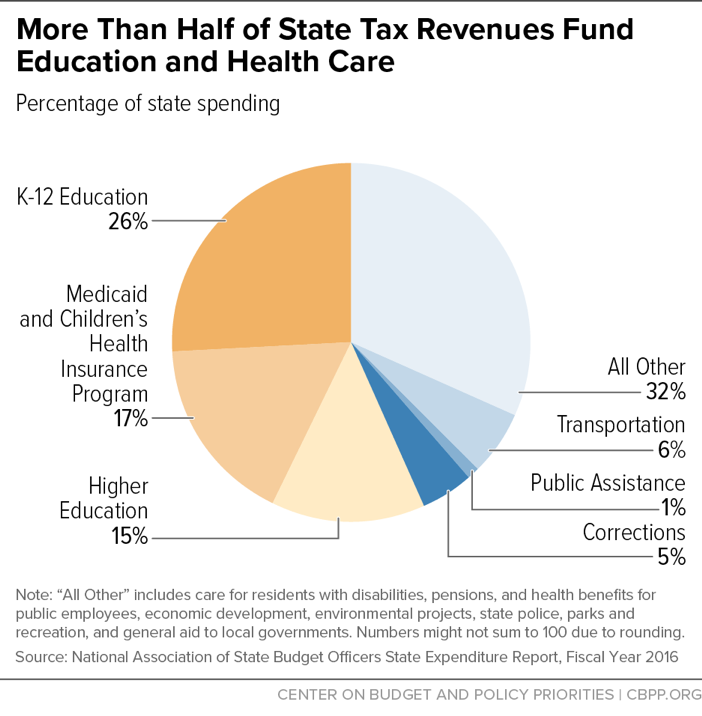

First, it’s important to understand the kinds of services and community assets that state taxes undergird: as the first chart shows, more than half of state tax dollars support education (K-12 and higher education) and health care, especially Medicaid (which is vital in normal times and is playing an important role in helping combat COVID-19). Targeted education investments can help young people and the economy reach their full potential, and they’re especially important after a decade of disinvestment in both K-12 schools and colleges and universities. State tax dollars also fund services that help nurture children, provide care for seniors and residents with disabilities, support front-line needs such as public safety and public health systems, and buttress core infrastructure including roads, transit, and water quality systems.

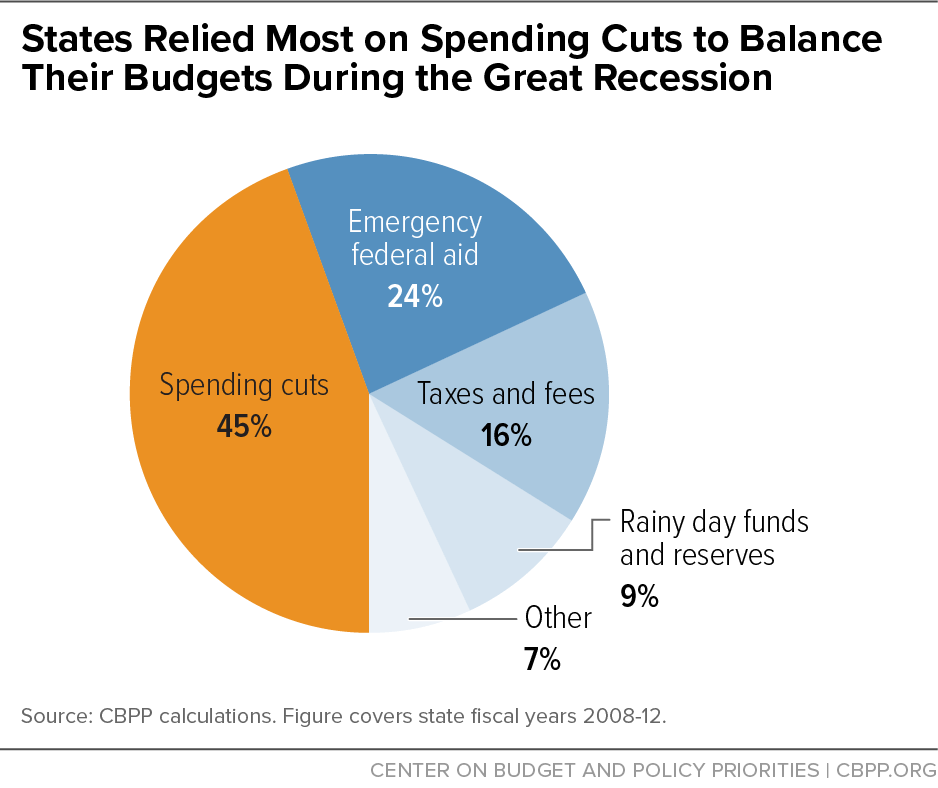

However, in the aftermath of the last economic crisis, the Great Recession of a decade ago, many states undermined these essential services by cutting taxes sharply, especially for high-income people and corporations. Partly as a result, many states exacerbated the harmful effects of the recession — and weakened the economic recovery out of the gate — by relying disproportionately on spending cuts to compensate for falling revenues (see next chart). That approach inflicted lasting damage on schools, health and economic support programs, and other public investments that are especially crucial to low-income families and people of color, and which also strengthen opportunity and help communities thrive.

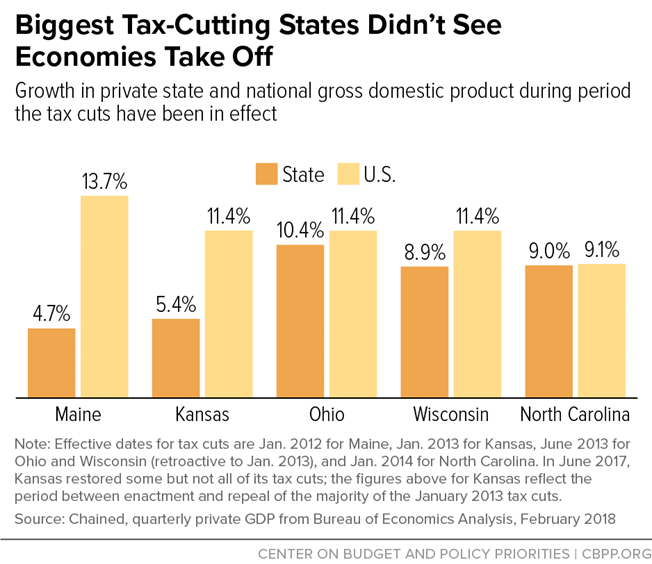

Recently, many states have followed that faulty path by considering deep, harmful tax cuts, often to personal and corporate income taxes, in many cases sold under the idea they’ll help states attract new residents or improve their economies. But such plans are as likely to harm state economies as to help them, past experience and expert research show (see next chart), and are counterproductive to racial equity as well.

During the past few months, Mississippi and West Virginia came perilously close to eliminating their personal income taxes. Several other states — including Idaho, Kansas, and Montana — have either enacted cuts or are actively considering them. And in Arizona, anti-tax lawmakers have advanced several proposals to slash personal income tax rates or exempt some taxpayers from the state’s new high-income surcharge, which voters approved in November in a big win for tax fairness and quality schools.

A better approach would be for states to raise adequate revenues, especially from affluent households and corporations that have done well in the pandemic, to avoid harmful cuts and make antiracist investments in their futures. Strengthening revenue systems is a good way to promote prosperity and equity in normal times. It’s especially crucial now so that states (and localities) can sustain the types of new investments likely to stem from the American Rescue Plan, and more generally so that they can mitigate hardship from the crisis and build more prosperous, equitable communities and economies over time.

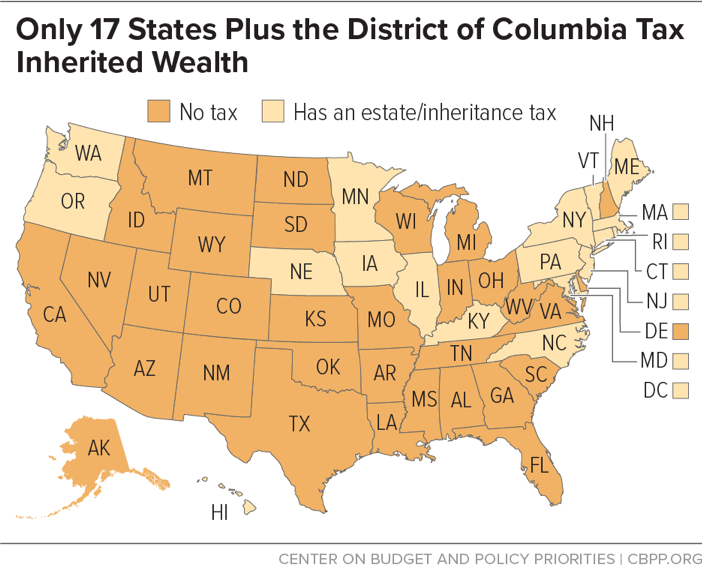

States looking to do so have a range of options, including enacting targeted tax increases on people with high incomes and closing wasteful corporate tax loopholes. States can also raise more revenue from the very wealthy, who have reaped the lion’s share of economic gains over recent decades and also weathered the COVID-19 recession comparatively well. Viable options for states to more effectively tax wealth include “mansion taxes” on expensive homes, improving taxation of capital gains (the income that investors receive when a financial asset is sold for profit), and recommitting to taxing inherited wealth in a fair way. As of October 2020, only 17 states and the District of Columbia levy either an estate or an inheritance tax (see next chart), whereas all states did 20 years ago.

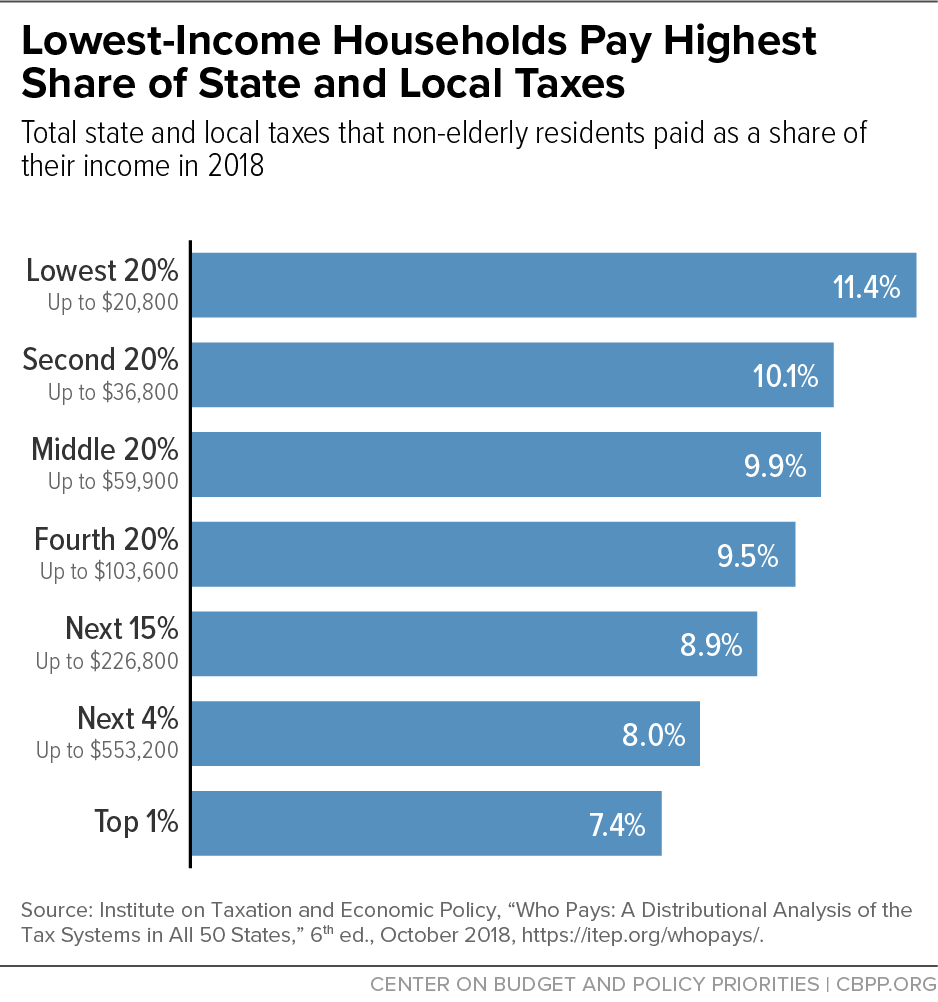

Forward-looking tax policies, such as targeted tax hikes at the top and targeted tax credits for families, can also make state and local tax systems fairer. In 9 of every 10 states, families earning the least — disproportionately families of color — pay a larger share of their income in state and local taxes than do higher-income families (see next chart). That means most state tax codes contribute to squeezing families between inadequate wages and increasingly expensive basic needs, while also requiring them to shoulder more of the load for roads, schools, health care, and other public needs.

As states like New Mexico and New Jersey have shown, targeted tax increases can help balance out state tax codes by requiring a fairer share from those at the top, while also generating needed funds to pay for investments that bolster people and communities further down the economic scale. States can also adopt or expand refundable tax credits such as the state earned income tax credit, to boost take-home pay for families paid low wages and to help address imbalances in the tax system.

Lastly, state (and local) tax policies play an important role in the fight for racial justice. This past year, COVID-19 has underscored the many ways in which racism is embedded in our nation’s health, social, and economic systems, and the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among others, have focused the nation’s attention on racial injustice more so than in the past. State tax-writers have an important role to play in moving the country toward a better place. That’s because tax policy is not race neutral: even though states do not raise revenue or collect taxes based on people’s race, historical racism and ongoing forms of discrimination and bias are tightly linked to tax policy because they shape people’s incomes and the property they own.

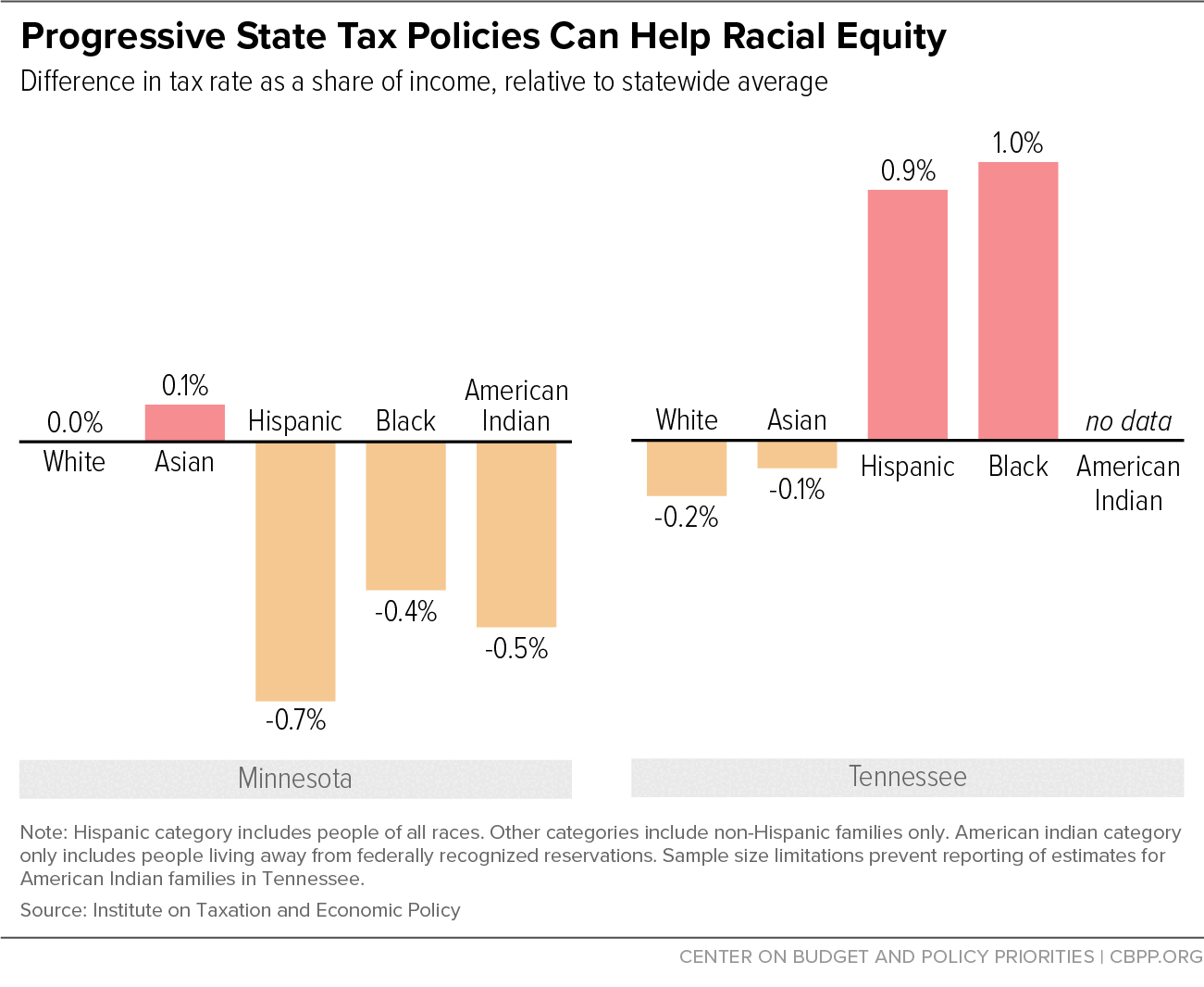

Many states and localities make existing income disparities even worse for communities of color by relying too much on regressive forms of revenue like consumption taxes or various fees and too little on income and wealth taxes, which ask more of those at the top, a group that’s disproportionately white. One case study from a recent Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) report shows the point: in Minnesota, which raises significant revenue through a progressive personal income tax, Hispanic, American Indian, and Black families pay tax rates that are 0.7, 0.5, and 0.4 percent below the state average, respectively, because their incomes are lower than the average in the state. Meanwhile in Tennessee, which raises most of its revenue through a regressive and high general sales tax (including a sales tax on food), Hispanic and Black families pay tax rates that are 0.9 and 1 percent above the state average, respectively (see final chart).